Chinese clothing

This article may be a rough translation from Chinese. It may have been generated, in whole or in part, by a computer or by a translator without dual proficiency. (April 2024) |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (April 2024) |

Chinese clothing includes the traditional hanfu and garments of ethnic minorities, as well as modern variations of indigenous Chinese dresses. Chinese clothing has been shaped through its dynastic traditions, as well as through foreign influences.[1] Chinese clothing showcases the traditional fashion sensibilities of Chinese culture traditions and forms one of the major cultural facets of Chinese civilization.[2]

Origin[edit]

Ancient Chinese literature traditionally credits the invention of clothing to legendary emperors such as Huangdi, Yao, Shun, or Youchao. In primitive societies, clothing was used to symbolize authority and specific identities. For example, as stated in the Book of Changes, Emperor Yao and Shun hung his clothes and ruled the world. The style of their clothing must be different from that of ordinary people. In addition, during military activities or ceremonial rites, the costumes of the host and participants were also different from usual. These laid the foundation for the occurrence and development of the clothing system.[3]

From the perspective of unearthed cultural relics, the origin of clothing history can be traced back to the late Paleolithic period. In ancient times, shoes were often made of animal skin, so the name of the shoe was often referred to as leather. The earliest shoe styles were very rudimentary. It has been speculated that ancient people cut animal skins into rough foot shapes and connected them with thin leather strips to form the most primitive shoes.[4]

Mountain Top Cave Man[edit]

About 19,000 years ago, one bone needle and 141 drilled stone, bone, shell, and tooth decorations were found. It was confirmed that natural materials such as animal skins could be used to sew simple clothes at that time. The history of Chinese clothing culture began from this. Seven small stone beads and 125 perforated animal teeth and other decorations were seen in the mountaintop cave, with long-term wear and tear marks on them. Among them, 5 pieces were unearthed in a semi-circular arrangement, possibly as strings of decorations. Another 25 pieces were also dyed with hematite powder, and the bones buried in the lower chamber of the mountaintop cave were also scattered with hematite powder particles, which may have been used for coloring clothes or as a finishing ceremony, reflecting a certain aesthetic sentiment of the mountaintop cave people. Protecting life, concealing oneself from the cold, and decorating oneself have all become the main functions of clothing in primitive society.[5]

The Neolithic Age[edit]

By the Neolithic period, spinning wheels became popular.[citation needed] The Yuyao Hemudu site also unearthed a "waist loom", with a cylindrical back loop that could form a natural weaving mouth, as well as a sheng (scroll). With the invention of textile technology, clothing materials became artificially woven fabrics, and silk production also began in the Neolithic Age. The form of clothing has changed and its functions have also been improved. Cloak style clothing such as headscarves and drapes soon became typical attire, with increasingly complex accessories that have had a significant impact on the formation of clothing systems.[citation needed] After the emergence of textiles, headscarves have developed into a standardized clothing style, widely used in a considerable period of time, in vast regions, and among many ethnic groups. They have basically replaced the clothing components of the Paleolithic era and become the coarse form of human clothing. In addition to general clothing, the Neolithic period also discovered crowns, boots, headgear, and accessories from some pottery relics.[6]

Shang dynasty[edit]

The main materials for clothing in the Shang Dynasty were leather, leather, silk, and linen. Due to the advancement of textile technology, silk and linen fabrics have taken an important position. During the Shang Dynasty, people were already able to finely weave extremely thin silk, jacquard geometric patterns of brocade and silk, as well as the ribbed yarn of the warp loom. The fabric is thick and heavy in color.[7]

Western Zhou Dynasty[edit]

During the Western Zhou Dynasty, the hierarchical system was gradually established, and the Zhou Dynasty established official positions such as "Si Fu" and "Nei Si Fu", which were in charge of royal attire. According to literature records and analysis of unearthed cultural relics, the Chinese coronal and attire system was initially established during the Xia and Shang dynasties and had been fully perfected by the Zhou dynasty. It was incorporated into the rule of etiquette during the Spring and Autumn period and the Warring States period. To express nobility and dignity, royal officials in different ceremonial occasions should have their crowns arranged in an orderly manner, and their clothing should also adopt different forms, colors, and patterns. From the human shaped cultural relics unearthed during the Zhou Dynasty, it can be seen that although the decoration of clothing is complex and simple, the upper and lower garments are already distinct, laying the foundation for the basic form of Chinese clothing.[8]

Imperial China[edit]

Civil and military officials[edit]

Qin dynasty (221 BC −207 BC)[edit]

Women's clothing[edit]

In the Han Dynasty, women's clothing also showed a trend of diversification, with the most famous being the "Liuxian skirt". According to the "Miscellaneous Records of the Western Capital", Zhao Feiyan was granted the title of Empress at that time, and her sister sent people to weave upper and lower jackets, forming a magnificent set of clothing. Zhao Feiyan once wore the "Yunying Purple Skirt", also known as the "Liuxian Skirt", which was a tribute from South Vietnam. This kind of skirt is similar to the pleated skirt of today and is very gorgeous.[10]

Three Kingdoms (220–280)[edit]

Women's clothing[edit]

During the Three Kingdoms period, women's clothing also had unique characteristics, reflecting the aesthetic concepts and cultural styles of that time.

