Dorothy Hodgkin

Dorothy Hodgkin | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | Dorothy Mary Crowfoot 12 May 1910 |

| Died | 29 July 1994 (aged 84) Ilmington, Warwickshire, England |

| Nationality | British |

| Education | Sir John Leman Grammar School |

| Alma mater | |

| Known for |

|

| Spouse | |

| Children | 3 |

| Parent(s) | John Winter Crowfoot Grace Mary Hood |

| Awards |

|

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Biochemistry X-ray crystallography |

| Thesis | X-ray crystallography and the chemistry of the sterols (1937) |

| Doctoral advisor | John Desmond Bernal[2] |

| Doctoral students | |

| Other notable students |

|

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin OM FRS HonFRSC[10][11] (née Crowfoot; 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994) was a Nobel Prize-winning English chemist who advanced the technique of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of biomolecules, which became essential for structural biology.[10][12]

Among her most influential discoveries are the confirmation of the structure of penicillin as previously surmised by Edward Abraham and Ernst Boris Chain; and mapping the structure of vitamin B12, for which in 1964 she became the third woman to win the Nobel Prize in Chemistry. Hodgkin also elucidated the structure of insulin in 1969 after 35 years of work.[13]

Hodgkin used the name "Dorothy Crowfoot" until twelve years after marrying Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, when she began using "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". Hodgkin is referred to as "Dorothy Hodgkin" by the Royal Society (when referring to its sponsorship of the Dorothy Hodgkin fellowship), and by Somerville College. The National Archives of the United Kingdom refer to her as "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin".

Early life[edit]

Dorothy Mary Crowfoot was born in Cairo, Egypt,[14] the oldest of the four daughters whose parents worked in North Africa and the middle East in the colonial administration and later as archaeologists. Dorothy came from a distinguished family of archaeologists.[15] Her parents were John Winter Crowfoot (1873–1959), working for the country's Ministry of Education, and his wife Grace Mary (née Hood) (1877–1957), known to friends and family as Molly.[16] The family lived in Cairo during the winter months, returning to England each year to avoid the hotter part of the season in Egypt.[17]

In 1914, Hodgkin's mother left her (age 4) and her two younger sisters Joan (age 2) and Elisabeth (age 7 months) with their Crowfoot grandparents near Worthing, and returned to her husband in Egypt. They spent much of their childhood apart from their parents, yet they were supportive from afar. Her mother would encourage Dorothy to pursue the interest in crystals first displayed at the age of 10. In 1923, Dorothy and her sister would study pebbles that they had found nearby streams using portable mineral analysis kit. Their parents then moved south to Sudan where, until 1926, her father was in charge of education and archaeology. Her mother's four brothers were killed in World War I and as a result she became an ardent supporter of the new League of Nations.[18][19]

In 1921 Hodgkin's father entered her in the Sir John Leman Grammar School in Beccles, England,[11] where she was one of two girls allowed to study chemistry.[20] Only once, when she was 13, did she make an extended visit to her parents, then living in Khartoum, the capital of Sudan, where her father was Principal of Gordon College. When she was 14, her distant cousin, the chemist Charles Harington (later Sir Charles), recommended D. S. Parsons' Fundamentals of Biochemistry.[21] Resuming the pre-war pattern, her parents lived and worked abroad for part of the year, returning to England and their children for several months every summer. In 1926, on his retirement from the Sudan Civil Service, her father took the post of Director of the British School of Archaeology in Jerusalem, where he and her mother remained until 1935.[22]

In 1928, Hodgkin joined her parents at the archaeological site of Jerash, in present-day Jordan, where she documented the patterns of mosaics from multiple Byzantine-era Churches dated to the 5th–6th centuries. She spent more than a year finishing the drawings as she started her studies in Oxford, while also conducting chemical analyses of glass tesserae from the same site.[23] Her attention to detail through the creation of precise scale drawings of these mosaics mirrors her subsequent work in recognising and documenting patterns in chemistry. Hodgkin enjoyed the experience of field archaeology so much that she considered giving up chemistry in favour of archaeology.[24] Her drawings are archived by Yale University.[15]

Hodgkin developed a passion for chemistry from a young age, and her mother, a proficient botanist, fostered her interest in the sciences. On her 16th birthday her mother gave her a book by W. H. Bragg on X-ray crystallography, "Concerning the Nature of Things", which helped her decide her future.[25] She was further encouraged by the chemist A.F. Joseph, a family friend who also worked in Sudan.[26]

Her state school education did not include Latin, then required for entrance to Oxbridge. Her Leman School headmaster gave her personal tuition in the subject, enabling her to pass the University of Oxford entrance examination.[citation needed]

When Hodgkin was asked in later life to name her childhood heroes, she named three women: first and foremost, her mother, Molly; the medical missionary Mary Slessor; and Margery Fry, the Principal of Somerville College.[27]

Higher education[edit]

In 1928 at age 18 Hodgkin entered Somerville College, Oxford, where she studied chemistry.[26] She graduated in 1932 with a first-class honours degree, the third woman at this institution to achieve this distinction.[28]

