Alexander Murdoch Mackay

Alexander Murdoch Mackay | |

|---|---|

Alexander Murdoch Mackay | |

| Personal | |

| Born | 13 October 1849 |

| Died | 4 February 1890 (aged 40) Uganda |

| Religion | Presbyterian |

| Nationality | Scottish |

| Alma mater | University of Edinburgh |

| Occupation | Missionary |

| Signature |  |

Alexander Murdoch Mackay (13 October 1849 – 4 February 1890) was a Scottish Presbyterian missionary to Uganda also known as Mackay of Uganda. After studying math, drafting and other technical subjects at several universities, Mackay, at age twenty-five, decided to dedicate his life to Christian missionary work, and saw this as a great opportunity to put his technical skills to beneficial use. He was assigned to serve in Uganda by the Church Missionary Society in 1876. While serving as a missionary he preformed religious and educational services for the native people of that country, however, his mission was often at risk due to the almost constant tribal wars that surrounded the mission, often instigated by Arab traders and Muslim tribes. During the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition Henry Morton Stanley visited Mackay at the Usambiro mission for a short period where he received aid and local information from him. Mackay worked with David Livingstone and Sir John Kirk to help bring an end to the brutal Arab slave trade in central Africa.

Early life[edit]

Mackay was born on 13 October 1849 in Rhynie, Aberdeenshire, the son of Rev Alexander Mackay LL.D (1813-1895) and his first wife, Margaret Lillie (1825-1865)., Mackay's father was the Free Church minister of his parish. In 1864 he enrolled in the grammar school at Aberdeen.. Mackay was sixteen when his mother died the following year. His early education and training at this time was subsequently largely through his father's efforts. The Mackay family lived in a simple house in the countryside, as his father at that time had not taken residence in a Manse. He was himself once an enthusiastic student, who had developed into a man of marked ability. Inclined towards working around machinery rather than playing with his companions, the younger Mackay was his father's constant companion, especially during his walks to the village forge, gas works, carding mill, and other shops. His father, however, had mixed feelings about his son's worldly interests, hoping that he would instead aspire to a more religious vocation.[1][2][3] Mackay's father was also a member of the Royal Geographical Society and an author whose works included a manual on geography, published in 1861, and those in other related fields.[4]

The Mackay family moved to Edinburgh in 1867.[5] Here he studied at the Free Church Training School for Teachers at Edinburgh, then at the University of Edinburgh.[6] For three years Mackay was set on pursuing engineering, applied mechanics mathematics, and natural philosophy at the university, while his father, however, still did all he could to expand his son's knowledge and involvement in Christianity. He was also learned in Greek, Latin, history, music theory, geometry, and mechanical drawing, and freehand drawing, the latter two subjects of which he received an award form the university's Kensington Department. Thereafter he became the Secretary of the Engineering Society, and taught for three hours each morning at George Watson's College. On Sunday morning he attended church services, and in the afternoon taught Sunday School. Mackay would later intimate about the great benefit he received at the Free Church institution, and expressed his great admiration of the rector there. Dr. Maurice Paterson, of whom he was went on to say, " I owe him much—more than much".[7] In later years, while a missionary in Africa, he further expressed his appreciation of his education and acquired skill in a letter:

" I am so far from thinking that my education has been wasted in coming here, that I only wish I had got double the amount of education, not only in the way of book learning, but also in practical skill. This is a field which offers scope for the highest energies. No man can know enough, and be able to turn his hand to too many things, to be a useful missionary in Central Africa."

— — Mackay letter to his father, Uganda, October 11, 1882.[8]

On November 1, 1873, Mackay continued his education in Germany, in order to study its language in greater depth, feeling that was the first step to becoming acquainted with the abundance of folklore and the customs of that country. While in school in Berlin, Mackay displayed a great aptitude for mechanics, drafting, and other related technical fields. In little time he secured a good position as a draftsman, in the Berliner Union Actien-Gesellschaft, a designer and fabricator of steam engines in Boamit, a suburb of Berlin. Here he invented a steam driven agricultural machine, which earned him a first prize at the Exhibition of Steam-Machines held at Breslau.[9] Mackay often offered his religious knowledge to his fellow workers and associates. While in Germany Mackay became good friends with one of the ministers of the Berlin Cathedral, whom he regarded as a "genuine Christian and man of wide culture", and was always made welcomed at his home. During this time was introduced to some of the leading Christians of Berlin, including persons of great prominence in the church society, events of which he often recorded in his diary.[10] By 1874 Mackay had dedicated his life to Christian missionary work.[11]

