List of Major League Baseball records considered unbreakable

A request that this article title be changed to List of MLB records considered unbreakable is under discussion. Please do not move this article until the discussion is closed. |

This article needs additional citations for verification. (March 2024) |

Some Major League Baseball (MLB) records are widely regarded as "unbreakable" because they were set by freak occurrence or under rules, techniques, or other circumstances that have since changed. Some records previously regarded as unbreakable have been broken and even re-broken.

Pitching[edit]

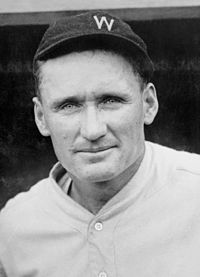

Most career wins – 511[edit]

Set by Cy Young, 1890–1911.[2][3][4] Highlights include five 30-win seasons and fifteen 20-win seasons.[5] The next closest player is Walter Johnson with 417, the only other player that reached 400.[6] The most wins by a pitcher who played his entire career in the post-1920 live-ball era is Warren Spahn's 363.

For a player to accomplish this, he would have to average 25 wins in 20 seasons just to attain 500. Since 1978, only three pitchers (Ron Guidry in 1978, Bob Welch in 1990, and Steve Stone in 1980[7]) have had one season with 25 wins.[8] Between 2000 and 2009, the Major League leader finished each year with an average of 21. Only four pitchers expected to be active in the 2024 season have even 200 wins—Justin Verlander with 257, Zack Greinke with 225, Max Scherzer with 214, and Clayton Kershaw with 210. The next active player on the list, Gerrit Cole, ended the 2023 season with 145.[9]

Most wins in a season – 60[edit]

Set by Charles Radbourn, in 1884,[10] with Jack Chesbro's 41 in 1904 historically regarded as the modern mark. In today's game of five-man rotations, pitchers do not start enough games to break the record. Miles Mikolas was the only pitcher to start 35 games in 2023, and only three pitchers in the 21st century have started more than 35 games in a season (Tom Glavine in 2002 and Roy Halladay and Greg Maddux in 2003, each with 36 starts).[11] Although relief pitchers often appear in more than the requisite number of games, they rarely record ten wins in a season, and the use of relief pitchers increases a starter's chance of a no decision, further limiting the ability to break the record. To put this record in further perspective, the last pitcher to win 30 games in a season was Denny McLain in 1968 and the last pitcher to win more than 25 games in a season was Bob Welch with 27 in 1990. The most wins in a season by any pitcher in the 21st century is 24, by Randy Johnson in 2002 and Justin Verlander in 2011.[12]

Most career complete games – 749[edit]

Set by Cy Young, 1890–1911.[3] Highlights of this record include: nine 40-complete-game seasons, eighteen 30-complete-game seasons[5] and completing 92 percent of his total career starts (an all-time record of 815).[3] The next closest player is Pud Galvin, who has 103 fewer complete games at 646. Among pitchers whose entire careers were in the live-ball era, the most is 382 by Warren Spahn.

For a player to accomplish this, he would have to average 30 complete games over 25 seasons to get to 750. Between 2000 and 2009, the Major League leaders in complete games averaged eight per season, and only two pitchers in the 21st century have had 10 complete games in any season (CC Sabathia with 10 in 2008 and James Shields with 11 in 2011).[13] In addition, only two pitchers other than Young have even started as many as 749 games—Nolan Ryan (773) and Don Sutton (756).[14] Among pitchers expected to be active in the 2024 season, the leader is Verlander with 26, followed by Kershaw with 25.[15]

The quest for any complete-game records, either over a career or over a single season, is further complicated by the drastic change in philosophy embraced by virtually all modern managers and pitching coaches, motivated in roughly equal parts by more advanced modern-day medical knowledge of the cumulative damage that pitching does to a hurler's arm, combined with a team front office's reluctance to see injuries to a pitcher in whom they have invested considerable financial capital in the form of a big contract. Another factor, arguably, is the greater reliance of managers and pitching coaches on sabermetrics—in this case, statistical data and analysis that generally show leaving a starter in longer leads to diminishing returns in terms of opposing batters allowed to reach base safely and score runs.[16] While even a few decades ago, a starting pitcher was expected to go out and attempt to pitch a complete game, with the manager going to his bullpen only if the starter ran into trouble or was injured or visibly tiring, the present-day norm is the starter is expected to give his manager six, or perhaps seven "quality innings", at which point the manager—who, along with the pitching coach, has been tracking the starter's pitch count—will normally lift him and bring in one or more middle-relief specialists to pitch the next several innings and form a bridge to the team's closer.[17] There are exceptions—a manager will leave a starter in who is working on a no-hitter or, sometimes, a shutout, or will let a starter continue if he is pitching particularly strongly and has not run up a high pitch count. But managerial caution is now a more dominant mode, particularly if a pitcher is coming off a recent injury or has had Tommy John surgery or any other major procedure done on his pitching arm.

These changes in philosophy have reduced the number of complete games in today's game to an even greater extent than in the first decade of the 21st century. Since Shields amassed 11 complete games in 2011, no pitcher has had more than 6 complete games in a season, with the two most recent to amass 6 being Chris Sale in 2016 and Sandy Alcántara in 2022. In 2018, all of Major League Baseball combined for 42 complete games, with no pitcher having more than 2. The 2019 season was similar in both respects, with 45 total complete games and no pitcher having more than 3.[18] In a 2019 story, Sam Miller of ESPN went so far as to say, "In your lifetime, you might very well see the last complete game."[19] In 2022, managerial caution reached an unprecedented new standard when Los Angeles Dodgers ace Clayton Kershaw was pulled while working on a potential perfect game.[20]

Most complete games in a season – 75[edit]

All-time record of 75 set by Will White in 1879; modern-era record of 48 set by Jack Chesbro in 1904. Sports Illustrated has said about this record, "Even if the bar is lowered to begin with the live-ball era (which began in 1920), the mark would still be untouchable." The most complete games recorded in a live-ball season is 33, achieved three times in all—twice at the dawn of that era by Grover Cleveland Alexander in 1920 and Burleigh Grimes in 1923, and also by Dizzy Trout in 1944, a season in which the player pool was severely depleted by military call-ups during World War II. Modern starters can expect to start about 34 games in a season while fully healthy.[13] The current active leader in complete games over an entire career is Justin Verlander with 26.

