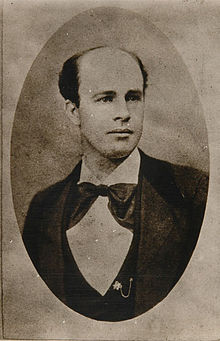

John Clum

John Philip Clum | |

|---|---|

John P. Clum c. 1880 | |

| Born | September 1, 1851 |

| Died | May 2, 1932 (aged 80) |

| Other names | Indian agent; first mayor of incorporated Tombstone, Arizona Territory; owner/editor, The Tombstone Epitaph |

| Known for | Only government agent to peacefully capture Geronimo |

| Spouse(s) | Mary "Mollie" (Ware) Clum Belle (Atwood) Clum Florence A. (Baker) Clum |

John Philip Clum (September 1, 1851 – May 2, 1932) was an Indian agent for the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in the Arizona Territory. He implemented a limited form of self-government on the reservation that was so successful that other reservations were closed and their residents moved to San Carlos. Clum later became the first mayor of Tombstone, Arizona Territory, after its incorporation in 1881. He also founded the still-operating The Tombstone Epitaph on May 1, 1880. He later served in various postal service positions across the United States.

Early life[edit]

John Clum was born on a farm near Claverack, New York, US. His parents were William Henry and Elizabeth van Deusen Clum of Dutch and German descent; he had five brothers and three sisters: Henry W. Clum, Jane E. Clum, Cornelia Clum, Sarah E. Clum, George A. Clum, Robert A. Clum, Cornelius N. Clum, and Alfred Clum.[1]

In September, 1867, he entered the Hudson River Institute (later known as Claverack College), a military academy in Claverack, New York. He also attended religious services at the Dutch Reformed Church. In September, 1870, he enrolled at Rutgers College. He obtained a classical education, studying among other subjects Latin, Greek, Mathematics (including algebra), Natural History (including physiology) and Rhetoric. He was a member of Rutgers' football team. Although Clum was on the team, he did not play in the first intercollegiate game between Rutgers and Princeton on November 6, 1869, but played in the second game in the fall of 1870.[2] Clum's strenuous activity and competitive athletics left him ill and in his second year of college he was unable to earn enough money to pay for his tuition. He returned to his father's farm in the summer of 1871.

Clum read in a newspaper story that the federal War Department in Washington, D.C. was organizing a meteorological service. He applied for and was inducted into the US Army Signal Corps on September 14, 1871, with the rank of Observer Sergeant. Two weeks later he was dispatched to Santa Fe, New Mexico, where he became a weather observer.[2]

Clum was first married on Nov. 8, 1876, in Delaware County, Ohio to Mary "Mollie" Ware. Mary died on Dec. 18, 1880, in Tombstone, Arizona, of fever, about one week after giving birth to a daughter named Bessie. Mary is buried in Boot Hill at Tombstone.[3][4] John Clum was married a second time on Feb. 6, 1883, in the District of Columbia, to Belle Atwood.[5] Clum was married a third and final time on Oct. 24, 1914, in New York City, New York to Florence A. Baker.[6][7][8][9][10]

Indian Agent[edit]

President Ulysses S. Grant established the San Carlos Reservation on December 14, 1872.[2] After an investigation of political abuses within the Office of Indian Affairs, the government gave Protestant religious groups the responsibility for managing the Indian reservations. The Dutch Reformed Church was given charge of the San Carlos Reservation. They sought out a candidate at Rutgers to run the reservation and were connected with Clum. Clum knew that a number of Indian Agents had already come and gone. Some Indian agents sought the position only as a means to line their own pocket, selling government-supplied food and clothing and keeping the profits for themselves.[2]

The office was very political, as the military commanders and civilian agents competed for control over the reservation and the money associated with the responsibility. The Apaches, who were supposed to be fed and housed by their caretakers, rarely saw the results of the federal money and suffered as a result. Soldiers and their commanding officers sometimes brutally tortured or killed the Indians for sport. On February 26, 1874, under these difficult conditions, Clum accepted a commission as Indian Agent for the San Carlos Apache Indian Reservation in the Arizona Territory.[2]