A skirt or robe is one of the common attire for women. This type of dress is mostly long, with a wide hem, creating a dignified and generous atmosphere. The cuffs and stitching of the dress often carry exquisite embroidery, which may be floral, bird and animal, or other auspicious patterns, reflecting women's pursuit of beauty and love for life.

In addition, women also enjoy wearing various hair and headgear to showcase their beauty and elegance. Common hair accessories include hair combs, hairpins, hairpins, etc. These hair accessories are usually made of precious materials such as gold, silver, jade, etc., which may be inlaid with precious gemstones or jewelry, adding charm and charm to women.[11]

Sui and Tang costumes[edit]

Sui and Tang women are easy to dress up. The "half-arm" that spread from the court lasted for a long time, and later men also wore it. At that time, long towels were also popular. They were made of tusa with silver flowers painted with silver or gold and silver powder. One end was fixed on the chest strap of the half arm, and then put on the shoulder, and swired between the arms, called silk. There are various kinds of women's hair accessories in the Tang Dynasty, each with its own name. Women's shoes are generally floral shoes, mostly made of brocade fabrics, coloured silk and leather.[12]

Song style official uniform[edit]

During the Song Dynasty, there were roughly three types of Hanfu: official attire, casual attire, and traditional attire. In the Song Dynasty, the fabric of official uniforms was mainly made of silk. Due to the old system of the Five Dynasties, the government would give brocade robes to high-ranking ministers every year, divided into seven different colors such as Song Dynasty Lingjiu ball patterned brocade robes. The color of official attire follows the Tang system, with purple attire for third grade and above, red attire for fifth grade and above, green attire for seventh grade and above, and green attire for ninth grade and above. The official attire style is roughly similar to the long sleeved robe of the late Tang Dynasty, but the first attire (such as the crown hat) is already a flat winged black gauze hat, called the straight footed fu head, which is a custom attire for rulers and officials. The official attire of the Song Dynasty followed the fish wearing system of the Tang Dynasty. Officials eligible to wear purple and crimson uniforms were required to wear a "fish bag" around their waist, which contained fish made of gold, silver, and copper to distinguish their official rank. The square and curved collar is also a characteristic of the court attire, which is the decoration of the lower part of the circle placed between the neckline of the court attire. The daily casual wear of officials in the Song Dynasty, apart from their official uniforms and uniforms, mainly consisted of small sleeved round necked shirts and soft winged buns with drooping headbands, still in Tang style, but with more convenient casual shoes for daily living. The representative clothing of the Song Dynasty's elderly is a wide sleeved robe with a cross necked (cross necked) collar and a Dongpo scarf. The robe is made of dark material with edges to preserve ancient style. The Dongpo scarf is a square tube shaped high scarf, which is said to have been created by the great literary scholar Su Dongpo. It is actually a revival of ancient cloth scarves, which were often worn by the elderly gentry of the Ming.[13]

Song Dynasty Lingjiu Ball Pattern Brocade Robe[edit]

There were also various popular folk costumes in the Song Dynasty. Men are popular with futou and drapes, while women are popular with flower crowns and caps. Women's hairstyles and flower crowns were the focus of their pursuit of beauty at that time, best reflecting the changes in attire during the Song Dynasty. During the Tang and Five Dynasties, female corollas became increasingly delicate, while during the Song Dynasty, corollas underwent further development and changes. Usually, flower and bird shaped hairpins and combs were inserted into hair buns, making everything unusual.[14]

Ming Dynasty[edit]

Ming style official uniform[edit]

