Art Spinney

Spinney on a 1954 Bowman football card | |

| No. 81 | |

|---|---|

| Position: | End/Guard |

| Personal information | |

| Born: | November 8, 1927 Saugus, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Died: | May 27, 1994 (aged 66) Lynn, Massachusetts, U.S. |

| Height: | 6 ft 1 in (1.85 m) |

| Weight: | 230 lb (104 kg) |

| Career information | |

| College: | Boston College |

| NFL draft: | 1950 / Round: 15 / Pick: 184 Redrafted 1951, 8th round, 88th overall after termination of Colts franchise. |

| Career history | |

| |

| Career highlights and awards | |

| |

| Career NFL statistics | |

| Player stats at NFL.com · PFR | |

Arthur Franklin Spinney Jr. (November 8, 1927 – May 27, 1994) was an American gridiron football lineman. After a collegiate career at Boston College culminating with his team captaincy in 1949, Spinney played nine professional seasons with the two iterations of the Baltimore Colts of the National Football League (NFL).

Biography[edit]

Early years[edit]

Art Spinney was born November 8, 1927 in Saugus, Massachusetts, where he grew up. He attended Saugus High School, where he won three letters playing end, captaining the team during his senior year.[1]

After leaving Saugus High,[1] Spinney spent 1945 at Manlius Military Academy in DeWitt, New York, playing football for the school squad.[2] World War II came to an end that year, however, altering Spinney's apparent military path.

College career[edit]

Spinney entered Boston College in 1946, with the 190-pound youth quickly gaining attention for his size and speed as an end on the football team.[2] Boston College allowed freshmen on its varsity squad in 1946 and Spinney managed to immediately win a starting position at left end.[1] He sustained a sprained ankle in the opener against Wake Forest, however, briefly forcing him to the sidelines.[3] This would prove to be one of the few times Spinney would be sidelined by injury during his collegiate career, as he would start every game at Boston College during his final three seasons.[1]

Even as a sophomore, Spinney was gaining attention as one of the stars of the Boston College team — a hard blocker on offense and an intelligent and tough defender.[4] Scouts for Louisiana State University called him "cagey" while a local beat sportwriter noted "he is never drawn in on end runs and he hustles every minute he is on the field, whether it be in practice or in a regular game.[4]

At the collegiate level, in an era which players frequently played both offensive and defensive sides of the ball under the single platoon system, Spinney was a stellar performer at end for the run-driven game.

The Boston Globe's Vern Miller explained: "The popular conception rates ends first on pass catching. Every young end is likened to Don Hutson. There are much more primary duties to end play. Art Spinney, BC strong, silent type, is the perfect example of extraordinary defensive player and blocking dynamo, who typifies the coach's dream end. Spinney might not be the best pass receiver that ever climbed The Heights, but at present he is rated by many as the best hunk of football talent..."[5]

Spinney was elected captain of the 1949 Boston College football team.[6]

He ultimately graduated from Boston College with a bachelor's degree in Economics.[7]

Professional career[edit]

Art Spinney was selected by the Baltimore Colts, newcomers from the rival All-America Football Conference (AAFC), in the 15th round of the 1950 NFL Draft, the 184th pick of the draft overall. He was listed at a playing weight of 205 pounds at the time he entered the league.[8] On April 27, he signed a contract with the team paying $5,000[9] — about $78,600 in 2024 terms.

Late in July 1950, while at his rookie training camp with the Colts, Spinney received notice from his local draft board to report for a physical.[10] He was able to begin the 1950 season for the Colts, however.