Missionary career in Uganda[edit]

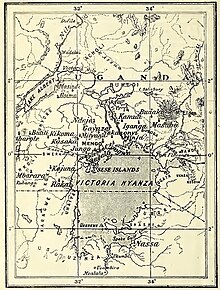

Mackay decided to become a missionary after Henry Morton Stanley was told by King Mutesa I of Buganda that Uganda needed missionaries, and who sent a latter to this effect to The Daily Telegraph in 1875 describing the need and asking for missionaries.[12] [13] At the age of twenty-six, he subsequently joined the Church Missionary Society in 1876, which assigned him to serve in a missionary station in Uganda. Beginning on April 27,1876, he sailed aboard the S.S. Peshawur from Southampton, England, and arrived on the island of Zanzibar on May 30, some fifty miles off the east coast of Tanzania. At Mpwapwa they collected the necessary equipment, and made preliminary plans for their eight-hundred mile trek across Tanzania to the south end of Lake Victoria. On the journey Mackay came down with an acute case of fever and had to return to the coast, carried in a hammock most of the way back to Mpwapwa,[14] while the other members of the party continued on, making their way to the lake, where they put together a vessel, named Daisy, for crossing the lake north to Uganda. After Mackay recovered he organized a labor party and began outfitting a caravan of about seventy loads, and placed it in charge of an Englishman named Morton. In one-hundred days Mackay built a 230 mile wagon road to from Sadani on the coast to Mpwapwa, having to deal with many difficulties through the dense jungle and brush. After everyone had finally regrouped they crossed the lake.to Uganda, arriving there in November 1878.[15][16][17][18]

Once settled in they began their missionary work. Along with preaching the gospel, Mackay taught various skills to the Ugandan people, including carpentry and farming. He was named Muzungu wa Kazi by the Ugandans. The name means "white man of work."[19] A great lover of books, Mackay also kept a library in Uganda containing thousands of books, which also served as sort of a night school for some of the visiting parties.[20][21]- In the period following Mackay's arrival in Uganda the affairs relations between King Metesa and the missionaries were very congenial. The king appeared very anxious to hear more about the Christian religion which had been introduced to him by Stanley.. Mackay subsequently had many a long conversation with the king about the Gospel.[22].

After Mackay had spent a year in Buganda, King Mutesa, having assessed overall matters in relation to the mission more thoroughly, asked Mackay, now a member of the Church Missionary Society, as to what the overall purpose of the missionary might be in his kingdom. Mackay assured the king that that his arrival was in response to the Kabaka's appeal to Stanley. Mutesa, however, was of the understanding that the ulterior reason for their presence was that Kabaka really wanted them to instruct his people how to make powder and guns. Mackay concluded that Mutesa simply regarded all religions as a means to such ends and on that basis he also welcomed the Christian missionaries in the same manner he previously had welcomed Islam, but made it clear that he would turn against Christianity just as readily, if it appeared that their capacity in that country came in conflict with the standards or culture of his kingdom.[23]

The Rev. Robert. P. Ashe, an old friend of Mackay, Bishop Henry Parker and Dr, David Deekes, all of the Church Missionary Society, arrived along with other missionaries, in May 1883. Their arrival was announced with the blowing off of gunpowder and salutations from their Arab companions. The following day they received a warm welcome from Mackay who had brought a donkey for Ashe to ride to the mission. Upon his arrival to the mission he was received by Mackay's fellow-missionary, Rev. P. 0 'Flaherty, who had arrived a month earlier, and showed Ashe his new quarters in a comfortable red brick house which Mackay had built. Ashe later made the first translation of the Book of Common Prayer into the Luganda.language.[24][25] Mackay's technical skills, especially with metal working, amazed many of the natives, who began to ascribe to him mystical powers, sometimes asking him to preform tasks which he could not effect. Such expectations put him in an uncomfortable situation as a Christian, whose position was that only God possessed those qualities, not mortal men.[26]

