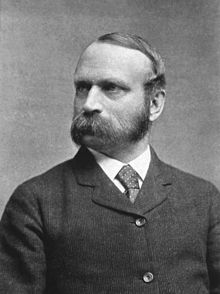

Charles F. Chandler

Charles F. Chandler | |

|---|---|

Charles F. Chandler | |

| Born | December 6, 1836 |

| Died | August 25, 1925 (aged 88) |

| Nationality | American |

| Alma mater | Lawrence Scientific School, University of Göttingen |

| Known for | Chemical Education, Founding the American Chemical Society |

| Awards | Gold Medal of the National Institute of Social Sciences Perkin Medal (1920) |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Industrial Chemistry, Public Health |

| Institutions | Union College, Columbia University |

| Doctoral advisor | Friedrich Wöhler |

| Signature | |

Charles Frederick Chandler (December 6, 1836 – August 25, 1925) was an American chemist, best known for his regulatory work in public health, sanitation, and consumer safety in New York City, as well as his work in chemical education—first at Union College and then, for the majority of his career, at Columbia University, where he taught in the Chemical Department, the College of Physicians and Surgeons, and served as the first Dean of Columbia University's School of Mines.

Early life[edit]

Charles Frederick Chandler was born in Lancaster, Massachusetts, on December 6, 1836. His family moved shortly after his birth to New Bedford, Massachusetts, where he spent most of his formative years and engaged in his earliest formal education. As a child he devoted nearly all of his free time to scientific and geological explorations and attending public lectures on scientific subjects. These public lectures at the New Bedford Lyceum, and in particular a series of lectures given by the geologist and naturalist Louis Agassiz, sparked his lifelong interest in science.[1] He was particularly interested in mineralogy and collected rock and mineral samples that he found around his grandfather's Lancaster home.

Upon completion of his studies at New Bedford High School, Chandler spent a year in private study, learning Latin and Greek and conducting chemical experiments in a laboratory he set up in his father's attic to prepare himself for more advanced chemical study. He then left his home in New Bedford and enrolled in the Lawrence Scientific School of Harvard University. While at Harvard he studied Industrial Chemistry, but he was encouraged to continue his studies in Industrial Chemistry and Geology in Germany, which was at the forefront of scientific education at the time. He enrolled in the University of Göttingen in 1854 to study with Friedrich Wöhler, and after studying under Wöhler and working as an assistant in the lab of Heinrich Rose, the father of analytic chemistry, he earned his PhD from the University of Göttingen in 1856.[1]

Academic career[edit]

After completing his degree, Chandler returned to the United States to pursue his own scientific career. Upon his return, in 1857, Chandler became the chemical assistant at Professor Charles Joy's laboratory at Union College in Schenectady, New York, and shortly thereafter began to lecture on Mineralogy and Geology at the college as well as manage the laboratory. He became an associate professor at the College in 1857 at the age of 21. Shortly after, he and his younger brother William became members of The Kappa Alpha Society, of which Joy was also a member. He remained at Union College for the next 7 years during which time he ran the chemistry lab and married his first wife, Anna Craig Chandler.

His tenure at Union College ended in 1864 when Chandler was asked by his former colleague, Professor Joy, to consider taking on the Chair of Chemistry at the newly formed Columbia College School of Mines that Professor Thomas Egleston and General Vinton were attempting to start under Columbia President Barnard. Chandler gladly took the opportunity to move to New York, and begin his long relationship with Columbia University.

The School of Mines, later to develop into the School of Engineering and Applied Science, consisted at this time of one room in the basement of a Madison Avenue academic building. Within the first year of the School's existence, Chandler took on the position of Dean, and under his leadership in that first year the school moved to a larger four floor building and doubled the number of students enrolled in its program of study. Chandler was to remain dean of the School of Mines for the next 33 years, through its move to its new home on Columbia's Morningside Campus and into Havemeyer Hall, the state-of-the-art Chemistry building that he helped to design and raise funds.

During the period he was the organizer of the American Chemical Society and its president from 1881 to 1889.

Though he stepped down as the dean of the School of Mines in 1897, he continued to teach chemistry at Columbia University until 1910, and proved to be an extremely popular and engaging instructor. One of his former pupils provided the testimony that "He was the most popular professor at Columbia for the forty-seven years he was active. This was due to his ability to place himself on a level and equality with his hearers, or indeed anyone he met... He was a child among children, a man of science among scientific men, but more particularly, he was a real man among his fellow men." This sentiment is echoed in the Columbia College Jester piece that commemorates him upon his retirement, "Year after year he has taken the entering classes by the hand and led them through a course of Chemistry, Ethics, and Humor so cleverly combined that it has made men of them.[2]"

Though Chandler is perhaps most associated with the School of Mines, he also, starting in 1867, began lecturing in Chemistry for the New York College of Pharmacy. He acted as president of this school until 1897 when it formalized its relationship to Columbia University and was incorporated as a University Faculty in 1897. He also lectured in Columbia's College of Physicians and Surgeons in 1872 where he taught chemistry and medical jurisprudence and called for a more rigorous scientific training for medical professionals.[3] In addition to his instructional and administrative duties, Chandler also started a Chemical Museum, later named the Chandler Chemical Museum in his honor, to highlight the accomplishments of modern industrial and analytic chemistry.

While Chandler was a very popular instructor, he was not always so popular among his colleagues. He spent much of his time acting as an expert witness in various legal cases and patent disputes, and performed independent consulting work for companies such as Standard Oil. Many of Chandler's colleagues had concerns that Chandler was more focused on his profitable, outside consulting work than he was on his academic and administrative duties.

