20th century in ichnology

The 20th century in ichnology refers to advances made between the years 1900 and 1999 in the scientific study of trace fossils, the preserved record of the behavior and physiological processes of ancient life forms, especially fossil footprints. Significant fossil trackway discoveries began almost immediately after the start of the 20th century with the 1900 discovery at Ipolytarnoc, Hungary of a wide variety of bird and mammal footprints left behind during the early Miocene.[1] Not long after, fossil Iguanodon footprints were discovered in Sussex, England, a discovery that probably served as the inspiration for Sir Arthur Conan Doyle's The Lost World.[2]

Several enduring mysteries from the 19th century continued to vex ichnologists, like the identity of the Chirotherium trackmaker. Renowned paleontologist Franz von Nopcsa attributed the ichnogenus to the prosauropod dinosaur Plateosaurus, despite an apparent mismatch between its number of toes (4) and the preserved digit traces of Chirotherium (5). Von Nopcsa explained the discrepancy by arguing that one of the impressions in the Chirotherium tracks was left by a soft tissue structure that did not fossilize.[3] However, it was Wolfgang Soergel who correctly hypothesized that Chirotherium was produced by a distant relative of modern crocodilians. Using only its footprints as a guide he reconstructed the life appearance of the Chirotherium trackmaker. Decades later paleontologists described an animal named Ticinosuchus which precisely fulfilled Soergel's predictions. Ticinosuchus or a close relative seems to have been the true Chirotherium trackmaker.[4]

During the 20th century, many significant fossil trackway discoveries were made in the western United States. In the 1930s and 1940s, Roland T. Bird discovered the tracks of large sauropod and theropod dinosaurs in Texas. He excavated a major section of the track ways on behalf of the American Museum of Natural History. This was the first large scale excavation of fossil footprints in history.[5] In the 1950s Lee Stokes reported unusual footprints he interpreted as the first known pterosaur tracks.[6] This attribution would be controversial much of the rest of the century but has since been vindicated.[7] The dinosaur footprints of Dinosaur Ridge in Colorado were also discovered and studied in the 20th century.[8]

The advent of the dinosaur renaissance and the publication by R. McNeil Alexander of a formula which could reconstruct their running speed based on data from fossil trackways brought renewed interest and prestige to ichnology during the late 20th century.[9] This led to several symposia on the subject of vertebrate trace fossils. In 1986 such a conference dedicated to dinosaur footprints was held in New Mexico.[10] Roughly a decade later renowned German ichnologist Heinrich Haubold organized a conference dedicated to the more ancient footprints of the Paleozoic Era. This gathering has been regarded as a turning point in the study of tracks of that age.[11]

1900s[edit]

- A major Lower Miocene fossil footprint site was discovered at Ipolytarnoc, Hungary. The site preserves more than 1600 individual footprints from a variety of birds and mammals. Avian ichnogenera at the site include Aviadactyla, Ornithotarnocia, Passeripeda and Tetraornithopedia. Mammalian ichnogenera include Bestiopeda, Carnivoripeda, Megapecoripeda, Mustelipeda, Pecoripeda, Rhinoceripeda. These mammal tracks were left by creatures like carnivorans, peccaries and rhinoceros. Mastodon tracks have also been reported, but may represent misidentifications.[1]

- Dinosaur footprints were discovered at Fisher's Quarry, near Graterford, Pennsylvania. These tracks are now classified in the ichnogenus Atreipus.[12]

- John Bell Hatcher reported probable crocodilian footprints from the Morrison Formation near Canon City, Colorado.[13]

- Richard Swann Lull began studying the Connecticut Valley footprints.[14] He described the new ichnogenus Anchisauripus, named such because he attributed it to the early sauropod-precursor Anchisaurus.[15]

- Luis Dollo matched the foot of Iguanodon bernissartensis with a purported Iguanodon footprint in "the first attempt to match these tracks with a particular species of the genus".[16]

- Pleistocene human footprints were discovered in the Niaux cave complex of France.[17]

- Paleocene fossil amphibian footprints were discovered in the Fort Union Formation of Montana.[18]

- Harold Broderick described the three-toed Middle Jurassic dinosaur footprints that had first been discovered during the 1890s at England's Yorkshire coast.[19]

- Fossil Iguanodon footprints were discovered in the rocks of the Wealden Beds at Crowborough, Sussex. These tracks may have inspired Sir Arthur Conan Doyle to write The Lost World.[2]

1910s[edit]

- Traces in the genus Octopodichnus were discovered in the Permian Lyons Sandstone of Colorado.[20]

- Joviano Pacheco discovered the first dinosaur footprints in Brazil.[21]

c. 1914

- 90 million year old Cretaceous dinosaur footprints were discovered in New Jersey but were accidentally destroyed during an attempt at excavating them.[12]

- Barnum Brown discovered the Centrosaurus apertus specimen AMNH 5351. Randy Moore has described the skeleton as the most complete Brown ever discovered.[22]

- Charles Schuchert discovered Carboniferous-aged fossil footprints in the rocks of the Wescogame Formation near the Grand Canyon.[23]

1920s[edit]

- Charles Whitney Gilmore began collecting and studying the Carboniferous and Permian-aged footprint fossils of the Grand Canyon area on behalf of the Smithsonian. He also constructed an outdoor exhibit about the tracks at Hermit Trail.[23]

- William Peterson reported the discovery of large three-toed dinosaur tracks preserved in what is now the ceiling of a Carbon County, Utah coal mine. William Diller Matthew attributed these tracks to tyrannosaurs.[26]

c. 1920

- Renovations to Oak Hill, the historical home of US President James Monroe, led to the discovery of fossil dinosaur footprints when workers repaved the properties walkways with Lower Jurassic stone. The preserved tracks included Grallator and Eubrontes prints ranging in length from 13 to 33 cm (5 to 13 in).[12] Other local footprints included the tracks of a crocodilian-like animal, Batrachopus. The tracks originated in the Midland Formation.[27]

- Baron Franz von Nopsca published a "seminal" work on fossil amphibian and reptile tracks.[3] He hypothesized that Plateosaurus was the Chirotherium trackmaker. Although Plateosaurus has only four hind toes and Chirotherium tracks have five impressions, Nopsca followed Willruth's argument that the "thumb" of Chirotherium was composed only of soft tissue and would have left no skeletal record.[28] He also named the large Late Jurassic theropod fossils discovered at Cabo Mondego, Portugal Eutynichnium lusitanicum. However, this name lacks validity because Nopsca did not formally describe it or designate a type specimen.~154~

- J. Henderson reported the first known Paleozoic footprint fossils from Colorado.[29]

- Wolfgang Soergel interpreted the Chirotherium trackmaker as a pseudosuchian related to, but much larger than, Euparkeria.[28] He noted that the bulk of the animal's weight was born by its hindlimbs.[30]

- German geologist Adolf Bachofen-Echt reported the first scientifically recognized dinosaur tracks from Croatia. These three-toed tracks were preserved on the Brioni Islands and Bachofen-Echt thought they were made by Iguanodon.~218~

- Charles Whitney Gilmore published his first report on fossil footprints from the Grand Canyon area.[29]

