Great Gatsby Curve

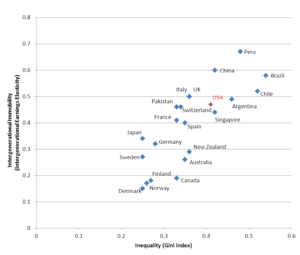

The "Great Gatsby Curve" is the term given to the positive empirical relationship between cross-sectional income inequality and persistence of income across generations.[1] The scatter plot shows the relationship between income inequality in a country and intergenerational income mobility (the potential for its citizens to achieve upward mobility).

The Great Gatsby Curve is based on research by Miles Corak, however the research was popularized by late professor and Chairman of the Council Economic Advisers Alan Krueger during his speech at the Center for American Progress in 2012[2][3][4] and the President's Economic Report to Congress.[5][6] Krueger, based on Miles Corak's work, dubbed the positive relationship between inequality and persistence, the "Great Gatsby curve", and he introduced it into popular and political discussion.

Explanation of the chart[edit]

The Great Gatsby Curve illustrates the strong positive correlation between the concentration of wealth in one generation and the capability of the following generation to move up the economic ladder compared to their parents (see Economic mobility). The horizontal axis shows the inequality, measured by a country’s Gini coefficient (a higher value means a more unequal distribution of income in society). The vertical axis shows persistence, measured by the intergenerational elasticity of income (IGE), where a lower intergenerational elasticity means there is higher income mobility in that country, i.e. children have a higher chance to earn more money than their parents.[7]

The Great Gatsby curve shows the relation between income inequality and intergeneration mobility (in this case between Gini Index and Intergenerational Elasticity respectively) and signifies that the relationship is positive and quite strong. So, it indicates that in countries with higher income inequality it is harder to overcome you parents' income level and vice versa.

The term "curve" to describe the relationship between the income inequality and elasticity can be misleading, because the trend line reflects a fairly straight line.

The countries with the most income equality and with highest intergenerational mobility are in the left bottom part of the graph; these are mostly Nordic countries with Canada, Australia, Japan, New Zealand and Germany not far from them. On the contrary, in the right top, countries with the greater level of inequality have less upward mobility, for example, the United Kingdom. The United States is in the middle.

The Great Gatsby Curve introduction[edit]

The name of the curve refers to the novel The Great Gatsby (1925) by Francis Scott Fitzgerald. The classic novel dramatises the gap between intergenerational wealth and the newly rich during the Jazz Age. The main character of this story, Jay Gatsby, was born in an impoverished family, but he earned lots of money and dramatically improved their social level during the years.

Judd Cramer, former staff economist at the Council of Economic Advisers, related the story of the birth of the Great Gatsby Curve to Miles Corak in responding to an email he sent him in September 2016:[8]

The short version of the story is: Reid Stevens and I were working with Alan for his speech at the Center for American Progress about the middle class. We got data from your paper and elsewhere and made the figure at Alan’s direction. Alan wanted a name for it; something that spoke about the rich staying rich, etc. We were in a meeting in the chairman’s conference room and he asked us to go brainstorm names. We went back to the room where many of the junior staffers sat together, we called it the bullpen, and after we explained the curve to all the staffers, we each put down one suggestion. Reid may remember the also-rans better than I do but I wrote down the Great Gatsby curve because of Gatsby’s trouble trying to jump social classes in spite of his money. A few of the other staffers teased me for my suggestion. None of the others were too great in my opinion; I remember a lot of the other names playing on white picket fences/silver spoons in their names.We then walked the list back over to Alan and his chief of staff, David Vandivier. Alan read all the names and chose the Great Gatsby curve. During that time in DC, Alan was in the business of promoting New Jersey wines and he gave Reid and me a bottle for our help with the speech that went well a few days later. I think that touches on the major points.

Krueger predicted that "the persistence in the advantages and disadvantages of income passed from parents to the children" will "rise by about a quarter for the next generation as a result of the rise in inequality that the U.S. has seen in the last 25 years."[9] The Great Gatsby Curve was used to advocate policies that aimed to reduce income and educational inequality by raising the minimum wage, providing subsidies for health insurance through the Affordable Care Act, etc.

Causes[edit]

The Great Gatsby Curve describes a relationship between the wealth of prior generations and the level of income of their children. According to the model, the correlation is strongly positive and can be transferred into reality.

There are many factors affecting the well – being of people and one of them is education. Education can be determined by parental income and their overall position in society.

