Ajahn Brahm

Ajahn Brahm | |

|---|---|

Ajahn Brahm in 2008 | |

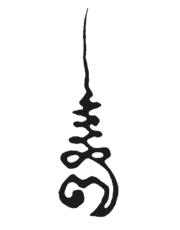

| Title | Phra Visuddhisamvarathera |

| Personal | |

| Born | Peter Betts 7 August 1951 London, England |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| School | Theravada |

| Education | Emmanuel College, Cambridge |

| Occupation | Bhikkhu (monk) |

| Senior posting | |

| Teacher | Ajahn Chah Bodhinyana |

| Based in | Bodhinyana Monastery |

| Website | Official page |

| Thai Forest Tradition | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Bhikkhus | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Sīladharās | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Related Articles | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Phra Visuddhisamvarathera AM (Thai: พระวิสุทธิสังวรเถร), known as Ajahn Brahmavaṃso, or simply Ajahn Brahm (born Peter Betts[1] on 7 August 1951), is a British-born Theravada Buddhist monk. Currently, Ajahn Brahm is the abbot of Bodhinyana Monastery in Serpentine, Western Australia; Spiritual Adviser to the Buddhist Society of Victoria; Spiritual Adviser to the Buddhist Society of South Australia; Spiritual Patron of the Buddhist Fellowship in Singapore; Patron of the Brahm Centre in Singapore; Spiritual Adviser to the Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project in the UK; and Spiritual Director of the Buddhist Society of Western Australia (BSWA). He returned to the office on 22 April 2018 after briefly resigning in March, following a contentious vote by members of the BSWA during their annual general meeting.[2]

Early life[edit]

Peter Betts was born in London.[1] He came from a working-class background and went to Latymer Upper School.[citation needed] He won a scholarship to study theoretical physics[3] at Emmanuel College, University of Cambridge in the late 1960s.[4] After graduation, he taught mathematics at a high school in Devon for one year before travelling to Thailand to become a monk and train with Ajahn Chah Bodhinyana Mahathera.[1] Brahm was ordained in Bangkok at the age of twenty-three by Somdet Kiaw, the abbot of Wat Saket. He subsequently spent nine years studying and training in the forest meditation tradition under Ajahn Chah.

Bodhinyana Monastery[edit]

After practicing for nine years as a monk, Ajahn Brahm was sent to Perth by Ajahn Chah in 1983 to assist Ajahn Jagaro in teaching duties.[5] Initially, they both lived in an old house on Magnolia Street, in the suburb of North Perth, but in late 1983, they purchased 97 acres (393,000 m²) of rural and forested land in the hills of Serpentine, south of Perth.[1] The land was to become Bodhinyana Monastery (named after their teacher, Ajahn Chah Bodhinyana). Bodhinyana was to become the first dedicated Buddhist monastery of the Thai Theravada lineage in the Southern Hemisphere and is today the largest community of Buddhist monks in Australia.[citation needed] Initially, there were no buildings on the land and as there were only a few Buddhists in Perth at this time, and little funding, the monks themselves began building to save money. Ajahn Brahm learnt plumbing and bricklaying and built many of the current buildings himself.

In 1994, Ajahn Jagaro took a sabbatical leave from Western Australia and disrobed a year later. Left in charge, Ajahn Brahm took on the role and was soon being invited to provide his teachings in other parts of Australia and Southeast Asia. He has been a speaker at the International Buddhist Summit in Phnom Penh in 2002 and at three Global Conferences on Buddhism.[citation needed] He also dedicates time and attention to the sick and dying, those in prison or ill with cancer, people wanting to learn to meditate, and also to his Sangha of monks at Bodhinyana.[citation needed] Ajahn Brahm has also been influential in establishing Dhammasara Nuns' Monastery at Gidgegannup in the hills northeast of Perth to be a wholly independent monastery, which is jointly administered by Ayya Nirodha and Venerable Hasapañña.[citation needed]

Bhikkhuni ordination[edit]