In the autumn of that year, she began studying for a PhD at Newnham College, Cambridge, under the supervision of John Desmond Bernal.[29] It was then that she became aware of the potential of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of proteins. She was working with Bernal on the technique's first application to the analysis of a biological substance, pepsin.[30] The pepsin experiment is largely credited to Hodgkin, however she always made it clear that it was Bernal who initially took the photographs and gave her additional key insights.[31] Her PhD was awarded in 1937 for research on X-ray crystallography and the chemistry of sterols.[2]

Career and discoveries[edit]

In 1933 Hodgkin was awarded a research fellowship by Somerville College, and in 1934, she moved back to Oxford. She started teaching chemistry with her own lab equipment. The college appointed her its first fellow and tutor in chemistry in 1936, a post which she held until 1977. In the 1940s, one of her students was Margaret Roberts (later Margaret Thatcher)[32] who, while Prime Minister, hung a portrait of Hodgkin in her office at Downing Street out of respect for her former teacher.[26] Hodgkin was, however a life-long Labour Party supporter.[33]

In April 1953, together with Sydney Brenner, Jack Dunitz, Leslie Orgel, and Beryl M. Oughton, Hodgkin was one of the first people to travel from Oxford to Cambridge to see the model of the double helix structure of DNA, constructed by Francis Crick and James Watson, which was based on data and technique acquired by Maurice Wilkins and Rosalind Franklin. According to the late Dr Beryl Oughton (married name, Rimmer), they drove to Cambridge in two cars after Hodgkin announced that they were off to see the model of the structure of DNA.

Hodgkin became a reader at Oxford in 1957 and she was given a fully modern laboratory the following year.[34] In 1960, Hodgkin was appointed the Royal Society's Wolfson Research Professor, a position she held until 1970.[35] This provided her salary, research expenses and research assistance to continue her work at the University of Oxford. She was a fellow of Wolfson College, Oxford, from 1977 to 1983.[36]

Steroid structure[edit]

Hodgkin was particularly noted for discovering three-dimensional biomolecular structures.[12] In 1945, working with C.H. (Harry) Carlisle, she published the first such structure of a steroid, cholesteryl iodide (having worked with cholesteryls since the days of her doctoral studies).[37]

Penicillin structure[edit]

In 1945, Hodgkin and her colleagues, including biochemist Barbara Low, solved the structure of penicillin, demonstrating, contrary to scientific opinion at the time, that it contains a β-lactam ring. The work was not published until 1949.[38][nb 1]

Vitamin B12 structure[edit]

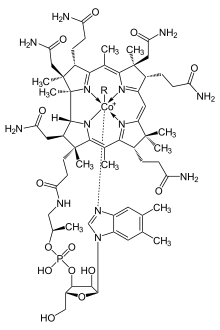

In 1948, Hodgkin first encountered vitamin B12,[39] one of the most structurally complex vitamins known, and created new crystals. Vitamin B12 had first been discovered at Merck earlier that year. It had a structure at the time that was almost completely unknown, and when Hodgkin discovered it contained cobalt, she realized the structure actualization could be determined by X-ray crystallography analysis. The large size of the molecule, and the fact that the atoms were largely unaccounted for—aside from cobalt—posed a challenge in structure analysis that had not been previously explored.[40]

From these crystals, she deduced the presence of a ring structure because the crystals were pleochroic, a finding which she later confirmed using X-ray crystallography. The B12 study published by Hodgkin was described by Lawrence Bragg as being as significant "as breaking the sound barrier".[40][41] Scientists from Merck had previously crystallised B12, but had published only refractive indices of the substance.[42] The final structure of B12, for which Hodgkin was later awarded the Nobel Prize, was published in 1955[43] and 1956.[44]

Insulin structure[edit]

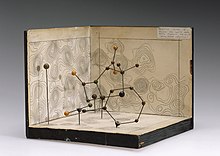

Insulin was one of Hodgkin's most extraordinary research projects. It began in 1934 when she was offered a small sample of crystalline insulin by Robert Robinson. The hormone captured her imagination because of the intricate and wide-ranging effect it has in the body. However, at this stage X-ray crystallography had not been developed far enough to cope with the complexity of the insulin molecule. She and others spent many years improving the technique.

It took 35 years after taking her first photograph of an insulin crystal for X-ray crystallography and computing techniques to be able to tackle larger and more complex molecules like insulin. Hodgkin's dream of unlocking the structure of insulin was put on hold until 1969 when she was finally able to work with her team of young, international scientists to uncover the structure for the first time. Hodgkin's work with insulin was instrumental in paving the way for insulin to be mass-produced and used on a large scale for treatment of both type one and type two diabetes.[45] She went on to cooperate with other laboratories active in insulin research, giving advice, and traveling the world giving talks about insulin and its importance for the future of diabetes. Solving the structure of insulin had two important implications for the treatment of diabetes, both making mass production of insulin possible and allowing scientists to alter the structure of insulin to create even better drug options for patients going forward.[45]

Personal life[edit]

Personality[edit]

Hodgkin's soft-spoken, gentle and modest demeanor hid a steely determination to achieve her ends, whatever obstacles might stand in her way. She inspired devotion in her students and colleagues, even the most junior of whom knew her simply as Dorothy. Her structural studies of biologically important molecules set standards for a field that was very much in development during her work life. She made fundamental contributions to the understanding of how these molecules carry out their tasks in living system.