Most consecutive complete games in a season (since 1900) – 39; Most consecutive games without being relieved – 202[edit]

Both records were set by Jack Taylor, who pitched 202 consecutive games without being relieved from June 20, 1901, through August 13, 1906. The streak includes a total of 187 career starts (all complete games) and 15 relief appearances. The streak of 39 consecutive complete games (uninterrupted by a relief appearance) is a subset of the longer streak, lasting from April 15 through October 6, 1904.

Most career shutouts – 110[edit]

Set by Walter Johnson, 1907–1927.[21] Highlights include: eleven six-shutout seasons and leading the league in shutouts seven times.[22] The next closest player is Grover Cleveland Alexander, who has 90. As is the case for career wins and complete games, Warren Spahn, who retired in 1965, holds the record among pitchers whose entire careers were in the live-ball era, with 63.

For a player to tie Johnson's record, he would have to pitch five shutouts every season for 22 years.[21] Between 2010 and 2019, the Major League leader in shutouts finished each year with an average of three, and no pitcher has recorded more than two shutouts in a season since 2017. Also, adding the MLB-leading shutout totals for each season from 1992 through 2019 results in a total of 106, still short of Johnson's record.[23] The closest active player is Clayton Kershaw with 15.[24]

Most shutouts in a season – 16[edit]

Set first by George Bradley in 1876 and equaled by Grover Cleveland Alexander in 1916; live-ball era record of 13 set by Bob Gibson in 1968.[25]

Sam Miller of ESPN had this to say about a rhetorical suggestion that the live-ball record of 13 could be broken: "This is the stupidest suggestion yet. Thirteen shutouts clearly belongs in the anachronism pile." He pointed out that neither the National nor American League had 13 combined shutouts in the 2018 season, and no pitcher had more than one in that season.[26]

Most consecutive no-hitters – 2[edit]

Set by Johnny Vander Meer on June 11 and 15, 1938.[1] Despite holding this record, he finished his career with a 119–121 win–loss record.[1] The prospect of a pitcher breaking this record by hurling three no-hitters in a row is so unimaginable that LIFE argued "it's easier to imagine someone hitting in 57 straight games or bashing 74 home runs in a season or ending the season with a 1.11 ERA."[1] Ewell Blackwell came the closest to matching Vander Meer after following up a no-hitter with eight no-hit innings in 1947.[27] In 1988, Dave Stieb of the Toronto Blue Jays had consecutive no-hitters going with two outs and two strikes in the ninth; both were broken up by singles.[28] Between 2010 and 2019, 35 no-hitters were pitched (not including five combined no-hitters involving multiple pitchers), and the closest anyone came in the 21st century is Max Scherzer, who in 2015 threw a one-hitter and no-hitter in consecutive starts, respectively losing out on perfect games in the seventh inning and on the 27th batter.[29][30][31]

Most career no-hitters – 7[edit]

Set by Nolan Ryan, 1966–1993. Sandy Koufax is second with four.[3] Larry Corcoran, Cy Young, Bob Feller, and Justin Verlander have all thrown three. Only Verlander is active.

In all, 26 pitchers have thrown two, including active player Max Scherzer. An additional 30 active pitchers have played a part in one, including 20 who have thrown an individual no-hitter.[30] Between 2000 and 2009, 20 no-hitters in all were thrown—19 of them solo no-hitters and one a combined no-hitter (in which more than one pitcher contributed). The following decade (2010–2019) saw the number of no-hitters double from the 2000s, with 40 (36 solo, 4 combined).[30]

Most career strikeouts – 5,714[edit]

Set by Nolan Ryan, 1966–1993.[33] Highlights include: six 300-strikeout seasons, fifteen 200-strikeout seasons, and leading the league in strikeouts 11 times.[34] To accomplish this record, Ryan played the most seasons (27) in MLB history,[32] as well as being both second in career innings pitched in the live-ball era, and fourth among pitchers who have completed their careers in strikeouts per nine innings.

The next closest player is Randy Johnson, who has 839 fewer strikeouts at 4,875.[35] Johnson also had four consecutive 300-strikeout seasons at the turn of the 21st century (1999–2002);[3] the only pitchers with a 300-strikeout season after 2002 are Clayton Kershaw, who had 301 in 2015; Chris Sale, with 308 in 2017; Max Scherzer, with 300 in 2018; and Gerrit Cole and Justin Verlander, respectively with 326 and 300 in 2019.[36] For a player to approach this record, he would have to average 225 strikeouts over 25 seasons just to get to 5,625. Averaging 250 strikeouts over 23 seasons would enable him to surpass the record with 5,750. Between 2010 and 2019 the Major League leader in strikeouts finished each year with an average of 279, and even that average is skewed with the aforementioned large strikeout seasons late in the decade. No pitcher exceeded 280 strikeouts between 2005 and 2014. Since then, only eight 280-strikeout seasons have been recorded—the five aforementioned 300-strikeout performances, plus Scherzer's 284 in 2016, Verlander's 290 in 2018, and Spencer Strider's 281 in 2023.[36] The closest active player is Scherzer with 3,367, with Verlander closely following with 3,342.[37]

Most career bases on balls – 2,795[edit]

Set by Nolan Ryan, 1966–1993. Ryan has more than 50 percent more bases on balls than the next highest (Steve Carlton with 1833).[33] The active pitcher with the most walks, Justin Verlander, finished the 2023 season with 925.[38]

Most innings pitched in a season – 680[edit]

Set by Will White in the same 1879 season in which he set the record of 75 complete games noted above (at this time the distance from mound to plate was 45 feet). The record pitching from the distance used since 1893 (60 feet 6 inches) is 482 innings that first year by Amos Rusie, which had been exceeded 85 times by pitchers working from 45 or (starting in 1881) 50 feet, including by Rusie himself the three previous consecutive seasons, but has never been approached since (Ed Walsh in 1908 was the last to pitch 400 innings in a season). The most innings pitched in a live-ball season (since 1920) was Wilbur Wood's 3762⁄3 innings in 1972.[39]

