Axes of subordination

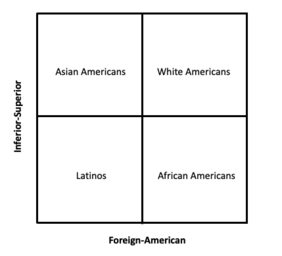

In social psychology, the two axes of subordination is a racial position model that categorizes the four most common racial groups in the United States (Whites, African Americans, Asian Americans, and Latinos) into four different quadrants.[1] The model was first proposed by Linda X. Zou and Sapna Cheryan in the year 2017, and suggests that U.S. racial groups are categorized based on two dimensions: perceived inferiority and perceived cultural foreignness.[1] Support for the model comes from both a target and perceivers perspective in which Whites are seen as superior and American, African Americans as inferior and American, Asian Americans as superior and foreign, and Latinos as inferior and foreign.[1]

U.S. racial hierarchy history[edit]

The United States is a country that was founded on slavery, the dispersion of Native Americans, and the holding of Mexican territories.[2][3] Even after slavery was abolished, the segregation of African Americans continued through Jim Crow laws and Black Codes.[3] The history of the United States led to a racial hierarchy in which Whites are at the top, and Blacks are at the bottom, with all other groups somewhere in between.[4] Although this Black-White model provides an explanation for inequality between White and Black Americans, it is not sufficient in explaining the disadvantage of other racial minorities such as Asian Americans and Latinos.[5]

As the migration of immigrants to the United States became prominent, an increase of Latinos and Asian Americans in the country occurred. The Black-White model explaining racial hierarchy is no longer ideal as it fails to capture the variability of racial minorities. For example, racial minorities vary on numerous factors such as well-being, income, education, and forms of prejudice experienced.[6][7][8][1] The two-axes of subordination takes into consideration racial minority group variability through their two dimensions of perceived inferiority and perceived cultural foreignness.

Need[edit]

Although there are different racial hierarchies, there is a common idea behind all them. That is, the idea that some groups are better than others. It may seem counterintuitive to not treat every group as equal, but previous research demonstrates that there are multiple ways in which racial hierarchies are beneficial. Ultimately, racial hierarchies contribute to the overall success of an organization by allowing cooperation among groups and incentives for improvement among various other factors.[9] Even a hierarchy within groups is also beneficial as groups composed of members with different rankings can perform better on a interdependent task than groups composed of members of equal status.[10]

Two important contributors to the study of group based hierarchies in social psychology are Jim Sidanius and Felicia Pratto. Both proposed social dominance theory in order to explain why societies build and maintain hierarchies on various factors such as race.[11] According to them, one way in which racial hierarchies are maintained is through hiearchy-enhancing legitimising myths, where in stable societies, justify the existing hierarchy.[12] Social dominance theory identifies other factors that help maintain hierarchies such as institutional discrimination, individual discrimination, and intergroup processes such as ingroup bias.[12] Building off social dominance theory, social dominance orientation takes into consideration that individuals vary in terms of how much they support inequality among groups. Individuals who are high on social dominance orientation are supportive of hierarchy enhancing roles and ideologies.[13] The need for racial hierarchy is therefore present at both the group and individual level.

It is well known that group hierarchies benefit those groups with power, but harm those groups who are considered minorities. Knowing this, it is odd that inferior groups justify the existing hierarchy by not fighting back. John T. Jost developed system justification theory to explain why minority groups justify their situation, and in some cases, look up to those who have the power.[14] The theory of system justification proposes that there are various psychological benefits to justifying the system, even among those who are considered to be a part of the minority group. The origin of system justification theory came from many other theories that include social identity theory, the belief in a just world, cognitive dissonance theory, marxist-feminist theories of ideology, and social dominance theory.[15] Individuals who are part of minority groups justify the existing system due to rationalization of the status quo, internalizing of inequality, the reduction of dissonance.[15] It seems that individuals would sometimes rather be stuck in certain discomfort than uncertain pleasantness.

Dimensions[edit]

Inferiority[edit]

One dimension of the two axes of subordination racial position model is perceived inferiority. This category can be best defined as a group's socioeconomic status and racial groups can classify as either inferior or superior under this dimension.[1] The two axes of subordination categorizes White Americans as the superordinate group with the highest status.[1]

Cultural foreignness[edit]

The other dimension of the two axes of subordination racial position model is perceived cultural foreignness. Cultural foreignness gets at the idea that racial groups are perceived to differ in terms of how far away they are from the dominant group.[1] Since the two axes of subordination model focuses on U.S. racial relations, the dominant reference group is White Americans.[1] Racial groups can classify as either foreign or American under this dimension.