- Comte Begouen reported the presence of an adult human's tracks in the Grotte de Cabarets cave in France. These tracks are accompanied by impressions left by the human's walking stick.[31]

- Charles Gilmore described the Paleocene amphibian tracks from the Fort Union Formation of Montana. He named the new ichnospecies Ammobatrachus montanensis for the tracks. He observed that these were the first Paleocene fossil footprints to be documented in the scientific literature.[18]

- Potential Paleocene mammal footprints were reported from Alberta.[18]

- Hernandez-Pacheco described an Oligocene-aged fossil bird track site at Peralta de la Sal, Spain.[32]

- 90 million year old Cretaceous carnivorous dinosaur footprints were discovered at the Hampton Cutter Clay Works quarry at Woodbridge, New Jersey.[12]

- Teilhard de Chardin and C. C. Young reported the discovery of dinosaur footprints in Shanxi Province, China. These were the first scientifically documented dinosaur footprints in the country's history.[33]

1930s[edit]

- Bradford Willard discovered a new ichnogenus Devonian-aged trace fossils in Pennsylvania that he named Paramphibius because he thought the trackmaker was a transitional form between fishes and tetrapods. He named a new taxon, the Ichthyopoda to classify this creature.[34]

- Permian-aged fossil footprints were reported from the Abo Formation near Las Cruces, New Mexico.[35]

- The University of Michigan Museum of Paleontology bought several slabs of Late Triassic fossil footprints collected near Mesa Redonda, New Mexico. Among the preserved tracks were three-toed reptile footprints and the four-toed ichnogenus Pseudotetrasauropus that may have been left by a primitive sauropodomorph.[36]

- Roland T. Bird discovered a new Early Jurassic dinosaur tracksite in the Moenave Formation of northwestern Arizona. Although the site's location would be lost, Bird's photographs would help Dinosaur National Monument paleontologist Scott Madsen, and friend Keith Becker, relocate the site decades later.[37]

- Dinosaur tracks were excavated from the Dakota Group near Lamar, Colorado. These tracks are now exhibited by the Denver Museum of Natural History.[38]

- Late: An expansion of the Nevada State Prison was built over the Pleistocene fossil footprints that had been discovered there. However, some specimens had been collected before and are now curated by the Nevada State Museum.[39]

- Fredrick von Huene reported the presence of Early Jurassic fossil footprints that were probably left by an evolutionary precursor to mammals in the Botucatu Sandstone of Brazil.[6]

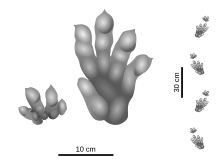

- Maurice Mehl erected the new ichnogenus Ignotornis for some bird tracks preserved in the Dakota Group near Golden, Colorado. These were the first scientifically documented Mesozoic bird footprints.[40] The bird in question as interpreted as a "small shorebird or wader".[41] The site would eventually be heavily collected and all of its tracks were presumed removed.[40]

- Edward Branson and Maurice Mehl reported the presence of Carboniferous-aged fossil footprints of a new ichnospecies in the Tensleep Formation of Wyoming.[23] They named the tracks Steganoposaurus belli and attributed them to an amphibian nearly three feet in length.[42]

- Edward Branson and Maurice Mehl named a new kind of Late Triassic dinosaur footprint discovered in the Popo Agie Formation of western Wyoming. The new ichnogenus and species was named Agialopus wyomingensis.[43]

- Late Triassic dinosaur footprints were discovered near Gettysburg, Pennsylvania.[44]

- Carlton S. Nash found some more dinosaur footprints near the original location of Pliny Moody's track discovery in Massachusetts.[45]

- The dinosaur footprints were reported in Australia for the first time.[46]

- Toepelman and Rodeck made the first report on fossil arthropod trackways in the Lyons Sandstone and fossil vertebrate footprints preserved in the Fountain Formation.[25]

- The Dinosaur Ridge dinosaur tracksite was discovered near Denver, Colorado. Tracks include those made by ornithopods and theropods. Some of the ornithopod tracks seem to have been left by individuals traveling together and are thus evidence for social behavior.[47] Further, these ornithopods seem to have traveled predominantly on all fours, unlike most ornithopod tracks, which were made by bipeds.[48]

- The New York Times reported that Barnum Brown had discovered the fossil footprints of a huge and unknown kind of dinosaur in a Wyoming coal mine. Brown's claim was simply a "publicity stunt" aimed at attracting funding.[49] However, Brown's report attracted the attention of a coal mine operator from the Cedaredge, Colorado area named Charlie States, who reported large dinosaur footprints spaced five meters apart in his mine, the Red Mountain Mine.[50] Brown and his assistant Roland Bird oversaw an "ambitious" excavation of the purported giant's tracks. After three weeks of 24-hour labor on the part of the miners and the development of specialized equipment to extract the specimen, a 17-foot long slab of track-bearing rock was taken from the mine and shipped to the American Museum of Natural History in New York City.[51]

- More Late Triassic dinosaur footprints were discovered near Gettysburg. These tracks ranged from chicken-sized to 15 cm (5.9 in) in length.[44]

- Elmer R. Haile Jr. collected Late Triassic reptile tracks from the Trostle Quarry near York Springs, Pennsylvania. The preserved ichnogenera included the dinosaur ichnogenus Atreipus and other reptile traces like Brachychirotherium and Rhynchosauroides.[44]

- Kenneth Caster conclusively demonstrated that unusual fossil tracks from the Solnhofen lithographic limestone variously attributed to creatures like Archaeopteryx, little dinosaurs, or pterosaurs were actually made by horseshoe crabs, as specimens had been found literally "dead in their tracks".[52] Similar fossils in the United States had been attributed to a transitional form between fishes and tetrapods by Bradford Willard earlier in the 1930s.[34]

- Roland T. Bird discovered twelve sauropod and four theropod trackways in the Early Cretaceous Glen Rose Formation of Texas.[citation needed]

- Brown published a description of the dinosaur tracks with the purported giant stride length. He tried to keep up his charade of there being an undiscovered mystery dinosaur by downplaying "the obvious hadrosaurian affinity of the tracks".~???NA220-221~

c. 1939

- Nash bought the Massachusetts property where he discovered dinosaur footprints. He would begin excavating and selling the dinosaur footprints on his land and the property would come to be known as Nash Dinosaur Land.[45]

- Lionel F. Brady began experimenting with living arthropods to help determine which sorts of arthropods may have produced various ancient trace fossils.[53]

- Sumner Anderson reported the presence of small carnivorous dinosaur footprints between 15 and 20 cm in length preserved in the Early Cretaceous Lakota Formation at two different sites in South Dakota.[54]

- Earl L. Poole of the Public Museum and Art Gallery discovered a new Late Triassic dinosaur track site at a quarry near Schwenksville, Pennsylvania.[44] The dozens of tracks preserved there were mostly left by chicken-sized dinosaurs, but about a "half dozen" of them were left by turkey-sized trackmakers.[55] Poole ascribed these tracks to the ichnogenus Anchisauripus. One footprint was left by a dinosaur with about the same body mass as a horse.[45] This site is now known as the Squirrel Hill Quarry.[44]

1940s[edit]

