Hamilton Easter Field

Hamilton Easter Field | |

|---|---|

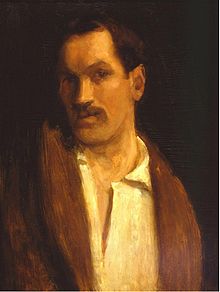

Hamilton Easter Field, Self Portrait, about 1898, oil on panel, 12 in. x 18 in. | |

| Born | April 21, 1873 Irvington, New Jersey, US |

| Died | April 9, 1922 (aged 48) New York City, US |

Hamilton Easter Field (1873–1922) was an American artist, art patron, connoisseur, and teacher, as well as critic, publisher, and dealer. Highly regarded for his knowledge of Japanese prints and his passion for American folk art and crafts, he was also praised for his devotion to contemporary American art, for his defense of non-juried art exhibitions, and for the support he gave to talented artists. At his death, the painter Wood Gaylor said of him: "Mr. Field was one of those rare personalities that come to the front once in a century or so. A combination of painter, critic, teacher and editor, he gave all his time and genius to the furtherance of American art...."[1]

Early life and training[edit]

Field was educated at Brooklyn Friends School whose advanced curriculum included classes in drawing.[2]: 29 Initially aiming at a career in architecture he attended the Polytechnic Institute of Brooklyn from 1888 to 1892 and in 1893 enrolled in the Columbia School of Mines, Engineering and Chemistry.[3] He left Columbia in 1894 to study at Harvard University but left after only a few months in order to travel to Paris where, influenced by wealthy and cultured members of his mother's family, he decided to devote his life to art.[4]: 29 In Paris he studied under Gustave Courtois and Raphaël Collin at Académie Colarossi.[2]: 30 [5] He also received informal instruction from Jean-Léon Gérôme and subsequently studied privately under Lucien Simon and Henri Fantin-Latour. These artists were all traditional academicians and, under their guidance, he adopted a style that had little in common with the avant-garde artists with whom he later associated.[3][6][note 1] In 1898 Field went to Concarneau in Brittany where Théophile Deyrolle and Alfred Guillou had founded an art colony. There he met eight-year-old Robert Laurent and his parents.[2]: 32 Field recognized and nurtured Laurent's talent as an artist, eventually bringing him (at age twelve) to live in his home in Brooklyn and thereafter remaining his close associate for the rest of his life.[7]: 85

The family that eased Field's immersion in the art world of Europe attained its wealth and influence in Parisian art circles by the manufacture of porcelain in Limoges, France. Their factory, Haviland & Co., was run by a brother of Field's mother, David Haviland. His son, Field's cousin Charles, was married to the daughter of a prominent art critic, Philippe Burty, who was both a champion of impressionism and an early admirer of Asian, particularly Japanese, art.[2]: 30 Possessing a winning personality and outgoing nature, Field was able to use the connections he made through his art teachers and his Haviland relatives together with his skill identifying and purchasing works of art and antiques to attain a reputation as successful Parisian artist and connoisseur.[8]

Career[edit]

Artist, connoisseur, collector[edit]

Field's success as an artist was limited by the number and intensity of his other interests.[6] People he met in Paris, particularly his teacher Collin and the critic Burty, introduced him to Asian art and he soon became first a collector of and then an authority on Japanese prints. So great was his knowledge that at his death he was considered the "greatest authority in America on Japanese prints."[3][8]

Field remained at his base in Paris for most of fifteen years, traveling from there to other locations in France, throughout Europe, and into Asia in order to study art and collect both art and antiques. In describing Field's "immense studio" in 1901, a reporter for the Brooklyn Daily Eagle exclaimed over the tapestries, paintings, and prints that covered the walls along with cases holding engravings, Japanese prints, and rare books crowding the floor called it an "artistic paradise in Paris."[9]

When he returned to Brooklyn in 1902 for a three-year stay, Field brought with him young Robert Laurent and his parents. The four of them lived with Field's mother in the Columbia Heights house that she owned and in which Field had been raised.[7]: 84

Over a period of three years, beginning in 1905, Field and his mother made frequent trips to Europe, visiting Paris, London, Rome, Dublin, Florence, Zürich, and Budapest.[7]: 86 Laurent's parents returned to France at this time. Laurent returned home with them to complete his schooling then, in 1907, joined Field and his mother on their return to Brooklyn.[3]