Mackay established a friendly relationship with Mutesa, but after his death in October 1884, he was pitted with difficulties at the hand of the new king, Mwanga II of Buganda, who despised the progress the Christian mission was making among the people. In October of 1886 Mwanga was becoming increasingly alarmed at the spread of Christianity in about the country. In May he subsequently ordered a general massacre of the Christians, known as the Uganda Martyrs, with many deaths effected as the result of being speared, tortured and roasted alive. So terrorized, the Christians had to flee and go into hiding, abandoning their homes and possessions, while Mwanga continued in his effort for complete removal of Christianity.[27]

Among those martyred was Bishop James Hannington, so ordered by an angry King Mwanga, and whose coming arrival beforehand Mackay had been informed of. Mackay and Ashe, were concerned that the Bishop's arrival arose the worst suspicions of the king and his chiefs, and that it likely would result in bloodshed. Shortly thereafter Mackay received news that the Bishop and his party were taken prisoners and that the king had sent orders to have them all executed. To help keep their minds off the possibility that Hannington and his party were facing execution, Mackay and Ashe kept busy at their printing press, turning out copies of the Gospel of Matthew, with Mackay working on the translation while Ashe was kept busy setting the type. Hoping that he could avert such a decision, Mackay offered to appeal to the king to spare the Bishop's life. Unable to travel because of sickness Mackay sent Ashe with a letter to the king in the hope that this may change the king's decision. Mwanga demanded that if Mackay wanted to have the Bishop and his party 's life's sparred that he would have to come himself. Though feeling very weak, Mackay hurried off to the King's palace at once, but to no avail. Before he had arrived the bishop and his party were martyred.[28]

Opposed to the European and Christian presence in Uganda, Arab traders had befriended the King and were earnestly scheming to drive Christians from Uganda. After much deceptive persuasion,[b] the king definitely declared: “I will not have his (Mackay) teaching in the country while I live." Many white men were compelled to leave Uganda amid all the instability and frequent turmoil. Now that Mackay was alone, the Arabs increased their efforts to drive him from the country. In light of the persecutions that had befallen Christians in Uganda, and that his presence there was now becoming inciteful to this effect, it was decided that it was best if Mackay were to leave Uganda also. In the summer of 1887, after making the necessary arrangements, to arrange for Major-General Charles George Gordon[c] as his replacement, Mackay reluctantly left his home in Uganda. On July 21, 1887 Mackay sailed aboard the Eleanor for Usambrio at the south end of Lake Victoria, 223 miles away, while the King subsequently locked up the mission houses after Mackay had vacated.[31]

As Mackay had worked with Livingstone, Sir John Kirk[d] and Mutesa in bringing an end to the Arab slave trade near Lake Nyanza.[33] the Christian natives were troubled at the prospect of losing their friend and teacher. They feared another time of persecution would occur as soon as Mackay had gone. Mackay, however, gave them assurance that he was not going back to Europe, but only to remain a short time at the south end of the lake.[31][34]

Meanwhile, desperate for power, the Arab traders throughout Central Africa were plotting to assume control and expel the European powers, and in Buganda they were about to attempt a coup d'etat.[35] King Mwanga was now convinced of such an affair occurring from the account given by the Arab traders.[36] When Mwanga's plot to kill Christian and Mohammedan soldiers with starvation by marooning them on a small island on the Lake was discovered he was promptly driven from his throne by the combined effort of those soldiers [37] During the subsequent revolt in the autumn of 1888 Mwanga was driven from his throne and fled for his life with his family and others Mwanga'is successor, Kiweewa of Buganda, regarded the Christians with suspicion. However, Mackay still continued his efforts, maintaining hope of establishing a permanent station, despite all the treachery and conflict that he was surrounded with.[3][35]

Emin Pasha Relief Expedition[edit]