- Frank Peabody performed "extensive" research on Early Triassic fossil footprints.[56]

- Roland T. Bird oversaw the excavation of sauropod and theropod tracks from the Paluxy River in Texas. This was the first large-scale dinosaur track excavation in history.[57]

- Frank Peabody studied the early Pliocene fossil amphibian footprints of the Sierra Nevada Mountains of California. He found them to be almost identical to the tracks of their descendants. This was his first major contribution to ichnology.[58]

- Friedrich von Huene named the ichnogenus Coelurosaurichnus for small three-toed carnivorous dinosaur tracks discovered in northern Italy.[59]

- Bird described his experiences excavating dinosaur tracks for the American Museum of Natural History in Texas.[60]

- H. H. Nininger reported the presence of fossilized lion footprints in Arizona.[61]

- Robert Chaffee reported the presence of a tracksite from Wyoming preserving the footprints of a camel-like even-toed ungulate and a rhinoceros-like odd-toed ungulate in the Oligocene-aged White River Beds. He noted that only two other Oligocene fossil tracks were known and neither had been described.[62] Chaffee attributed one of these, a partial print preserved in the Yale Peabody Museum, to a brontothere.[63]

- Bird described the Davenport Ranch dinosaur tracksite.[60]

- F. E. Peabody argued that the "horseshoe-like" impressions reported from the Moenkopi Formation were actually "current crescents".[64]

- Norbert Casteret reported the presence of Pleistocene hyena tracks in the Aldene cave of France.[65]

- F. E. Peabody published a study of the amphibian and reptile tracks preserved in the Triassic Moenkopi Formation. Lockley and Hunt would later regard this paper as "a classic" in the field.[64]

1950s[edit]

- A rock hound named Al Look "embellished" Barnum Brown's mystery dinosaur hoax, informally naming the creature "Xosaurus". He also reported having encountered another dinosaur trackway with a similarly long stride as Brown's original specimen. This trackway supposedly recorded the huge mystery dinosaur stepping on a crocodile-like reptile.[66]

- Albert de Lapparent and others restudied the large Late Jurassic theropod tracks of Cabo Mondego.[24] They thought the tracks were made by Megalosaurus.[67]

- Henry Faul and Wayne Roberts reported the presence of Early Jurassic fossil footprints in Colorado's Navajo Sandstone. These tracks were probably left by an evolutionary precursor to mammals.[6]

- Wilhelm Bock reinterpreted the footprints discovered in the Squirrel Hill Quarry as Grallator and non-dinosaurian archosaur tracks. He also described the ichnospecies Anchisauripus gwynnedensis for a dinosaur track discovered in the North Pennsylvania Railroad tunnel near Gwynned. These tracks are now thought to belong to Atreipus, however.[45]

- Pennsylvanian-aged footprint fossils were discovered in the Minturn Formation near Dotsero, Colorado.[68]

- Lull published a "[c]lassic monograph updating the work of Edward Hitchcock."[69]

- Frank Peabody renamed Ammobatrachus montanensis Ambytomichnus montanensis due to their resemblance to the modern newt family Ambystomidae. He observed that these were the oldest known salamander footprints.[18]

- A French ichnologist named Lessertisseur erected the ichnogenus Megalosauripus. He attributed the Cabo Mondego tracks to a megalosaurid.[70] He also named the ichnogenus Tyrannosauripus, but as both ichnogenera lacked type species and type specimens these taxonomic names were invalid.[71]

- M. F. Farmer published the locations of many track sites in northern Arizona.[72]

- Albert de Lapparent and Zybyszewsky published further research on the large Late Jurassic theropod tracks of Cabo Mondego.[24]

- The new ichnospecies Limnopus cutlerensis was described from the Permian-aged Cutler Group in Colorado.[73]

- Lee Stokes erected the new ichnogenus Pteraichnus for fossil footprints discovered in the Morrison Formation of Utah that he thought were left by pterosaurs.[6]

- Curry published research on the fossil footprints of the Eocene Green River Group.[61]

- Oskar Kuhn named the new Early Cretaceous theropod ichnogenus and species Buckeburgichnus maximus from Germany. It is notable in its preservation of a large hallux impression.[74]

- Brady and Seff reported the presence of fossil mammoth footprints near Montezuma Castle National Park in Arizona.[61]

1960s[edit]

- An important Late Triassic dinosaur tracksite was discovered northeast of Dinosaur National Monument.[43]

- July 30: A team of 36 geologists set out on a field trip to Spitzbergen in preparation for the 21st International Geological Congress.[75]

- August 3rd: Albert de Lapparent and Robert Lafitte stumbled on some fossil footprints left by a large bipedal dinosaur in the Festningen Sandstone at Isfjorden, Svalbard.[76] The researchers suspected that the tracks were made by a carnosaur. At 78 degrees of latitude north, these were the highest latitude dinosaur tracks known in the world, up from the previous record of 56 degrees.[77]

- A geologist named H. D. Curry working for the Shell Oil Company discovered a slab of rock preserving high quality three-toed mammal footprints in Utah's Strawberry Canyon. The trackmakers were probably Eocene relatives of modern tapirs and horses. Curry donated the so-called "Strawberry Slab" to the Smithsonian Institution.[78]

- Albert de Lapparent reinterpreted the dinosaur tracks from Spitzbergen. Although mentioning their initial impression that the tracks were carnosaurian, he concluded that the tracks were probably left by Iguanodon instead, due to their lack of claw marks, rounded toe prints, and general similarity to the feet of Iguanodon bernissartensis.[77]

- Panin and Avram published research on Miocene fossil bird and mammal tracks from the vicinity of the Carpathian Mountains of Romania. They attributed the local bird footprints to four different families, the anatids, ardeids, charadriids, and gruids. Contemporary mammalian trackmakers included artiodactyls, cats, dogs, and relatives of modern elephants. The latter of these left behind one thoroughly trampled site with an area of more than 100 sq m. The researchers erected several new ichnotaxa for the tracks they studied and similar tracks would later be discovered elsewhere in Europe.[79]

- The first dinosaur footprints known from Israel were discovered.[80]

- Justin Delair named the new ichnogenus and species Purbeckopus pentadactylus for tracks preserved in the Purbeck Limestone of Dorset, England. He was unable to confidently identify the trackmaker, but speculated that they may be crocodilian in origin.[81]

- A large pseudosuchian named Tichinosuchus was named for remains found in Swiss Triassic rocks. It had the right size and anatomy to account for the Chirotherium tracks of Europe and is considered the most likely trackmaker.[82]

- de Raaf, Beets, and Kortenbout van der Sluijs reported the presence of a large number of well-preserved web-footed bird tracks from Oligocene rocks in Spain.[83] The high percentage of the fossil trails being oriented in the same direction suggests that this deposit records evidence for flocking in these ancient birds. This is extraordinary because evidence for social behavior in fossil bird footprints is very uncommon.[32]

- R. M. Alf described Miocene-aged fossil footprints discovered in the Mojave Desert.[61]

- The Israeli dinosaur footprints were formally described.[80]

- Two dinosaur trackways were discovered in the Roach Stone of Acton, England.

