Artificial intelligence systems integration

| Part of a series on |

| Artificial intelligence |

|---|

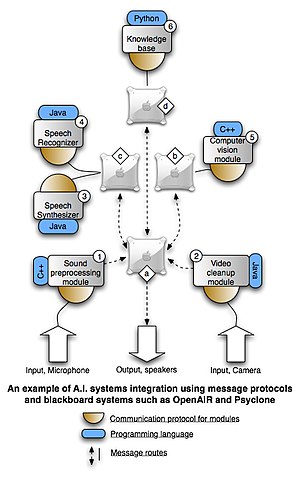

The core idea of artificial intelligence systems integration is making individual software components, such as speech synthesizers, interoperable with other components, such as common sense knowledgebases, in order to create larger, broader and more capable A.I. systems. The main methods that have been proposed for integration are message routing, or communication protocols that the software components use to communicate with each other, often through a middleware blackboard system.

Most artificial intelligence systems involve some sort of integrated technologies, for example, the integration of speech synthesis technologies with that of speech recognition. However, in recent years, there has been an increasing discussion on the importance of systems integration as a field in its own right. Proponents of this approach are researchers such as Marvin Minsky, Aaron Sloman, Deb Roy, Kristinn R. Thórisson and Michael A. Arbib. A reason for the recent attention A.I. integration is attracting is that there have already been created a number of (relatively) simple A.I. systems for specific problem domains (such as computer vision, speech synthesis, etc.), and that integrating what's already available is a more logical approach to broader A.I. than building monolithic systems from scratch.

Integration focus[edit]

The focus on systems' integration, especially with regard to modular approaches, derive from the fact that most intelligences of significant scales are composed of a multitude of processes and/or utilize multi-modal input and output. For example, a humanoid-type of intelligence would preferably have to be able to talk using speech synthesis, hear using speech recognition, understand using a logical (or some other undefined) mechanism, and so forth. In order to produce artificially intelligent software of broader intelligence, integration of these modalities is necessary.

Challenges and solutions[edit]

Collaboration is an integral part of software development as evidenced by the size of software companies and the size of their software departments. Among the tools to ease software collaboration are various procedures and standards that developers can follow to ensure quality, reliability and that their software is compatible with software created by others (such as W3C standards for webpage development). However, collaboration in fields of A.I. has been lacking, for the most part not seen outside the respected schools, departments or research institutes (and sometimes not within them either). This presents practitioners of A.I. systems integration with a substantial problem and often causes A.I. researchers to have to 're-invent the wheel' each time they want a specific functionality to work with their software. Even more damaging is the "not invented here" syndrome, which manifests itself in a strong reluctance of A.I. researchers to build on the work of others.

The outcome of this in A.I. is a large set of "solution islands": A.I. research has produced numerous isolated software components and mechanisms that deal with various parts of intelligence separately. To take some examples:

- Speech synthesis

- FreeTTS from CMU

- Speech recognition

- Sphinx from CMU

- Logical reasoning

- OpenCyc from Cycorp

- Open Mind Common Sense Net from MIT

With the increased popularity of the free software movement, a lot of the software being created, including A.I. systems, is available for public exploit. The next natural step is to merge these individual software components into coherent, intelligent systems of a broader nature. As a multitude of components (that often serve the same purpose) have already been created by the community, the most accessible way of integration is giving each of these components an easy way to communicate with each other. By doing so, each component by itself becomes a module, which can then be tried in various settings and configurations of larger architectures. Some challenging and limitations of using A.I. software is the uncontrolled fatal errors. For example, serious and fatal errors have been discovered in very precise fields such as human oncology, as in an article published in the journal Oral Oncology Reports entitled “When AI goes wrong: Fatal errors in oncological research reviewing assistance".[1] The article pointed out a grave error in artificial intelligence based on GBT in the field of biophysics.

Many online communities for A.I. developers exist where tutorials, examples, and forums aim at helping both beginners and experts build intelligent systems. However, few communities have succeeded in making a certain standard, or a code of conduct popular to allow the large collection of miscellaneous systems to be integrated with any ease.

Methodologies[edit]

Constructionist design methodology[edit]

The constructionist design methodology (CDM, or 'Constructionist A.I.') is a formal methodology proposed in 2004, for use in the development of cognitive robotics, communicative humanoids and broad AI systems. The creation of such systems requires the integration of a large number of functionalities that must be carefully coordinated to achieve coherent system behavior. CDM is based on iterative design steps that lead to the creation of a network of named interacting modules, communicating via explicitly typed streams and discrete messages. The OpenAIR message protocol (see below) was inspired by the CDM and has frequently been used to aid in the development of intelligent systems using CDM.

Examples[edit]

- ASIMO, Honda's humanoid robot, and QRIO, Sony's version of a humanoid robot.

- Cog, M.I.T. humanoid robot project under the direction of Rodney Brooks.

- AIBO, Sony's robot dog, integrates vision, hearing and motorskills.

- TOPIO, TOSY's humanoid robot can play ping-pong with human

See also[edit]

- Hybrid intelligent system, systems that combine the methods of traditional symbolic AI & that of Computational intelligence.

- Neurosymbolic AI

- Humanoid robots utilize systems integration intensely.

- Constructionist design methodology

- Cognitive architectures

References[edit]

- ^ Al-Raeei, Marwan (March 20, 2024). "When AI goes wrong: Fatal errors in oncological research reviewing assistance". Oral Oncology Reports: 100292. doi:10.1016/j.oor.2024.100292. ISSN 2772-9060.

Notes[edit]

- Constructionist Design Methodology, published in A.I. magazine

- MissionEngine: Multi-system integration using Python in the Tactical Language Project