Mentor[edit]

Hodgkin's mentor Professor John Desmond Bernal greatly influenced her life: scientifically, politically, and personally. Bernal was a key scientific adviser to the UK government during the Second World War. He was also an open and vocal member of the Communist Party and a faithful supporter of the Soviet regime until its invasion of Hungary in 1956. He is a chemist who believed in equal opportunity for women. In his laboratory, Hodgkin extended work that he began on biological molecules including sterols. She helped him to make the first X-ray diffraction studies of pepsin and crystalline protein. Hodgkin always referred to him as "Sage". They were lovers before she met Thomas Hodgkin.[46] The marriages of both Dorothy and Bernal were unconventional by the standards of the present and of those days.[47]

Health[edit]

In 1934, at the age of 24, Dorothy began experiencing pain in her hands causing them to become swollen and distorted. She was diagnosed with rheumatoid arthritis, and went to a clinic in Buxton for thermal baths and gold treatments.[48] After some treatment, Hodgkin returned to the lab, where she struggled to use the main switch on the x-ray equipment due to the condition of her hands. She had to create a lever on her own in order to utilize the switch.[49] Her condition would become progressively worse and crippling over time, with deformities in both her hands and feet, and prolonged periods of pain. While Hodgkin spent a great deal of time in a wheelchair in her later years, she remained scientifically active in her career.[50]

Marriage and family[edit]

In 1937, Dorothy Crowfoot married Thomas Lionel Hodgkin, an historian's son, who was then teaching an adult-education class in mining and industrial communities in the north of England after he resigned from the Colonial Office.[51] He was an intermittent member of the Communist Party and later wrote several major works on African politics and history, becoming a well-known lecturer at Balliol College in Oxford.[52] As his health was too poor for active military service, he continued working throughout World War II, returning to Oxford on the weekends, where his wife remained working on penicillin. The couple had three children: Luke[53] (b. 1938. d. Oct. 2020), Elizabeth[54] (b. 1941) and Toby[55] (b. 1946). The oldest son, Luke, became a mathematics instructor at the new University of Warwick. Their daughter, Elizabeth, followed her father's career as a historian. Their younger son, Toby, studied botany and agriculture. Overall, Thomas Hodgkin spent extended periods of time in West Africa, where he was enthusiastic supporter and chronicler of the emerging postcolonial states.

Aliases[edit]

Hodgkin published as "Dorothy Crowfoot" until 1949, when she was persuaded by Hans Clarke's secretary to use her married name on a chapter she contributed to The Chemistry of Penicillin. By then she had been married for 12 years, given birth to three children and been elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS).[56]

Thereafter she would publish as "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin", and this was the name used by the Nobel Foundation in its award to her and the biography it included among other Nobel Prize recipients;[56] it is also what the Science History Institute calls her.[57][58] For simplicity's sake, Hodgkin is referred to as "Dorothy Hodgkin" by the Royal Society, when referring to its sponsorship of the Dorothy Hodgkin fellowship,[59] and by Somerville College, after it inaugurated the annual lectures in her honour.

The National Archives of the United Kingdom refer to her as "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin"; on a variety of plaques commemorating places where she worked or lived, e.g. 94 Woodstock Road, Oxford, she is "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". In 2022, the Department of Biochemistry in Oxford renamed its much expanded building after Hodgkin, calling it the "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin Building".[60]

Contacts with scientists abroad[edit]

Between the 1950s and the 1970s, Hodgkin established and maintained lasting contacts with scientists in her field abroad—at the Institute of Crystallography in Moscow; in India; and with the Chinese group working in Beijing and Shanghai on the structure of insulin.

Her first visit to China was in 1959. Over the next quarter century, she travelled there seven more times, the last visit a year before her death.[61] Particularly memorable was the visit in 1971 after the Chinese group themselves independently solved the structure of insulin, later than Hodgkin's team but to a higher resolution. During the subsequent three years, 1972–1975, when she was President of the International Union of Crystallography she was unable to persuade the Chinese authorities, however, to permit the country's scientists to become members of the Union and attend its meetings.

Her relations with a supposed scientist in another "People's Democracy" had less happy results. At the age of 73, Hodgkin wrote a foreword to the English edition of Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene, published by Robert Maxwell as the work of Elena Ceaușescu, wife of Romania's communist dictator. Hodgkin wrote of the author's "outstanding achievements" and "impressive" career.[62] Following the overthrow of Ceausescu during the Romanian Revolution of 1989, it was revealed that Elena Ceausescu had neither finished secondary school nor attended university. Her scientific credentials were a hoax, and the publication in question was written for her by a team of scientists to obtain a fraudulent doctorate.[63]

Political views and activities[edit]

Because of Hodgkin's political activities, and her husband's association with the Communist Party, she was banned from entering the US in 1953 and subsequently not allowed to visit the country except by CIA waiver.[64]

In 1961 Thomas became an advisor to Kwame Nkrumah, President of Ghana, a country he visited for extended periods before Nkrumah's ouster in 1966. Hodgkin was in Ghana with her husband when they received the news that she had been awarded the Nobel Prize.