- B. R. Erickson published research on the Eocene bird tracks preserved in the Green River Group of Utah.[61]

- Raymond Alf demonstrated that tracks similar to arthropod trace fossils from the Coconino Sandstone are produced by large modern tarantulas.[53]

- Bessonat, Dughi, and Sirugue described an Oligocene bird and mammal track site at Veins, France.[84]

- March: A coal miner working near Hayden, Colorado hit his head on the natural cast of a dinosaur footprint while in pursuit of a run-away coal cart. The impact injured his spinal cord, leading to his death 10 days later.[85]

1970s[edit]

- Mid: Dinosaur tracks of the ichnogenera Atreipus and Grallator were discovered in a quarry that straddles the Virginia-North Carolina border. These may be the oldest dinosaur tracks known in the eastern United States.[86]

- Late: The publication of a formula capable of inferring the life speeds of dinosaurs from their fossil trackways brought further attention to Barnum Brown's claim of having discovered the tracks of a mystery dinosaur with an abnormally long stride length. Scientists instantly recognized the footprints as belonging to a duck-billed hadrosaur rather than some completely unknown dinosaur, but the validity of the trackway's stride length proved controversial. Dale Russell and Pierre Beland accepted Brown's measurement and calculated the trackmaker as moving at 27 kilometers an hour. Tony Thulborn argued that a footprint left by another dinosaur obscured a track left by the original trackmaker roughly halfway between the prints composing the supposedly enormous stride. This implied that the trackmaker's stride was only half the claimed size and it was probably only traveling at about 8.5 kilometers an hour.[66]

- Leonard Wills and Bill Sarjeant reported potential dinosaur footprints from Triassic rocks in Nottinghamshire and Worcestershire. Ichnotaxa reported included Coelurosaurichnus, Otozoum, and Swinertonichnus. The rocks were of uncertain age at the time of the authors writing and are now known to have been Lower Triassic.[87] Dinosaur tracks dating to the Early Triassic would be anomalous as their skeletal remains are not known until later in the period.[88] Not surprisingly, the dinosaurian status of the tracks reported by Wills and Sarjeant have been disputed.[87]

- Hartmut Haubold named the Brazilian proto-mammal tracks Tetrapodichnus.[6]

- Haubold formally named the German ichnospecies Metatetrapous valdensis from Germany's Wealden Beds. The discovery may represent fossil ankylosaur footprints.[89]

- de Clercq and Holst published on the Upper Oligocene bird tracks of Lucerne, Switzerland. The researchers attributed the tracks to rails.[90]

- Samuel Welles named two new Early Jurassic theropod ichnogenera from the Kayenta Formation of northeastern Arizona; Dilophosauripus and Kayentapus.[91] also Hopiichnus.[92]

- Vialov classified fossil bird footprints as members of the ichno order Avipedia.[93]

- David Webb studied the fossil footprints left by ancient camels and determined that even these ancient forms shared modern camels' "pacing gait", where the animal moves both legs on one side of the body at the same time, unlike most mammals which move hindlimbs and forelimbs from the opposite sides of the body in each step. Webb argued that the energetic efficiency of the pacing gait enabled camels' success in desert and prairie environments where significant distances may separate food and water sources.[94]

- Paul Olsen and Robert F. Salvia discovered dinosaur Late Triassic footprints in the Stockton Formation of Nyack Beach State Park, New York. The tracks included 12–15 cm (4.5–6 in) long Grallator tracks. Possible Atreipus tracks were also found there. The regions's non-dinosaurian tracks included Apatopus, Brachychirotherium, Chirotherium, and Rhynchosauroides.[95]

- Justin Delair and A. B. Lander reported the presence of three parallel dinosaur trackways in the Roach Stone of Herston, England.

- A significant Permian-aged fossil tracksite in the Cedar Mesa Sandstone of Utah was inundated following the creation of the Glen Canyon Dam. This tracksite preserved an apparent predator-prey interaction wherein the trail left by a small amphibian or reptile vanished at the point where it intersected with the trail left by a large carnivorous proto-mammal. Fortunately for ichnologists, plaster casts of the trackways and photographs remain available for study.[96]

- W. J. Breed reported fossil goose footprints from the Pliocene Bidahochi Formation of Arizona.[61]

- Kaever and de Lapparent named the new ichnogenus and species Elephanotpides barkhausensis for the poorly preserved tracks of a large quadrupedal dinosaur discovered near Barkhausen, Germany. The trackmaker was probably a sauropod.[97]

- Heinberg describes Ancorichnus, a non-marine burrowing animal.[98]

- A fossil footprint was discovered in the Upper Permian Val Gardena Sandstone. The track would later become known as Pachypes dolomiticus and is apparently the first pareiasaur track ever discovered.[99]

- Bill Sarjeant described the five-toed Middle Jurassic footprints discovered by C. Pooley and named it Pooleyichnus burfordensis in his honor.[100] Sarjeant proposed that this unusual track may have been made by a mammal.[101]

- A large tracksite preserved in the late Eocene Vieja Group of Texas was first studied in a University of Texas research program.

- Robert E. Weems was informed of, and began researching, a Late Triassic reptile track site in a quarry near Culpeper, Virginia.[102]

- Miguel Antunes published a cursory description of the Late Jurassic sauropod tracks of Cabo Espichel, Portugal.[103]

- Leon Pales described the Pleistocene human footprints of France's Niaux cave complex. This paper has been considered "one of the most comprehensive studies of cave footprints ever published."[17]

- R. McNeil Alexander published a formula for inferring the speeds of dinosaurs from their fossil trackways.[72]

- Russell and Beland examined Brown's claim to have discovered the tracks of a running dinosaur.[104]

- Several hundred Late Triassic dinosaur footprints were reported from the vicinity of Cardiff, Wales.[105] This report was made by M. E. Tucker and T. P. Burchette.[106]

- Terry Logue reported the presence of fossil pterosaur footprints in the Sundance Formation.[107]

- Marc Edwards and others reported the dinosaur footprints discovered in Spitzbergen in 1978. Only two footprints were discovered at the site, which was an exposure of the Helvetiafjellet Formation. The researchers interpreted the tracks as carnosaur footprints, but now they are thought to have been left by iguanodontids.[108]

- Stokes observed that tracks left by close evolutionary relatives of mammals were common and widespread in the Navajo Sandstone. He found such tracksites in Colorado, Idaho, and Utah.[109] He reported many new sites in the Navajo formation.[92]

- Ismael Ferrusquia-Villafranca and others reported the discovery of the first dinosaurs tracks to be scientifically documented in Mexico.[110]

- A 36 cm wide, 18 meter long Middle Carboniferous trackway that was apparently left by the giant millipede-like Arthropleura was reported from the Island of Arran.[111]

- Carme Lompart reported the presence of Late Cretaceous dinosaur tracks in the Ager Valley of Spain, near the country's border with France.[112]

- Marc Weidmann and Manfred Reichel published a "lengthy" review of the Oligocene to Miocene aged bird tracks found in Switzerland's "Molasse" rock.[90] They reported the presence of tracks left by one kind of duck, two kinds of herons, one kind of perching bird, and four kinds of waders.[113] Weidmann and Reichel devoted intense effort to classifying these tracks based on previous schemes devised by scholars like Avram, Panin, and Vialov for other bird track sites.[93] They also worked diligently to discern the tracks' positions within the stratigraphic column.[114]