Racial minority groups[edit]

White Americans[edit]

- Perceived inferiority: superior

- Perceived cultural foreignness: American

Description: Since the two axes of subordination model focuses on U.S. racial relations, White Americans have the privilege of being high on both dimensions, making them superior and American. Across self reports of experiences of racial prejudice, Whites' most common answer was that they have not experienced racial prejudice and were the least likely to experience prejudice based on inferiority as well.[1] Support for the notion that Whites are high on both dimensions does not only come from self reports of Whites, but also from the perceptions of others. Across perceptions of White Americans from others, Whites are the racial group that are seen as the least inferior and foreign.[1] This perception that Whites are superior and American is nothing new. People associate being American as being White, and across the world, there is a view that leaders are White.[16][17] Being White is so powerful that even multiracials who have White ancestry are considered to be of higher status compared to multiracials that do not have White ancestry.[18] White Americans are in a great position as they are at the top, but it is also an interesting position to be in as they are motivated to stay there. Previous research demonstrates that amongst White Americans, prototypicality threat is reduced if outgroup assimilation is expected when confronted with the loss of a numerical majority.[19] Furthermore, White Americans who perceive a threat to the American culture are less likely to intertwine with growing racial minority groups.[20] As the migration of foreigners (specifically Latinos) to the U.S. continues through the years, it will be interesting to see if Whites are able to remain at the top.

Black Americans[edit]

- Perceived inferiority: inferior

- Perceived cultural foreignness: American

Description: In reference to the two axes of subordination model, Black Americans are low on the inferiority dimension, but high on the cultural foreignness dimension. It is important to remember that being high on cultural foreignness means that you deviate less from the superordinate group, which in this case, is White Americans. This makes Black Americans inferior, but American. Support for this notion comes from self reports of Black Americans who describe their experiences of racial prejudice as based on inferiority rather than from cultural foreignness.[1] From a perceiver's perspective, Black Americans are also perceived to be inferior and American, but not as American as Whites.[1] Although Black Americans are not seen as the same level of American as Whites, they are the only racial minority group, other than Native Americans, that are perceived to be American as opposed to foreign.[1] Because slavery of African Americans has a longstanding history in the United States, it is not surprising that Black Americans are considered American. Black Americans, through slavery, had a tremendous positive impact on the economy of North America.[21] Despite the civil rights movement and all of the modern day progress towards racial equality (e.g., affirmative action) in the United States, Black Americans are still considered inferior. A good indication of this is that there continues to be both a wage and academic gap among Black Americans in the U.S..[22][23] As American psychologist David O. Sears points out, there continues to be a boundary that restricts Black Americans from improving their position, this is known as Black exceptionalism.[24]

Asian Americans[edit]

- Perceived inferiority: superior

- Perceived cultural foreignness: foreign

Description: Asian Americans in the two axes of subordination model are high on the inferiority dimension, but low on cultural foreignness. This makes Asian Americans superior, but foreign. Out of the four major racial groups in the United States, Asian Americans are the only racial minority group to be considered superior. Support for this notion comes from the perspective of the target as well as perceivers.[1] Asian Americans are considered the model minority due to their ability to get into prestigious schools and attain great jobs.[25] The labeling of being the model minority has led Asian Americans to be positively stereotyped. A common belief that individuals hold about Asian Americans is that they are high academic achievers.[26] Although it may seem like a great thing to be stereotyped in a positive way, the labeling of Asian Americans as the model minority can have negative psychological consequences.[27][28] Despite Asian Americans being considered superior and the model minority, they are seen as foreign and continue to experience high amounts of racism.[29] In the midst of the Covid-19 pandemic, Asian American hate increased and was not uncommon.[30][31] So although Asian Americans are highly acknowledged in terms of their superiority, they are still targeted in terms of their foreignness.

Latinos[edit]

- Perceived inferiority: inferior

- Perceived cultural foreignness: foreign

Description: Latinos are in an interesting quadrant in the two axes of subordination racial position model as they are low on both dimensions, making them inferior and foreign. In an interview of White Americans on attitudes toward Latinos, White Americans believe that Latinos are inferior because they have low paying jobs, live in poverty, and commit crime.[32] In Latinos' recall of their experience with racial prejudice, their responses indicate they are stereotyped based on beliefs of inferiority such as low education and class.[1] In addition to being inferior, Latinos are seen as foreign according to Latinos themselves and perceivers of the Latinos.[1] Being low on both dimensions of the racial position model is difficult as Latinos are a target of subordination on two dimensions as opposed to one in contrast to other racial minority groups (e.g., Asian Americans, Black Americans). So although Latino population continues to increase in the United States, their position in the racial position model is low on both dimensions.

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p Zou, Linda X.; Cheryan, Sapna (2017). "Two axes of subordination: A new model of racial position". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 112 (5): 696–717. doi:10.1037/pspa0000080. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 28240941. S2CID 30981264.