On 22 October 2009, Ajahn Brahm, along with Bhante Sujato, facilitated an ordination ceremony for bhikkhunis, where four female Buddhists, Venerable Ajahn Vayama, and Venerables Nirodha, Seri, and Hasapañña, were ordained into the Western Theravada Bhikkhuni Sangha, with Venerable Tathālokā Bhikkhunī serving as Bhikkhunī Preceptor.[6][7] The ordination ceremony took place at Ajahn Brahm's Bodhinyana Monastery at Serpentine, Australia. Although bhikkhuni[8] ordinations had taken place in California and Sri Lanka, this was the first in the Thai Forest Tradition and proved highly controversial in Thailand. There is no consensus in the wider tradition that bhikkhuni ordinations could be valid, having last been performed in Thailand over 1,000 years ago, though the matter has been under active discussion for some time. Ajahn Brahm claims that there is no valid historical basis for denying ordination to bhikkunis.[citation needed]

I thought too when I was a young monk in Thailand that the problem was a legal problem, that the bhikkhuni order couldn't be revived. But having investigated and studied, I've found out that many of the obstacles we thought were there aren't there at all. Someone like Bhikkhu Bodhi [a respected Theravada scholar–monk] has researched the Pali Vinaya and his paper is one of the most eloquent I've seen—fair, balanced, comes out on the side of "It's possible, why don't we do this?"[9]

For his actions of 22 October 2009, on 1 November 2009, at a meeting of senior members of the Thai forest monastic Sangha in the Ajahn Chah lineage, held at Wat Pah Pong, Ubon Ratchathani, Brahm was removed from the Ajahn Chah Forest Sangha lineage and is no longer associated with the main monastery in Thailand, Wat Pah Pong, nor with any of the other Western Forest Sangha branch monasteries of the Ajahn Chah tradition.[10]

Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project[edit]

In October 2015, Ajahn Brahm asked Venerable Candā of Dhammasara Nun's Monastery, Perth, to take steps towards establishing a monastery in the UK. In response to this, Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project was born. Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project aims to promote the teachings and practices of early Buddhism by establishing a Bhikkhuni presence in the UK. Its long-term aspiration is to develop a monastery with a harmonious and meditative atmosphere, for women who wish to train towards full ordination.[11][12]

"The reason I'm going over to the UK is [because] . . . I have a sense of responsibility to the place of my birth. It was a very wonderful society and inculcated many values in me. One of those values was fairness, where people are given equity. I came from a poor background, it was disadvantaged, but because of the fairness of the system I could, through the means of scholarships, go to a very good high school, and from [there] to a very good university. I was given a chance, and I see in the UK right now, women in Theravada Buddhism are not given a chance; because of their birth they are not permitted to take full ordination in Theravada Buddhism, which, personally, because of my upbringing, [I think] is unacceptable. And also because of my upbringing, I always say, 'Don't just complain about things, do something!' And it happens at this time in my monastic life that I am able to do things. I have many disciples and some of those disciples want to give some of their money for a good cause. So the next project . . . is to try and get a nice start for the bhikkhuni sangha in the UK . . . [where] a good nun like Bhikkhuni Candā has a place to stay and a place to teach. At the moment she has nowhere, really, absolutely nowhere to stay! So the requisite of lodgings is primary.

"The main guidance [for bhikkhunis] . . . is the Buddha—you take refuge in the Buddha, the Dhamma, and the sangha [as a whole] . . . [in] the guidelines of simplicity, frugality, kindness, compassion, and mindfulness, [which] are part of the Vinaya training. When it comes to other training, I'll say in this interview, I have full confidence in Venerable Candā to be a leader. She doesn't have that confidence in herself yet, but I do. It's a case of, you take these people, put them in the deep end of the water, and my goodness, they swim! And no one is more surprised than they themselves that they can keep their heads above water.

"This monastery is going to happen . . . it's just a matter of time. . . . [The bhikkhuni sangha] is the fourth leg of the chair of Buddhism, this is what the Buddha kept on saying. After he became enlightened under the banyan tree, Mara came to him and said, 'Okay, you're enlightened, I admit it. Now don't go teaching, it's just too burdensome. Just enter parinibbana now, just disappear'. The Buddha said, 'No, I will not enter parinibbana. I will not leave this life until I have established the bhikkhu sangha, bhikkhuni sangha, laymen, and laywomen Buddhists: the four pillars of Buddhism'. Forty-five years later, at the Capala Shrine, Mara came again and said, 'You've done it! There are lots and lots of bhikkhunis enlightened, lots of bhikkhus enlightened, great laymen and laywomen Buddhists . . . so keep your promise', and [the Buddha] said, 'Okay, in three months, I'll enter parinibbana'.