No pitcher has even thrown half of White's record total for innings in a season since Phil Niekro in 1979, with 342. The last 300-inning season to date was by Steve Carlton the following year, with 304. The highest single-season innings count in the 21st century was Roy Halladay's 266 in 2003, and the five lowest innings totals for an MLB leader in the sport's history (apart from three shortened seasons—1981 and 1994 due to strikes, and 2020 due to COVID-19) have all occurred since 2016—Chris Sale with 2141⁄3 in 2017, Logan Webb with 216 in 2023, Max Scherzer with 2202⁄3 in 2018, Justin Verlander with 223 in 2019, and Zack Wheeler with 2131⁄3 in 2021.[39]

Most career wild pitches thrown – 343[edit]

Set by Tony Mullane, who pitched from 1881 to 1894. Mullane pitched through a staggering 4531.1 innings (24th all-time) throwing a total of 343 wild pitches and averaged an errant pitch in 7.56% of those innings. Nolan Ryan is second on the list of most wild pitches with 277. The active leaders in wild pitches are Zack Greinke and Clayton Kershaw, each with 101, less than one-third of Mullane's total.[40] Modern pitchers throw wild pitches less frequently and pitch fewer innings.

Most innings pitched in a single game – 26[edit]

Set by Leon Cadore and Joe Oeschger, respectively of the Brooklyn Dodgers and Boston Braves, who were the only pitchers in a 26-inning marathon on May 1, 1920 that ended in a 1–1 tie due to darkness. Many commentators have cited this record as unbreakable, noting that modern teams generally use more than one pitcher in a regulation game, much less one that goes into extra innings.[41][42][43][44]

Batting[edit]

Most career hits – 4,256[edit]

Set by Pete Rose, 1963–86.[45] No active major league player is at this time considered to be close to breaking Rose's mark. Following the retirement of Albert Pujols (3,384) at the end of the 2022 season and Miguel Cabrera at the end of the 2023 season, no active player has even 3,000 hits, with the de facto retired Robinson Canó leading active players with 2,639 hits, followed by the 40-year-old Joey Votto, with 2,135 hits. The youngest player with at least 2,000 career hits is José Altuve, with 2,047 hits at the age of 33. He would have to average more than 200 hits over the next nine seasons to break the record.[46] To get within 6 hits of tying Rose, a player would have to collect 250 hits for 17 straight seasons,[47] or more than 200 hits over the course of 21 seasons. In the past 81 years, only Ichiro Suzuki, whose first season in Major League Baseball was his tenth in the top professional ranks, following nine years in his native Japan, has topped 250 hits in a season (with 262 hits in 2004).[47] Ichiro ended his playing career with 3,089 MLB hits[46] and 1,278 hits in the Japanese major leagues[48] (averaging just 106 games and 142 hits a year in much shorter Japanese seasons) for a combined, unofficial total of 4,367, 111 more than Rose's record; however, Ichiro's hits from Japan's major leagues are not counted toward his MLB total. At the end of the 2023 season, Cabrera retired with 3,174 hits after 21 seasons.[49] No player younger than Cabrera was within 500 hits of his career total at the end of the 2023 season, and among players no older than 30 at that time, only Francisco Lindor had even 1,300 career hits (1,323).[46]

Most career plate appearances – 15,890[edit]

Also set by Rose. MLB.com writer Matt Kelly noted in a 2023 story on records he saw as unbreakable that it was difficult to "imagine any player not only equaling Rose's 24 big league seasons, but also maintaining the excellence required to average 662 plate appearances per season as the Hit King did." Kelly added that Pujols had just ended his 22-season MLB career more than 2,800 plate appearances behind Rose.[50]

Most career total bases – 6,856[edit]

Set by Hank Aaron, 1954–1976. His total is more than 600 greater than second-place Pujols (6,211), and the active leader, the 40-year-old Votto, had only 3,706 at the end of the 2023 season.[50] Entering the 2024 season, the leader among players no older than 30 is Francisco Lindor with 2,283, less than one-third of Aaron's total.[51]

Most hits in a season – 262[edit]

Set by Ichiro Suzuki in 2004, breaking a record that had been set in 1920 by George Sisler (257).[52] Writing in 2019 for ESPN, Sam Miller argued that this relatively young record is nonetheless unlikely to be broken. He noted that the only active player who had collected more than 225 hits in any season was Ichiro himself,[26] who had done so three times.[52] The next-highest total since 2000 was 240 hits by Darin Erstad in 2000.

Miller wrote that in today's game, "few elite hitters are as walk-averse as Ichiro was permitted to be", which he argued would keep other players from approaching the record. The MLB leader in at-bats in 2018 was Trea Turner with 664; a player with that number of at-bats would have to hit .396 to reach 263 hits—a batting average that Miller had argued in 2018 was unapproachable in the modern game.[53] He added,[26]

The outer limit for at-bats – say, a leadoff hitter for a high-scoring team who plays every game and has a 10th-percentile walk rate – is perhaps 725, nine higher than the all-time record. And even the 725-AB guy would need to hit .363, a mark not met by any hitter in this decade.

The aforementioned Matt Kelly added that Ichiro had 704 at-bats in the 2004 season, making him one of only four players with more than 700 at-bats in a season. Kelly added, "So to break this record, you'd have to hit .373 and log more than 700 ABs. Good luck."[50]

Most consecutive seasons with 200 hits – 10[edit]

Set by Ichiro Suzuki, from 2001 to 2010.[54][55][56] The closest player is Willie Keeler, who had eight consecutive seasons with 200 hits almost a century earlier, in the dead-ball era.[57] No players at all had 200 hits in 2013, 2018, 2020, 2021 and 2022 seasons, in 2023 only three players had 200 hits, and in 2019, only Whit Merrifield and Rafael Devers did so.[58]

Most career doubles – 792[edit]

Set by Tris Speaker, 1907–1928.[59] Highlights include: five 50-double seasons, ten 40-double seasons, and leading the league in doubles eight times.[60] The next closest player is Pete Rose, who has 46 fewer doubles at 746. Among hitters whose entire careers were in the live-ball era, the leader in career doubles is the aforementioned Rose.