- ^ "A Brief History of Racism in the United States and Implications for the Helping Professions", Racism in the United States, New York, NY: Springer Publishing Company, 2021, doi:10.1891/9780826185570.0003, ISBN 978-0-8261-8556-3, S2CID 245469138, retrieved 2022-11-08

- ^ a b Abraham, Peter; Williams, Ellen; Bishay, Anthony E.; Farah, Isabella; Tamayo-Murillo, Dorathy; Newton, Isabel G. (2021-07-01). "The Roots of Structural Racism in the United States and their Manifestations During the COVID-19 Pandemic". Academic Radiology. 28 (7): 893–902. doi:10.1016/j.acra.2021.03.025. ISSN 1076-6332. PMID 33994077. S2CID 234745680.

- ^ Song, Miri (2004-11-01). "Introduction: Who's at the bottom? Examining claims about racial hierarchy". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 27 (6): 859–877. doi:10.1080/0141987042000268503. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 144094881.

- ^ Gold, Steven J. (2004-11-01). "From Jim Crow to racial hegemony: Evolving explanations of racial hierarchy". Ethnic and Racial Studies. 27 (6): 951–968. doi:10.1080/0141987042000268549. ISSN 0141-9870. S2CID 1264748.

- ^ Rohde, Nicholas; Guest, Ross (2013). "Multidimensional Racial Inequality in the United States". Social Indicators Research. 114 (2): 591–605. doi:10.1007/s11205-012-0163-0. ISSN 0303-8300. S2CID 255005776.

- ^ Akee, Randall; Jones, Maggie R.; Porter, Sonya R. (2019-04-03). "Race Matters: Income Shares, Income Inequality, and Income Mobility for All U.S. Races". Demography. 56 (3): 999–1021. doi:10.1007/s13524-019-00773-7. ISSN 0070-3370. PMID 30945204. S2CID 93000145.

- ^ Warikoo, Natasha; Sinclair, Stacey; Fei, Jessica; Jacoby-Senghor, Drew (2016). "Examining Racial Bias in Education: A New Approach". Educational Researcher. 45 (9): 508–514. doi:10.3102/0013189X16683408. ISSN 0013-189X. S2CID 56096350.

- ^ Halevy, Nir; Y. Chou, Eileen; D. Galinsky, Adam (2011). "A functional model of hierarchy: Why, how, and when vertical differentiation enhances group performance". Organizational Psychology Review. 1 (1): 32–52. doi:10.1177/2041386610380991. ISSN 2041-3866. S2CID 146627362.

- ^ Ronay, Richard; Greenaway, Katharine; Anicich, Eric M.; Galinsky, Adam D. (2012). "The Path to Glory Is Paved With Hierarchy: When Hierarchical Differentiation Increases Group Effectiveness". Psychological Science. 23 (6): 669–677. doi:10.1177/0956797611433876. ISSN 0956-7976. PMID 22593117. S2CID 206586088.

- ^ "Social Dominance Theory: A New Synthesis", Social Dominance, Cambridge University Press, pp. 31–58, 1999-07-28, doi:10.1017/cbo9781139175043.002, ISBN 9780521622905, retrieved 2022-11-08

- ^ a b Pratto, Felicia; Sidanius, Jim; Levin, Shana (2006-01-01). "Social dominance theory and the dynamics of intergroup relations: Taking stock and looking forward". European Review of Social Psychology. 17 (1): 271–320. doi:10.1080/10463280601055772. ISSN 1046-3283. S2CID 15052639.

- ^ Pratto, Felicia; Sidanius, Jim; Stallworth, Lisa M.; Malle, Bertram F. (1994). "Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 67 (4): 741–763. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.67.4.741. ISSN 1939-1315.

- ^ Jost, John T.; Andrews, Rick (2011-11-13), "System Justification Theory", The Encyclopedia of Peace Psychology, Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd, doi:10.1002/9780470672532.wbepp273, ISBN 9781405196444, retrieved 2022-11-15

- ^ a b Jost, John; Hunyady, Orsolya (2003). "The psychology of system justification and the palliative function of ideology". European Review of Social Psychology. 13 (1): 111–153. doi:10.1080/10463280240000046. ISSN 1046-3283. S2CID 1328491.

- ^ Devos, Thierry; Banaji, Mahzarin R. (2005). "American = White?". Journal of Personality and Social Psychology. 88 (3): 447–466. doi:10.1037/0022-3514.88.3.447. ISSN 1939-1315. PMID 15740439.

- ^ Logan, Nneka (2011-10-01). "The White Leader Prototype: A Critical Analysis of Race in Public Relations". Journal of Public Relations Research. 23 (4): 442–457. doi:10.1080/1062726X.2011.605974. ISSN 1062-726X. S2CID 143287659.