She acquired from her mother, Molly, a concern about social inequalities and a determination to do what she could to prevent armed conflict. Dorothy became particularly concerned about the threat of nuclear war. In 1976, she became president of the Pugwash Conference and served longer than any who preceded or succeeded her in this post. She stepped down in 1988, the year after the Intermediate-Range Nuclear Forces Treaty imposed "a global ban on short- and long-range nuclear weapons systems, as well as an intrusive verification regime".[4] She accepted the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet government in 1987 in recognition of her work for peace and disarmament.

Disability and death[edit]

Due to distance, Hodgkin decided not to attend the 1987 Congress of the International Union of Crystallography in Australia. However, despite increasing frailty, she astounded close friends and family by going to Beijing for the 1993 Congress, where she was welcomed by all.

She died in July 1994 after a stroke, at her husband's home in the village of Ilmington, near Shipston-on-Stour, Warwickshire.[13]

Portraits[edit]

The National Portrait Gallery, London lists 17 portraits of Dorothy Hodgkin[65] including an oil painting of her at her desk by Maggi Hambling[66] and a photograph portrait by David Montgomery.[67]

Graham Sutherland made preliminary sketches for a portrait of Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin in 1978. One sketch is in the collection of the Science History Institute and another at the Royal Society in London. The portrait was never finished.[58][68][69]

A portrait of Dorothy Hodgkin by Bryan Organ was commissioned by private subscription to become part of the collection of the Royal Society. Accepted by the president of the society on 25 March 1982, it was the first portrait of a woman Fellow to be included in the Society's collection.[70][71]

Honours and awards[edit]

While living[edit]

- By 1945 she had succeeded in identifying the structure of vitamin B12, describing the arrangement of its atoms in three dimensions.

- Hodgkin won the 1964 Nobel Prize in Chemistry, and is the only British woman scientist to have been awarded a Nobel Prize in any of the three sciences it recognizes.

- In 1965 she was appointed to the Order of Merit. She was the second woman to receive the Order.

- In 1976, she was the first woman to receive the prestigious Copley Medal.

- In 1947, she was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1947[72] and EMBO Membership in 1970., Hodgkin was Chancellor of the University of Bristol from 1970 to 1988 which she was given an honorary Degree of Science from University of Bath in 1978.

- In 1958, she was elected a Foreign Honorary Member of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences.[73]

- In 1966, she was awarded the Iota Sigma Pi National Honorary Member for her significant contribution.[74]

- She became a foreign member of the USSR Academy of Sciences in the 1970s.

- In 1982 she received the Lomonosov Medal of the Soviet Academy of Sciences.

- In 1987 she accepted the Lenin Peace Prize from the government of Mikhail Gorbachev and the first woman to receive the copley medal from winning from Lenin Peace Prize.

- An asteroid (5422) discovered on 23 December 1982 by L.G. Karachkina (at the Crimean Astrophysical Observatory, M.P.C. 22509, in the USSR) in 1993 was named "Hodgkin" in her honour.[75]

- In 1983, Hodgkin received the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art.[76]

Legacy[edit]

- British commemorative stamps – Hodgkin was one of five 'Women of Achievement' selected for a set issued in August 1996. The others were Marea Hartman (sports administrator), Margot Fonteyn (ballerina/choreographer), Elisabeth Frink (sculptor) & Daphne du Maurier (writer). All except Hodgkin were Dames Commander of the Order of the British Empire (DBEs). In 2010, during the 350th anniversary of the founding of the Royal Society, Hodgkin was the only woman in a set of stamps celebrating ten of the Society's most illustrious members, taking her place alongside Isaac Newton, Edward Jenner, Joseph Lister, Benjamin Franklin, Charles Babbage, Robert Boyle, Ernest Rutherford, Nicholas Shackleton and Alfred Russel Wallace.[77]

- The Royal Society awards the Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship (named in her honour) "for outstanding scientists at an early stage of their research career who require a flexible working pattern due to personal circumstances, such as parenting or caring responsibilities or health-related reasons."[59]

- The Council offices in the London Borough of Hackney and buildings at University of York, Bristol University and Keele University are named after her, as is the science block at Sir John Leman High School, her former school.