Human capital can be measured by the level of education, experience, knowledge, skills, etc. Individual´s level of income highly depends on their human capital, which is collected and improved throughout the years starting from early age. The opportunities for the accumulation of human capital can be determined by the social status of one’s family. The quality of education is affected by the quality of schools. The schools are funded by a budget (provided by the state) which differs for every school district and the financial contribution is distributed between all the students in the community. The opportunities of individuals are improved by better connections, since they provide us with an easier entry into a certain market. Everyone’s identity is created by their social interactions, experience and direction of their development.

Richer neighborhoods tend to have better funded schools and public services, although the life in them is more expensive. Therefore, parental income plays a big role in the choice of a neighborhood and the community, since finances limit peoples’ options, causing the strong, positive correlation between income inequality and persistence of income across generations.[10]

Criticism[edit]

Journalist Timothy Noah argued:

you can't really experience ever-growing income inequality without experiencing a decline in Horatio Alger-style upward mobility because (to use a frequently-employed metaphor) it's harder to climb a ladder when the rungs are farther apart.[9]

Another journalist argued that a connection between income inequality and low mobility could be explained by the lack of access for un-affluent children to better (more expensive) schools and if this enabled access to high-paying jobs; or to differences in health care that may limit education and employment.[11]

However, some argue that the apparent connection may arise as an artifact of heterogeneous variance in ability across nations, questioning the need for intervention. It was shown that the manner in which the intergenerational income elasticity is defined, is by design associated with inequality.[12] Harvard economist Greg Mankiw noted that "this correlation is not particularly surprising", showing that comparisons of more diverse groups (like the US) with less diverse groups (like the population of Denmark) will automatically exhibit this phenomenon even when there are in fact no differences in the processes of mobility between these groups, i.e., the curve is an artifact of diversity.[13] His quote:[13]

Germans are richer on average than Greeks, and that difference in income tends to persist from generation to generation. When people look at the Great Gatsby curve, they omit this fact, because the nation is the unit of analysis. But it is not obvious that the political divisions that divide people are the right ones for economic analysis. We combine the persistently rich Connecticut with the persistently poor Mississippi, so why not combine Germany with Greece?

A blog[14] by M.S. at The Economist replied to Mankiw's counter-argument as follows:

The argument over the Great Gatsby curve is an argument about whether America's economy is fair. With his Germany/Greece and Mississippi/Connecticut analogy, Mr Mankiw has stumbled on a very convincing point: whether you are rich or poor in Europe or America depends to a great extent not on your own qualities or efforts, but on where you happen to be born. America is not a meritocracy, Mr Mankiw is saying; not only do those born rich tend to stay rich and vice versa, just being born in one state or another makes a huge difference to your lifelong earnings. Amazingly, he seems completely unaware that this is the case he's just made.

Economist Paul Krugman has also countered Mankiw's arguments in his column.[15]

The GGC suggests that a society can simultaneously pursue equality of opportunity (measured by mobility) and equality of outcomes (measured by cross-section differences). More specifically to the US, the curve challenges the recent viability of the "American Dream" by linking inequality to limits on opportunity, questioning whether the US has chosen to accept unequal outcomes in order to create equal opportunities. Thus, the Great Gatsby curve has been popular regarded as a challenge to Americans' beliefs.[16]

Theories of the Great Gatsby Curve[edit]

Source:[16]

As Durlauf et al. [1] says, it is important to bear in mind that these theories typically consider inequality in different meaning than the Gini index. They involve inequality in family structure, parents education and their occupational attainment, social influences etc.

Family investment models[edit]

In the classical model of intergenerational mobility, parents divide income between investments in child’s education and own consumption. Brighouse and Swift (2006, 2014) and Lazenby (2016) discuss these tradeoffs. The idea of this model is that parental investments do matter. Some factors for making decisions between these investments are, for example, psychic stress or credit constraints. Psychic stresses are associated with poverty and deprivation and can suppress the child’s ability to create human capital and for adults to convert the human capital into income. Credit-constrained families show higher intergenerational elasticities of income than unconstrained families because of the effect of additional income on investment in children. An important notice is that the degree to which adjustments in the cross-section income distribution are linked with changes in the distribution of credit constraints, ability, or altruism, can each lead to producing relations in the Great Gatsby Curve.

Skill models[edit]

A second model that can produce the Great Gatsby Curve is based on skill formation. From this point of view, the adult outcomes are influenced by the cognitive and non-cognitive skills acquired by dealing with a sequence of family inputs in order to produce both type of these skills during childhood and adolescence.