After the rule of the Mongols in the Yuan Dynasty, the Han tradition was restored in the Ming Dynasty, and Ming Taizu Zhu Yuanzhang re established the Hanfu clothing system. The Ming Dynasty emperor wore a black veil folded over a scarf (with black veil wings and a crown), and the hat wings stood up from the back. In the early Ming Dynasty, it was requested to restore the Tang style of clothing and headgear. The style of the legal attire was similar to that of the Tang Dynasty, except that the imperial crown for advancing talents was changed to a Liang crown, and the crown styles such as the Zhongjing crown were added. Since the Tang and Song dynasties, dragon robes and yellow have been exclusively used by the royal family. Since the Southern and Northern Dynasties, purple has been considered expensive for official uniforms. In the Ming Dynasty, due to the emperor's surname Zhu, Zhu was chosen as the official color. Additionally, due to the mention in the Analects of Confucius that "evil purple is the way to seize Zhu," purple was abolished from official attire. In the Ming Dynasty, public uniforms were also made of Futou and round necked robes, but at this time, Futou was painted with black paint on the outside, with short and wide feet, and was called Wusha hat. Non official civilians were not allowed to wear it. The most distinctive feature of public uniforms is to use "patches" to indicate the grade, in addition to the color according to the grade regulations. A patch is a piece of silk material approximately 40–50 centimeters square, woven and embroidered with different patterns, and then sewn onto official clothing, with one on the chest and one on the back. Civil officials use birds as their complement, while military officials use beasts, each divided into nine levels. To commend the achievements of officials, clothing such as python robes, flying fish uniforms, and bullfighting uniforms are specially given. The python is a four clawed dragon, the flying fish is a python with fins on its tail, and the bullfighter adds curved horns to the python's head. When reaching the highest rank, jade belts are used. So the "python robe and jade belt" became the most prominent attire of high-ranking officials at this time. Ordinary round necked robes are distinguished by the length of the clothes and the size of the sleeves, with the older ones being respected. The wives and mothers of officials who were granted official titles also wore red long sleeved dresses and various types of Xia Pi, which were differentiated by patterns and decorations. In addition, high-heeled shoes are already worn by upper class women, and there are two types of shoes: inner high sole and outer high sole. The clothing of both upper and lower levels of society has obvious levels.[15]

Cultural Protection[edit]

In the field of cultural preservation, recent research has highlighted the effectiveness of modern digital technologies, such as CLO3D, in recreating traditional Chinese clothing from the Ming Dynasty. This innovative approach allows for precise modeling of fabric texture, color, and garment structure, providing a valuable tool for historians and cultural preservationists[16] (Yang et al., 2021). These developments are significant as they offer new methods for accurately preserving and understanding historical garments, which were previously reliant on traditional replication techniques. This intersection of technology and historical study presents an exciting advancement in the conservation of cultural heritage, making it an important addition to related Wikipedia pages.[17]

Early People's Republic[edit]

Early in the People's Republic, Mao Zedong inspired Chinese fashion with his own variant of the Zhongshan suit, which would be known to the west as Mao suit. Meanwhile, Sun Yat-sen's widow, Soong Ching-ling, popularized the cheongsam as the standard female dress. At the same time, clothing viewed as backward and unmodern by both the Chinese as well as Westerners, was forbidden.

Around the Destruction of the "Four Olds" period in 1964, almost anything seen as part of traditional Chinese culture would lead to problems with the Communist Red Guards. Items that attracted dangerous attention if caught in the public included jeans, high heels, Western-style coats, ties, jewelry, cheongsams, and long hair.[18] These items were regarded as symbols of bourgeois lifestyle, which represented wealth. Citizens had to avoid them or suffer serious consequences such as torture or beatings by the guards.[18] A number of these items were thrown into the streets to embarrass the citizens.[19]

Modern fashion[edit]

Hong Kong clothing brand Shanghai Tang's design concept is inspired by historical Chinese clothing. It set out to rejuvenate Chinese fashion of the 1920s and 30s, in bright colors and with a modern twist.[20][21] Other Chinese luxury brands include NE Tiger,[22] Guo Pei,[23] and Laurence Xu.[24]

In the year 2000, dudou-inspired blouses appeared in the summer collections of Versace and Miu Miu, leading to its adoption within China as a revealing form of outerwear.

For the 2012 Hong Kong Sevens tournament, sportswear brand Kukri Sports teamed up with Hong Kong lifestyle retail store G.O.D. to produce merchandising, which included traditional Chinese jackets and cheongsam-inspired ladies polo shirts.[25][26][27]

In recent years, renewed interest in traditional Chinese culture has led to a movement in China advocating for the revival of hanfu.[28][29][30] As an increasing number of Chinese people like and attach importance to hanfu, hanfu no longer only appears in Chinese drama as in the past. Relatedly, the guochao (Chinese: 国潮; pinyin: Guó cháo) movement has resulted in younger Chinese shoppers preferring homegrown designers which incorporate aspects of Chinese history and culture, such as Shushu/Tong.[31]