For a player to threaten Speaker's record, he would have to average 39 doubles over 20 seasons just to get to 780, or 40 doubles in 20 seasons to break the record. Between 2010 and 2019 the Major League leader in doubles finished each year with an average of 51, with José Ramírez setting a decade-high of 56 doubles during the 2016 season.[61] However, players tend to hit less doubles as they age, thus making difficult for most players to keep hitting doubles consistently for long enough to challenge the record. Following the retirement of Albert Pujols who ended his career in 2022 with 686 (a record for a right-handed hitter),[62] and Miguel Cabrera, no active player has even 500 doubles, with the closest being Freddie Freeman at 473 at the end of the 2023 season. No player younger than 30 has even 300 doubles at the end of the 2023 season, although five players with that total turned 31 during or shortly after that season (Mookie Betts, 347; Xander Bogaerts, 339; Manny Machado, 333; Bryce Harper, 327; and José Ramírez, 325). The player with the most career doubles no older than 30 is Francisco Lindor, who has 265 and turned 30 shortly after the end of the 2023 season. In order to break the record, Freeman would need to average 40 doubles over 8 seasons; the aforementioned players in their early thirties with 300-plus doubles would need to average at least 44 doubles over 10 seasons; and Lindor would need to average 44 doubles over 12 seasons.

Most career triples – 309[edit]

Set by Sam Crawford, 1899–1916. Highlights include: five 20-triple seasons and sixteen 10-triple seasons.[63] The next closest player is Ty Cobb, who has 14 fewer triples at 295. Because of changes in playing styles and ballparks that began around 1920 and have continued into the present from the dead-ball era to the live-ball era, the number of triples hit has declined noticeably since then. Among hitters whose entire careers were in the live-ball era, the leader in career triples is Stan Musial, with 177.

For a player to threaten Crawford's record, he would have to average 15 triples over 20 seasons just to get to 300. Between 2010 and 2019 the Major League leader in triples finished each year with an average of 13, and no player in that decade had more than 16 in a season. Bobby Witt Jr. and Corbin Carroll, respectively with 11 and 10 triples in 2023, are the only players in the 2020s to hit even 10 triples in a season.[64] At the end of the 2023 season, the closest active player is Charlie Blackmon with 63; the closest active player 30 or under is Trea Turner with 41.[65]

Most triples in a season – 36[edit]

Set by Chief Wilson in 1912.[66][67] Only two other players have ever had 30 triples in a season (Dave Orr with 31 in 1886 and Heinie Reitz with 31 in 1894),[67] while the closest anyone has come in the century since Wilson set the record is 26, shared by Sam Crawford (1914) and Kiki Cuyler (1925).[67] Only six hitters have had 20 triples in the last 50 years: George Brett (20 in 1979), Willie Wilson (21 in 1985), Lance Johnson (21 in 1996), Cristian Guzmán (20 in 2000), Curtis Granderson (23 in 2007) and Jimmy Rollins (20 in 2007).

Sam Miller also added that Chief Wilson was playing his home games in Forbes Field, which in 1912 had a 460-foot center-field distance, noticeably longer than any current MLB park. In his record-setting season, Wilson hit 24 triples at home, a total that has not been surpassed in an entire season since 1925. Additionally, Wilson himself never hit more than 14 triples in any other season. On top of this, no minor-league player has ever had more than 31 triples in a season, despite that level of the game having less capable defenders, many quirky ballparks (more so in past decades than today), and in some historical cases much longer seasons.[26]

Most walks drawn in a season – 232; most intentional walks drawn in a season – 120[edit]

Both records set by Barry Bonds in 2004. The aforementioned Matt Kelly noted that the only other player who had drawn even 170 walks in a season was Babe Ruth in 1923. As for intentional walks, Bonds himself is the only player to have drawn even half of his 2004 total in any other season (68 in 2002, 61 in 2003); the next-highest player is Willie McCovey with 45 in 1969.[50][68]

Most home runs in a game – 4[edit]

In all, 18 players have hit four home runs in a game. A five-homer game would require not only that a player get five plate appearances, but that he receive hittable pitches in each appearance. Only three players, having hit four in one game, have ever made a plate appearance that could have resulted in a fifth: Lou Gehrig in 1932, Joe Adcock in 1954 and Mike Cameron in 2002. In Gehrig's last at-bat, he hit a deep fly to center; Adcock hit a double off the top of the wall (his 18 total bases was a record until Shawn Green broke it in 2002). Breaking this record would also set the single-game record for most total bases, with 20. Relatedly, no player has homered in five consecutive at-bats over multiple games. However, home runs are being hit at ever-increasing rates, reflecting batters' increased focus on "launch angles", a dramatically reduced stigma for strikeouts, and, some allege, that MLB has "juiced" the ball.[69] These factors increase the prospect of a five-homer game, particularly over extra innings.

Most grand slams in a single inning – 2[edit]

Set by Fernando Tatís in 1999.[70] Only twelve other players have ever hit two grand slams in a single game.[71] However, breaking the record would require a player to hit three grand slams in a single inning. Breaking this record would also tie the major league record for RBI in a single game (12). Over 50 players have hit two home runs in a single inning,[72] but no MLB player has so much as hit three home runs in one inning. One minor league player, Gene Rye, hit three home runs in a single inning.[73]

Highest career batting average – .366[edit]

Set by Ty Cobb in 1928 after beginning his career in 1905.[74] Highlights of this record include three .400 seasons; nine .380 seasons; and leading the league 11 times in batting average.[75] Cobb managed to hit .323 in his final season at age 41.[76] The next-closest player is Rogers Hornsby who had a batting average of .358. The careers of both Cobb and Hornsby straddled the dead-ball and live-ball eras; most of Cobb's career was in the dead-ball era, while most of Hornsby's was in the live-ball era. There are only three players with a career average over .350, and the highest batting average among those who played their entire careers in the live-ball era is Ted Williams' .344. Since 1928, there have been only 46 seasons in which a hitter reached .366 and only Tony Gwynn attained that mark at least four times, finishing with a career .338 batting average.[77] At the end of the 2023 season, after the retirement of Miguel Cabrera, José Altuve leads active players in career batting average with .307, 6 points above Freddie Freeman at .301.[78]