1980s[edit]

- Mid: Dinosaur footprints were first reported from the Laramie Formation.[115]

- Paul Ellenberger reported the presence of Eocene artiodactyl and bird tracks near Garrigues, France. There were several kinds of mammals tracks, including Anoplotheripus, Diplartiopus, Hyaenodontipus, Lophiopus, Palaeotheripus, and Ucetipodisus.[116]

- A nine meter long Pleistocene bear trackway was reported from Lake County, Oregon. The tracks themselves were about 40 cm long, suggesting a trackmaker roughly the size of a large modern bear. These tracks may have been left by an Arctotherium.[117]

- Olsen argued that the ichnogenera Grallator, Anchisauripus, and Eubrontes actually represent a growth series.[69]

- R. L. Laury described fossil "tracks associated with mammoth skeletons" in Hot Springs, South Dakota.[61]

- Walter P. Coombs, Jr. interpreted some unusual Eubrontes tracks from Dinosaur State Park of Rocky Hill, Connecticut as traces left by a swimming theropod because the tracks only preserved impressions from the tips of the animal's toes as if the rest of its body weight was supported by water.[118]

- Alfred Hendricks named the ichnospecies Rotundichnus munchehagensis for some "wide-gauge" sauropod tracks preserved in the rocks of the Berriasian-aged Buckeburg Formation. Seven trails were present in all and their arrangement showed evidence for herding behavior among the trackmakers.[119]

- Giuseppe Leonardi erected the new ichnogenus and species Brasilichnium elusivum to classify the Early Jurassic proto-mammal tracks from the Botucatu Sandstone of Brazil.[120]

- Thulborn criticized the idea that the hadrosaur tracks reported by Brown in 1938 were left by a running animal.[104]

- Demathieu and Haubold described the new Early Triassic ichnogenus and species Isochirotherium archaem from Germany. As only the hind prints are preserved in this trackway it may represent the oldest evidence in the world for the existence of animals with bipedal gaits. However, while intriguing, their remains the possibility that the track maker was a quadruped and its foreprints eroded away before the trail was discovered.[121]

- Demathieu and Marc Weidmann described a new Triassic fossil tracksite from Switzerland called the Vieux Emosson tracksite.[122]

- Geology student Jeff Pittman recognized that the "potholes" hindering excavation equipment traffic through a gypsum mine in southeastern Arkansas were actually sauropod dinosaur footprint.[123]

- Hartmut Haubold published the Saurierfahrten.[124] Haubold was a German ichnologist, and the Saurierfahrten a specialist's handbook for identifying Carboniferous and Permian fossil footprints. It was the only publication of its type in the world at the time and only available in German.[125]

- Paul Olsen and Peter Galton argued that Ellenberger had oversplit the Late Triassic and Early Jurassic ichnotaxa he studied and that many of the kinds of tracks he regarded as distinct were the tracks previously described in eastern North America.[126]

- J. E. Andrews and J. D. Hudson reported the first dinosaur tracks to be scientifically documented in Scotland. The tracks are three-toed and preserved in the Middle Jurassic Leate Shale.~144~

- George Demathieu and others described an Oligocene bird and mammal track site from southeastern France. Three different mammalian ichnotaxa were present. One was an artiodactyl track they named Bifidipes velox. The second was the largest of the three, Ronzotherichnus, was apparently left by the rhinoceros Ronzotherium. A creodont or early carnivoran left behind the third kind of tracks, which the researchers named Sarcotherichnus enigmaticus. They named the bird tracks at the site Pulchravipes magnificus.[84]

- Kevin Padian and Paul Olsen reinterpreted the supposed pterosaur tracks named Pteraichnus from the Morrison Formation of Utah as crocodilian tracks.[120]

- Luis Aguirrezabala reported the presence of nine parallel trails left by Hypsilophodon or one of its close relatives in Lower Cretaceous rocks of La Rioja, Spain. This tracksite is now known as the Valdevajes site.[127]

- An international symposium for paleontologists performing research on "Dinosaur Tracks and Traces" was held in New Mexico.[128] The gathering was a success and "led to the rejuvenation and maturing of the discipline of dinosaur ichnology".[129]

- Scrivener and Bottjer published a census of tracks from the Miocene Copper Canyon Formation of Death Valley National Monument, California. Most of these footprints were camel tracks, but bird and horse prints were also common. Less common traces included those of bear-dogs, cats, deer, and proboscideans.[130]

- Lockley, Houck, and Prince first described the Purgatoire Valley dinosaur tracksite.[69]

- Paul Ensom reported dinosaur tracks from the Purbeck Limestone of Dorset, England.[131]

- Lockley disputed Robert T. Bakker's hypothesis that an Early Cretaceous sauropod trackway from the Davenport Ranch, Texas area preserves evidence that sauropods traveled in herds with the young surrounded by the adults to protect them from predators. Instead, Lockley interpreted this trackway as a herd of sauropods traveling through a narrow area, with the young following the adults.[132]

- Lockley and Hunt began studying the dinosaur tracks of the Dakota Group at the Alameda Parkway site, which is now called Dinosaur Ridge.[133]

- Lockley described the ichnogenus Caririchnium. This publication was also the first detailed treatment of the Dakota Group's trace fossil record in the scientific literature.[134]

- Robert E. Weems published the results of his research into the Late Triassic reptile tracksite near Culpeper, Virginia. Among the fossil footprints he found there were the dinosaur ichnogenera Agrestipus, Grallator, Gregaripus, and Kayentapus.[102]

- Harald von Walter and Ralf Werneberg reported the discovery of body impressions left behind by diplocaulid amphibians in the Rotliegende of the Thuringian Forest area. The assemblage includes the body impression of several individuals, all no more than a few centimeters in length.~46~ The authors named these traces Hermundurichnus fornicatus.[135]

- Lockley and Hunt rediscovered fossil bird footprints in the Dakota Group near Golden Colorado.[136] Among the specimens recovered was the first in the world to preserve dinosaur and bird footprints together.[137]

- Lockley reported the first observation in the Dakota Group of dinosaur footprints with preserved skin impressions.[134]

- W. A. S Sargeant and J. A. Wilson reported the presence of Eocene mammal footprints in Texas.[138]

- R. Santamaria, G. Lopez, and M. L. Casanovas-Cladellas reported an Oligocene mammal track site discovered near Agramunt, Spain. This tracksite preserved four new ichnospecies, three of which were in new ichnogenera. First was a new species of Bothriodontipus, which was made by the pig-like animal Bothriodon or a close relative. The researchers new ichnogenera were Creodontipus and Plagiolophustipus.[84] They classified two of their new ichnospecies in Creodontipus, an ichnogenus they fittingly attributed to creodonts. They attributed Plagiolophustipus to tapir-like animals distantly related to horses.[139]

- Jeff Pittman proved that the sauropod tracks he recognized in an Arkansas gypsum mine were actually at the same level of the geologic column as the Glen Rose Formation sauropod tracks of Texas.[140]

- Farlow, Pittman, and Hawthorne described the ichnogenus Brontopodus.[60]