In 1907 while at home between trips, Field sold some of his 1,000 Japanese prints.[10] Returning to Europe in 1908, Field opened a studio apartment in Rome and made it his primary residence through May 1909.[3][11]

In 1909 Field's second cousin Frank Burty Haviland introduced Field to his friend Pablo Picasso. Field then commissioned Picasso to make a group of eleven decorative paintings to occupy the walls of his library in Brooklyn.[12] By 1915 Picasso had completed at least eight of the panels, though he later abandoned the project, and Field never saw the results of Picasso's labor.[13] One of the completed paintings, "Pipe Rack and Still Life on a Table," now in the collection of The Metropolitan Museum of Art,[14] was intended to be placed over a door to the room. It contains Field's initials, HEF, at the lower right.[13] Picasso's unfinished commission would have represented the first Cubist decorative interior in the United States.

In 1910 Field returned from the last of the overseas trips that he took with his mother and thereafter the two of them spent most of the warm months in Maine and the rest of the year in Brooklyn. After her death in 1917 Field continued this pattern of dual residence.[2]: 33 [15] Field's favored locale in Maine was a coastal community called Ogunquit that had begun attracting artists at the end of the nineteenth century. Field had and his mother had begun summering there in 1904 and later bought a house they called Thurnscoe where Field made paintings that he showed in a commercial gallery in New York in 1905.[5][16][17][note 2]

Taking advantage of his solid reputation as an authority on Japanese prints and European art in general and capitalizing on the quality and extent of his personal collections Field was able to establish himself as a successful art dealer afterwards.[8]

Art patron, educator, gallery owner, principal in artists' associations[edit]

In 1905 Field was given a solo exhibition at the William Glausen Gallery in Fifth Avenue in New York.[5] All the paintings he showed were in a traditional style, revealing little or no influence of Cubism or other progressive movements.[7]: 86 They varied widely in locales depicted, if not in the style in which they were made. An article in the New York Times describes the fifty works on show as "landscapes, townscapes, marines, figure pieces, and sketches from the coast of Maine and Long Island Sound, from Paris and New York, from France and Italy--even from Finland and Japan"[18]

In 1912 Field purchased the building next door to his mother's home and remodeled it from a boarding house into an art gallery on the first two floors with rooms rented out to boarders on the other floors. The gallery, called Ardsley House, held frequent, brief exhibitions that rarely gained mention in the New York press.[2]: 33 [19][20][note 3] Ardsley House exhibitions were frequent and short. Most consisted of paintings by Field himself and by Robert Laurent or of prints from the collections of Field and Laurent. Field sought to attract "persons of refinement and culture" as boarders, particularly artists and musicians.[2]: 33

Field's first reported work as art teacher took place in 1905 before he and his mother departed on their extended European travels. At that time Field gave art instruction to boys at the Little Italy Neighborhood Settlement House.[24][note 4] In 1911 Field began to build studios at Perkins Cove in Ogunquit designing them in the form of local fishermen's shacks and using parts from old barns in their construction and by 1914 had begun operating a summer school there.[7]: 89–90 [28][note 5]

In 1916 Field bought a building at 110 Columbia Heights which, like Ardsley House, was both adjacent to his mother's home and in use as a boarding house. One of its former tenants was John Roebling who had chosen the location because it gave him views of the Brooklyn Bridge while it was being constructed. Field turned it into studios for use as an art school while keeping other rooms to be let out to boarders and made available to needy artists either for free or at low rent. He called the building the Ardsley Studios and the school the Ardsley School of Modern Art.[7]: 98 The school attracted progressive young painters who had attended classes at the Art Students League in New York, including students of Kenneth Hayes Miller. They included Yasuo Kuniyoshi, Niles Spencer, Stefan Hirsch, Adelaide Lawson, and Lloyd Goodrich.[7]: 89 Artists who occupied rooms in the boarding house part of the building included Hirsch, Kuniyoshi, Katherine Schmidt, and Elsa Rogo.[2]: 36 [note 6]

Field did not attempt to impart a favored style on his students but rather emphasized individual development based on an instinctive approach to art. Overall, he hoped to engender a version of modernism that was uniquely American.[7]: 93–94 He also indulged in a lively social life organizing get-togethers among artists that included drunken costume parties.[2]: 26