Spinney's first game action in the green-and-silver uniform of the 1950 Colts came on Sunday, September 17, when the new Baltimore franchise suffered a 38–14 drubbing at the hands of Sammy Baugh and the Washington Redskins. Worse yet, Spinney was knocked from the game with his first reported NFL concussion — one of seven Colts knocked from the contest by injury.[11]

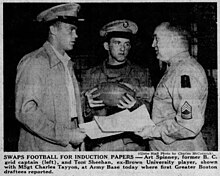

Still feeling the effects of his brain injury on the Monday after his first regular season NFL game, Spinney opened his mail to be hit again, this time with notification to report for induction into the United States Army the following week at Lynn, Massachusetts.[12] Spinney was still able to sneak in one more game before induction, a loss to the Cleveland Browns. He finished his two-game season with 2 receptions for a total of 19 yards gained — the only catches of his career.[13]

The Colts franchise would fold at the end of Spinney's rookie year, but the young end would not be long on the job market, called into military service during the Korean War. Spinney would miss the whole of the 1951 and 1952 NFL seasons as a member of the United States Army Corps of Engineers.[14]

Upon his return for the 1953 season, with the old Colts franchise no more, Spinney reentered the NFL as a free agent, signing with the Cleveland Browns.[15] On March 25, 1953, Spinney was involved in a massive 15 player trade with the new, second version of the Baltimore Colts — a straight 10-for-5 swap of contracts in which no additional money changed hands.[16] Joining Spinney in making the move from the mighty Browns to the expansion Colts were such future starters as defensive backs Don Shula, Bert Rechichar, and Carl Taseff, as well as veteran guard Ed Sharkey.[16]

Later in his pro career, the Colts converted Spinney from defensive end to offensive guard.[15] He increased his playing weight — 205 pounds when he came into the league — to 230 pounds to help him meet the physical challenges of the new position, at which he excelled.[17]

As might be expected playing a grueling line position, Spinney was not immune to injury. He knocked out of action by a torn knee ligament late in October 1957[18] and saw limited minutes for the rest of the year.[13]

In the legendary 1958 NFL Championship game, Spinney found himself matched up against defensive tackle Roosevelt Grier of the New York Giants. Colts quarterback Johnny Unitas later recalled, "Grier complained of being held. On the next play, Art drove Rosey off the line with a tremendous block, then looked at the official and said, 'How was that, Mr. Official?' The official smiled and answered, 'A great block, son, a great block.'"[15]

During the course of his career, Spinney was three times named as a guard to various NFL All-Pro teams — in 1958, 1959, and 1960. He would play eight full seasons in the league after his return from the Korean War, starting in 91 of 93 games played after his return.[13]

Coaching career[edit]

After his career he served as an offensive line coach for the Boston Patriots under Mike Holovak.[19] He was offered a place on the staff with the Miami Dolphins by head coach Don Shula but declined the opportunity, preferring to stay in New England and to start a family.[19]

Life after football[edit]

For a brief time, Spinney worked for the American Biltrite Rubber Company of Cambridge, Massachusetts, as a consultant to its Sports Surfaces Division. In 1972, along with Lawrence J. Warnalis of Medford, Massachusetts, Spinney was awarded a patent for Biltrite's artificial turf product, Poly-Turf, a composite surface for football or soccer fields using additional layers of shock dissipating and shock-absorbing material.[20]

During the last 15 years of his life, Spinney worked in public relations for the Massachusetts Port Authority and then the Massachusetts Department of Transportation.[19]

Death and legacy[edit]

After his playing career, Spinney was plagued by depression and frequent headaches, potentially indicative of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE).[19] He died of a heart attack on May 27, 1994 in Lynn, Massachusetts.[21]

At the time of his death, former Massachusetts Governor Edward J. King, a former college teammate, said of Spinney, "He was the toughest single person I ever encountered, he handed out punishment with clean hard-hitting, but he'd play himself into total fatigue. As an individual, he was one good solid American man."[15]

His Colts teammate Jim Mutscheller said that Spinney "was held in the highest esteem as a player and gentleman. A lot of times, players on the line would forget their assignments on a play but Art would tell them as they headed to the line of scrimmage. He could have played on any team in any era of football."[19]

Spinney was inducted into the Boston College Varsity Club Athletic Hall of Fame in 1972.[6]

Spinney's remains were interred at Riverside Cemetery in Saugus, Massachusetts.[22]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d Baltimore Colts: 1950 Press, Radio, Television Guide, Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Colts, 1950; p. 50.