Though he was not entirely without controversy, Chandler remained an integral part chemical education at Columbia University until 1911 when he finally, after 46 years of service at Columbia and 54 years of college teaching, retired from teaching. Upon retirement he and his second wife Augusta Berard Chandler continued to reside in New York City, but spent more and more time at their summer home in Westhampton and at her family's home in New Hartford, Connecticut, where Chandler died in 1925.

New York Metropolitan Board of Health[edit]

While chemical instruction made up much of Charles Chandler's career, he was also an energetic public health advocate and sanitation reformer. His career in public service began in 1866 when the Secretary of the Metropolitan Board of Health asked Chandler to perform some chemical work for the board, ex officio. The Board soon realized the value of having a chemist as part of the organization and later that year Chandler was appointed as chemist to the Board of Health. In 1873 Mayor Havemeyer appointed Chandler to the Presidency of the Metropolitan Board of Health, a position he held until 1883.

His work with the New York City Municipal Board of Health led to a number of important sanitary reforms in the city. When he began his services on the Board of Health in 1866, 53 out of every 100 deaths in the city were children under the age of 5. He implemented major reforms to improve infant nutrition, including stopping the sale of watered-down milk, and instituted a corps of traveling physicians to tend to the residents of tenements. By the time he left the board, the child mortality rate had fallen to 46 out of every 100 deaths, an estimated saving of 8000 lives and 5000 children per annum.[3] He was a strong advocate for tenement reform, designing tenement houses that were cleaner and brighter than those most prevalent in the city, and pushing a "Tenement House Act" through legislature.[1] This is all in addition to the more mundane tasks of testing household goods such as cosmetics, patent medicine, and wallpaper for toxic and potentially harmful additives. The Board of Health, under his leadership is credited with preventing a cholera epidemic in 1883. He, himself, thought his most important work with the Board of Health was his work in reducing fatal kerosene related accidents through informing the public about the dangers of kerosene with naphtha and gasoline added (making combustible vapors).[3] All in all, Chandler's leadership of the Board of Health marks an important chapter in the history of sanitation in New York, and his improvements were achieved against political corruption and business interests.[4]

Professional activities and honors[edit]

Chandler was very active in professional and social organizations, belonging to several Chemical Clubs and Organizations. While some of his clubs were purely or primarily social, other such as The Chemists' Club, which Chandler founded, were intended to build professional connections among scientists in New York. He also founded the American Chemical Society, and served twice as its president, first in 1881 and again in 1889. He was the president of both the American Section of the Society of Chemical Industry in New York, and in 1899 became the first American president of the parent association, the Society of Chemical Industry in London.[5][6][7] In 1870 he and his brother William Henry Chandler, a chemistry professor at Lehigh University, started the journal The American Chemist, the first chemical journal in America. They both edited the journal until it was discontinued in 1877.[8]

He received a number of honorary degrees (such as an MD from University of New York and LL.D. from Union College),[9] the Gold Medal of the National Institute of Social Sciences, and the prestigious Perkin Medal from the American Section of the Society of Chemical Industry. After he retired from Columbia University, the alumni of that University set up an endowment for the Chandler lectureship and the Chandler Medal in his honor.

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c "Looking Backward: A Chat with Professor Charles Frederick Chandler by 'Quip'" Medical Quip; January, 1923; Charles F. Chandler Papers; Box 6 folder 4; Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library.

- ^ Columbia University Jester, page 120; Charles F. Chandler Papers; Box 6 folder 4; Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library.

- ^ a b c Typescript Autobiography; Charles F. Chandler Papers, Box 6, folder 3; Rare Book & Manuscript Library, Columbia University Library.

- ^ Florman, Samuel C. (1994). The existential pleasures of engineering. New York: St. Martin's Press. p. 20. ISBN 9780285643727.

- ^ https://www.soci.org/about-us/history/sci-presidents

- ^ "Meeting of Industrial Chemists". American Druggist and Pharmaceutical Record. 37: 82–83. 1900. Retrieved 22 August 2016.

- ^ Bowden, Mary Ellen; Smith, John Kenly (1994). American chemical enterprise : a perspective on 100 years of innovation to commemorate the centennial of the Society of Chemical Industry (American Section). Philadelphia: Chemical Heritage Foundation. p. 10. ISBN 9780941901130.

- ^ Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ Scientific American. Munn & Company. 1887-07-16. p. 40.

External links[edit]

- Charles F. Chandler Papers at the Rare Book & Manuscript Library at Columbia University

- Society of Chemical Industry: at www.soci.org

- 100 Years of History in Havemeyer at www.Columbia.edu

- http://books.nap.edu/html/biomems/cchandler.pdf

- National Academy of Sciences Biographical Memoir

- Charles Frederick Chandler architectural records and papers collection, 1876-1896. Held by the Department of Drawings & Archives, Avery Architectural & Fine Arts Library, Columbia University.

- 1836 births

- 1925 deaths

- Harvard John A. Paulson School of Engineering and Applied Sciences alumni

- American chemists

- University of Göttingen alumni

- Columbia School of Engineering and Applied Science alumni

- Columbia School of Engineering and Applied Science faculty

- Columbia University faculty

- People from Lancaster, Massachusetts

- People from Westhampton, New York

- Members of the American Philosophical Society

- Scientists from New York (state)

- Commissioners of Health of the City of New York