Highest single-season batting average – .440[edit]

Set by Hugh Duffy in 1894, the highest single-season average in National League, and MLB history. Nap Lajoie’s .426 in 1901 is the highest in American League history. In the live-ball era, Rogers Hornsby hit .424 in 1924, a feat unmatched since then. George Sisler's .420 average in 1922 still stands as the highest American League average of the modern era. Ted Williams hit .406 in 1941, the last player in either league to top .400 for a season. Since then, only George Brett, who hit .390 in 1980, and Tony Gwynn, who hit .394 in a strike-shortened season in 1994, have even come close to reaching .400, and they were nowhere near any of the historical league or MLB highs.

In a 2018 ESPN story, Sam Miller argued that it was impossible to hit .400, or even seriously challenge the mark, in the modern game, noting that no hitter in the 21st century entered the second half of the season with an average above .380, and at that time, no batter since 2009 who qualified for his league's batting title had a .400 average at any point after May 25. Additionally, Miller argued that a player who might conceivably challenge .400 would have to combine a low strikeout rate, high home run rate, and high batting average on balls in play—a group of skills which largely do not complement one another.[53] In the 2023 season, Luis Arráez became the first player in recent times with an average above .400 after May 25, by going 2-for-4 in a 6-1 win against the Kansas City Royals on June 6,[79] but finished the season with an average of .354.[80]

Most RBI in a season – 191[edit]

Set by Hack Wilson, who batted in 191 runs in 1930. Only Lou Gehrig and Hank Greenberg, at 184 and 183 RBI respectively, ever came close, and there have been no real challenges to the record for over 75 years.

However, Sam Miller argued in ESPN in 2019 that a serious challenge to Wilson's record, though highly unlikely, was less implausible than challenges to many of the other records listed here. He noted that in 1930, Wilson came to bat with 524 runners on base, drove in 22.7% of them, and hit 56 homers. Neither the number of baserunners nor the RBI percentage is within the top 60 seasons for those statistics in MLB history, with some seasons in the top 60 of both categories having been recorded in the 21st century, and he added "we've all seen players hit 56 home runs, even this decade."[26] However, with today's batters pursuing one of baseball's so-called "three true outcomes" – a home run, walk, or strikeout – there is less likelihood of enough runners on base for such a season to produce anything like 191 RBI.[citation needed]

Most runs scored in a season – 198[edit]

Set by Billy Hamilton in 1894; modern-era (post-1900) record of 177 set by Babe Ruth in 1921. Matt Kelly, who analyzed only Ruth's record, noted that while Ruth had benefited from a New York Yankees lineup that collectively hit .300, he also hit 59 home runs, then an MLB record, and reached base 353 times, still the fifth-highest total in the modern era. Only one player in the modern era was within 10 runs of Ruth's record (Lou Gehrig with 167 in 1936), and the highest total since 1950 was Jeff Bagwell's 152 in 2000.[50][81]

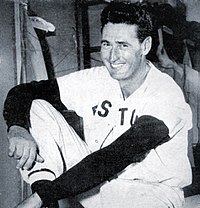

Highest career on-base percentage – .482[edit]

Set by Ted Williams from 1939 to 1960.[82] Williams, the last man to hit .400 in an MLB season (.406 in 1941), won six American League batting titles, two Triple Crowns, and two MVP awards. He ended his career with 521 home runs and a .344 career batting average. Williams achieved these numbers and honors despite missing nearly five full seasons to military service and injuries.[83] The next-closest player in career OBP is Babe Ruth at .474.[84]

Since Williams' retirement, only four players have posted an OBP above .482 in a season, with Barry Bonds and Mickey Mantle the only ones to do so more than once.[82][85] Bonds ended his career with an OBP of .444; the leader among active players is Juan Soto, at .421 after the 2023 season.[84]

Fewest strikeouts in a qualified season – 2[edit]

Set by Wee Willie Keeler in 1899. One of the greatest contact hitters of MLB history, he played a full season (633 PA, 570 AB) during which he struck out only twice.[86] Of course, he thereby also set another untouchable record: a single-season AB-per-SO of 285![87] The only possible challenger is the 1876 season of Mike McGeary, who struck out only once in 270 AB, but McGeary played in only 61 games and his single-season AB-per-SO of 270 is lower than Keeler's.[88] With the stipulation of +500AB, Keeler's record is untouchable.

Most regular season games played, season – 165[edit]

The record was set in 1962 by Los Angeles Dodgers shortstop Maury Wills,[89] who played in all of the team's 165 regular season games that year. Thanks to a best-of-three playoff between the Dodgers and San Francisco Giants, which ended the season tied for first place (back when league pennants were winner-take-all, with no annual end-of-season multi-tiered layers of playoffs, play-ins, and wild cards), both teams played 165 games. Because the play-off was to determine the regular season winner of the league championship, the games were counted as extensions of the regular season, and not the post-season, which at that time was composed solely of the World Series.

Both the individual and team single-season games played records were set at the beginning of a seven-year span that began with the 1962 National League expansion to 162 games and ended after the 1968 season, when the NL replaced its traditional best-of-three tiebreakers with one-game playoffs. The 1962 season was the only occasion during those years in which a tie-breaker was needed. Until the abolition of tie-breaker games prior to the 2022 season, the American League always used one-game playoffs.

Prior to the end of the 2021 season, there were a few occasions prior where three or more teams could have tied for postseason berths going into the last day of the season, which under the rules then in force would have resulted in one or more teams having to play at least two other teams in successive tie-breakers. However, a three-way tie involving postseason berths never occurred, meaning that other than in the aforementioned 1962 season no team ever played more than 163 regular season games.

As part of the provisions of the 2022 Basic Agreement, MLB expanded the playoffs and replaced one-game tie-breaker games with performance-based criteria to break future ties. Thus unless and until the regular season schedule is extended, which is considered extremely unlikely since all expansions to the season length have been to extend the postseason, no team will play more than 162 regular season games.