- In 2012, Hodgkin was featured in the BBC Radio 4 series The New Elizabethans to mark the diamond Jubilee of Queen Elizabeth II. In this series a panel of seven academics, journalists and historians named her among the group of people in the UK "whose actions during the reign of Elizabeth II have had a significant impact on lives in these islands and given the age its character".[78]

- In 2015 Hodgkin's 1949 paper The X-ray Crystallographic Investigation of the Structure of Penicillin was honoured by a Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award from the Division of History of Chemistry of the American Chemical Society presented to the University of Oxford (England). This research is notable for its groundbreaking use of X-ray crystallography to determine the structure of complex natural products, in this instance, of penicillin.[79][80]

- Since 1999, the Oxford International Women's Festival has presented the annual Dorothy Hodgkin Memorial Lecture, usually in March, in honour of Hodgkin's work.[81] The Lecture is a collaboration between Oxford AWiSE (Association for Women in Science & Engineering), Somerville College and the Oxford University Museum of Natural History.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ First author as D. Crowfoot.

References[edit]

- ^ Anon (2014). "EMBO profile Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". people.embo.org. Heidelberg: European Molecular Biology Organization. Archived from the original on 11 August 2016. Retrieved 17 August 2016.

- ^ a b Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot (1937). X-ray crystallography and the chemistry of the sterols. lib.cam.ac.uk (PhD thesis). University of Cambridge. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.727110. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ Howard, Judith Ann Kathleen (1971). The study of some organic crystal structures by neutron diffraction. solo.bodleian.ox.ac.uk (DPhil thesis). University of Oxford. OCLC 500477155. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.459789. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 24 November 2017.

- ^ a b Howard, Judith Anne Kathleen (2003). "Timeline: Dorothy Hodgkin and her contributions to biochemistry". Nature Reviews Molecular Cell Biology. 4 (11): 891–96. doi:10.1038/nrm1243. PMID 14625538. S2CID 20958882.

- ^ Crace, John (26 September 2006). "Judith Howard, Crystal gazing: The first woman to head a five-star chemistry department tells John Crace what attracted her to science". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 17 August 2017.

- ^ a b "Chemistry Tree – Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". academictree.org. Archived from the original on 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ James, Michael Norman George (1966). X-ray crystallographic studies of some antibiotic peptides. bodleian.ox.ac.uk (DPhil thesis). University of Oxford. OCLC 944386483. EThOS uk.bl.ethos.710775. Archived from the original on 14 December 2019. Retrieved 27 March 2018.

- ^ John Blundell, Margaret Thatcher, A Portrait of The Iron Lady, 2008, pp. 25–27. Degree student, 1943–1947.

- ^ Blundell, T.; Cutfield, J.; Cutfield, S.; Dodson, E.; Dodson, G.; Hodgkin, D.; Mercola, D.; Vijayan, M. (1971). "Atomic positions in rhombohedral 2-zinc insulin crystals". Nature. 231 (5304): 506–11. Bibcode:1971Natur.231..506B. doi:10.1038/231506a0. PMID 4932997. S2CID 4158731.

- ^ a b c Dodson, Guy (2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011. ISSN 0080-4606. PMID 13678070. S2CID 61764553.

- ^ a b "Hodgkin, Prof. Dorothy Mary Crowfoot". Who's Who & Who Was Who. Vol. 2017 (online Oxford University Press ed.). Oxford: A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U173161 (subscription required)

- ^ a b Glusker, J. P. (1994). "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910–1994)". Protein Science. 3 (12): 2465–69. doi:10.1002/pro.5560031233. PMC 2142778. PMID 7757003.

- ^ a b Anon (2014). "The Biography of Dorothy Mary Hodgkin". news.biharprabha.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Hodgkin, Prof. Dorothy Mary Crowfoot". Who's Who & Who Was Who. Vol. 2017 (online Oxford University Press ed.). Oxford: A & C Black. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.) doi:10.1093/ww/9780199540884.013.U173161 (subscription required)

- ^ a b "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". Trowelblazers. 11 September 2014. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ "Calm Genius Of Laboratory And Home." Times [London, England] 30 Oct. 1964: 8. The Times Digital Archive. Web. 12 June 2017.

- ^ "Grace Crowfoot", Breaking Ground: Women in Old-World Archaeology, 1994–2004 Archived 23 August 2017 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ Dodson, Guy (2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011. ISSN 0080-4606. PMID 13678070. S2CID 61764553.

- ^ "Dorothy Hodgkin 1910–1994". "A Science Odyssey: People and Discoveries" a 1997 PBS documentary and accompanying book. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 26 August 2017.

- ^ Georgina Ferry, Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life, Granta Books: London, 1998, p. 20.

- ^ Thiel, Kristin (2016). Dorothy Hodgkin: Biochemist and Developer of Protein Crystallography. Cavendish Square Publishing, LLC. pp. 40–41. ISBN 9781502623133. Archived from the original on 24 March 2021. Retrieved 23 May 2019.

- ^ S.G. Rosenberg, "British Groundbreakers in the Archaeology of the Holy Land", Minerva, January/February 2008.

- ^ "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin | TrowelBlazers". 11 September 2014. Archived from the original on 7 October 2019. Retrieved 7 October 2019.

- ^ "The Nobel Prize in Chemistry 1964". NobelPrize.org. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ^ Oakes, Elizabeth H. (2002). International Encyclopedia Of Women Scientists. New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc. pp. 163. ISBN 978-0-8160-4381-1.