Nevertheless, there are two differences in comparison with the classical model. First, children are affected differently by family inputs throughout different periods of time, i.e., timing of family influences matters. Second, the inputs provided by families are more thorough than just purchasing educational investment. For example, inequalities in a way families are built (e.g., single parenthood versus family of two parents), matter. Furthermore, studies have supported the thesis that less affluent parents invest less in their children than more affluent ones. Also the impact of their investments dominates in case of less affluent parents at each investment level.

Social models[edit]

The concerns of the third type of the model are social interactions. The main idea is that segregation of the wealthy and poor into specific communities will have an impact on producing disparate social interactions between their children and so pass on the socioeconomic status across generations. The Great Gatsby Curve can develop when changes in the cross-section distribution of income modify the nature of the equilibrium segregation of families.

Social models of intergeneration mobility highlight two distinct forces linking mobility to the level of economic segregation. Firstly, they highlight the relationship between income distribution in school districts and educational expenditures, with the understanding that this is dependent on local provision of public education. Secondly, these models consider the impact of neighbourhoods on educational outcomes, including the role of social interactions such as peer effects, social learning, norms, and social networks, as well as other factors like environmental quality (however in total school quality probably does not overweight the impacts of neighbourhood quality). Finally it is important to note that both of these forces are connected; mainly because family income affects future child income by having an effect on the choice of neighbourhood.

Political economy[edit]

Another theory of the cause of the Great Gatsby Curve puts stress on consequences of redistributive policies emerging from the choices of voters. These models put a strong emphasis the role of the political process in determining public educational investments. The redistribution preferences of voters are potentially formed by their beliefs, and when these beliefs are influenced by inequality, another channel for generating a Great Gatsby Curve is being formed (higher inequality generates demand for higher redistribution - because the median voter becomes relatively poorer).

Furthermore studies suppose that beliefs about fairness can lead to different voters preferences (that can lead to multiple equilibria in mobility and equality). And that can be another explanation of the cross country GGC. As an examples we can mention the “American Dream” and “Euro-pessimism.” In an “American Dream” equilibrium, the society believes that income is determined by effort and social mobility is high. Therefore, taxes and redistribution are low, individuals invest more and make higher effort, and inequality is higher. On the other hand, in a “Euro-pessimism” equilibrium, the society believes that luck, birth, connections, and corruption are the major determinants of income. Taxes, and redistribution is higher; individuals put less effort and invest less, and inequality is lower. So in general; in Europe the inequality is lower and mobility higher compared to the US.

The curve is also connected with meritocracy. A study showed that the more meritocratic societies, the greater inequality and lower mobility due to the incentives to invest in descendants are enhanced among the wealthy.

Aspirations[edit]

Another perspective for explaining the Great Gatsby Curve is the role of aspirations in determining individual choices. While skills provide the ability to act, aspirations contribute to the ability to identify and set goals with the intention to try to achieve these goals. Aspirations are affected by family and social influences in such ways that generate significant dispersion in ambitions with the increase in inequality. This can lead to a GGC in the same way that the family and social models produce the relationship.

The idea is that the experiences, places and individuals who are inside someone’s aspiration window influence the way their ‘aspiration gap’ is going to be constructed. The ‘aspiration gap’ could be defined as the distance between the status achieved and the status we aspire to achieve. When the “aspiration gap” is too small, there is no motivation to put in more effort which results in small investments. Furthermore, when the “aspiration gap” is too large, even with high effort, the desired outcome will not be achieved, leading also to low investments as the result of frustrated aspirations. Both a large and a small gap can potentially result in a society with high inequality.

The position of the countries[edit]

The best score according to the Great Gatsby Curve was achieved by the Nordic countries.[9] Denmark, Norway, and Finland all fell at the bottom-left part of the curve. As another Nordic country, Sweden is situated also near to the rest of the Nordic countries, despite a bit of a bit higher intergenerational income mobility.[17] This means that a child in a low-income family has a better opportunity to move up the economic ladder than a child in a similar situation in a country with higher inequality and higher elasticity. It can be caused by the fact that people in these countries have to pay higher taxes, and the education systems in this are countries are often free of charge. Other countries near the left-bottom corner are Japan and Germany. The majority of European countries have a Gini coefficient between 0.3 and 0.4. These countries, such as Switzerland, Italy, France, and United Kingdom, are situated in the middle of the Great Gatsby Curve.[18] Surprisingly, the United States of America, which is perceived as the country of equal opportunities, is located in the middle of the curve. But in the US, and unequal income distribution and a higher dependency on a parent's income means there is less opportunity for children in different economic classes to move upward than elsewhere.[19] The United States of America achieved an elasticity score of 0.47 from the research of Miles Corak.[20] This score means that slightly under half of what a child is expected to earn depends on their parent's income. In the US, nowadays, there is an increase in the chances of rich children growing up wealthy, and poor children remain poor in adulthood. Countries that are at the top-right of the curve include several developing countries. Countries in Latin America have a Gini coefficient above 0.5 and Corak's scores between 0.5 and 0.6.[21]