Historically, there have been two other ways for a player to accumulate more than 162 games played in a season. The first is if the player changes teams in a mid-season trade - a swap to a team that has played fewer games can result in a schedule for the traded player being greater than either individual teams'. Presently '70s-era speedster Frank Taveras[89] holds the records for both most regularly scheduled MLB games played in a season[citation needed] and most games played for two teams in the same season,[citation needed] both 164, done in 1979. However, even by this method Wills' individual record is statistically ever more unlikely to be broken because teams are increasingly inclined to rest even their best players as part of a new sabremetrics-based strategy known as "load management". On average, as of the early 2020's only about three players in all of baseball appear in even 162 regular season games of any given MLB season.

The other method in which a player can be credited with more than 162 games played is when games are called with the score tied after the game becomes official, i.e. after five or more innings are played. In recent decades, this was almost always due to adverse weather, although historically such games were also called due to darkness and/or curfews. Due to the tie score, such games did not count in the official standings and were replayed in their entirety. However, player statistics still counted, allowing for example Hideki Matsui to play 163 games for the New York Yankees in 2003. The rules were changed in 2007 to require such tie games to be suspended. The games are then completed at a later date (rather than replayed in full) if feasible and/or required to determine postseason qualification. This change makes such a scenario highly unlikely to be seen again.[90][91]

Most consecutive games played – 2,632[edit]

Set by Cal Ripken Jr., 1982–1998.[92] Lou Gehrig, whose record Ripken surpassed in 1995, had a consecutive games streak of 2,130 games, 502 fewer.[29][92][93] Third on the all-time list is Everett Scott, whose streak of 1,307 consecutive games is less than half of Ripken's total.[93] Only seven players have ever played more than 1,000 consecutive games.[93] For a player to approach the milestone, he would have to play all 162 games in a season for 16 years just to get to 2,592 games.

As stated by LIFE, "no one else has ever come close, and no one ever will."[92] On average, over the preceding ten seasons from 2009 to 2018 only three players have played all 162 regularly-scheduled games in a particular season.

Longest hitting streak – 56 games[edit]

With pitching the way it is—specialty guys, closer and setup guys—you're not going to have a chance to get four at-bats against one guy. On one night, you might face four different guys. I'm still amazed DiMaggio got to 56. I'm amazed now when somebody gets to 30.

—Robin Ventura, who set the NCAA Division I record of hitting in 58 consecutive games[94]

Set by Joe DiMaggio, 1941.[2] Highlights of his hitting streak include a .408 batting average and 91 hits.[95] The next closest player is Willie Keeler, with 45 over two seasons in 1896–97.[96] There have been only six 40-game hitting streaks, and only Pete Rose's 44 in 1978 since DiMaggio's.[96][97] Since 1900, no player other than DiMaggio has ever hit safely in even 55 of 56 games, and no active players (as of 2019) have their two longest career hit streaks even add up to 56 games.[26][98]

On July 17, 1941, pitchers Al Smith and Jim Bagby of the Cleveland Indians held DiMaggio hitless. Two hard hit shots came close, but great defensive stops by third baseman Ken Keltner ended the streak.[99] "Joltin' Joe" actually hit in 57 straight MLB games – singling in the 1941 All-Star game held mid-streak[100] – and 73 out of 74 regular season games, starting a 17-game streak the day after his 56-game one ended.[101] He also holds the second longest streak in minor league baseball history, 61 games, set in 1933.[100]

The improbability of DiMaggio's hitting streak ever being broken has been attributed to increased bullpen use, including specialist relievers.[93]

Most career home runs by a pitcher – 37[edit]

Set by Wes Ferrell, who hit 37 home runs while playing for the Indians, Red Sox, Senators and Yankees during the late 1920s and most of the 1930s (Ferrell hit one more home run while with the Braves in 1941, bringing his total to 38 – 37 as a pitcher and one as a pinch-hitter – the most for any MLB pitcher). With a total of 326 hits in 1,176 at-bats in his 17-year career, Ferrell hit .280 and had 208 RBIs,[102] and is considered one of baseball's best-hitting pitchers.

Other pitchers with more than thirty career home runs include Bob Lemon, who hit 35 HR as a pitcher and two more as a pinch hitter during his 18-year career, all spent with the Indians; Warren Spahn, who hit 35 while playing for the Braves and is the all-time National League leader; Red Ruffing, who had 34 home runs as a pitcher and two more as pinch-hitter over 22 seasons with the Red Sox, Yankees and White Sox; and Earl Wilson, who hit 35 home runs in an 11-year career – 33 as a pitcher and two as a pinch-hitter – all but one of them while with the Red Sox and Tigers, and the last as a Padre.[103]

By the latter half of the twentieth century, "good-hitting pitchers" had clearly become the exception rather than the rule. The American League's adoption of the designated hitter rule in 1973 led to the widespread substitution of the DH in the pitcher's slot in the batting order in regular season, All-Star and postseason games played in AL parks. Since then, Ferrell's record has been widely considered an unbreakable AL record. Even after AL pitchers resumed batting more frequently in 1997 with the introduction of interleague play, since then no American League pitcher has received enough at-bats to seriously challenge any of the above home run statistics (or any other game, seasonal or career hitting marks set by AL pitchers historically).

While pitchers would continue to bat in National League parks for almost a half century after the AL introduced the DH, the aforementioned changes to in-game team management and season structure during that period made a serious challenge to Farrell's record increasingly unlikely - specifically, the introduction of interleague play conversely meant that NL pitchers received fewer at-bats since their teams used the DH when playing in AL parks and the aforementioned drastic reduction in complete games (and corresponding increasing use of relief pitchers) in turn increased the opportunity to use pinch hitters in the pitcher's spot in the batting order. All these factors combined to substantially reduce the number of at-bats per game any individual pitcher could have expected to receive even in NL parks. The career MLB leader for home runs by a pitcher since the introduction of the DH in the AL is Carlos Zambrano, who played his entire career in the interleague era and recorded 24 homers in NL parks.