- ^ a b c Ferry, Georgina (1999). Dorothy Hodgkin : a life. London: Granta Books. ISBN 978-1862072855.

- ^ Lisa Tuttle, Heroines: Women inspired by Women, 1988.

- ^ "Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot". Encyclopedia.com. Charles Scribner's Sons. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot (1980). "John Desmond Bernal. 10 May 1901 – 15 September 1971". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 26: 16–84. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1980.0002. S2CID 72287250.

- ^ "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin, OM". Archived from the original on 12 January 2012. Retrieved 13 January 2012.

- ^ Dodson, Guy (2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011. ISSN 0080-4606. PMID 13678070. S2CID 61764553.

- ^ Young, Hugo (1989). One of us: a biography of Margaret Thatcher. London: Macmillan. ISBN 978-0-333-34439-2.

- ^ BBC UK Politics (19 August 2014). "Thatcher and Hodgkin: How chemistry overcame politics". BBC News. Archived from the original on 1 December 2017. Retrieved 20 July 2018 – via bbc.co.uk.

- ^ Yount, Lisa (1999). A Biographical Dictionary A to Z of Women In Science and Math. New York, NY: Facts On File, Inc. pp. 91. ISBN 978-0-8160-3797-1.

- ^ Anon (2014). "The Biography of Dorothy Mary Hodgkin". news.biharprabha.com. Archived from the original on 6 May 2017. Retrieved 11 May 2014.

- ^ "Award winners". University of Oxford. Archived from the original on 1 July 2014. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ Carlisle, C.H.; Crowfoot, D. (1945). "The Crystal Structure of Cholesteryl Iodide". Proceedings of the Royal Society A: Mathematical, Physical and Engineering Sciences. 184 (996): 64. Bibcode:1945RSPSA.184...64C. doi:10.1098/rspa.1943.0040. S2CID 38958402.

- ^ Crowfoot, D.; Bunn, Charles W.; Low, Barabara W.; Turner-Jones, Annette (1949). "X-ray crystallographic investigation of the structure of penicillin". In Clarke, H.T.; Johnson, J.R.; Robinson, R. (eds.). Chemistry of Penicillin. Princeton University Press. pp. 310–67. doi:10.1515/9781400874910-012. ISBN 9781400874910. Archived from the original on 6 May 2022. Retrieved 6 May 2022.

- ^ Hodgkin, Dorothy. "Beginning to work on vitamin B12". Web of Stories. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 14 October 2014.

- ^ a b "Hodgkin, Dorothy Mary Crowfoot". Encyclopedia.com. Cengage Learning. Archived from the original on 14 October 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2015.

- ^ Brink, C.; Hodgkin, D.C.; Lindsey, J.; Pickworth, J.; Robertson, J.H.; White, J.G. (1954). "Structure of Vitamin B12: X-ray Crystallographic Evidence on the Structure of Vitamin B12". Nature. 174 (4443): 1169–71. Bibcode:1954Natur.174.1169B. doi:10.1038/1741169a0. PMID 13223773. S2CID 4207158.

- ^ Rickes, E. L.; Brink, N.G.; Koniuszy, F.R.; Wood, T.R.; Folkers, K. (16 April 1948). "Crystalline Vitamin B12". Science. 107 (2781): 396–97. Bibcode:1948Sci...107..396R. doi:10.1126/science.107.2781.396. PMID 17783930.

- ^ Hodgkin, Dorothy Crowfoot; Pickworth, Jenny; Robertson, John H.; Trueblood, Kenneth N.; Prosen, Richard J.; White, John G. (1955). "Structure of Vitamin B12: The Crystal Structure of the Hexacarboxylic Acid derived from B12 and the Molecular Structure of the Vitamin". Nature. 176 (4477): 325–28. Bibcode:1955Natur.176..325H. doi:10.1038/176325a0. PMID 13253565. S2CID 4220926.

- ^ Hodgkin, Dorothy Crowfoot; Kamper, Jennifer; Mackay, Maureen; Pickworth, Jenny; Trueblood, Kenneth N; White, John G. (July 1956). "Structure of vitamin B12". Nature. 178 (4524): 64–66. Bibcode:1956Natur.178...64H. doi:10.1038/178064a0. PMID 13348621. S2CID 4210164.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b Weidman, Chelsea (12 May 2019). "Meet Dorothy Hodgkin, the biochemist who pieced together penicillin, insulin, and vitamin B12". Massive Science. Archived from the original on 10 August 2020. Retrieved 9 June 2020.

- ^ Brown, Andrew (2005). J.D. Bernal – the Sage of Science. Oxford University Press. pp. 137–40. ISBN 978-0-19-920565-3.

- ^ Ferry, Georgina (1998). Dorothy Hodgkin: A Life. London: Granta Books. pp. 94–101. ISBN 978-1-86207-167-4.

- ^ Grinstein, Louise S. (1993). Women in Chemistry and Physics: A Biobibliographic Sourcebook. Greenwood Press. p. 255. ISBN 9780253209078.