As Field's aesthetic taste evolved he became more and more attracted to early Americana, including rustic furniture and rugs as well as pictorial art in a naïve style. In about 1917 he bought a farm near Ogunquit, in Neddick, Maine. He called it Sowerby Farm and began referring to himself as a farmer.[4]: 134–136 [29][30]

From 1916 onward Field became increasing involved in the work of artists' associations. In that year he was elected president of the Brooklyn Artists Association.[2]: 35 A year later he joined the Society of Independent Artists, became its corresponding secretary, and began to participate in the group's exhibitions. From 1918 to 1920 he served on the society's board of directors, leaving over a disagreement with Walter Pach concerning a policy of giving publicity to some artist-members and not others. In 1920 he formed a new organization, Salons of America, which would, like the society, exhibit the work of its member artists, but which would be free of the taint of favoritism.[7]: 102

Critic, editor, publisher[edit]

In 1913 Field wrote and self-published a book, The technique of oil paintings : and other essays.[7]: 91 Subsequently, he established himself as a well-known and highly respected art critic.[31] In 1919 he succeeded his friend Helen Appleton Read as art editor of the Brooklyn Daily Eagle.[7]: 98, 100 In that year and the next he wrote reviews on exhibitions and artists for Arts and Decoration.[32][note 7] In 1919 he also founded The Arts magazine and became its editor, publisher, and main contributor. The money he gained from subscriptions and advertising permitted him to expand it and increase the frequency from quarterly to monthly. It contained sixty-four pages at the time of his death in 1922.[2]: 28 [6]

In addition to his skill as critic, editor, and publisher, Field showed a flair for self-publicity. Beginning in 1901 when a reporter described in great and enthusiastic detail his spacious studio overlooking the Seine to the day of his death twenty one years later he was frequently able to attract the attention of reporters from the Brooklyn press. There were short notices both on the art exhibitions he staged and on the musical and other social gatherings that he and his mother held in her Brooklyn home. Their travels together and their departures to and returns from their summer sojourns were also routinely reported.[note 8] There were also lengthy reviews of Field's possessions and their display in his home. In 1902 the contents of his "beautiful" Brooklyn studio received notice, with its seventeenth century fireplace, Renaissance tapestries, Gothic chests, a painting by Fragonard and one attributed to Velázquez, and other antiquities.[35] In 1904 a reporter described these possessions in detail saying Field's studio was "nothing short of a revelation" and that its contents were all "worth the study of the antiquary."[36] An article published in 1905 focused on the superb view from the third floor windows of Field's studio as well as the "wonderful old French furniture" and two carved oak columns overlaid in gold.[37] A few years later a reporter contrasted the "almost medieval" studio interior with the "view by night of the New York skyscrapers and lights of Manhattan."[38] In 1913 a reporter listed some of the art Field displayed in his studio including works by Winslow Homer, Max Weber, John La Farge, Gaston La Touche, and Armand Guillaumin. He also described the elaborate decorations that Field and Laurent created for a room adjoining the studio.[39] In 1917 a reporter described the lower basement of Field's home "with its rare prints and curios, and the weird and Oriental lighting effects [that] transport one out of matter of fact Brooklyn and into the lazy luxury and the peculiar mysticism of Turkish tradition."[40]

Legacy[edit]

The Arts magazine continued to be published from Field's death until the early 1930s with Forbes Watson as editor.[41][42] The artists' exhibition association, Salons of America, continued under the leadership of Gaylor, Laurent, and Kuniyoshi until the middle 1930s.[7]: 103

Field's will left his entire estate to Robert Laurent who used some of the funds he inherited to establish Hamilton Easter Field Art Foundation in 1929.[4]: 137 The foundation was a collaborative effort involving men who had benefited from Field's support. In addition to Laurent the founders included Wood Gaylor, Stefan Hirsch, and David Morrison.[43] The foundation aided progressive artists by using funds obtained in annual auctions of works by established artists to purchase the works of young and struggling ones.[6]

The buildings at 104, 106, and 110 Columbia Heights continued to attract members of the arts community as residents. Robert Laurent remained, as owner of the properties. Yasuo Kuniyoshi and his wife the artist Katherine Schmidt continued to live there and, during the 1920s and 1930s others, including the writers John Dos Passos and Hart Crane would as well.[7]: 103 The summer school at Ogunquit continued under Laurent's leadership until 1960.[7]: 103