He arrived at the San Carlos Reservation on Tuesday, August 4, 1874. The very next day Apache scouts presented him with the severed head of Cochinay, a Tonto Apache renegade they had tracked down and killed.[2] He inherited a legacy of violence and mayhem, and a military presence which showed both animosity toward the Indians and disdain for the civilian Indian Agents.[2]

To the distant politicians in Washington D.C., all Indians were alike. They did not give consideration to the different tribes, cultures, customs and language. They also ignored prior political differences and military alliances. They tried to apply a "one-size-fits-all" strategy to deal with the "Indian problem". As a result, friends and foes were forced to live in close proximity to one another.[11]

Implements self-government[edit]

During Clum's tenure at San Carlos, he treated the Apaches as friends, established the first Indian Tribal Police and a Tribal Court, forming a system of Indian self-rule.[11] The Apaches nicknamed him "Nantan Betunnikiyeh", "Nantan", meaning boss or leader, "Betunnykahyeh" meaning high-forehead, or "Boss With The High Forehead", referring to his baldness. Clum encouraged them to take up the peaceful pursuits of farming and raising cattle.

The Army disliked Clum's actions, as it prevented them from raking off part of the funds that passed through the reservation.[11] Clum tired of the Army's constant meddling in his management of the reservation and the lack of support from the Indian Bureau, the very people who a short time previously had sought him out specifically as a man who would make a good Agent.[12]

Moves Chiricahua tribe[edit]

In September 1872, Cochise negotiated a Chiricahua Reservation for his people from the Dragoon Mountains on the west to the Peloncillo Mountains on the east. It included the Chiricahua Mountains and ran south to the Mexican border. On December 14, 1872, President Ulysses Grant issued an Executive Order establishing the Chiricahua Reservation in the southeastern Arizona Territory encompassing the Chiricahua Mountains, Mexico–United States border, and New Mexico Territory border.[13][14] Some members of the tribe continued raiding into the Mexican states Sonora and Chihuahua. Governor Pesqueira of Sonora complained bitterly about the raids, and General Crook tried to figure out how to force the relocation of the raiders to the San Carlos Reservation. Thomas J. Jeffords, who was Indian Agent to the reservation, lost influence when Cochise died on June 8, 1874.

In 1876 Jeffords was relieved of his responsibility and on May 3 the government ordered Clum to transfer the Chiricahuas to San Carlos.[15] After waiting in vain for military reinforcements to help with the move, Clum began relocating the tribe in early June. Cochise's sons Taza and Naiche agreed to the move and killed several Chircahuas, including Eskinya, Cochise's trusted ally, when he insisted they go to war. The Nednhi Chirica led by Juh also requested transfer. Clum granted them three days to round up their kinsmen. They used that time to elude the cavalry and flee south. Of the more than 1,000 Chiricahuas enumerated in Jeffords' infrequent censuses, only 42 men and 280 women and children accompanied Clum north.

The firing of Jeffords and the abolition of the Chiricahua Reservation in southeastern Arizona drove the Chiricahuas deeper into Mexico or over to the Ojo Caliente Reservation in the New Mexico Territory. In April 1877 the Interior Department ordered Clum to remove the bands at Ojo Caliente to San Carlos as well. Victorio and the Chihenne Chiricahuas acquiesced at first.

Captures Geronimo[edit]

Geronimo, on the other hand, was defiant. Clum hid 100 of his Apache police in the commissary building at Ojo Caliente and on April 21, 1877, they surprised Geronimo, seizing his rifle and throwing him in shackles. Clum's success gave the US Army a black eye; it was the only time Geronimo was captured at gunpoint without a shot fired on either side. A total of 453 Chiricahuas, 100 from Geronimo's band and the rest under Victorio, reached San Carlos in late May. From the very beginning they quarreled with the other Apaches confined there.