It has been suggested that the most copied Chinese fashion of the 20th century is the Mao suit Zhongshan suit (simplified Chinese: 中山装; traditional Chinese: 中山裝; pinyin: Zhōngshān zhuāng) after the republican leader Sun Yat-sen (Sun Zhongshan). [32] An unexpected influence on the suit came from the north — the Soviet Union. [33]

Amongst the famous and popular who have adopted the suit is Kim Jong Un of North Korea.[34] Vietnamese leader Hồ Chí Minh is also known for wearing the Zhongshan suit. He had spent the 1920s polemicizing in communist circles in the Whampoa Military Academy, before fleeing to Hong Kong after the Nationalist purge of April 1927.[35] As much as the Zhongshan suit represented leftist utopianism, it was also used to fixate the dystopian fears of western audiences. During this time, the suit also came into the spotlight in Cold War spy films and subsequent satires. These films often depicted supervillains in Zhongshan-inspired suits. Examples include Ernst Stavro Blofeld in the James Bond franchise and Dr Evil in the Austin Powers series.

Gallery[edit]

-

Emperor Wu of Jìn, by Yan Liben (600–673)

-

Tang dynasty court ladies from the tomb of Princess Yongtai in the Qianling Mausoleum, near Xi'an in Shaanxi

-

Official Song dynasty portrait painting of Empress Cao, wife of Emperor Renzong of Song

-

Modern reconstruction of temple mural shows clothes of the Yuan dynasty

-

Ming dynasty Empress Xiao'an

-

A 15th-century portrait of the Ming official Jiang Shunfu. The decoration of two cranes on his chest are a mandarin square "rank badge" that indicate he was a civil official of the first rank.

-

Detail of Jiang Shunfu's rank badge

-

The Qing dynasty Qianlong Emperor in ceremonial armour on horseback

-

Illustration of Chinese accessories from Olfert Dapper (1670): Gedenkwaerdig bedryf der Nederlandsche Oost-Indische maetschappye

-

Zhou dynasty-style Chinese wedding dress

-

Chinese silver crown

-

Fengguan of the Ming dynasty empress

-

Hanfu of the Ming and Qing dynasties

-

Weimao in the Tang dynasty - Eighteen Songs of a Nomad Flute

-

Tang dynasty woman wearing a cross-collared robe

-

Hanfu in a famous Tang dynasty painting

-

Ancient Chinese who played Go

-

Portrait of a Ming dynasty female official

-

Gu Hongzhong's night revels

-

Traditional Chinese hat

-

Queen Mother of the West from a wall-painting in a Han dynasty tomb

-

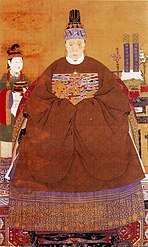

Official Ming dynasty portrait

-

Zhou Fang. Court Ladies Tuning the Lute (28x75) Nelson-Atkins Museum of Art, Kansas City (cropped)

-

Official Ming dynasty portrait

-

Cultural relics of female headdress during the Northern and Southern dynasties

-

Hat relics of Ming dynasty officials

-

Religion during the Ming dynasty

-

Famous Tang Bohu paintings

-

Hanfu during the Song dynasty

-

Portrait of a lady of the late Ming dynasty

-

Image of musicians in ancient China

-

Daily life records of court women during the Song dynasty

-

Portrait of a Ming noblewoman

-

Gu Hongzhong's Night Revels

-

Clothing relics of the Ming dynasty

-

Portrait of Li Liufang

-

Chinese bridal wedding gown

-

Traditional Chinese clothing

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Yang, Shaorong (2004). Chinese Clothing: Costumes, Adornments and Culture (Arts of China). Long River Press (published April 1, 2004). p. 3. ISBN 978-1592650194.

- ^ Brown, John (2006). China, Japan, Korea: Culture and Customs. Createspace Independent Publishing (published September 7, 2006). p. 79. ISBN 978-1419648939.

- ^ hua, mei (1999). 中国都装史 (in Chinese). Tianjin People's Fine Arts Publishing House. ISBN 9787530501627.

- ^ sima, zhen (1542). 鉴略三皇记 (in Chinese).

- ^ "Mountaintop cave man ruins". History teaching resource library.

- ^ "【灿烂的中国文明】新石器时代". Weixin Official Accounts Platform. Retrieved 2024-04-02.

- ^ "The evolution of clothing in China's dynasties". zhihu.

- ^ Zhouli [Zhouli] (in Chinese). Jinlang Academic Publishing House. 2017. p. 295. ISBN 978-3330821347.