- ^ "Dorothy Hodgkin FRS – Scientists with disabilities | Royal Society". royalsociety.org. Retrieved 7 April 2023.

- ^ Walters, Grayson. "Not Standing Still's Disease". Archived from the original on 11 May 2021. Retrieved 3 December 2011.

- ^ "Mr Thomas Hodgkin". The Times. 26 March 1982.

- ^ Michael Wolfers, 'Hodgkin, Thomas Lionel (1910–1982)' Archived 24 September 2015 at the Wayback Machine, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, September 2004; online edn, January 2008, accessed 15 January 2010

- ^ "Dr Luke Hodgkin" Archived 23 September 2016 at the Wayback Machine, Academic Staff, King's College London.

- ^ "Fellows and governance of the Rift Valley Institute". riftvalley.net. Rift Valley Institute. Archived from the original on 19 April 2018. Retrieved 31 July 2016.

- ^ "Toby Hodgkin" Archived 24 June 2019 at the Wayback Machine, PAR Researcher Database.

- ^ a b "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin – Biographical". The Nobel Foundation. Archived from the original on 10 June 2017. Retrieved 10 March 2019.

- ^ "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". Science History Institute. June 2016. Archived from the original on 21 March 2018. Retrieved 20 March 2018.

- ^ a b Meyer, Michal (2018). "Sketch of a Scientist". Distillations. 4 (1): 10–11. Archived from the original on 14 April 2021. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ a b Anon (2017). "The Dorothy Hodgkin Fellowship". London: Royal Society. Archived from the original on 16 November 2016. Retrieved 2 November 2016.

- ^ "New biochemistry building renamed the Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin Building", University of Oxford, Department of Biochemistry website, May 2022.

- ^ Georgina Ferry, Dorothy Hodgkin – a life, Granta: London, 1998, pp. 335–42.

- ^ Ceausescu, Elena (1983). Stereospecific Polymerization of Isoprene. Pergamon. ISBN 978-0-08-029987-7.

- ^ Behr, Edward (1991). Kiss the Hand You Cannot Bite. Villard Books. ISBN 978-0-679-40128-5.

- ^ Rose, Hilary (1994). Love, Power, and Knowledge: Towards a Feminist Transformation of the Sciences. Indiana University Press. p. 139. ISBN 9780253209078.

- ^ "Search the Collection: Dorothy Hodgkin". National Portrait Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Dorothy Hodgkin". National Portrait Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 20 September 2017. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Dorothy Hodgkin". National Portrait Gallery, London. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "Digital Collections: Professor Dorothy Hodgkin". Science History Institute. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ "A Nobel laureate". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Cornforth, J. (1 August 1982). "Portrait of Dorothy Hodgkin, O.M., F.R.S.". Notes and Records of the Royal Society. 37 (1): 1–4. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1982.0001. PMID 11611057. S2CID 2632315.

- ^ "Portrait of Dorothy Hodgkin". The Royal Society. Archived from the original on 27 June 2018. Retrieved 27 June 2018.

- ^ Dodson, Guy (2002). "Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, O.M. 12 May 1910 – 29 July 1994". Biographical Memoirs of Fellows of the Royal Society. 48: 179–219. doi:10.1098/rsbm.2002.0011. ISSN 0080-4606. PMID 13678070. S2CID 61764553.

- ^ "Book of Members, 1780–2010: Chapter H" (PDF). American Academy of Arts and Sciences. Archived (PDF) from the original on 15 November 2011. Retrieved 25 July 2014.

- ^ Anon (2017). "Professional Awards". iotasigmapi.info. Iota Sigma Pi: National Honor Society for Women in Chemistry. Archived from the original on 23 March 2019. Retrieved 16 December 2014.

- ^ Minor Planet Center, "Hodgkin" Archived 4 March 2016 at the Wayback Machine.

- ^ "Reply to a parliamentary question" (PDF) (in German). p. 690. Archived (PDF) from the original on 1 May 2020. Retrieved 21 October 2012.

- ^ "Getting the Royal Society stamp of approval". New Scientist. Archived from the original on 5 July 2014. Retrieved 12 May 2014.

- ^ "The New Elizabethans – Dorothy Hodgkin". BBC. Archived from the original on 25 November 2012. Retrieved 30 May 2016.

- ^ "2015 Awardees". American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Archived from the original on 21 June 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "Citation for Chemical Breakthrough Award" (PDF). American Chemical Society, Division of the History of Chemistry. University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign School of Chemical Sciences. 2015. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 September 2016. Retrieved 1 July 2016.

- ^ "2019 Festival". Oxford International Women's Festival. 31 March 2018. Archived from the original on 9 October 2019. Retrieved 9 October 2019.

Further reading[edit]

- Papers of Dorothy Hodgkin at the Bodleian Library. Catalogues at Catalogue of the papers and correspondence of Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, 1828–1993 and Catalogue of the additional papers of Dorothy Mary Crowfoot Hodgkin, 1919–2003

- Opfell, Olga S. (1978). Lady Laureates : Women Who Have Won the Nobel Prize. Metuchen, NJ & London: Scarecrow Press. pp. 209–23. ISBN 978-0810811614.

