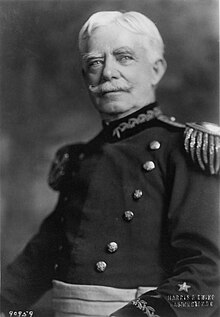

Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody

Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody | |

|---|---|

Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody | |

| Born | October 23, 1842 Highland County, Ohio |

| Died | January 1, 1933 (aged 90) Interlaken, New York |

| Allegiance | |

| Service/ | |

| Years of service | 1866–1904 |

| Rank | |

| Commands held | Chief, Weather Bureau

Chief Signal Officer, United States Volunteers Chief Signal Officer, U.S., in Cuba |

| Battles/wars | Spanish–American War |

| Relations | Ann E. Dunwoody (great-granddaughter) |

| Other work | Vice President, American DeForest Wireless; Inventor of the carborundum radio detector; President, Aztec Copper Company |

Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody (October 23, 1842 – January 1, 1933) was an American army officer, businessman, and inventor. Known in his own time for his work with the Army's Weather Bureau, he invented the carborundum radio detector in 1906. It was the first practical mineral radio wave detector and the first commercial semiconductor device.

Army career[edit]

Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody was born October 23, 1842, in Highland County, Ohio to William Dunwoody and Sarah Murphy. He entered the United States Military Academy as a cadet September 1, 1862, and was appointed second lieutenant, 4th Artillery after graduating in 1866. He spent much of his career in weather forecasting with the Signal Office, working as chief weather forecaster and creating a system of distributed storm warnings.[1] In 1883 he wrote a book on Weather Proverbs,[2] still an often quoted work on the subject.[3]

With the outbreak of the Spanish–American War he organized the Volunteer Signal Corps, serving as Chief Signal Officer, United States Volunteers, as a colonel, from May 20, 1898, to July 20, 1898, when he retired from volunteer service to return to regular duty in the Signal Corps. He served as Chief Signal Officer in Cuba from 1898 to 1901, overseeing the construction of telegraph lines on the island.

After May 1901 he was Acting Chief Signal Officer, Washington and supervised the installation of wireless stations along the Pacific coast, his first direct involvement with wireless.

In August 1902 while serving as the Signal Officer, Department of the East, Governors Island, he accepted a bid from the DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company for connecting Fort Wadsworth and Fort Hancock by wireless, replacing the telegraph cables connecting the forts and headquarters on Governor's Island which had frequently been severed by anchors and current.[4] The stations were first tested on March 11, 1903. Dunwoody oversaw the tests at Fort Wadsworth, and C. G. Tompkins, general manager of the DeForest company was in charge of operations at Fort Hancock. The tests were considered a success, and secured future Army contracts for company founder Lee deForest.

On October 21, 1903, Colonel Dunwoody left the office of Chief Signal Officer and assumed command of the signal post at Fort Myer. He was promoted to Brigadier General July 6, 1904 and retired at his own request the following day.

Dates of rank[edit]

| Second Lieutenant | First Lieutenant | Captain | Major |

|---|---|---|---|

|

|||

| June 18, 1866 | February 5, 1867 | June 17, 1889 | December 18, 1890 |

| Lieutenant Colonel | Colonel (Volunteers) | Colonel | Brigadier General |

|

|

| |

| March 15, 1897 | June 1, 1898 | July 8, 1898 | July 6, 1904 |

Carborundum radio wave detector[edit]

Dunwoody and Lee deForest had a good working relationship, and on July 27, 1904, it was announced that Dunwoody would be a vice president of the DeForest Wireless Telegraph Company, specifically in charge of dealings with the military.[5]

In March 1906 Dunwoody and deForest teamed with Alexander Graham Bell using Bell's tetrahedral kites to raise aerials. They were able to transmit and receive between the Washington Navy Yard and the DeForest station in New Jersey. By April 6 they had sent and received a message from Glengarriff Harbor, County Cork, Ireland, and Brooklyn, New York.

The next day the DeForest company lost a nearly three-year legal battle with the National Electric Signaling Company (NESCO), receiving a fine and an injunction against using the "spade detector", their most important detector, because it was too similar to the electrolytic detector patented by Reginald Fessenden.

DeForest had anticipated losing his rights to the detector, and had set out to find a replacement. He had been working on the first triode vacuum tube, the audion, but it was not sufficiently developed to replace the spade detector.

