Jet (gemstone)

| Jet | |

|---|---|

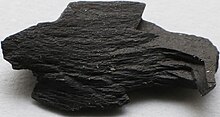

Sample of unworked jet, about 15 mm long | |

| General | |

| Category | Mineraloid |

| Formula (repeating unit) | Variable, but rich in carbon |

| Identification | |

| Color | Black, occasionally brown |

| Cleavage | None |

| Fracture | Conchoidal |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 2.5–4.0 |

| Streak | Brown |

| Specific gravity | 1.3–1.4 |

| Optical properties | Isotropic |

| Refractive index | 1.640–1.680 |

| Dispersion | None; opaque |

| Ultraviolet fluorescence | None |

| Common impurities | Iron, sulfur |

| References | [citation needed] |

Jet is a type of lignite,[1] the lowest rank of coal, and is a gemstone. Unlike many gemstones, jet is not a mineral, but is rather a mineraloid.[2] It is derived from wood that has changed under extreme pressure.

The English noun jet derives from the French word for the same material, jaiet (modern French jais), ultimately referring to the ancient town of Gagae.[3] Jet is either black or dark brown, but may contain pyrite inclusions[4] which are of brassy colour and metallic lustre. The adjective "jet-black", meaning as dark a black as possible, derives from this material.

Origin

[edit]Jet is a product of decomposition of wood from millions of years ago, commonly the wood of trees of the family Araucariaceae.[5] Jet is found in two forms, hard and soft.[5] Hard jet is the result of carbon compression and salt water; soft jet may be the result of carbon compression and fresh water.[5] Despite the name they both occupy the same area of the Mohs scale with the difference being that soft jet is more likely to crack when exposed to changes in temperature.[6]

Properties

[edit]Jet is around 75% carbon and 12% oxygen with sulfur and hydrogen making up most of the balance.[7] Other elements are found at trace level and the exact ratios varying with the source; for example, Spanish jet contains more sulfur than Whitby jet.[7] Jet has a Mohs hardness ranging between 2.5 and 4 and a specific gravity of 1.30 to 1.34. The refractive index of jet is approximately 1.66. The touch of a red-hot needle should cause jet to emit an odour similar to coal.[8]

Jet may induce an electric charge like that of amber when rubbed.[7]

Jet is very easily cut using carving tools, but small pieces tend to break off, making it difficult to create fine details. It therefore takes an experienced lapidarist to execute more elaborate carvings.

Location

[edit]England

[edit]

The jet found at Whitby, in England, is the "Jet Rock"[9] unit of the Mulgrave Shale Member, which is part of the Whitby Mudstone Formation. This jet deposit was formed approximately 181 million years ago, during the Toarcian age of the Early Jurassic epoch.[10][11][12] Whitby Jet is the fossilized wood from species similar to the extant Chilean pine (Araucaria araucana).[13] The deposit extends throughout North York Moors National Park.[14]

Jet has also been found in Kimmeridge shale seams in Dorset.[15]

France

[edit]Jet was mined from a number of areas of France including Montjardin and Roquevaire.[16] Raw jet was also imported from Spain.[16] In the 18th century there was a jet working industry based around Sainte-Colombe-sur-l'Hers and La Bastide-sur-l'Hers but this declined with the start of the 19th.[16] An 1871 plan to import raw French jet into Whitby was unsuccessful due to its poor quality.[16]

Spain

[edit]The jet found in Asturias, the biggest deposit in northern Spain,[17] is of Late Jurassic (Kimmeridgian) age, about 155 million years old. Asturian jet is a perhydrous coal that suffered an anomalous coalification process and presents great material stability over long periods of time.[18] At the end of the Middle Ages, the trade of religious objects and amulets made of jet reached great development in Santiago de Compostela, with sales to pilgrims traveling the Camino de Santiago. However, the deposits were in Asturias, where simple objects such as beads and rosary beads were also made. Santiago de Compostela was the main sales point and the location of the workshops that produced artistic objects. Jet has also been extracted in the area of Utrillas, Gargallo, and Montalbán in the province of Teruel, although it is of lower quality than that from Asturias.[19]

United States

[edit]Native American Navajo and Pueblo tribes of New Mexico were using regionally mined jet for jewellery and the ornamentation of weapons when early Spanish explorers reached the area in the 1500s.[20] Today these jet deposits are known as Acoma jet, for the Acoma Pueblo. Enormous coal deposits characterize the San Juan Basin of New Mexico and this geology is closely related to jet deposits mined in the Henry Mountains of Utah[21] and the Front Range of El Paso County, Colorado.[22]

Other locations

[edit]Jet is also commercialized in Poland[23] and near Erzurum in Turkey, where it is known as oltu stone and is used to make prayer beads.[24]

History

[edit]