The revolt of Muhammad Ahmad that began in 1881 had cut off Equatoria from the outside world, forcing the Governor, Emin Pasha of Egypt to flee south to Uganda to avoid capture. Here he corresponded with Mackay and others in an effort to procure aid, which ultimately brought the explorer Henry Morton Stanley and the Emin Pasha Relief Expedition to his rescue. During the expedition Stanley met Mackay in 1889 for the first time at the Usambiro mission station when the former was escorting Emin Pasha, the besieged Egyptian governor of Equatoria.[e] and the other refugees back to safety.[38] It was Mackay, through his letter writing, in October 1886, reporting back to England, that provided the first news that Emin Pasha was still alive. Mackay had also corresponded with Emin Pasha, and encouraged him to write letters to Robert Felkin, Consul-General, and Frederick Holmwood a medical missionary in Zanzibar if he thought it best to get England's support. Mackay wrote,

- "The old government at Khartoum no longer exists, but you can deliver over a large territory into English hands, if you wish to do so."

...to which Emin replied..

- "To your question, am I prepared to aid in the annexation of this country by England, I answer frankly "Yes." If England tends to occupy these lands and to civilize them, I am ready to hand over the government into the hands of England, and I believe thereby I should be doing a service to mankind and lending an advance to civilization."[39]

Stanley's visit lasted from August 28 to September 17, and was very pleased with Mackay's seemingly tireless efforts,including the hospitality his party received. Assuming the industrious Mackay was in much need of a rest and a change of station, Stanley urged Mackay to return with him to the coast, but Mackay still chose to remain at his station until his work was completed.[38] Mackay much enjoyed Stanley's company during his short visit, and praised him as a man of "an iron will and sound judgement", and that he was most patient with the natives, never allowing any one of his followers to mistreat, oppress, or even insult them[f] Stanley saw in Mackay "a spirit akin to Livingstone" but was concerned that Mackay was almost at the point of exhaustion and urged him to leave Africa and return to England with him. But Mackay would not abandon his station, and within a half a year had succumbed to fever.[41] He proved very useful to Stanley through his letter writing, providing him with much first-hand information. Stanley would later write that, "Mr. Mackay always writes sensibly. I obtained a great deal of solid information from these letters."[42][g].

Final days and legacy[edit]

Mackay continued to work in Uganda until 1890. Unaware of the pending fever caused by Malaria that would ultimately cause his death,[h] Mackay translated the 14th chapter of the Gospel of John into the Lagunda language.[44] During his last few days at his station in Usambiro, at the south end of Lake Victoria, Mackay began to show the worst symptoms caused by the fever, with Mr. Deeks at his side, who was preparing to return to England because of ill health but decided to stay with Mackay. The care given to Mackay was now left to -*-untrained Waganda Christians who did all they could comfort him and cool his fever.[45] Still more concerned for others, Mackay asked if Stanley and his party had been well provided for. Days later he died on February 4, 1890, 11.00 PM, at the age of 40.[i] A coffin was promptly made using some of the wood Mackay had prepared for the boat, and at two o'clock on the following Sunday Mr. Deekes buried him by the shores of Lake Nyanza (Victoria) which he had always admired. The Baganda Christians and the boys of the village stood around and the grave and sang Gospel hymns.[47][48]

During his missionary service in Uganda and Tanzania Mackay had endured the deaths, from sickness or conflict, of several of his fellow missionaries, including Bishop Hannington, Bishop Parker, and Reverend Blackburn.[49] Despite personal losses and other hardships, he had succeeded in establishing a church that did not diminish during the times of persecution and other tribal unrest, and which continued to grow after his departure.[50] Emin Pasha's gratitude to Mackay for his service to him, Stanley and King Mutesa, and for risking his life and the welfare of the mission, were often expressed by the Pasha to the Khedive of Egypt who posthumously awarded Mackay with the Order of Osmanieh star (pictured).[51][52] Stanley, who had long admired Mackay and his persistent and difficult missionary efforts in Uganda, had often said as much in his letters when he was reporting back to England. Subsequently when they received the news of Mackay's untimely death it "seemed something like a national loss" among the English people.[53]

See also[edit]

- Mackay Memorial College

- William Taylor (missionary) — Renown 19th century Methodist missionary and later Bishop (1889–1896) in South Africa.

- Robert Moffat (missionary) — 19th century missionary in South Africa

- Henry Parker (bishop) — Elevated to Bishop he came to Central Africa to replace the martyred Bishop Harrington in 1886.

- Alfred Tucker -- Bishop of Uganda from 1899 to 1908

Notes[edit]

- ^ Names for towns and villages in 1890 are most often not in use today.