Interesting research was done focusing on Latin America. The levels of economic inequality in Latin American are enduring and abnormally high in comparison with other parts of the world (Lopez-Calva and Lustig, 2010). A significant feature of this level of inequality is allocation of income and wealth concentrated at the top of the distribution. This results in an extensive disparity between the middle class and the rich. In association with the GGC and the high inequality, low levels of economic mobility have been taken note of in Latin America.

For Brazil, an intergenerational elasticity of 0.66 for earnings was found by Ferrerira and Veloso (2006), while Dunn (2007) found an intergenerational elasticity of between 0.69 and 0.85 which depends on the age range of the male offspring. Furthermore, for Chile, intergenerational elasticities between 0.57 and 0.73 for men were declared by Nunez and Miranda (2010). For Mexico, with the estimation to permanent incomes for both generations, the intergenerational elasticity for earnings was estimated to be about 0.67. These numbers compare very unfavourably with, for example, the United States. When using transition tables findings, an economic mobility in these countries is characterized by high persistence at the top of the income distribution, but more mobility for middle and lower classes, which was noted by Torche (2014).[16]

Another research considered inequality and intergenerational mobility in educational attainment (instead of income and earnings) using data for 18 Latin American Countries throughout the last 50 years. A positive association between income inequality and intergenerational persistence in educational outcomes was found. The studies point out that educational mobility differs heavily across countries.

Several papers have shown that the Great Gatsby Curve is also apparent when comparing different regions within a given country. Such a subnational Great Gatsby Curve was found for the United States,[22] Italy,[23] and China.[24] A 2023 study further found that the subnational Great Gatsby Curve can already be found when comparing counties in the United States at the beginning of the 20th century.[25]

Another explanation of the Great Gatsby Curve[edit]

Income inequality and Income mobility[edit]

We can see the Great Gatsby curve from another perspective, such as how many generations it takes for a low-income family to reach the average income.[26] The relationship between inequality and mobility can also be seen using the number of generations, as the time, which is necessary to the improvement of low-income family to the social leader.[27] As we can expect in countries with better upward mobility, the process will last fewer generations for low-income families to reach the country's average income. The OECD created a bar chart that compares the number of generations necessary for low-income families to get the average income in countries part of the OECD.[28] As in the classical interpretation of the Great Gatsby Curve, the lowest inequality can be seen in Nordic countries, and it only takes about two to three generations. According to the OECD report, the People's Republic of China is situated on the other side of the curve. Due to the higher inequality and high elasticity, it takes seven generations for a low-income family to reach the average income.

Income inequality and Educational mobility[edit]

The Great Gatsby Curve can also be modified for educational mobility. Upward academic mobility is expected to be higher in countries with low-income inequality.[29] Suppose we measure the differences between the educational level of parents and the educational level of children. In that case, we find out that countries with less income inequality tend to have higher upward academic mobility, and children have better chances to gain a higher educational level than their parents.[30] Using OECD upward educational mobility data from its 2018 education report, we measured academic mobility upward, on the vertical axis, against income inequality, on the horizontal axis. Unlike the previous charts, higher values along the vertical axis mean more upward mobility. Thus, the line has a negative slope, in contrast to the standard Great Gatsby Curve or Great Gatsby Curve for income inequality and income mobility. As it is shown in the chart below, children from countries with low-income inequality have better chances to earn higher education than their parents. This type of Great Gatsby Curve is used by OECD when they design their educational policies.

References[edit]

- ^ a b Durlauf, Steven N.; Kourtellos, Andros; Tan, Chih Ming (2022). "The Great Gatsby Curve". Annual Review of Economics. 14 (1): 571–605. doi:10.1146/annurev-economics-082321-122703. ISSN 1941-1383.

- ^ Krueger, Alan (12 January 2012). "The Rise and Consequences of Inequality in the United States" (PDF).

- ^ Krugman, Paul (15 January 2012). "The Great Gatsby Curve". New York Times.