- ^ a b Łukasz Sęk. "Chiński bucik królowej Marysieńki Sobieskiej" (in Polish). it.tarnow.pl. Retrieved 7 July 2014.

- ^ 罗, 莹 (2003). 成镜深.中国古代服饰小史 Cheng Jingshen. A short history of ancient Chinese dress (in Chinese). 四川职业技术学院学报. p. 201.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ wangyi (2023-10-18). "三国时期服饰特点 Costume characteristics of The Three Kingdoms period". www.163.com. Retrieved 2024-04-05.

- ^ Na, CHUNYING (2023). 隋唐平民服饰研究 A study on civilian dress in Sui and Tang Dynasties (in Chinese). 人民出版社. p. 33. ISBN 9787010253961.

- ^ FU, BOXING (2016). 大宋衣冠:图说宋人服饰 Dress of the Song Dynasty: A picture of Song dress (in Chinese). Shanghai Ancient Books Publishing House. p. 110. ISBN 978-7-5325-7765-1.

- ^ zuo, qiumeng (2024). 中国妆束:宋时天气宋时衣 Chinese makeup bundle: Song Dynasty weather Song dynasty clothes (in Chinese). qinghua university. p. 144. ISBN 9787302640820.

- ^ Mingjian [Mingjian] (in Chinese) (1 ed.). China: China Textile press and apparel press. 2021. p. 154. ISBN 978-7518083428.

- ^ Yang, Shuran; Yue, Li; Wang, Xiaogang (August 2021). "Study on the structure and virtual model of "xiezhi" gown in Ming dynasty". Journal of Physics: Conference Series. 1986 (1): 012116. Bibcode:2021JPhCS1986a2116Y. doi:10.1088/1742-6596/1986/1/012116. ISSN 1742-6596.

- ^ gu, xiaosi (2022). 华夏衣橱 (in Chinese). Electronics Industry Press. ISBN 9787121443657.

- ^ a b Law, Kam-yee. [2003] (2003). The Chinese Cultural Revolution Reconsidered: beyond purge and Holocaust. ISBN 0-333-73835-7

- ^ Wen, Chihua. Madsen, Richard P. [1995] (1995). The Red Mirror: Children of China's Cultural Revolution. Westview Press. ISBN 0-8133-2488-2

- ^ Broun, Samantha (6 April 2006). "Designing a global brand". CNN World. Archived from the original on 26 October 2012. Retrieved 2 June 2012.

- ^ Chevalier, Michel (2012). Luxury Brand Management. Singapore: John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-118-17176-9.

- ^ 1 Archived 2014-01-10 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ 1.

- ^ "China's Hainan Airlines: Coolest cabin crew uniforms ever?". CNN World. 14 July 2017. Retrieved 14 July 2017.

- ^ "G.O.D. and Kukri Design Collaborate for the Rugby Sevens". Hong Kong Tatler. 16 March 2012. Archived from the original on 15 August 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "G.O.D. x Kukri". G.O.D. official website. Archived from the original on 15 May 2012. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ "Kukri and G.O.D. collaborate on HK7s Range!". Kukri Sports. Archived from the original on 2 February 2014. Retrieved 19 November 2012.

- ^ Bullock, Olivia (November 13, 2014). "Hanfu Movement Brings Back Traditional Fashion". The World of Chinese. Archived from the original on January 27, 2020. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ^ Wee, Teo Cheng (November 20, 2015). "Stepping back in time at China's schools for traditional culture and Confucianism". The Straits Times. Retrieved July 30, 2016.

- ^ Zhou, Dongxu (June 18, 2015). "China Prepares 'Traditional Culture' Textbooks for Its Officials". Retrieved July 30, 2016 – via Caixin.

- ^ Nan, Lisa (2021-07-07). "Can Shushu/Tong Go Global?". Jing Daily. Retrieved 2024-05-09.

- ^ "Evolution and revolution: Chinese dress 1700s-1990s - Mao suit". archive.maas.museum. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ MrOldMajor (2022-05-13). "The Zhongshan suit". Medium. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ Moore, Booth (2018-06-12). "The Summit May Have Been Historic, But Kim Jong Un's Mao Suit Was Business as Usual". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

- ^ MrOldMajor (2022-05-13). "The Zhongshan suit". Medium. Retrieved 2024-06-04.

Further reading[edit]

- Watt, James C.Y.; Wardwell, Anne E. (1997). When silk was gold: Central Asian and Chinese textiles. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 0870998250.

- Jian, Li; Li, He & Sung, Hou-Mei & Shengnan, Ma (2014). Forbidden City: Imperial Treasures from the Palace Museum, Beijing. Richmond, Virginia: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts. ISBN 978-1-934351-06-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)