The earliest known worked jet object is a 10,000 BC model of a botfly larva, from Baden-Württemberg, Germany, found among the Venuses of Petersfels.[25]

Jet has been used in Britain since the Neolithic period[26] It continued in use in Britain through the Bronze Age where it was used for necklace beads.[26] Jet necklaces following the plate and spacer design may have been based on Gold lunula.[27] During the Iron Age jet went out of fashion until the early 3rd century AD in Roman Britain. The end of Roman Britain marked the end of jet's ancient popularity.[26]

Early archaeologists (particularly Victorian) often failed to distinguish between jet and other jet-like materials [28] In particular in southern Britain the material described as jet was often Kimmeridge Shale.[28][29] and some artifacts use more than one jet-like material.[30] For example the Pen y Bonc necklace combines two or three jet pieces with other dark material.[30]

Roman use

[edit]Whitby jet was a popular material for jewellery in Roman Britain from the 3rd century onward. There is no evidence for Roman jet working in Whitby itself,[26] rather it was transferred to Eboracum (modern York) where considerable evidence for jet production has been found.[31] The collection of jet at this time was based on beachcombing rather than quarrying.[26] It was used in rings, hair pins, beads, bracelets, bangles, necklaces, and pendants,[26] many of which can be seen in the Yorkshire Museum. Jet rings tended to follow the styles of existing metal rings although there were exceptions.[32] Jet pendants were carved cameo style with Medusa head being a popular theme.[33]

Stylistic similarities with jet items found in the Rhineland, and lack of any evidence for local manufacture, suggest that Eboracum-produced items were exported to that area.[34] One item that has been found around the Rhine but not in Britain are jet bracelets that feature grooves with gold inserts.[35]

The Roman period saw its use as a magical material, frequently used in amulets and pendants because of its supposed protective qualities and ability to deflect the gaze of the evil eye.[36] Pliny the Elder suggests that "the kindling of jet drives off snakes and relieves suffocation of the uterus. Its fumes detect attempts to simulate a disabling illness or a state of virginity."[37] It has been referenced by other ancient writers including Solinus[38] and Galen.

Viking use

[edit]Vikings made some use of jet including rings and miniature sculptures of animals with snakes being a prominent theme.[39] The source of the jet has not been confirmed although Whitby is the most likely possibility.[39]

Medieval

[edit]

Medieval jet use appears to have been largely limited to religious items such as crosses and Rosary beads.[40] During the period there was a belief that water drunk from jet bowls could help with labour.[41] A jet bowl held in the Museum of London may have been designed to allow for this.[42]

Jet became a valued costume accessory in the 16th century. Mary, Queen of Scots, owned jet buttons and clothes embroidered with jet beads.[43] Elizabeth I bought 1000 "black jet bugle drops" to embroider headdresses in 1587.[44] Anne of Denmark ordered a gown of "double burret" silk in June 1597 loaded with jet passementerie and 360 jet buttons. The gown was too heavy to wear and she ordered it to be remade with less jet.[45]

Victorian use

[edit]

Jet as a gemstone became fashionable during the reign of Queen Victoria.[46] It originally became fashionable in the 1850s after the queen wore a necklace of it as part of mourning dress for Princess Victoria of Saxe-Coburg and Gotha.[46] Later the Queen wore Whitby jet as part of her mourning dress while mourning the death of Prince Albert.[13][47][48]

In some jewellery designs of the period jet was combined with cut steel.[49]

Jet use was at its highest in the early 1870s and from there it declined.[50] From above 1000 workers in the trade Whitby was down to 300 by 1884.[50] While jet substitutes may have had an impact this appears to have been in a large part due to changes in fashion with Art Nouveau making little use of black jewellery.[50] As the numbers fell the remaining manufactures tended to stick with existing styles rather than attempting to adapt to new fashions resulting in demand falling further.[50] Making tourist trinkets kept a few jewellers in work, but by the end of World War II only three remained, and the industry died out completely with their deaths.[50]

20th century

[edit]In Whitby the Victorian tradition continued up until the aftermath of World War II.[50] Jet jewellery (both vintage and new) was then to remain out of fashion until the late '70s.[51] In the '80s there was a fashion for jet beads and antique jet jewellery started to rise in value.[52] New jewellers took up the production of jet jewellery.[52]

Jet substitutes

[edit]Glass was used as a jet substitute during the peak of jet's popularity.[53][54] When it was used in this way it was known as French jet or Vauxhall glass.[53][54] Ebonite was also used as a jet substitute and initially looks very similar to jet, but it fades over time.[55] In some cases jet offcuts were mixed with glue and molded into jewelry.[55]

Anthracite (hard coal) is superficially similar to fine jet, and has been used to imitate it. This imitation is not always easy to distinguish from real jet.