What those two passages from the suttas demonstrate is that it was the Buddha's mission; it was why he taught—to establish those four pillars of the sangha. We have lost one, so every Buddhist who has faith in the Buddha should actually help the Buddha re-establish the bhikkhuni sangha. It was his mission, [but] because of history his mission has been thwarted".[13]

LGBT support[edit]

Ajahn Brahm has openly spoken about his support towards same-sex marriage. At a conference in Singapore in 2014, he said he was very proud to have been able to perform a same-sex marriage blessing for a couple in Norway, and stressed that Buddhist teachings do not discriminate on the basis of sexual orientation.[14][15]

Rohingya crisis[edit]

In 2015, during the Rohingya refugee crisis, the Buddhist Society of Western Australia donated money to support displaced orphans in Bangladesh. Speaking at the ceremony, Ajahn Brahm said:

No matter what race or religion you are, we always look after one another. All religions are brothers and sisters, so we care for one another. So may violence and mistrust disappear and kindness and love and helping one another prevail.[16]

Kindfulness[edit]

In an effort to reclaim the "mindfulness" practice from being overrun by secular industries and a recent claim that it is not owned by Buddhism, Ajahn Brahm clarifies that mindfulness is a practice within the rest of the supporting factors of Buddhism (the Noble Eightfold Path: right view, right motivation, right speech, right action, right livelihood, right endeavor, right mindfulness, and right stillness). According to the monk, mindfulness is part of a great training called Buddhism, and to actually take away mindfulness from Buddhism is unhelpful, inaccurate, and deceiving—mindfulness is a cultural heritage of Buddhism. Practicing mindfulness without wisdom and compassion is not enough. Therefore, drawing from the Pāli Suttas,[17] Ajahn Brahm created the term "Kindfulness", meaning mindfulness combined with wisdom and compassion—mindfulness combined with knowing the ethical and moral compassionate consequences of the reactions to what is happening (a.k.a. satisampajañña).[18]

Achievements[edit]

Whilst still a junior monk, Ajahn Brahm was asked to undertake the compilation of an English-language guide to the Buddhist monastic code—the vinaya.[19] Currently, Brahm is the Abbot of Bodhinyana Monastery in Serpentine, Western Australia,[20] the Spiritual Director of the Buddhist Society of Western Australia, Spiritual Adviser to the Buddhist Society of Victoria, Spiritual Adviser to the Buddhist Society of South Australia, Spiritual Patron of the Buddhist Fellowship in Singapore and most recently, Spiritual Adviser to the Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project in the UK.[21]

In October 2004, Ajahn Brahm was awarded the John Curtin medal for his vision, leadership, and service to the Australian community, by Curtin University.

Under the auspices of the Diamond Jubilee of King Rama IX, Bhumibol Adulyadej, in June 2006, Ajahn Brahm was given the title of Phra Visuddhisamvarathera,[22] a Royal Grade Thai ecclesiastical title once held by Ajahn Liem, the current abbot of Wat Nong Pah Pong.[citation needed]

On 5 September 2019, Ajahn Brahm was awarded the Order of Australia, General Division medal, for services to Buddhism and gender equality. The investiture was performed at Government House Western Australia.[23]

Publications[edit]

- Opening the Door of Your Heart: and Other Buddhist Tales of Happiness. Also published as Who Ordered This Truckload of Dung?: Inspiring Stories for Welcoming Life's Difficulties. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-0861712786 (2005)

- Mindfulness, Bliss, and Beyond: A Meditator's Handbook. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-275-7 (2006)

- The Art of Disappearing: Buddha's Path to Lasting Joy. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 0-86171-668-X (2011)

- Don't Worry, Be Grumpy: Inspiring Stories for Making the Most of Each Moment. Also published as Good? Bad? Who Knows?. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-1614291671 (2014)

- Kindfulness. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-1614291992 (2016)

- Bear Awareness: Questions and Answers on Taming Your Wild Mind. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-1614292562 (2017)

- Falling Is Flying: The Dharma of Facing Adversity – with Guo Jun. Wisdom Publications. ISBN 978-1614294252 (2019)

Publications by BPS[edit]

- In the Presence of Nibbana (BL149)

- Ending of Things (BL153)

- Walking Meditation: The Expositions on Walking Meditation (WH464) (with Ajahn Nyanadhammo and Dharma Dorje)

- Opening the Door of Your Heart (BP619s)

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d "I Kidnapped a Monk!". Buddhistdoor Global. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ Bellamy, Drew (24 March 2018). "Ajahn Brahm Resigns". Buddhist Society of Western Australia. Retrieved 25 March 2018.