- April: A quarry worker named Robert Clore blasting stone near Culpeper, Virginia uncovered a new Late Triassic reptile tracksite.[141] Weems began studying the site that same year, and reported the presence of 4,000 individual tracks. The local tracks included the dinosaur ichnogenera Grallator and Kayentapus. Other tracks may have been left by aetosaurs.[142]

1990s[edit]

- Ryszard Fuglewicz and others reported fossil trackways from the Holy Cross Mountains of Poland that may be the oldest Triassic trackways in Europe. They reported tracksites at six different positions within a stratigraphic series in several distinct paleoenvironments including river channels and floodplains. The ichnogenera they identified in these tracksites included Brachychirotherium, Capitosauroides, Isochirotherium, Rhynchosauroides, and Synaptichnium.[143]

- Demathieu reported the presence of dinosaur tracks at Saint-Leons and Saint-Laurent de Tives in the Causses region of France.[144]

- Lockley disputed claims that some sauropod tracks were left underwater by swimming trackmakers.[134]

- A track site containing more than 250 fossil bird footprints was discovered ear Villar del Rio, Spain.[145]

- Robison reported shorebird footprints in the Cretaceous Mesa Verde Group of Utah. He also reported the presence of the oldest known frog tracks.[146]

- Lockley argued that the supposed sauropod tracks reported by Ensom from the Purbeck Beds of Dorset, England were actually made by ankylosaurs.[147]

- Lockley described the Moab megatracksite.[69]

- C. Lancis and A. Estevez reported the presence of early Pliocene tracks preserved near Alicante, Spain. Among the mammals who left their mark here were members of the horse family and bears.[148]

- Farlow observed that sauropod trackways could be categorized as either being "narrow-gauge" or "wide-gauge".[149]

- Mid November: Lockley and Hunt's research group at the University of Colorado undertook one of the few major dinosaur footprint excavations in history in order to expand the exposed track-bearing surface at Dinosaur Ridge for an outdoor interpretive center.[150]

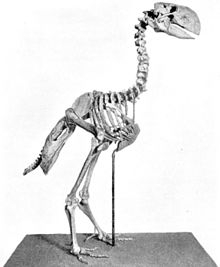

- May 3rd: The Seattle Times reported the discovery of a potential Diatryma track in the Eocene Puget Group of Flaming Geyser State Park, Washington.[151]

- Lockley and Madsen published ichnological evidence for the predation of large reptiles on smaller animals during the Permian period.[152]

- Lockley and dos Santos described the Kimmeridgian-aged Avelino quarry tracksite near Lisbon, Portugal, the first scientifically documented sauropod dinosaur tracksite in Europe to contain well-preserved tracks of the animals' front feet. All of the trackmakers seem to have been juveniles.[153]

- Meyer reported the first scientifically documented Late Jurassic dinosaur footprints from Switzerland. These tracks were discovered near the town of Lommiswil.[154]

- Claude Guerin and George Demathieu described the new ichnospecies Dicerotichnus laetoliensis. This ichnospecies was left behind by a late Pliocene rhinoceros of fairly modern build, possibly from the genus Diceros. Its tracks are preserved at the same site known for its ancient hominid tracks.[84]

- A non-technical article in the Spanish magazine Blanco y Negro discussed the wide variety of Miocene tracks preserved at Salinas de Anana, Spain.[155]

- Lockley and Hunt introduced the idea of ichnofacies to the scientific literature. They described and named the Brontopodus ichnofacies based on sauropod tracksites in Texas.~NA210~[citation needed]

- A new tracksite was discovered in Toadstool Park area of Nebraska's Oglala National Grassland.[156] Eleven different trackmakers have been documented here, including camels, carnivorans, ducks, rhinoceroses, and shorebirds.[157]

- Late: An expansive Late Triassic dinosaur tracksite was discovered at the Pennsylvania State Correctional Institution in Graterford.[158]

- Lockley and others argued that Deltapodus was probably not left by a sauropod because the hind prints had only three toes and the tracks themselves were preserved in an environment where sauropod tracks are not generally found.~135~ Instead they concluded it was more likely to be the tracks of a thyreophoran, possibly a stegosaur.[159]

- A cave enthusiast near Fatima, Portugal looked down on a quarry from a high ridge and noticed that its floor was covered in sauropod footprints.[160] The site included the longest known dinosaur trails at the time. The individual tracks are the largest sauropod prints known from the Middle Jurassic and include the largest foreprints of any known sauropod track type.[161]

- Lockley, Hunt, and Meyer defined the Brontopodus ichnofacies.

- Galopim published The Battle of Carenque, a book describing the successful efforts of Portuguese conservationists to save the home of the world's longest dinosaur trackway from being destroyed by freeway construction.[162]

- A major collaborative research venture between the US Bureau of Land Management, the New Mexico Museum of Natural History, the Smithsonian, and the University of Colorado began aimed at studying the Permian-aged tracks of the Abo Formation in New Mexico.[163]

- Bill Sarjeant and Wann Langston published a monograph on the late Eocene track site from the Vieja Group of Texas. The tracks preserved there indicate a fauna including six kinds of bird, two kinds of invertebrate, nineteen mammal species, and two kinds of turtle.[164]

- Hunt, Lockley, and Lucas reported the existence of a fossil trackway preserving an apparent act of predation of a pelycosaur upon a small reptile.[29]

- Lockley, Hunt, and Meyer proposed the idea of vertebrate ichnofacies.[25]

- Lockley and Hunt defined the Brontopodus and Caririchnium ichnofacies.[134]

- Iwan Stossel reported the oldest known fossil vertebrate footprints in Europe to the scientific literature.[165] The tracks were preserved in the Mid-Late Devonian Valentia Slate of Valentia Island, which lies off the southwestern coast of Ireland. Roughly 150 tracks were present in an 8 meter long trail left behind by an early tetrapod.[166]

- David Scarboro and Maurice Tucker reported the discovery of a fossil trail probably left by a temnospondyl amphibian about 1.5 meters long walking through a delta during the Middle Carboniferous. The find is one of the largest Carboniferous fossil trackways in all of Europe.[167]

- Jean-Michel Mazin and others described the first scientifically documented pterosaur fossils from Europe. These tracks were preserved in a Late Jurassic limestone in Crayssac, France.[168] The pterosaurs that left these footprints seem to have been in the sparrow to sea gull size range. These tracks have played a "pivotal" role in confirming that various unusual and controversial trace fossils reported around the world really were made by pterosaurs after all.[169]

- April: Fabio Dalla Vecchia and one of his students were arrested while mapping dinosaur footprints in Croatia and inadvertently following the tracks into a military zone. They were tried and subsequently fined their trial expenses and released.[170]

- Koenigswald, Walders, and Sander described a 30,000- to 20,000-year-old Pleistocene fossil mammal track site from Bottrop, Germany. Local trackmakers included bison, horses, cave lions, reindeer, and wolves.[171]

- Price argued that scholars generally underestimated how long ago humanity first domesticated horses based on a Bronze Age tracksite in Sweden.[172]

- Phylis Jackson argued that the pedal anatomy of Anglo-Saxon and Celtic peoples are so distinct that these populations can be distinguished based on feet alone going all the way back to the Neolithic.[173] Celtic people have narrower feet while Anglo-Saxon feet are broader.[174]