- Dodson, Guy; Glusker, Jenny P.; Sayre, David (eds.) (1981). Structural Studies on Molecules of Biological Interest: A Volume in Honour of Professor Dorothy Hodgkin. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

- Hudson, Gill (1991). "Unfathering the Thinkable: Gender, Science and Pacificism in the 1930s". Science and Sensibility: Gender and Scientific Enquiry, 1780–1945, ed. Marina Benjamin, 264–86. Oxford: Blackwell.

- Royal Society of Edinburgh obituary (author: William Cochran)

- Ferry, Georgina (1998). Dorothy Hodgkin A Life. London: Granta Books.

- Dorothy Hodgkin tells her life story at Web of Stories (video)

- CWP – Dorothy Hodgkin in a study of contributions of women to physics

- Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin: A Founder of Protein Crystallography

- Glusker, Jenny P. in Out of the Shadows (2006) – Contributions of 20th Century Women to Physics.

- Encyclopædia Britannica, "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin" (author: Georgina Ferry, 2014)

- Wolfers, Michael (2007). Thomas Hodgkin – Wandering Scholar: A Biography. Monmouth: Merlin Press.

- Haber, Louis (1979). Women pioneers of science. New York: Harcourt. ISBN 9780152992026. OCLC 731559034.

- Glusker, J.P.; Adams, M.J. (1995). "Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin". Physics Today. 48 (5): 80. Bibcode:1995PhT....48e..80G. doi:10.1063/1.2808036.

- Johnson, L.N.; Phillips, D. (1994). "Professor Dorothy Hodgkin, OM, FRS". Nature Structural Biology. 1 (9): 573–76. doi:10.1038/nsb0994-573. PMID 7634095. S2CID 30490352.

- Perutz, Max (1994). "Obituary: Dorothy Hodgkin (1910–94)". Nature. 371 (6492): 20. Bibcode:1994Natur.371...20P. doi:10.1038/371020a0. PMID 7980814. S2CID 4316846.

- Perutz, M. (2009). "Professor Dorothy Hodgkin". Quarterly Reviews of Biophysics. 27 (4): 333–37. doi:10.1017/S0033583500003085. PMID 7784539.

External links[edit]

Media related to Dorothy Hodgkin at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Dorothy Hodgkin at Wikimedia Commons

- Dorothy Hodgkin on Nobelprize.org including the Nobel Lecture, 11 December 1964 The X-ray Analysis of Complicated Molecules

- Portraits of Dorothy Hodgkin at the National Portrait Gallery, London

- Works by or about Dorothy Hodgkin at Internet Archive

- Four interviews with Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin recorded between 1987 and 1989 in partnership with the Royal College of Physicians are held in the Medical Sciences Video Archive in the Special Collections at Oxford Brookes University:

- Professor Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin OM FRS in interview with Sir Gordon Wolstenholme: Interview 1 (1987).

- Professor Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin OM FRS in interview with Max Blythe: Interview 2 (1988).

- Professor Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin OM FRS in interview with Max Blythe: Interview 3 (1989).

- Professor Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin OM FRS at home talking with Max Blythe: Interview 4 (1989).

- Watch a lecture of Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin (1910–1994) at the 1988 Nobel Laureates Symposium at the annual meeting of the American Crystallographic Association, Philadelphia

- Dorothy Hodgkin featured on the BBC Radio 4 program In Our Time on 3 October 2019.

- "The exceptional life of Dorothy Crowfoot Hodgkin", BBC "Ideas" video, 27 September 2021

- 1910 births

- 1994 deaths

- 20th-century British biologists

- 20th-century British chemists

- 20th-century American women scientists

- Alumni of Somerville College, Oxford

- Alumni of Newnham College, Cambridge

- British biochemists

- British biophysicists

- British Nobel laureates

- British women biologists

- British women chemists

- Chancellors of the University of Bristol

- British crystallographers

- English biochemists

- English biophysicists

- English Nobel laureates

- Fellows of Somerville College, Oxford

- Fellows of the American Academy of Arts and Sciences

- Fellows of the Royal Institute of Chemistry

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of Wolfson College, Oxford

- Female Fellows of the Royal Society

- Foreign associates of the National Academy of Sciences

- Foreign Members of the Russian Academy of Sciences

- Foreign Members of the USSR Academy of Sciences

- Hodgkin family

- Recipients of the Lenin Peace Prize

- Members of the Order of Merit

- Members of the European Molecular Biology Organization

- Nobel laureates in Chemistry

- People from Beccles

- People from Warwickshire

- Presidents of the British Science Association

- Recipients of the Austrian Decoration for Science and Art

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Royal Medal winners

- Recipients of the Lomonosov Gold Medal

- X-ray crystallography

- Women Nobel laureates

- Recipients of the Dalton Medal

- Vitamin researchers

- 20th-century Quakers

- Presidents of the International Union of Crystallography

- British scientists with disabilities

- English people with disabilities