At the time of Field's death the Brooklyn Daily Eagle invited seven prominent men of the New York art world to pay tribute to his memory. The artist, Stephan Bourgeois, wrote that Field was an exemplary teacher, bringing out the distinctive personal style that his students possessed; that he opened his house to struggling artists; and that he was a "farseeing and indulgent critic" whose strong personality helped The Eagle become one of the leading art papers of the country. The museum director, William Fox, praised Field's skill as collector and connoisseur, saying that his extensive collections of art from many lands and epochs showed his singular sensitivity "to beauty in all its art manifestations" and noting that he revered the art of the past while also being receptive to the new. The artist Gaston Lachaise mentioned Field's enthusiasm, charming optimism, and keen sense of fair play "which have made him stand head and shoulders over the opportunists frequently to be met with in the art world." Wood Gaylor said, "Mr. Field was one of those rare personalities that come to the front once in a century or so. A combination of painter, critic, teacher and editor, he gave all his time and genius to the furtherance of American art, and it was to this drain on his vitality that we are deprived of many more years of active support." Max Weber praised Field's sincerity, intelligence, sympathy, and sociability. Joseph Stella called Field a rare expert of "everything great in art, past and present." Maurice Sterne called attention to Field's "rare nature: dreamer and man of action, lover of beauty irrespective of time and place. He could appreciate a Chinese masterpiece, a Greek original, or the work of an unknown contemporary: one who not only loved the latter but generously helped struggling earnest workers."[1]

Fields was interred in the Friends Quaker Cemetery in Brooklyn's Prospect Park.[44] A reporter for the society weekly, Brooklyn Life, offered the following assessment of Field in a lengthy profile published in 1912 that showed how much stature he had already achieved a full ten years before the eulogies that accompanied his death: "Possessed of magnetic personality, a broad-minded culture and with intense enthusiasm, his ready sympathy and quick recognition of other men's powers and ability made him much sought after and extremely popular in Paris during the year years immediately preceding and following the exposition. ... Better known as a promoter, collector and connoisseur in art, Mr. Field exemplifies in his work the higher ideal individuality demanded in the past for the rank of an artist; a certain largeness of vision, a command and knowledge of the sister arts of music, drama and literature."[45]

In the catalog for a 1934 exhibition of works purchased by the Hamilton Easter Field Foundation Elsa Rogo listed the artists who Field had encouraged or who had benefited from his financial support. Most of them had taken classes at the Art Students League and quite a few were members first of the Society of Independent Artists and then Salons of America. The list included George Biddle, Alexander Brook, Louis Bouché, Emile Branchard, John Cunning, Vincent Canadé, James Carroll Beckwith, Andrew Dasburg, Charles Demuth, Edwin Dickinson, Alfeo Faggi, Arnold Friedman, Wood Gaylor, Samuel Halpert, Pop Hart, Marsden Hartley, C. Bertram Hartman, Stefan Hirsch, Bernard Karfiol, Leon Kroll, Adelaide Lawson, Gaston Lachaise, Robert Laurent, John Marin, Henry Lee McFee, Kenneth Hayes Miller, David Herron Morrison, Georgia O'Keeffe, Jules Pascin, Charles Sheeler, Katherine Schmidt, Florine Stettheimer, Joseph Stella, Maurice Sterne, Eugene Speicher, Max Weber, Abraham Walkowitz, Russel Wright, Arnold Wiltz, and William H. K. Yarrow.[6][note 9]

Family and personal life[edit]

Field was born in Brooklyn on April 21, 1873, to Aaron Field and his wife, Lydia Seaman Haviland Field. Aaron Field was a prosperous merchant who came from a family of prosperous merchants. He was born in New York in 1829 and died in Brooklyn in 1897.[46]: 1322 [47] Lydia Field was a leading member of Brooklyn society, a founding member of Swarthmore College, and an ardent supporter of the woman's suffrage movement. She was born in 1838 in Jerhico, Long Island, and died in Brooklyn in 1917. Both parents belonged to prominent Quaker families whose ancestors had emigrated to America in the seventeenth century.[8][46]: 1322

Field had an older brother, Herbert Haviland Field, and a younger sister, Anna Haviland Field.[46]: 1323 He also had an older step-sister, Fannie Field, and two older step-brothers, Henry Cromwell Field and Edward Stabler Field.[46]: 1323 The step-brothers' mother, Charlotte (Cromwell) Field, was born in 1831 and died in 1863.[46]: 1322 [48][49] Anna died in 1883 when Field was ten years old.[50] Henry died in 1885 when Field was 12 years old and Herbert died in 1921, twelve months before Field.[46]: 1323 [51][52]