During the pandemic-shortened 2020 season, the DH was used throughout MLB, although it was dropped again in NL parks for the 2021 season. As part of the new Basic Agreement prior to the 2022 season, MLB owners and players agreed to the permanent inclusion of the DH in all MLB parks. At the time of the permanent implementation of a universal DH, the leader among then-active pitchers was Madison Bumgarner with 19 home runs.

However, a notable caveat to the unbreakability of this record concerns Japanese player Shohei Ohtani, who has excelled as both a starting pitcher and a designated hitter since signing with the Los Angeles Angels in 2018. Ohtani's signing led to speculation that Ferrell's record would quickly be broken, however, Ohtani did not hit and pitch in the same game until the 2021 season[104] and MLB quickly clarified that his home runs hit while not pitching would not be scored as being hit "by a pitcher." Notably, Ohtani hit 46 home runs in the 2021 season alone. This total includes the first three of his career (all in AL parks) that Ohtani hit while pitching. The implementation of the universal DH essentially coincided with additional rule change dubbed the "Ohtani rule" that allows batting pitchers to remain in the game as a DH after being relieved from the mound. The "Ohtani rule" largely eliminates the disincentive against a good-hitting pitcher batting in the same game since it means relievers do not have to bat for themselves (or be replaced by pinch hitters) in games where the starting pitcher appears at the plate. Ohtani, who was 27 as of the start of the 2022 season, needed 38 home runs while pitching to officially break Ferrell's record. As per the terms of the "Ohtani rule," hitting statistics recorded by a batting pitcher after any defensive half-inning completed by him will be scored as being hit by a pitcher whether or not he returns to the mound to start the next defensive half-inning, but hitting statistics compiled after a reliever appears on the mound will not.

Most career sacrifice bunts – 512[edit]

Set by Eddie Collins, who successfully laid down 512 sacrifice bunts over his 25-year career with the Philadelphia Athletics.[105] Second behind him is Jake Daubert with 392. Since the turn of the 20th century, sacrifice bunts have continually fallen further out of favor: Moneyball by Michael Lewis, the famous sabermetrician's guide, went as far as to label the bunt as "evil". Modern baseball teams value minimizing outs rather than moving a base-runner over a single base position.

Over the decades prior to the 2021-22 lockout, bunting was most often attempted by players with limited hitting abilities – usually pitchers in National League parks who when required to bat often attempted to advance baserunners as opposed to trying to reach base (and run the basepaths). However, there was no point in the history of the game where pitchers played anywhere close to enough innings to have a realistic opportunity to challenge Collins' record. At the end of the 2021 season the active leader in career sacrifice bunts, pitcher Clayton Kershaw, had 108 — which placed him in a tie for 334th on the all-time list. With the NL adopting the DH in 2022, Kershaw (who entered that season as a free agent) is unlikely to ever bat again. Among position players, the active leader is Elvis Andrus with 103 (tied for 383rd).[106]

Most stolen bases in a season – 130[edit]

Set by Rickey Henderson with 130 in 1982, a season in which he was caught stealing 42 times. No player has even attempted 130 steals in a season since Vince Coleman in 1985, and the stolen base has been a steadily declining part of the game since then.[50] No player in the 2018 season even attempted one-third of Henderson's total attempts in 1982, and in the 2017 season, no American League player attempted more than Henderson's 1982 caught-stealing total of 42. Additionally, while Billy Hamilton set a minor-league record with 155 steals in 2012, he has never stolen more than 60 in any season of his MLB career.[26]

Most career stolen bases – 1,406[edit]

Set by Rickey Henderson, 1979–2003.[29][107] Highlights include: three 100-stolen-base seasons,[47] thirteen 50-stolen-base seasons, and leading the league in stolen bases 12 times.[108] The next closest player is Lou Brock, who has 468 fewer stolen bases at 938. According to LIFE, the stolen base record is probably unbreakable, as it is hard to imagine a player today who would "even attempt so many steals."[107] For a player to approach Henderson's milestone, he would have to average 70 stolen bases over 20 seasons just to get to 1,400.[47] Between 2000 and 2009, the Major League leader in stolen bases finished each year with an average of 64, and that number dropped to 57 in the 2010s—a decade in which no player stole 70 bases in a season. Ronald Acuña Jr.'s 73 stolen bases in 2023 are the most in a season since 2007.[109] The closest active player is Elvis Andrus with 347 stolen bases, less than 25% of Henderson's total.[47][110]

Most steals of home in a career – 54[edit]

Ty Cobb holds the record of 54 steals of home in his career. Since there is rarely a single steal of home in any season now, this record stands little chance of ever being approached, let alone surpassed.[111]

Fielding[edit]

Most outfield assists in a season – 50[edit]

Set by Orator Shafer in 1879. Since 1900, no other player has had more than Chuck Klein's 44 in 1930, and nobody has had more than Boston Braves right-fielder Gene Moore's 32 since 1936.[113]

Most outfield assists, career – 449[edit]

Set by Hall of Famer Tris Speaker (1907–28).[114] Speaker is regarded as the greatest fielding centerfielder ever, known for playing exceptionally shallow and going back on balls rather than coming in. Playing shallow in his era both erased a lot of hits and led to high assist totals: 14 seasons with more than 20 and four with more than 35. The closest any player has since come is 266 by Roberto Clemente (1955–1973).[114]

Most errors, career – 1,096[edit]

Herman Long holds the record with 1,096 career errors; he played from 1889 to 1904. Bill Dahlen, Deacon White and Germany Smith are the only other players to commit at least 1,000 errors during their MLB careers. All of these players played at least one season before 1900. The 20th-century record is held by Rabbit Maranville, with 711 errors. Among active players, Elvis Andrus, who has played in MLB since 2009, leads with 231 career errors (nearly 60 more than any other active player) after the 2023 season.[115]

The much greater frequency of errors in the game's early decades can be attributed at least as much to a significantly lower standard of equipment as to an inferior level of skill. In particular, gloves did not gain widespread acceptance until the end of the 19th century and remained primitive by modern standards for several decades thereafter. Also, baseballs themselves were far more expensive relative to inflation (and especially relative to club finances) compared to today. Furthermore, the rules strictly enforced today to prevent their adulteration did not exist in that era. Balls were only replaced when absolutely necessary, and as a result were much more difficult to handle and throw effectively.