Clum resigns[edit]

Clum's feuds with the military escalated. Faced with superior officers who strongly disagreed with his methods, dogged by an uncaring Indian Bureau administration and under constant harassment by the Army, Clum was frustrated. He left his post as Indian Agent at noon on July 1, 1877, nearly three years after he had arrived.[11] His successor freed Geronimo and his men, leading to fifteen years of bloodshed and Indian wars until Geronimo was re-captured by General Miles on September 4, 1886, finally ending the Indian Wars.[11] Throughout his life, Clum believed that his work among the Apache was the finest and noblest work he had ever done.[2]

He was replaced by a series of agents who were renowned for their corruption. Two months later, Victorio, Loco, and 308 other Chiricahuas bolted for New Mexico, killing twelve ranchers before surrendering at Fort Wingate in early October.

Buys newspaper[edit]

Clum and his wife moved to Florence, Arizona Territory and bought a weekly newspaper, the Arizona Citizen then operating in Tucson, but he moved it to Florence. For the next two years he published editorials criticizing "the Army of Arizona and the political double-crossers in Washington".[12]

Life in Tombstone[edit]

After silver was discovered in Tombstone in 1877, Clum moved to Tombstone and began publication on Saturday, May 1, 1880 of The Tombstone Epitaph. He organized the "Anti-Chinese League",[17] and a "Vigilance Committee" to end lawlessness in Tombstone, and his association with that group helped get him elected as Tombstone's first mayor under the new city charter of 1881. While mayor he became lifelong friends with Wyatt Earp and became one of his greatest supporters. In December 1880, his wife Mary had a daughter Elizabeth, called Bessie, but Mary died soon after on December 18, 1880. Elizabeth was sickly and died the following summer.[18]: 117 [19]

After the gun battle of October 26, 1881 in a vacant lot adjacent to the home and studio of photographer Camillus S. Fly, Ike Clanton filed murder charges and after a month-long preliminary hearing, Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer ruled the men had acted within the law.[20] Clum later observed,

There had been a lot of talk about the justification of the fight. But the Earps were officers of the law and I could see no reason why an officer should wait until he was fired upon two or three times before opening up himself. Wyatt Earp told me afterward he could have killed Ike Clanton. Ike, Wyatt said, drew back and motioned he was not in it. He called to Ike. 'Get in this, Ike, or get out!' and Ike got out."[21]

Clum's friendship with the Earps and loyalty to the business leadership made him a target for the outlaw Cochise County Cowboys. On December 14, Clum was on a stagecoach to Benson to catch a train for Washington, D.C., where he planned to spend Christmas with his parents and son. He and his newspaper had consistently supported the lawmen. The stagecoach was fired upon by unknown assailants. The stage didn't carry any mail, cash, or silver, so robbery was an unlikely motive for the attack.[22] Driver Jimmie Harrington was able to outrun the attackers, but he soon had to stop to remove a lead horse that had been shot and was bleeding to death. Clum was certain the hold-up was cover for an attempt to kill him, so didn't reboard the stage, but walked until he found a horse he could borrow. He got to Benson the next day and then returned to Tombstone.[2][23][24][25]

Clum, Wells Fargo Agent Marshall Williams, Justice of the Peace Wells Spicer, mine owner E. B. Gage, attorney Tom Fitch, Oriental Saloon owner Lou Rickabaugh, and the Earps were also threatened.[26][12]

Clum described the attempted murder later. "Yes, I ran away from Tombstone," said Clum. "There were nine of us who were not supposed to get out of Tombstone alive. We received warnings, written in blood. We didn't pay a lot of attention to them at first, but after a few months it became most unbearable. They were picking us off one by one. We could never put our hands definitely on those who were doing it. I decided to settle elsewhere. They opened fire on me from both sides of the road. Three miles farther along the road a bullet tore through my coat and lead brought down my horse. I kept going without him."[21]

In January Virgil Earp was maimed in an assassination attempt and in March Morgan was murdered. On May 1, 1882, two years to the day after he started The Tombstone Epitaph, he sold it and left Tombstone.[12] The newspaper is still published today as a nationally distributed chronicle of the old west.