Field, his parents, and his siblings were well connected members of Brooklyn society. Their names appeared in editions of the Brooklyn Blue Book and Long Island Society Register and their accomplishments, travels, weddings, and other social occasions were regularly chronicled in Brooklyn Life, a glossy weekly similar to the better known Town & Country magazine.[note 10] Herbert was a highly educated scientist who developed and marketed a system, called the Concilium Bibliographicum, for collecting, organizing, and disseminating information about research in the sciences.[4]: 132 Edward was a merchant like his father, importing dry goods into New York from Europe.[4]: 131

Field's financial resources were extensive. He earned money as an art dealer, profitably selling Japanese prints and other works that he had bought during his travels. While some of his students and boarders paid him little or nothing, others gave him fees and rent of some unknown amount. He earned money from his writings, again of unknown amount. During his mother's life he lived in her home in Brooklyn and she accompanied him on most of his travels, presumably paying all or most of his expenses. Although he and his brothers received small legacies in his father's will, she was her husband's main beneficiary.[2]: 28 [21] In 1905 she sold the family estate in Great Neck thereby increasing her revenues extensively.[56][note 11] As a biographer of Field's brother Herbert points out, first his two parents then his widowed mother supported Field's education, his study in Paris, his travels through Europe, his acquisition of fine art, books, and antiquities, and his purchase of properties in Brooklyn and Maine.[4]: 99–101

Although Field was a respected benefactor of struggling progressive artists, he was less generous in helping both his step-brother Edward and his brother Herbert when they were in need. When Edward's import business failed during World War I, he and his wife Lydia (called Lilla), came to live in Field's art school-cum-boarding house at 110 Columbia Heights. Lilla ended up with responsibility for managing the house, caring for the seventeen boarders, and stoking its coal furnace.[4]: 132 During the same period Herbert's project to build an information service for scientists had lost momentum and was close to failing. His hopes of rescue by his family were disappointed when it became apparent that his mother had left her entire estate to Field and when Herbert's subsequent efforts to gain Field's support for the project came to nothing. Embittered by the experience, Herbert wrote his wife to complain that Field was irresponsible and self-centered. He said that Field was spending extravagantly to indulge his enthusiasms for art, for support of struggling artists, for development of his properties in Brooklyn and Maine, and for maintenance of his "companions," the boys and young men with whom he shared his life.[4]: 136–137, 192

Only one source mentions Field's sexual orientation. In a telephone interview in 1986 Field's friend Lloyd Goodrich said, "What you fundamentally have to understand about Hamilton Easter Field was that he was a homosexual. The townsfolk of Ogunquit didn't understand him, and his behavior occasionally scandalized them."[2]: 26 Neither Goodrich nor any other source has linked Field's reported homosexuality with his apparent need to gather around him boys and young men with whom to share his life. In fact, apart from Robert Laurent only one of the young men whom Field brought to live with him is known by name.[note 12] That is Raymond Webber, born and raised on a farm in York County, Maine, who, as a sixteen-year-old was recorded as living with Field as his "companion" in 1920.[60] In addition, Herbert Field wrote that his brother brought a young African-American boy into his house in 1918 and complained that Field appeared to be putting a young man through college rather than helping his step-brother Edward whose business had collapsed.[2]: 136 The African-American boy might have been Charles Keene, son of the woman who managed Field's boarding house at 110 Columbia Heights.[59]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Regarding the academicians who instructed Field a friend of his later wrote that he had studied "with inferior Paris painters."[6]

- ^ Brooklyn Life noted the comings and goings of Field and his mother between Brooklyn and Ogunquit in April 8, 1905, p. 24; November 4, 1905, p. 17; November 25, 1905, p. 30; April 14, 1906, p. 25; June 15, 1907, p. 28; October 12, 1907, p. 21); October 8, 1910, p. 18; June 24, 1911, p. 18; June 14, 1913, p. 16; July 25, 1914, p. 13; October 21, 1916, p. 15.)