- ^ "The Great Gatsby Curve - Explained". Bloomberg Visual Data. 6 October 2013.

- ^ "Economic report of the President" (PDF). United States Government Printing Office. February 2012.

- ^ Sakri, Diding; Sumner, Andy; Yusuf, Arief Anshory (2023). "Great Gatsby and the Global South: Intergenerational Mobility, Income Inequality, and Development". Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009382700. ISBN 9781009382700. S2CID 257714041.

- ^ Corak, Miles. “Income Inequality, Equality of Opportunity, and Intergenerational Mobility.” The Journal of Economic Perspectives 27, no. 3 (2013): 79–102. JSTOR 41955546.

- ^ Corak, Miles (2016-12-04). "How The Great Gatsby Curve got its name".

- ^ a b c Noah, Timothy (13 January 2012). "White House: Here's Why You Have To Care About Inequality".

- ^ Durlauf, Steven N.; Seshadri, Ananth (2018-04-01). "Understanding the Great Gatsby Curve". NBER Macroeconomics Annual. 32: 333–393. doi:10.1086/696058. ISSN 0889-3365. S2CID 1193458.

- ^ DeParle, Jason (4 January 2012). "Harder for Americans to Rise From Lower Rungs". The New York Times.

- ^ Berman, Yonatan (7 Sep 2017). "Understanding the Mechanical Relationship between Inequality and Intergenerational Mobility". doi:10.2139/ssrn.2796563. SSRN 2796563.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ a b Mankiw, Greg (18 July 2013). "Observations on the Great Gatsby Curve".

- ^ S., M. (22 July 2013). "The Great Gatsby curve - Don't worry, old sport". The Economist.

- ^ Krugman, Paul (22 June 2013). "Greg Mankiw and the Gatsby Curve".

- ^ a b c Durlauf, Kourtellos, Ming Tan (February 2022). "The Great Gatsby Curve" (PDF).

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ "Here is the source for the “Great Gatsby Curve” in the Alan Krueger speech at the Center for American Progress on January 12", Corak, Miles (12 January 2012)

- ^ "Here is the source for the “Great Gatsby Curve” in the Alan Krueger speech at the Center for American Progress on January 12", Corak, Miles (12 January 2012)

- ^ "Here’s Where the US Falls on the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’", Hoff, Madison (23 February 2020)

- ^ [1], Corak, Miles (12 January 2012) "Here is the source for the “Great Gatsby Curve” in the Alan Krueger speech at the Center for American Progress on January 12"

- ^ "Here is the source for the “Great Gatsby Curve” in the Alan Krueger speech at the Center for American Progress on January 12", Corak, Miles (12 January 2012)

- ^ Raj Chetty, Nathaniel Hendren, Patrick Kline, Emmanuel Saez, Where is the land of Opportunity? The Geography of Intergenerational Mobility in the United States , The Quarterly Journal of Economics, Volume 129, Issue 4, November 2014, Pages 1553–1623, https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qju022

- ^ Güell, M., Pellizzari, M., Pica, G. and Rodríguez Mora, J.V. (2018), Correlating Social Mobility and Economic Outcomes. Econ J, 128: F353-F403. https://doi.org/10.1111/ecoj.12599

- ^ Fan, Yi, Junjian Yi, and Junsen Zhang. 2021. "Rising Intergenerational Income Persistence in China." American Economic Journal: Economic Policy, 13 (1): 202-30.

- ^ Battiston, D, S Maurer, M Potlogea and J Rodríguez Mora (2023), ‘DP18249 The Dynamics of the “Great Gatsby Curve”, and a look at the curve during the Great Gatsby Era‘, CEPR Discussion Paper No. 18249. CEPR Press, Paris & London. https://cepr.org/publications/dp18249

- ^ "Here’s Where the US Falls on the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’", Hoff, Madison (23 February 2020)

- ^ "Here’s Where the US Falls on the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’", Hoff, Madison (23 February 2020)

- ^ "A Broken Social Elevator? How to Promote Social Mobility", OECD (15 June 2018)

- ^ "Trends in educational mobility: How does China compare to Europe and the United States?", Rob J, Gruijters; Tak Wing Chan; John, Ermisch (19 March 2019)

- ^ "Here’s Where the US Falls on the ‘Great Gatsby Curve’", Hoff, Madison (23 February 2020)

Further reading[edit]

- Stewart, Matthew (June 2018). "The 9.9 Percent Is the New American Aristocracy". The Atlantic.