- Fuentes Vidarte reported the oldest known bird tracks in the world from the Berriasian Wealden Beds of the Villar del Rio, Spain.[145]

- Fabio Dalla Vecchia returned to Croatia and finished mapping the dinosaur footprints with Croatian geologist Igor Vlahovic.[175]

- Fabio Dalla Vecchia and Marco Rustioni reported a Miocene mammal tracksite in the Conglomerato di Osoppo in Udine Province, Italy. Across its 100 square meter area the track site preserved the footprints of three different kinds of large mammal.[79]

- The first international workshop on Paleozoic footprint fossils, presided over by Hartmut Haubold was held in Germany.[128] The symposium was such a success that it is regarded as a turning point in the history of Paleozoic vertebrate ichnology.[129]

- Avanzini, van den Dreissche and Keppens concluded that the tracks preserved at Lavini de Marco in Italy were cemented through chemical processes trigger by the rapid evaporation of water from the carbonate track-bearing substrate and speculated that similar circumstances may have preserved tracks in carbonates at other sites and different positions in the stratigraphic column.[176]

- Meyer reported that the Late Jurassic dinosaur tracks discovered near Lommiswil, Switzerland were actually part of a gigantic megatracksite. This was the first report of a dinosaur megatracksite in Europe.[177]

- Wright and others re-examined the Purbeckopus pentadactylus tracks from Dorset, England and concluded that not only were they pterosaur tracks, but they were among the largest known pterosaur tracks in the fossil record.[81]

- Felix Perez-Lorente reported evidence for quadrupedal locomotion among Berriasian iguanodont footprints preserved in the Villar del Arzobispo Formation not far from Galve, Spain.[178]

- Tuner and Anton attributed Miocene cat footprints found at Salinas de Anana, Spain to the genus Pseudaelurus. These tracks may in fact be the oldest known cat footprints in the world.[155]

- Phylis Jackson published further research on the use of pedal anatomy and footprints to distinguish different groups of people.[173]

- Lockley, dos Santos, and Hunt found the purported hypsilophodont tracks of the Spanish Valdavajes tracksite similar to the Late Jurassic ichnogenus Dinehichnus that has been attributed to dryosaurids.[127]

- Lopez-Martinez and others noted the presence of sauropod and ornithopod tracks near the K-T Boundary in the Tremp Formation of northeastern Spain. The presence of tracks so close to the Cretaceous-Tertiary suggests that the dinosaur died out rapidly rather than gradually.[179]

See also[edit]

Footnotes[edit]

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "A Miocene Menagerie", page 255.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Iguanodon and Conan Doyle's Lost World", page 201.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Story of Chirotherium: The Dawn of the Archosaurs", pages 56–57.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Story of Chirotherium: The Dawn of the Archosaurs", pages 57–58.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "'Swimming' Brontosaurs and the Dangers of Misinterpretation", page 186 and "Digging for Dinosaur Tracks", page 199.

- ^ a b c d e Lockley and Hunt (1995); "What's in a Name?", page 144.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Pterosaur Tracks Dispute", pages 140–143.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Parallel Trackways and Dinosaur Herds", pages 196–197 and "The Dinosaur Freeway", page 209.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); For role of the dinosaur renaissance, see "Preface", page xvi. For paleontologists' need for data following the publication of Alexander's formula, see "The Case of the 'Mystery Dinosaur'", page 221.

- ^ ">Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Preface", page xvi.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The German Summit Conference", page 44.

- ^ a b c d Weishampel and Young (1996); "More Early Footprints", page 63.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Tracks Versus Bones", pages 177–178.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "More Early Footprints", page 61.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "Theropoda: Tracking and Attacking in the Triassic", page 98.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "2. Were the Tracks Made by Representatives of the Genus Iguanodon Only, and If So, Which Species?" page 195.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Subterranean Tracking: Hominid Ichnology", page 261.

- ^ a b c d Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Paleocene Tracks and the Survivors of the Mass Extinction", page 246.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Dinosaurs in the Great Deltas of Yorkshire", page 133.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Lyons Sandstone: Twin of the Coconino", page 44.

- ^ Moore (2014); "1913" (3), page 150.

- ^ Moore (2014); "1914" (5), page 153.

- ^ a b c Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", page 34.

- ^ a b c Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Megalosaur Tracks", page 152.

- ^ a b c Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 2: The Paleozoic Era", page 314.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Case of the 'Mystery Dinosaur'", page 217.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "Virginia (Midland Formation)", page 105.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Story of Chirotherium: The Dawn of the Archosaurs", page 57.

- ^ a b c Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 2: The Paleozoic Era", page 313.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Tracks as Keys to Evolution and Locomotion", page 60.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Subterranean Tracking: Hominid Ichnology", page 262.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act II: An Abundance of Waterfowl", page 252.

- ^ Moore (2014); "1929" (8), page 182.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Carboniferous Tracks: Amphibian, Reptile, or Other?", page 37–38.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Latest Big Discovery", page 57.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Eastern Region of the Chinle", page 88.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Parallel Trackways and Dinosaur Herds", page 201.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Case of the Carson City 'Man Tracks'", page 280.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Tracks Along the Shores of the Western Interior Seaway", pages 194–195.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Early Cretaceous Bird and Crocodile Tracks", page 211.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Western Traces in the 'Age of Amphibians'", page 35.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Northern Colorado Plateau Region of the Chinle", pages 93–94.

- ^ a b c d e Weishampel and Young (1996); "More Early Footprints", page 64.

- ^ a b c d Weishampel and Young (1996); "More Early Footprints", page 66.

- ^ Moore (2014); "1933" (1), page 192.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Parallel Trackways and Dinosaur Herds", pages 196–197.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Parallel Trackways and Dinosaur Herds", page 197.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Case of the 'Mystery Dinosaur'", pages 219–220.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Case of the 'Mystery Dinosaur'", page 220.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Case of the 'Mystery Dinosaur'", pages 220–221.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Turtles and Hopping Dinosaurs", page 178.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "'Stone Tracks' of the Coconino Sandstone", page 43.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "An Overview of Early Cretaceous Tracks", pages 184–185.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "More Early Footprints", pages 64–66.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Moenkopi of the Early and Middle Triassic", pages 71–72.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Digging for Dinosaur Tracks", page 199.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Linking Tracks with the Trackmakers", page 274.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Von Huene's Little Dinosaur Track: Coelurosaurichnus", page 95.

- ^ a b c Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 5: The Cretaceous", page 318.

- ^ a b c d e f g Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 6: The Cenozoic Era", page 321.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Puzzle of Miocene Tracks in the Oligocene", page 257.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Puzzle of Miocene Tracks in the Oligocene", pages 257–258.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 3: The Triassic", page 316.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Subterranean Tracking: Hominid Ichnology", page 260.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Case of the 'Mystery Dinosaur'", page 221.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Megalosaur Tracks", page 154.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Carboniferous Tracks: Amphibian, Reptile, or Other?", page 36.