- ^ a b "Spinney Making Good With B.C." Lynn [MA] Daily Item, Aug. 16, 1946; p. 18.

- ^ "Benedetto May Start for BC at Michigan," Lynn Daily Item, Oct. 3, 1946; p. 13.

- ^ a b "Art Spinney Lauded for End Play," Lynn Daily Item, Oct. 28, 1947; p. 13.

- ^ Vern Miller, "Spinney Rates High on Eagles Eleven," Boston Globe, Sept. 11, 1948; p. 5.

- ^ a b "Art Spinney (1972) - Varsity Club Hall of Fame". Boston College Athletics. Retrieved 2020-01-25.

- ^ Sam Banks (ed.), The Baltimore Colts: 1954 Press, Radio, and TV Guide. Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Colts, 1954; p. 46.

- ^ "Spinney Signs with Colts," Buffalo News, April 27, 1950; p. 17.

- ^ "Greater Boston's First Draft Has Two Football Stars," Boston Daily Globe, Sept. 26, 1950; pp. 1, 39.

- ^ "Spinney Called," Baltimore Evening Sun, July 28, 1950; p. 22.

- ^ James Ellis, "Champ Browns Next for Clem Crowe's Club," Baltimore Evening Sun, Sept. 18, 1950; p. 24.

- ^ U.S. Calls Spinney," Baltimore Evening Sun, Sept. 22, 1950; p. 47.

- ^ a b c "Art Spinney," Pro Football Reference, www.pro-football-reference.com/

- ^ Herb Wright (ed.), Baltimore Colts 1958: Press, Radio, TV Guide. Baltimore, MD: Baltimore Colts, 1958; pp. 36-37.

- ^ a b c d John F. Steadman, "Spinney Was Block of Intensity Colts Came to Admire," Baltimore Sun, June 1, 1994, updated Oct. 24, 2018.

- ^ a b James Ellis, "Colts Acquire Agganis, Nine Others in 15-Player Trade," Baltimore Evening Sun, March 25, 1953, p. 54.

- ^ In 1958 Spinney was named as one of two guards to the "All-Time Colt Team" by Baltimore Colts expert John F. Steadman. See: Steadman, The Baltimore Colts Story. Baltimore: Press Box Publishers, 1958; p. 152.

- ^ Cameron C. Snyder, "DeCarlo Signs Colt Contract," Baltimore Sun, Oct. 31, 1957; p. 29.

- ^ a b c d e Ron Cassie, "Head in the Game: Brain Diseases Have Shortened the Lives of Many of the City's Beloved Former Baltimore Colts. Can Football Survive CTE? Baltimore Magazine, Sept. 2019.

- ^ US 3661687, Spinney Jr., Arthur F. & Warnalis, Lawrence J., "Artificial grass sports field", published 1972-05-09, assigned to American Biltrite Rubber Co. Inc.

- ^ "Sports Log," Boston Globe, May 29, 1994; p. 46.

- ^ "Arthur Franklin “Art” Spinney Jr.," Find a Grave, www.findagrave.com/

Further reading[edit]

- Bill Lambert, "Art Spinney" in George Bozeka (ed.), The 1958 Baltimore Colts: Profiles of the NFL's First Sudden Death Champion. McFarland, 2018.

- 1927 births

- 1994 deaths

- American football offensive linemen

- Baltimore Colts (1947–1950) players

- Baltimore Colts players

- Western Conference Pro Bowl players

- Boston College Eagles football players

- Boston College Eagles football coaches

- Sportspeople from Saugus, Massachusetts

- Boston Patriots (AFL) coaches

- Players of American football from Essex County, Massachusetts

- Sportspeople from Lynn, Massachusetts