Some museums have produced reproductions of jet artefacts in epoxy resin.[56]

Authenticating jet

[edit]Unlike black glass, which is cool to the touch, jet is not cool, due to its lower thermal conductivity. When rubbed against unglazed porcelain, true jet will leave a brown streak, although bog oak, vulcanite, and lignite will do the same.[57]

When non destructive testing is required X-ray fluorescence spectroscopy combined with visual inspection (including under high magnification) and X-ray imaging is generally effective although it can be difficult to differentiate jet from lignite.[30]

Real jet, when placed in a flame, burns like coal and gives off a coal-like smell and produces soot. No other black "gemstone" behaves like this.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Neuendorf, K. K. E. Jr.; Mehl, J. P.; Jackson, J. A., eds. (2005). Glossary of Geology (5th ed.). Alexandria, Virginia: American Geological Institute. p. 344.

- ^ Holmes, Ralph J.; Crowningshield, Robert (1983). "Gemology". In Fyfe, Keith (ed.). The Encyclopedia of Mineralogy. Encyclopedia of Earth Sciences Series. Springer. pp. 168–187. doi:10.1007/0-387-30720-6_51. ISBN 978-0-87933-184-9.

- ^ Oxford English Dictionary (2nd edition) 1989, Oxford, Oxford University Press

- ^ Pye, K. (1985). "Electron microscope analysis of zoned dolomite rhombs in the Jet Rock Formation (Lower Toarcian) of the Whitby area, U.K.", Geological Magazine, volume 122, issue 3, pp. 279–286, Cambridge University Press, doi:10.1017/S0016756800031496

- ^ a b c Muller, Helen; Muller, Katy (2009). Whitby Jet. Shire publications. p. 5. ISBN 978-0-7478-0731-5.

- ^ Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 4. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ a b c Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 2. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ Richard T. Liddicoat, Jr. Handbook of Gem Identification 1989 GIA press, 12 ed. pg 192

- ^ Hemingway, John Edwin (1933). "Whitby jet and its relation to Upper Lias sedimentation in the Yorkshire basin". White Rose eTheses Online; PhD thesis, University of Leeds.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: postscript (link) (See Upper Lias.) - ^ Thibault, N.; Ruhl, M.; Ullmann, C.V.; Korte, C.; Kemp, D.B.; Gröcke, D.R.; Hesselbo, S.P. (2018). "The wider context of the Lower Jurassic Toarcian oceanic anoxic event in Yorkshire coastal outcrops, UK" (PDF). Proceedings of the Geologists' Association. 129 (3): 372–391. Bibcode:2018PrGA..129..372T. doi:10.1016/j.pgeola.2017.10.007. S2CID 55984383.

- ^ Cope, J. C. W. (2006). Jurassic: the returning seas - plate 26 and page 339 of Brenchley, P. J. and Rawson P. F. (editors) (2006) The Geology of England and Wales, 2nd edition, London, The Geological Society

- ^ Gradstein, F.M.; Ogg, J.G.; Schmitz, M.D.; Ogg, G.M., eds. (2012). The Geologic Timescale 2012. Elsevier. p. 765. ISBN 978-0-44-459390-0.

- ^ a b Oliver, N., 2012, A History of Ancient Britain, Phoenix Paperback, ISBN 978-0-7538-2886-1

- ^ Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 10. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ Watts, S; Pollard, A.M; Wolff, G.A (1997). "Kimmeridge Jet-A Potential New Source for British Jet". Archaeometry. 19 (1): 125–143. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4754.1997.tb00793.x.

- ^ a b c d Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. pp. 112–113. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ Ward, Gerald W. R. (2008). The Grove Encyclopedia of Materials and Techniques in Art. Oxford University Press. p. 307. ISBN 978-0-19-531391-8.

- ^ Suárez-Ruiz, Isabel; Iglesias, M. J.; Jiménez Bautista, Amalia; Domínguez Cuesta, María José; Laggoun-Défarge, F. (2006). "El azabache de Asturias: características físico-químicas, propiedades y génesis". Trabajos de Geología. 26. ISSN 1988-5172.

- ^ Calvo Rebollar, Miguel (2023). "La reina Victoria y míster Goodyear. Apogeo y ocaso del azabache de Teruel". Naturaleza Aragonesa (40): 12–17.

- ^ From The Rio To The Sierra: An Environmental History Of The Middle Rio Grande Basin (PDF). p. 103.

- ^ Minerals and Mineral Localities of Utah (PDF). UTAH GEOLOGICAL AND MINERAL SURVEY. p. 90.

- ^ "Jet from El Paso Co., Colorado, USA". www.mindat.org. Retrieved 2019-01-25.