Earlier in 1906 Dunwoody had found that the mineral carborundum worked as a detector of radio waves. An extremely hard compound of silicon and carbon, carborundum was first produced artificially by Edward Goodrich Acheson in 1890 during his attempts to produce artificial diamonds. It exists in nature only rarely, in certain meteorites.

Dunwoody filed for a patent for the carborundum detector on March 28, 1906.[6] His patent drawings show many possible configurations for the detector; most were versions of detectors already in use, substituting carborundum for one of the components. Dunwoody and deForest settled on a version which was essentially two wedges of the mineral placed in contact with each other. It worked, but not well. deForest hired Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, who had served as an expert witness for him in patent cases, and who had himself been testing mineral radio wave detectors, to improve the carborundum detector. He found that increasing the contact pressure and adding an electrical bias to the detector improved its performance greatly. It saved the company, but the injunction was costly, and in November 1906 deForest parted ways with the company, taking with him $1000 for his patents and all rights to the audion tube, which the board considered worthless.

After DeForest[edit]

Dunwoody stayed with the company, now reorganized as the United Wireless Telegraph Company, for a brief time. In 1912 United Wireless, weakened by scandal and patent disputes, was absorbed by the American Marconi Company. Properly configured, carborundum makes a very sensitive detector, and by now had become a favorite of wireless operators. Marconi used it in the first successful commercial station to signal across the Atlantic, between Louisbourg, Nova Scotia and Letterfrack, Ireland in 1912.[7] It was replaced only gradually by the simpler galena and cat whisker detector of Greenleaf Whittier Pickard, and made a resurgence in the 1920s thanks to the efforts of Acheson's Carborundum Company.

Dunwoody remained active in research, patenting electronic devices as well as armaments. By 1911 he was president of the Aztec Copper Company, managing small claims near Organ, New Mexico. He died January 1, 1933, in Interlaken, New York.

Legacy[edit]

Dunwoody's great grandfather, James Dunwoody, served as a private in the 8th company of the Cumberland County Militia during the Revolutionary War, and several of his descendants had notable military careers. His son, Halsey Dunwoody, was the Assistant Chief of the Air Service during the First World War and one of the founders of American Airlines. His grandson, General Harold Dunwoody, served in World War 2, Korea and Vietnam, and his great granddaughter Ann E. Dunwoody would become the first female four-star general in the army.

The Brigadier General Henry Harrison Chase Dunwoody Monument and Park at Fort Eisenhower, Georgia commemorates his work in the Signal Corps and specifically his leadership in the reconstruction of the Cuban telegraph system after the Spanish–American War. The park, as well the Spanish–American War Monument and the Signal Corps Time Capsule, were previously located at Fort Monmouth, New Jersey and were relocated to Fort Gordon (now Fort Eisenhower) after Fort Monmouth was closed as part of the Base Realignment and Closure process in 2012. The bronze monument was newly dedicated at Fort Gordon and not moved from Fort Monmouth, but contains the same wording as a sign that was located at the original Dunwoody Park. H. H. C. Dunwoody's great-granddaughter, General Ann E. Dunwoody, spoke at the dedication.[8]

References[edit]

- ^ United States Military Academy. "Sixty-fourth Annual report of the Association of the Graduates of the United States Military Academy". OCLC 866192742.

{{cite journal}}: Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ Dunwoody, Henry Harrison Chase (1883-01-01). Weather Proverbs. Signal service notes, no. 9. Washington, D.C.: Government Printing Office.

- ^ Weeks, Linton (15 February 2014). "What We Might Learn From Snoring Weather Cats". NPR. NPR.org. Retrieved 2016-04-23.

- ^ "Wireless Telegraphy for Forts". New York Times. August 6, 1902.

- ^ "Government's Wireless Contract Arranged". Baltimore Morning Herald. July 27, 1904.

- ^ "Wireless-telegraph system". patents.google.com. 1906-03-23. Retrieved 2016-04-20.

- ^ Lee, Bartholomew (2009). "How Dunwoody's Chunk of 'Coal' Saved both de Forest and Marconi" (PDF). AWA Review (22): 5. Retrieved 20 April 2016.

- ^ "Fort Gordon receives, rededicates monuments". www.army.mil. Retrieved 2017-07-17.