- ^ The name Ardsley came from a country estate in the village of Kings Point in Great Neck, Long Island, owned by Field's father which was Field's mother's during her lifetime and which, on her death, was divided between Field and his brother Herbert.[21][22] Kings Point was disguised as "West Egg" in F. Scott Fitzgerald's book The Great Gatsby.[23]

- ^ Established in 1904 by Field's neighbors in Brooklyn Heights, the Little Italy Settlement House was located in the Red Hook section of Brooklyn. In addition to providing art instruction, Field was an associate member of the settlement house association.[25][26][27]

- ^ Although Field is reported to have started the school in 1911, there are no news reports of its existence until 1914.[2]: 33 [3][7]: 89–90 [28]

- ^ Kuniyoshi and Schmidt married while they were residents; Rogo and Hirsch married a few years later. Field permitted Kuniyoshi and Schmidt to live at Ardsley Studios rent-free.

- ^ Arts and Decoration (New York : Hewitt Publishing Co.) began in 1910 and continued until 1942. In 1918 it absorbed Art World (and was known as "The Art World and Arts and Decoration", reverting to "Arts and Decoration" in 1919).[33]

- ^ As noted below, the newspapers.com subsidiary of Ancestry.com lists 146 articles on Field from 1903 to 1922 all from the same publication, Brooklyn Life, which covered the activities of "Brooklyn's upper crust."[34]

- ^ Rogo gave only surnames supposing the reader to identify the artists without their give names.

- ^ For example, the Blue Book listed members of the Field family in 1903, 1914, and 1919.[53][54][55] The newspapers.com subsidiary of Ancestry.com lists 146 articles on Field in Brooklyn Life from 1903 to 1922.

- ^ The Field estate in Great Neck was subsequently purchased, first by George M. Cohan in 1915, and later by Walter Annenberg in 1943.[57][58]

- ^ The term "companions," used to describe the boys and young men in Field's life, appears in Field's entry in the U.S. Census report for 1920.[59]

References[edit]

- ^ a b "Men High in Art World Pay Tribute to Memory of Hamilton Easter Field, Artist and Art Critic" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 1922-04-16. p. C3. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Wendy Jeffers (2011). "Hamilton Easter Field: The Benefactor from Boston". Archives of American Art Journal. 50 (1–2). Washington, DC: Smithsonian Institution: 26–37. doi:10.1086/aaa.50.1_2.23025821. S2CID 192873432.

- ^ a b c d e f William Green (Summer 1983). "Hamilton Easter Field (1873-1922)". Impressions (8). Japanese Art Society of America. ISSN 1095-2136. JSTOR 42597617.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Colin B. Burke (2014). Information and Intrigue: From Index Cards to Dewey Decimals to Alger Hiss. MIT Press. ISBN 978-0-262-02702-1.

- ^ a b c "The Picture Exhibition of Hamilton Easter Field". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1905-03-16. p. 21.

- ^ a b c d e f Elsa Rogo (1934). [Exhibition Catalog:] Hamilton Easter Field Art Foundation collection of paintings and sculpture (PDF). College Art Association.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Doreen Bolger (1988). "Hamilton Easter Field and His Contribution to American Modernism". American Art Journal. 20 (2). New York: Kennedy Galleries, Inc.: 78–107. doi:10.2307/1594508. JSTOR 1594508.

- ^ a b c d "Hamilton Easter Field" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 1922-04-10. p. 6. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ "Great Multitude at the Deschanel Wedding; President of the French Chamber of Deputies Sets a New Fashion for Paris Bridegrooms—Beautiful Sculpture at the Luxembourg; a Promising Brooklyn Painter" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1901-03-03. p. 6. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

In one of the old houses, after mounting up seven flights, the last one a spiral staircase leading up to heaven, you knock at one of the many doors, and you are welcomed by a Brooklynite, Hamilton Easter Field, who has chosen to make for himself an artistic paradise in Paris. The walls are covered with old tapestries, over which are hung pictures of all kinds, and furniture which could fill a mansion has found house room. All the chests of drawers, which are most curious in themselves, are filled with the rarest of engravings of all schools and the most beautiful collection of Japanese prints. Around the room are hundreds of low, dwarf cases filled with precious books on art. The titles of the books would take a week to read. There is a piano, a harmonium, an engraving press and a corner of the immense studio, separated by precious tapestries doing the service of curtains, is turned into a kitchen, in which are hung several pictures by old masters.

- ^ "Japanese Prints Sold; First Sale of the Field Collection Bring $1,617". New York Times. 1907-04-23. p. 2.