- ^ "Buddhism, the only real science". Daily News. Archived from the original on 28 July 2012. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Chan, Dunstan (2013). Sound and Silence. TraffordSG. p. 189. ISBN 9781466998759.

- ^ Wettimuny, Samantha (21 January 2007). "Sharing the Dhamma in his own unique style". Sunday Times (Sri Lanka). 41 (34). ISSN 1391-0531.

- ^ "History in the Making?". Go Beyond Words: Wisdom Publications blog. 3 November 2009. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ Thanissara. "The Time Has Come - Lion's Roar". Retrieved 13 February 2022.

- ^ Zoltnick & McCarthy. "2600 Year Hourney History of Bhikkhunis". Present Magazine. Alliance for Bhikkhunis. Retrieved 29 December 2017.

- ^ "An Interview with Ajahn Brahm". Alliance for Bhikkhunis. Archived from the original on 26 July 2010. Retrieved 15 May 2013.

- ^ "news". Forestsangha.org. Archived from the original on 12 January 2010. Retrieved 24 January 2010.

- ^ "Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project – Bringing the Bhikkhuni Sangha to the UK. ~ Oxford Ajahn Brahm Monastery ~".

- ^ "Buddhistdoor Article".

- ^ "Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project Nun's Monastery Set to Become a Reality".

- ^ "Buddhist abbot Ajahn Brahm in Singapore: 'Unacceptable' that religion has been so cruel to LGBTIs". Gay Star News. 26 July 2014. Archived from the original on 11 November 2020. Retrieved 26 August 2016.

- ^ Perspectives, American Buddhist (30 July 2014). "Buddhist abbot Ajahn Brahm says that it is 'Unacceptable' that religion has been so cruel to LGBTIQs".

- ^ "Perth Community Donates to Rohingya Refugees in Bangladesh". bswa.org. Retrieved 1 October 2021.

- ^ "SuttaCentral". SuttaCentral.

- ^ Interview with Ajahn Brahm 6 November 2017 Tough Questions to Ajahn Brahm

- ^ [1] "Pāli/Theravada Vinaya"

- ^ "Operated by the Buddhist Society of Western Australia". bodhinyana.org.au. Archived from the original on 3 October 2011. Retrieved 1 October 2011.

- ^ "About Us – Anukampa Bhikkhuni Project".

- ^ "ราชกิจจานุเบกษา เล่ม 123 ตอนที่ 15 ข" (PDF). สำนักนายกรัฐมนตรี. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 March 2016. Retrieved 26 October 2016.

- ^ Perpitch, Nicolas (10 June 2019). "Queens Birthday Honours". ABC News.

Further reading[edit]

- Egan, Colleen (18 June 2001). "Monk caught up in fire and brimstone". The Australian.

- Franklin, Dave (11 May 2003). "Religion with a humorous twist". The Sunday Times. Perth, Australia.

- Horayangura, Nissara [in Venetian] (28 April 2009). "The bhikkhuni question". Bangkok Post. The full transcript from the 28 February 2009 interview is available on Buddhanet.

- Pitsis, Simone (27 July 2002). "Brahm's symphony is the sound of silence". The Australian.

- Ranatunga, D. C. (4 February 2007). "Be good, be happy". Sunday Times (Sri Lanka). 41 (36). ISSN 1391-0531.

- "Few minutes of meditation, good way to start". Sunday Times (Sri Lanka). 41 (40). 4 March 2007. ISSN 1391-0531.

- Ranatunga, D. C. (9 December 2007). "Meeting Ajahn Brahm in a relaxed mood". Sunday Times (Sri Lanka). 42 (28). ISSN 1391-0531.

- Smedley, Tim (3 May 2007). "What HR could learn from Buddhism". People Management. 13 (9): 14. ISSN 1358-6297.

- Wettimuny, Samangie (3 March 2011). "Path to inner happiness". Daily News. Sri Lanka. Archived from the original on 24 August 2011.

External links[edit]

- 1951 births

- Alumni of the University of Cambridge

- Australian Buddhists

- English expatriates in Australia

- Theravada Buddhism writers

- Converts to Buddhism

- English Buddhists

- English Theravada Buddhists

- Theravada Buddhist monks

- Living people

- Nonviolence advocates

- Writers from London

- People educated at Latymer Upper School

- Members of the Order of Australia