- ^ Finlay, Victoria. Jewels: A Secret History (Kindle Location 1035). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "While there is no source of jet anywhere near southwestern Turkey, it can be found in western Anatolia near Erzurum, where there are about six hundred family-run mines in the mountains. They call it oltu-tasi and it is the material from which Muslim prayer-beads are made. Finlay, Victoria. Jewels: A Secret History (Kindle Locations 1054-1056). Random House Publishing Group. Kindle Edition.

- ^ "Venus figures from Petersfels". Archived from the original on 29 September 2016. Retrieved 9 August 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f Allason-Jones, Lindsay (1996). Roman Jet in the Yorkshire Museum. The Yorkshire Museum. pp. 8–11. ISBN 0-905807-17-0.

- ^ Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 20. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ a b Muller, Helen; Muller, Katy (2009). Whitby Jet. Shire publications. pp. 7–8. ISBN 978-0-7478-0731-5.

- ^ Brück, Joanna; Davies, Alex (2018). "The Social Role of Non-metal 'Valuables' in Late Bronze Age Britain". Cambridge Archaeological Journal. 28 (4): 665–688. doi:10.1017/S095977431800029X. hdl:1983/bfc58ed6-3871-4e03-aa74-a27c6b815d94. S2CID 165436341.

- ^ a b c Sheridan, Alison; Davis, Mary (1998). "The Welsh 'jet set' in prehistory: a case of keeping up with the Joneses?". Prehistoric Ritual and Religion. Sutton. pp. 148–162. ISBN 0-7509-1598-6.

- ^ Ottaway, P., 2004, Roman York, Tempus: Stroud ISBN 978-0-7524-2916-8

- ^ Johns, Catherine (1996). The Jewellery of Roman Britain Celtic and classical Traditions. Routledge. pp. 69–70. ISBN 978-0-415-51612-9.

- ^ Johns, Catherine (1996). The Jewellery of Roman Britain Celtic and classical Traditions. Routledge. pp. 106–107. ISBN 978-0-415-51612-9.

- ^ Muller, Helen; Muller, Katy (2009). Whitby Jet. Shire publications. pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-7478-0731-5.

- ^ Johns, Catherine (1996). The Jewellery of Roman Britain Celtic and classical Traditions. Routledge. pp. 120–121. ISBN 978-0-415-51612-9.

- ^ Henig, M., 1984, Religion in Roman Britain, London, BT Batsford Ltd ISBN 978-0-312-67059-7

- ^ Pliny the Elder. Natural History (trans. Bostock, J., Riley, H. T.). London: Taylor and Francis. 1855. Chapter 36

- ^ Caius Julius Solinus (2013). "DE MIRABILIBUS MUNDI CAPITULA VII–XXIV". Archived from the original on 2013-02-06. Retrieved 2013-10-31.

- ^ a b Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. pp. 25–26. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. pp. 27–28. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ French, Katherine L (2021). Household Goods and Good Households in Late Medieval London Consumption and Domesticity After the Plague. University of Pennsylvania Press, Incorporated. p. 141. ISBN 978-0-8122-5305-4.

- ^ Gilchrist, Roberta (2012). Medieval Life Archaeology and the Life Course. Boydell Press. p. 141. ISBN 978-1-84383-722-0.

- ^ Alexandre Labanoff, Lettres de Marie Stuart, vol. 7 (London: Dolman, 1844), pp. 230-238.

- ^ Janet Arnold, Queen Elizabeth's Wardrobe Unlock'd (Maney, 1988), p. 205.

- ^ Jemma Field, 'Female dress', Erin Griffey, Early Modern Court Culture (Routledge, 2022), pp. 398-99.

- ^ a b Tolkien, Tracy; Wilkinson, Henrietta (1997). A Collector's Guide to Costume Jewelry Key Styles and how to recognize them. Firefly Books. p. 52. ISBN 1-55209-156-2.

- ^ St. Clair, Kassia (2016). The Secret Lives of Colour. London: John Murray. pp. 276–277. ISBN 978-1-4736-3081-9. OCLC 936144129.

- ^ Phillips, Clare (1996). Jewelry from Antiquity to the Present. Thames and Hudson. pp. 148–150. ISBN 978-0-500-20287-6.

- ^ Clifford, Anne (1971). Cut-Steel and Berlin Iron Jewellery. Adams & Dart. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-239-00069-9.

- ^ a b c d e f Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. pp. 59–63. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 60. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ a b Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 64. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ a b "Jet necklace and black silk tie". Body arts. Pitt Rivers Museum. 2011. Archived from the original on 16 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b "Tiara". V&A Collections. Victoria and Albert Museum. Archived from the original on 15 February 2016. Retrieved 9 February 2016.

- ^ a b Phillips, Clare (1996). Jewelry from Antiquity to the Present. Thames and Hudson. p. 150. ISBN 978-0-500-20287-6.

- ^ Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 129. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.

- ^ Muller, Helen (1987). Jet. Butterworths. p. 132. ISBN 0-408-03110-7.