This is the first of a series of sales of Mr. Field's collection, but no others will be given this season. The collection was made during ten years which the collector spent in Paris.

- ^ "Hamilton Easter Field, 1920". "United States Passport Applications, 1795-1925," database with images, FamilySearch; citing Passport Application, New York, United States, source certificate #19696, Passport Applications, January 2, 1906 - March 31, 1925, 1168, NARA microfilm publications M1490 and M1372 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,638,301. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ Linda Nochlin (1997-03-06). "The Vanishing Brothel". London Review of Books. 19 (5): 3–5.

- ^ a b "Pablo Picasso | Pipe Rack and Still Life on a Table | The Met". Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ^ "Picasso: A Cubist Commission in Brooklyn; The Met". Retrieved 2023-09-17.

- ^ "The Travelers". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1909-10-16. p. 16.

- ^ "Settlement Work Begun by Heights Society Folk". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1904-10-22. p. 15.

- ^ "Social Notes". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1905-02-18. p. 7.

- ^ "Matters of Art Interest". New York Times. 1905-03-15. p. 7.

- ^ "A Clever Young Artist". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1912-05-24. p. 6.

- ^ "Exhibit of Paintings by Athos Casarini". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1912-06-01. p. 17.

- ^ a b "Surrogate's Proceedings, Jamaica, L.I. July 22" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. 1897-07-22. p. 8. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ "Local History Notes from the Great Neck Library: Welcome to the Great Neck Library's Local History Blog". Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ "Forbes Property Porn of the Week". Forbes. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ "Little Italy House an Assured Success". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1905-06-18. p. 3.

- ^ "Boys and Girls Run Their Own Neighbor House". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1939-12-15. p. 26.

- ^ "Art and Artists" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1905-07-16. p. 9. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ "Little Italy House an Assured Success". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1904-10-31. p. 6.

- ^ a b "The Travelers". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1914-07-25. p. 13.

Mr. Hamilton Easter Field, who has been at Watkins Glen, N.Y., has gone to Thurnscoe, Ogunquit, Me., to open his summer painting school. His mother, Mrs. Aaron Field of 106 Columbia Heights, will leave Watkins Glen next week for Ogunquit.

- ^ "Hamilton Easter Field, 1917-1918". "United States World War I Draft Registration Cards, 1917-1918," database with images, FamilySearch; citing York County no 2, Maine, United States, NARA microfilm publication M1509 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,654,022. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ "Japanese Prints and Modernistic at the Ardsley". Evening World. New York, N.Y. 1917-01-18. p. 12.

- ^ "HAMILTON E. FIELD DEAD.: Noted Art Critic Was Authority on Japanese Prints". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 1922-04-11. p. 6.

- ^ Hamilton Easter Field (1919-11-15). "Art New and Old in Current Shows". Arts and Decoration. New York: Joseph A. Judd Company. Retrieved 2016-05-15.

Editor's Note: Arts & Decoration is pleased to introduce Hamilton Easter Field as reviewer of the current art exhibitions. His many years of study abroad, during which he visited all the principal museum of Europe, his impartiality and absolute sincerity have given his writings an authority both among conservatives and radicals.

- ^ "Arts and Decoration archives". University of Pennsylvania Library. Retrieved 2016-09-01.

- ^ "Brooklyn Life Magazine, 1890-1931". Brooklynology, Brooklyn Public Library. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ "Woman's Club". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1902-01-31. p. 34.

- ^ "The Looker-On". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1904-02-20. p. 6.

- ^ "Studio of This Artist Has Superb River View". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1905-03-19. p. 19.

- ^ "Very Artistic Musicals Given at Mrs. Aaron Field's". Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, N.Y. 1911-11-23. p. 6.

- ^ "What is Doing in the World of Art, Artists and Art Dealers". Sun. New York, New York. 1913-11-16. p. 65.

- ^ "News and Activities in the World of Art". Sun. New York, New York. 1917-12-30. p. 56.

- ^ "Detailed description of the Forbes Watson papers, 1840-1967, bulk 1900-1960". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-09-18.

- ^ Garnett McCoy (1980). "Lloyd Goodrich Reminisces: Part I". Archives of American Art Journal. 20 (3). University of Chicago Press and Archives of American Art: 2–18. JSTOR 1557291.

- ^ "Hamilton Easter Field Papers, circa 1913-1966". Archives of American Art, Smithsonian Institution. Retrieved 2016-09-13.