- ^ In a definitive example, Sir John Kirk, who assisted David Livingstone, had sent King Mutesa a letter who instructed one of the Arab traders to translate it for him. They saw this as an opportunity to cast negative aspersions on the missionaries and their purpose in Uganda, and rendered it so.[29]

- ^ Gordon worked with the British and Foreign Anti-Slavery Society, an evangelical Christian group based in London dedicated to ending slavery, and made many such efforts in central Africa.[30]

- ^ From 1858 to 1863 Kirk was Livingstone's chief assistant.[32]

- ^ Equatoria is now part of modern-day South Sudan.

- ^ Mackay also heeded Stanley's former benevolent treatment of the native peoples, which had earned Stanley their respect and assistance during his travels.[40]

- ^ Mackay's last letter to Stanley is dated January 5, 1890, Usambrio.[43]

- ^ Effective treatments for this disease were not available until the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries. See: History of malaria

- ^ Deekes, in a letter of February 12, 1890, informed Mackay's father of his son's death and conveyed the sympathy shared by him and others close to Mackay.[46]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Harrison, 1890, pp.3-6

- ^ Ewing, William Annals of the Free Church

- ^ a b Millar, 1893, p. 118

- ^ Mackay, 1861

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p. 11

- ^ Funk and Wangalls Encyclopedia, 1910, v.7, p. 115

- ^ Harrison, 1890, pp. 12-13

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p. 13

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p. 14

- ^ Melrose, 1893, p. 15

- ^ Ross, 2010

- ^ Harrison, Eugene, 1949, p. 25

- ^ Melrose, 1893, p. 19

- ^ Stock, 1892, p.47

- ^ Harrison, Eugene, 1949, p. 27

- ^ Fahs, 1907, p. 85

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p. 101

- ^ Yule, 1923, p. 50-53

- ^ Fahs, 1907, p. 5

- ^ Stanley, 1890, v. 1, p. 31

- ^ Fahs, 1907, p. 251

- ^ Melrose, 1893, pp. 50-51

- ^ Taylor, 1958, p. 30

- ^ Yule, 1923, p. 167

- ^ Ashe, 1889, p. 46

- ^ Melrose, 1893, p. 51

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p. 468

- ^ Melrose, 1893, pp. 114-116

- ^ Brown, 1892, p. 148

- ^ Urban, 2005, p. 163

- ^ a b Fahs, 1907, pp. 254-255

- ^ McMullen, 2004, p. 771

- ^ Blakie, 1880, p. 464

- ^ Melrose, 1893, pp. 127-128

- ^ a b Taylor, 1958, pp. 57-58

- ^ Mullins, 1904, p. 36

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p. 469

- ^ a b The Religious Tract Society, 10890, p. 14

- ^ Liebowitz & Pearson, 2005, pp. 14-15

- ^ Melrose, 1893, p. 49

- ^ Stanley, 1909, p. 406

- ^ Stanley, 1890, v. 1, p. 31

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p. 467

- ^ Harrison, Eugene, 1949, p. 44

- ^ Fahs, 1907, pp. 267-269

- ^ Harrison, 1890, pp. 472-473

- ^ Harrison, 1890, p.469

- ^ Melrose, 1893, pp. 142-143

- ^ Ashe, 1894, p. 35

- ^ Melrose, 1893, pp. 130-131

- ^ Ashe, 1889, pp. 46-47

- ^ Harrison, 1890, pp. 315-316

- ^ Melrose, 1893, pp. 142-143

Bibliography[edit]

- Ashe, Robert Picjering (1889). Two kings of Uganda, or, Life by the shores of Victoria Nyanza : being an account of a residence of six years in eastern equatorial Africa. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle, & Rivington.

- —— (1894). Chronicles of Uganda. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- Blakie, William Garden (1880). Personal life of David Livingstone, chiefly from his unpublished journals and correspondance in the possession of his family. London: John Murray.

- Brown, Robert (1892). The story of Africa and its explorers. Vol. III. London: Cassell. pp. 146–159, etc.

- Fahs, Sophia Lyon (1907). Uganda's white man of work; a story of Alexander M. Mackay. New York, Young People's Missionary Movement.