Later years and death[edit]

In 1898, Clum was appointed Postal Inspector for the District of Alaska and was commissioned to establish a territorial postal service there.[12] During a five-month period he traversed 8,000 miles (13,000 km) in the Alaskan territory, equipping existing post offices and establishing seven new post offices.[27]

While in Nome, Alaska in the summer of 1900, Clum met his old friends, Wyatt Earp and George W. Parsons. Earp was operating the Dexter Saloon at the time. Clum was later named postmaster for Fairbanks, Alaska, and served in that position until 1909. Caro, Alaska was named after his daughter Caro.[18]

John Clum left Alaska in 1909. Clum spent several years touring the country for the Southern Pacific Railroad, giving hundreds of lectures all over the country to promote tourism and passenger-use of the railroad. In 1928 he moved to Los Angeles, where he lived until his death in 1932 at age 80.[28]

In popular culture[edit]

Sam Melville was cast as Clum in the 1970 episode, "Clum's Constabulary", on the syndicated television anthology series, Death Valley Days, hosted by Dale Robertson. In the story line, Clum recruits an elite team of Apaches to aid the U.S. Cavalry in the Southwest but faces opposition within the white community. Tris Coffin was cast as Captain Loren Phillips and John Considine as Lago.[29]

Other television series or films with reference to Clum include:

- Frontier Marshal (1934) Russell Simpson played the part of "Editor Pickett".

- Frontier Marshal (1939) Harry Hayden played the part of Mayor Henderson.

- Tombstone, the Town Too Tough to Die (1942) Clum's role as mayor and newspaper editor was split, with Charles Halton playing "Mayor Dan Crane" and Emmett Vogan playing the part of "Editor John Clum".

- My Darling Clementine (1946) Roy Roberts played the part of the Tombstone Mayor.

- Walk the Proud Land (1956) Audie Murphy played Clum. Walk the Proud Land is the true story of Indian agent John Clum as told by Clum's son in the 1936 biography Apache Agent.

- Gunfight at the O.K. Corral (1957) Whit Bissell played Clum.

- The Life and Legend of Wyatt Earp, a TV series. (1960–1961) Stacy Harris played Clum.

- Hour of the Gun (1967) Larry Gates played Clum.

- Doc (1971) Dan Greenburg as Clum.

- Tombstone (1993) Terry O'Quinn played Clum.

- Wyatt Earp (1994) Randal Mell played Clum.

References[edit]

- ^ United States Federal Census records, Ancestry.com.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i "John P. Clum—The Early Years". Clum & Co. Old West Productions. Archived from the original on April 25, 2012. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ How did John Clum's first wife die?, Mark Boardman, True West, History of the American Frontier, https://truewestmagazine.com/how-did-john-clums-first-wife-die/ Archived November 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Ohio, County Marriages, 1774–1993, Ancestry.com

- ^ District of Columbia, Compiled Marriage Index, 1830–1921, Ancestry.com

- ^ New York, New York, Marriage License Indexes, 1907–2018, Ancestry.com

- ^ Ohio, County Marriages, 1774–1993, Ancestry.com.

- ^ District of Columbia, Compiled Marriage Index, 1830–1921, Ancestry.com.

- ^ New York, New York, Marriage License Indexes, 1907–2018, Ancestry.com.

- ^ United States Federal Census Records, Ancestry.com.

- ^ a b c d e Glauthier, Martha. "San Dimas Remembered – John P. Clum, Indian Agent". San Dimas Historical Society. Archived from the original on August 7, 2008. Retrieved February 2, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "John P. Clum". The Spell of the West. Retrieved April 12, 2013.

- ^ Grant, Ulysses S. (1912). "Chiricahua Reservation ~ December 14, 1872" [Executive Orders Relating to Indian Reserves, from May 14, 1855, to July 1, 1902]. Internet Archive. United States Government Printing Office. pp. 5–6. LCCN 34008449. OCLC 966752993.

- ^ "Territory of Arizona Map, 1876". United States Library of Congress. United States General Land Office. LCCN 99446141.