- ^ American Art News, Vol. 20, no. 27. JSTOR. American Art News. 1922-04-15.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ "Two Worth-while Exhibitions by Brooklyn Men". Brooklyn Life. Brooklyn, New York. 1912-03-02. pp. 13, 20.

- ^ a b c d e f Tunis Garret Bergen (1915). Genealogies of the State of New York: A Record of the Achievements of Her People in the Making of a Commonwealth and the Founding of a Nation. Lewis Historical Publishing Company. pp. 1321–1323.

- ^ "Obituary Notes" (PDF). Sun. New York. 1897-04-11. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

Aaron Field died suddenly Friday night (Apr 9) at the home of his sister, 135 Willow street, Brooklyn. He had arranged to sail for Europe with his wife yesterday. Mr. Field was born in Brooklyn sixty-eight years ago, and for years was employed in the dry goods house of Field, Merrit & Co., of which his father was the head. In 1868 the firm gave up the jobbing line and went into the auction and commission business, and later became the firm of Field, Chapman, Feaner & Co., of which Aaron Field was the head. He was a member of the Long Island Historical Society, the Saturday and Sunday Hospital Association, the Society of Friends, and was a trustee of the Bowery Savings Bank. He was married twice. He leaves a widow and four children.

- ^ "Aaron Field, 1860". "United States Census, 1860", database with images, FamilySearch. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ "Aron Field, Ward 01, Brooklyn, Kings, New York, United States". "New York State Census, 1865," database with images, FamilySearch; citing source p. 5, line 22, household ID 26, county clerk, board of supervisors and surrogate court offices from various counties. Utica and East Hampton Public Libraries, New York; FHL microfilm 1,930,202. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ "Anna Haviland Field, 26 May 1883". "New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949," database, FamilySearch; citing Death, Brooklyn, Kings, New York, United States, New York Municipal Archives, New York; FHL microfilm 1,323,782. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ "Henry Crowwell Field, 14 Nov 1885". "New York, New York City Municipal Deaths, 1795-1949," database, FamilySearch; citing Death, Brooklyn, Kings, New York, United States, New York Municipal Archives, New York; FHL microfilm 1,323,807. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ "Deaths" (PDF). Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. 1921-04-07. p. 15. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ Brooklyn Blue Book and Long Island Society Register. Brooklyn Life Publishing Company. 1903. p. 260.

- ^ Brooklyn Blue Book. Brooklyn Life Publishing Company. 1914. p. 276.

- ^ Brooklyn Blue Book. Brooklyn Life Publishing Company. 1919. p. 401.

- ^ New York (State). Commissioners of the Land Office (1917). Proceedings of the Commissioners of the Land Office for the Year 1917. Weed, Parsons and Company. p. 18.

- ^ "In the Region/Long Island: For George Cohan's Kings Point Villa, It's Not Over". New York Times. 1999-11-14. Retrieved 2016-08-24.

- ^ "decisions.courts.state.ny.us" (PDF). State of New York, Supreme Court, Nassau County. Retrieved 2016-09-07.

- ^ a b "Raymond E. Webber in household of William H Webber, York, York, Maine, United States". "United States Census, 1910," database with images, FamilySearch; citing enumeration district (ED) ED 274, sheet 14A, NARA microfilm publication T624 (Washington, D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,374,561. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

- ^ "E Hamilton Field, Brooklyn Assembly District 1, Kings, New York, United States". "United States Census, 1920," database with images, FamilySearch; citing sheet 2B, NARA microfilm publication T625 (Washington D.C.: National Archives and Records Administration, n.d.); FHL microfilm 1,821,143. Retrieved 2016-08-26.

See also[edit]

- Bolger, Doreen. "Hamilton Easter Field and His Contribution to American Modernism". The American Art Journal (volume 20, number 2, 1988) pages 78–107. Kennedy Galleries, Inc. JSTOR 1594508.

- Burke, Colin B. Information and Intrigue: From Index Cards to Dewey Decimals to Alger Hiss (MIT Press, 2014).

- Green, William. "Hamilton Easter Field (1873-1922)". Impressions (volume 8, Summer 1983). Japanese Art Society of America. ISSN 1095-2136. JSTOR 42597617.

- Jeffers, Wendy. "Hamilton Easter Field: The Benefactor from Boston". Archives of American Art Journal (volume 50, number 1–2, 2011) pages 26–37.)