- Harrison, Alexina Mackay (1890). A.M. Mackay, pioneer missionary of the Church Missionary Society to Uganda. New York : A. C. Armstrong.

- Harrison, Alexina Mackay Mackay's sister (1898). Mackay of Uganda. The story of the life of Mackay of Uganda. London: Hodder & Stoughton. p. 323.

- Harrison, Eugene Myers (1949). Blazing the missionary trail. Chicago, Illinois: Scripture Press.

- Harrison, Eugene Myers (2010). "Alexander Mackay: Road-Maker for Christ in Uganda". Wholesome Words. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- Liebowitz, Daniel; Pearson, Charles (2005). The Last Expedition: Stanley's Fatal Journey Through the Congo. W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0-39305-9038.

- Mackay, Alexander, Sr. (1861). Manual Of Modern Geography Mathematical Physical And Political. Edinburg and London: William Blackwood & Sons.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - McMullen, Michael D. (2004). Kirk, Sir John Oxford dictionary of national biography : in association with the British Academy : from the earliest times to the year 2000. Vol. XXXI. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 771–772.

- Melrose, Andrew (1893). Alexander MacKay : Missionary hero of Uganda. London: The Sunday School Union.

- Millar, A.H. (1893). Lee, Sidney (ed.). Dictionary of National Biography. Vol. XXXV. London: Smith, Elder & Co. p. 118.

- Mullins, J.D. (1904). The wonderful story of Uganda, to which is added the story of Ham Mukasa, told by himself. London: Church Missionary Society.

- Piroute, M. Losise (1998). Alexander M. Mackay: Biographical dictionary of Christian missions. ISBN 978-0-80284-6808.

- Ross, Stephen (2010). "Alexander Mackay: Chronology of Events". Wholesome Words. Retrieved 10 April 2024.

- Stanley, (Henry Morton (1890). In darkest Africa : or, The quest, rescue and retreat of Emin, governor of Equatoria. Vol. I. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- —— (1890). In darkest Africa : or, The quest, rescue and retreat of Emin, governor of Equatoria. Vol. II. New York: Charles Scribner's Sons.

- —— (1909). The autobiography of Sir Henry Morton Stanley. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

- Stock, Sarah Geraldina (1892). The story of Uganda and the Victoria Nyanza Mission. London: The Religious Tract Society.

- Taylor, John Vernon (1958). Growth of the church in Buganda: an attempt at understanding. London: SCM Press.

- Tucker, Alfred Robert (1911). Eighteen years in Uganda & East Africa. London: Edward Arnold.

- Ward, Kevin. "A History of Christianity in Uganda". Dictionary of African Christian biography. Retrieved 4 April 2024.

- Yule, Mary (1923). Mackay of Uganda; the Missionary Engineer. London: Hodder and Stoughton.

- "The Greatest Missionary since Livingstone", an Address by Professor Anthony Low, at St John the Baptist's Parish Church, Canberra, ACT, 15 October 2000.

- The Schaff-Herzog Encyclopedia of Religious Knowledge. Vol. VII. New York & London: Funk and Wagnalls company. 1910. p. 115.

- The Religious Tract Society (1890). Mackay of Uganda : the story of a consecrated life. London: The Religious Tract Society.

Further reading[edit]

- Beachey, R. W. (1962). "The Arms Trade in East Africa in the Late Nineteenth Century". The Journal of African History. 3 (3): 451. doi:10.1017/s0021853700003352. S2CID 162601116.

- Harrison, Eugene Myers (1949). Blazing the missionary trail. Chicago: Scripture Press, Book Division.

- Mamdani, Mahmood (1984). "Nationality Question in a Neo-Colony: A Historical Perspective". Economic and Political Weekly. 19 (27): 1046–1054. ISSN 0012-9976. JSTOR 4373383.

- Livingstone, David (1874). The last journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to his death : continued by a narrative of his last moments and sufferings, obtained from his faithful servants, Chuma and Susi. Vol. I. London : J. Murray.

- —— (1874). The last journals of David Livingstone in Central Africa, from 1865 to his death : continued by a narrative of his last moments and sufferings, obtained from his faithful servants, Chuma and Susi. Vol. II. London : J. Murray.