- ^ Grant, Ulysses S. (1912). "Executive Order of December 14, 1872 ~ Chiricahua Reservation Lands Restored to Public Domain - October 30, 1876" [Executive Orders Relating to Indian Reserves, from May 14, 1855, to July 1, 1902]. Internet Archive. United States Government Printing Office. p. 6. LCCN 34008449. OCLC 966752993.

- ^ Mark Boardman "How did John Clum's first wife die?" True West, History of the American Frontier. Retrieved 18 July 2020. This article uses the nickname Bessie for daughter. Elizabeth.

- ^ McCormack, Kara (2013). "Imagining "the Town too Tough to Die": Tourism, Preservation, and History in Tombstone, Arizona". American Studies Etds. University of New Mexico: 39.

- ^ a b Paula Mitchell Marks (1989). And Die in the West: the Story of the O.K. Corral Gunfight. New York: Morrow. ISBN 0-671-70614-4.[permanent dead link]

- ^ How did John Clum's first wife die?, Mark, Boardman, True West, History of the American Frontier, https://truewestmagazine.com/how-did-john-clums-first-wife-die/ Archived November 3, 2020, at the Wayback Machine . Retrieved 18 July 2020.

- ^ Linder, Douglas, ed. (November 30, 1881). "Decision of Judge Wells Spicer after the Preliminary Hearing in the Earp-Holliday Case". Famous Trials: The O. K. Corral Trial. Archived from the original on December 11, 2005. Retrieved February 11, 2011. From Turner, Alford (Ed.), The O. K. Corral Inquest (1992)

- ^ a b "Ex-Mayor Finds Town He Fled In Hail of Lead Quiet Now". Washington, D.C.: Evening Star. March 12, 1931. p. B-8.

- ^ "Mrs. Coyler's statement". The Old West History Net. July 2, 2011. Archived from the original on July 1, 2011. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ^ Thrapp, Dan L. (August 1, 1991). Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography, Volume 2: G-O. University of Nebraska Press. p. 619. ISBN 978-0803294196.

- ^ "Analysis of the GunFight". The Tombstone News. Archived from the original on March 4, 2016. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ^ Traywick, Ben T. "Wyatt Earp's Thirteen Dead Men". The Tombstone News. Archived from the original on November 9, 2017. Retrieved November 7, 2015.

- ^ A Citizen (December 19, 1881). "The Cow-boy Organ". Tombstone, Arizona: The Tombstone Epitaph. p. 1. Archived from the original on October 12, 2014.

- ^ "John Clum in Alaska". Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ "John Philip Clum, Gold Rush Postal Inspector". Smithsonian National Postal Museum. Archived from the original on July 31, 2018. Retrieved September 14, 2018.

- ^ "Clum's Constabulary on Death Valley Days". Internet Movie Database. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

Further reading[edit]

- John P. Clum, Tombstone Epitaph – 1950 Arizona Newspapers Association Hall of Fame

- John P. Clum, Indian Agent by Martha Glauthier, San Dimas Historical Society

- Nantan: The Life and Times of John P. Clum Volume 1 Claverack to Tombstone (2007) by Gary Ledoux / Trafford Publishing[self-published source]

- Nantan: The Life and Times of John P. Clum Volume 2 Tombstone to Los Angeles (2008) by Gary Ledoux / Trafford Publishing[self-published source]

- Wallace Clayton; Robert E. Love (2012). "The Life and Times of John P. Clum". The Tombstone Epitaph. Special Historical Edition. Tombstone, AZ. ISSN 1940-221X.

External links[edit]

- 1851 births

- 1932 deaths

- American people of Dutch descent

- People of the American Old West

- People from Claverack, New York

- People from Tucson, Arizona

- People from Fairbanks, Alaska

- People from pre-statehood Alaska

- Rutgers University alumni

- United States Indian agents

- American newspaper publishers (people)

- Cochise County conflict

- Claverack College alumni

- People from Tombstone, Arizona

- American people of German descent

- Burials at Forest Lawn Memorial Park (Glendale)

- People from Arizona Territory