- ^ Garay, Maria M.; Perry, Jennifer M.; Remedios, Jessica D. (2022-04-28). "The Maintenance of the U.S. Racial Hierarchy Through Judgments of Multiracial People Based on Proximity to Whiteness". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin: 014616722210861. doi:10.1177/01461672221086175. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 35481392. S2CID 248415598.

- ^ Danbold, Felix; Huo, Yuen J. (2022). "Welcome to Be Like Us: Expectations of Outgroup Assimilation Shape Dominant Group Resistance to Diversity". Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin. 48 (2): 268–282. doi:10.1177/01461672211004806. ISSN 0146-1672. PMID 34010075. S2CID 234792510.

- ^ Zou, Linda X.; Cheryan, Sapna (2022). "Diversifying neighborhoods and schools engender perceptions of foreign cultural threat among White Americans". Journal of Experimental Psychology: General. 151 (5): 1115–1131. doi:10.1037/xge0001115. ISSN 1939-2222. PMID 34694861.

- ^ Wright, Gavin (2022-05-01). "Slavery and the Rise of the Nineteenth-Century American Economy". Journal of Economic Perspectives. 36 (2): 123–148. doi:10.1257/jep.36.2.123. ISSN 0895-3309. S2CID 248716718.

- ^ Goldsmith, Arthur H.; Hamilton, Darrick; Darity, William (2007). "From Dark to Light: Skin Color and Wages Among African-Americans". Journal of Human Resources. XLII (4): 701–738. doi:10.3368/jhr.xlii.4.701. ISSN 0022-166X. S2CID 153891263.

- ^ Leach, Monica T.; Williams, Sheara A. (2007-11-29). "The Impact of the Academic Achievement Gap on the African American Family". Journal of Human Behavior in the Social Environment. 15 (2–3): 39–59. doi:10.1300/J137v15n02_04. ISSN 1091-1359.

- ^ Sears, David O.; Savalei, Victoria (2006). "The Political Color Line in America: Many "Peoples of Color" or Black Exceptionalism?". Political Psychology. 27 (6): 895–924. doi:10.1111/j.1467-9221.2006.00542.x. ISSN 0162-895X.

- ^ Hu, Arthur (1989-01-01). "Asian Americans: Model Minority or Double Minority?". Amerasia Journal. 15 (1): 243–257. doi:10.17953/amer.15.1.e032240687706472. ISSN 0044-7471.

- ^ Trytten, Deborah A.; Lowe, Anna Wong; Walden, Susan E. (2012). ""Asians are Good at Math. What an Awful Stereotype" The Model Minority Stereotype's Impact on Asian American Engineering Students". Journal of Engineering Education. 101 (3): 439–468. doi:10.1002/j.2168-9830.2012.tb00057.x. S2CID 144783391.

- ^ Wong, Frieda; Halgin, Richard (2006). "The "Model Minority": Bane or Blessing for Asian Americans?". Journal of Multicultural Counseling and Development. 34 (1): 38–49. doi:10.1002/j.2161-1912.2006.tb00025.x.

- ^ Qin, Desirée Boalian; Way, Niobe; Mukherjee, Preetika (2008). "The Other Side of the Model Minority Story: The Familial and Peer Challenges Faced by Chinese American Adolescents". Youth & Society. 39 (4): 480–506. doi:10.1177/0044118X08314233. ISSN 0044-118X. S2CID 144981669.

- ^ Alvarez, Alvin N.; Juang, Linda; Liang, Christopher T. H. (2006). "Asian Americans and racism: When bad things happen to "model minorities."". Cultural Diversity and Ethnic Minority Psychology. 12 (3): 477–492. doi:10.1037/1099-9809.12.3.477. ISSN 1939-0106. PMID 16881751.

- ^ Tessler, Hannah; Choi, Meera; Kao, Grace (2020-08-01). "The Anxiety of Being Asian American: Hate Crimes and Negative Biases During the COVID-19 Pandemic". American Journal of Criminal Justice. 45 (4): 636–646. doi:10.1007/s12103-020-09541-5. ISSN 1936-1351. PMC 7286555. PMID 32837158.

- ^ Han, Sungil; Riddell, Jordan R.; Piquero, Alex R. (2022-06-03). "Anti-Asian American Hate Crimes Spike During the Early Stages of the COVID-19 Pandemic". Journal of Interpersonal Violence. 38 (3–4): 3513–3533. doi:10.1177/08862605221107056. ISSN 0886-2605. PMC 9168424. PMID 35657278.

- ^ Lacayo, Celia Olivia (2017). "Perpetual Inferiority: Whites' Racial Ideology toward Latinos". Sociology of Race and Ethnicity. 3 (4): 566–579. doi:10.1177/2332649217698165. ISSN 2332-6492. S2CID 148722712.