- ^ a b c d Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 4: The Jurassic", page 317.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Megalosaur Tracks", pages 152–153.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Megalosaur Tracks", page 153.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 2: The Paleozoic Era", page 312.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Interpreting Tracks and Track Habitats", page 51.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Theropod Tracks", pages 207–208.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Arctic Dinosaurs", page 220.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Arctic Dinosaurs", pages 220–222.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Arctic Dinosaurs", page 222.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "One-of-a-Kind Tracks from the Eocene", pages 252–253.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "A Miocene Menagerie", page 252.

- ^ a b Moore (2014); "1962" (5), page 244.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Archosaurs in the Air (Pterosaurian Giants)", page 189.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Story of Chirotherium: The Dawn of the Archosaurs", page 58.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act II: An Abundance of Waterfowl", pages 251–252.

- ^ a b c d Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act I: Tracking Ronzotherium, An Early Rhino", page 246.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Underground Hazards", page 227.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "Leaksville Junction", pages 188–189.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The World's Oldest Dinosaur Tracks: Fact, Fiction, and Controversy", page 68.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The World's Oldest Dinosaur Tracks: Fact, Fiction, and Controversy", page 67.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Further Along the Trail of the Elusive Ankylosaur", page 216.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act II: An Abundance of Waterfowl", page 248.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Kayenta Tracks and the Problem of 'Provincial Taxonomy'", page 119.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 4: The Jurassic", page 318.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act II: An Abundance of Waterfowl", page 249.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Ancient Ships of the Desert", page 267.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "New York", page 172.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Interpreting Tracks and Track Habitats", pages 55–56.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Sauropods on the Rise: Germany, Iberia, and Switzerland", page 159.

- ^ "Ancorichnus Heinberg". Ichnopolis.dk. Tina A. Kjeldahl-Vallon & Lothar H. Vallon. Retrieved 5 December 2017.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The First Pareiasaur Trackway", page 47.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Mr. Pooley's Enigmatic Track Discovery", page 143.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Mr. Pooley's Enigmatic Track Discovery", pages 143–144.

- ^ a b Weishampel and Young (1996); "Culpeper", page 186.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 5: The Cretaceous", page 320.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Welsh Dinosaurs at the Jolly Sailor Pub", page 80.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Welsh Dinosaurs at the Jolly Sailor Pub", page 81.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Real Pterosaur Tracks Story", page 160.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Arctic Dinosaurs", page 224.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "What's in a Name?", pages 144–145.

- ^ Moore (2014); "1978" (7), page 274.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Part II: Cruising the Carboniferous", page 32.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Last of the Brontosaurs: Tracking Titanosaurs in the High Pyrenees", page 234.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act II: An Abundance of Waterfowl", page 250.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act II: An Abundance of Waterfowl", pages 249–251.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Rare Tracks of the Laramie Formation", page 229.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Quiet Dawn: Paleocene-Eocene", page 244.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Mammoths of the Pleistocene", pages 275–276.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "Theropoda: Skeletons. Fires, and Footprints", page 114.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Sauropod Tracks", page 209.

- ^ a b Lockley and Hunt (1995); "What's in a Name?", page 145.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Tracks as Keys to Evolution and Locomotion", page 61.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Lizard Ancestors and Proto-Mammals with Hairy Feet", pages 65–67.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Problematic Potholes", pages 191–192.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Bibliographic Notes", page 50.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Part II: Cruising the Carboniferous", pages 33–34.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The March of the Prosauropods", pages 84–85.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Ornithopod Tracks", page 211.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The German Summit Conference", page 44.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The German Summit Conference", page 45.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Camels, Bear-Dogs, and Other Denizens of the Miocene", pages 269–270.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The First Ankylosaur Tracks", page 182.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "'Swimming' Brontosaurs and the Dangers of Misinterpretation", page 186.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Dinosaur Freeway", page 209.

- ^ a b c d Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 5: The Cretaceous", page 319.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Stuck in the Mud: The Complete Trace of a Hammerhead Amphibian", page 47.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Tracks Along the Shores of the Western Interior Seaway", pages 194–196.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Tracks Along the Shores of the Western Interior Seaway", page 196.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 6: The Cenozoic Era", page 322.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Oligocene Act I: Tracking Ronzotherium, An Early Rhino", pages 246–247.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Problematic Potholes", page 192.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "Culpeper", pages 186–188.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "Culpeper", page 188.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Future Directions", page 71.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "France: The Causses Region", page 111.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Archosaurs in the Air (Pterosaurian Giants)", page 191.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Bird, Frog, Pterosaur(?) and Baby Dinosaur(?) Tracks", pages 225-226.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The First Ankylosaur Tracks", pages 182-183.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Pliocene Interlude", page 256.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Sauropod Straddle", page 175.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Digging for Dinosaur Tracks", pages 199–200.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Big Bird Tracks Have Paleontologists All Aflutter", page 262.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "Chapter 2: The Paleozoic Era", pages 313–314.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Baby Brontosaurs", page 162.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Swiss Megatracksite", pages 169–171.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Tracking Ancestors of the Cat: Miocene of Spain", page 255.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Puzzle of Miocene Tracks in the Oligocene", page 260.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Puzzle of Miocene Tracks in the Oligocene", page 261.

- ^ Weishampel and Young (1996); "Graterford", page 185.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Dinosaurs in the Great Deltas of Yorkshire", pages 135–136.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The First Iberian Sauropods", page 138.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The First Iberian Sauropods", page 139.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Battle of Carenque", pages 229–230.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "The Latest Big Discovery", pages 57–61.

- ^ Lockley and Hunt (1995); "One-of-a-Kind Tracks from the Eocene", page 256.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Part I: Dragging Through the Devonian", page 29.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Part I: Dragging Through the Devonian", pages 29–30.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Part II: Cruising the Carboniferous", page 34.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Spoor of the Pterosaur", page 178.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Spoor of the Pterosaur", page 180.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Dalmatian Dinosaurs", pages 217–218.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Pleistocene: Ice Age Trackmakers", page 257.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Cave Art to Forensics: The Signature of Modern Humanity", page 265.

- ^ a b Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Cave Art to Forensics: The Signature of Modern Humanity", page 268.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Figure 10.15" page 269.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Dalmatian Dinosaurs", page 218.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The First Sauropods? Evidence From Italy", page 129.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Swiss Megatracksite", page 171.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "Ornithopod Tracks", pages 209–211.

- ^ Lockley and Meyer (2000); "The Last European Dinosaurs", page 239.

References[edit]

- Lockley, Martin G.; Hunt, Adrian (1995). Dinosaur Tracks and Other Fossil Footprints of the Western United States. Columbia University Press. p. 338. ISBN 978-0231079266.

- Lockley, Martin G.; Meyer, C. A. (2000). Dinosaur Tracks and other fossil footprints of Europe. New York: Columbia University Press. ISBN 0-231-10710-2.

- Moore, Randy (2014). Dinosaurs by the Decades: A Chronology of the Dinosaur in Science and Popular Culture. Santa Barbara: Greenwood. p. 472. ISBN 978-0-313-39364-8.

- Weishampel, David B.; Young, L. (1996). Dinosaurs of the East Coast. Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 9780801852169.

External links[edit]

Works related to Ichnology at Wikisource

Works related to Ichnology at Wikisource