Other[edit]

Most All-Star Games played – 25; most seasons on an All-Star roster – 21[edit]

Both records set by Hank Aaron, 1954–1976. Aaron was an All-Star in all but two of the 23 seasons he played in the major leagues (his debut year in 1954 and last season in 1976). His record total was aided by MLB's decision to hold two All-Star Games annually from 1959 to 1962;[116] Aaron played in all eight All-Star Games during that period. His 21 seasons on an All-Star roster are also the most in MLB history. The only players whose careers began after 1976 to play in 25 MLB seasons were Rickey Henderson, who appeared in 10 All-Star Games,[116] and Jamie Moyer, who appeared in one.[117] The active player with the most All-Star Game selections is Mike Trout, who has been on 11 All-Star Game rosters after 13 seasons.[118]

Aaron's record for most seasons on an All-Star roster is more approachable than his record for All-Star Game appearances. In addition to the aforementioned Henderson and Moyer, 26 players whose careers began after 1976 have played in at least 21 MLB seasons.[119] However, the most All-Star seasons among these players is the 14 of Barry Bonds and Iván Rodríguez, who respectively played in 22 and 21 seasons. The most All-Star seasons among players whose careers began after 1976 is 19 by Cal Ripken Jr.[118]

Most wins, losses and games managed – 3,731, 3,948, and 7,755[edit]

Set by Connie Mack, who retired in 1950.[120] Mack owned the Philadelphia Athletics, and managed them for 50 years, until the age of 87.[120] Shortly after his retirement Major League Baseball forbade owners from managing their teams.[citation needed] Mack also was the manager in 76 ties as he managed in an era where games could be called due to darkness and/or local curfews.[121] As ties are now extremely rare as a result of rules changes, modern stadium lights, and much more lenient curfews (where they are in force at all) in MLB cities, this record is likely unbreakable given the current rules.[91] Also, during baseball's early decades, owners who did not manage their own teams often sought to have a veteran player fill the role in order to reduce payroll costs. Such arrangements led to the "player-manager" position becoming relatively common in baseball and afforded greater opportunity to start a managerial career at a relatively young age.

Mack is also the oldest manager in MLB history – the only other person to manage in the majors after his eightieth birthday is Jack McKeon who retired shortly before his 81st birthday. Among managers active in 2023, the closest manager to Mack in games managed, wins, and losses is the 74-year-old Dusty Baker (3,884 games, 2,093 wins, 1,790 losses entering the 2023 season). The manager second to Mack in all three categories, Tony La Russa (5,393 games, 2,884 wins, 2,499 losses), returned to managing in 2021 at age 76 after a 10-year absence from that role, but took a medical leave during the 2022 season and later announced he would not return in 2023. Given that Baker ended the 2022 season with 10 fewer seasons as a manager than La Russa, he would have to manage into his eighties before challenging La Russa's totals, much less Mack's.[122] The next-closest active manager in games, wins, and losses is Terry Francona (age 64), who entered the 2023 season with 3,460 games managed (18th), 1,874 wins (17th), and 1,586 losses (17th).[122] Both Francona and Baker announced their retirement from managing after the 2023 season.

Under the current 162-game schedule, a person would have to manage for 48 seasons to challenge Mack's records. Thus, for example, a person would have to manage continuously starting in the year he turned 32 to have a chance to reach 7,756 games before turning 80, and even then only if no seasons were significantly shortened and/or canceled due to labor disputes, public health emergencies and/or other extenuating circumstances. With the de facto elimination of the player-manager position (the last player-manager in MLB was the aforementioned Pete Rose, who incidentally was in that role for the Cincinnati Reds when he broke Ty Cobb's all-time hit record) and the increasing tendency of players who display the leadership qualities that warrant eventual consideration for employment as field managers also having longer playing careers, it is now uncommon for anyone to earn their first MLB managerial position prior to turning 40.

The youngest two managers in MLB in the 21st century are Eric Wedge and A. J. Hinch, who were both 35 when they first managed in the majors. Both were players who had their careers cut short by injuries but had also displayed strong leadership qualities. Wedge has not managed in the majors since 2013, while Hinch has had two stints away from managing (the most recent being a one-year suspension due to his role in the Houston Astros sign stealing scandal, although it should be noted this suspension was served during the pandemic-shortened 2020 season which effectively shortened all active careers by at least 102 games). As of 2023, any current or recently-active MLB manager would have to break Mack's record as the oldest manager before challenging any of his other records.

Most road losses in a season – 101[edit]

The 1899 Cleveland Spiders (20–134) hold the MLB record for the most road losses in a single season, with 101. They were so bad – 20 wins below the 1962 New York Mets – they likely set an unbreakable record for fewest wins in a full season at the same time. In terms of absolute numbers the Spiders' record for fewest wins has been nominally "broken" by the 2020 Pittsburgh Pirates, who won exactly one fewer game than the 1899 Spiders by finishing 19–41 in the pandemic-shortened sixty-game season.

What is unusual, however, about the Spiders' road loss record compared to others on this list is that while most others are theoretically possible (but impractical) to break, it cannot be broken even if a team achieved a completely winless season on the road: in today's sport, the 162-game season is equally divided between 81 home and road games, 21 fewer than needed to set a new mark.[123]

While rainouts and other cancellations can reduce the number of games a team plays in a season, the only way a team could accumulate the 21 extra road games needed to break the record is if a team’s stadium suffers damage that makes games unplayable there that forces a team to move a large chunk of home games to the visiting team’s stadium (examples including the 1991 Expos and 1994 Mariners) if the number of games affected is 21 or more (with 32 or more games affected being needed to break the record for number of away games). The only situation in which regular season games were ever added to the schedule is in the case of the now-abolished one-game playoff; the odds of a team losing all of its road games but still having a record strong enough to qualify for such a game were infinitesimally small. While in the uncommon circumstance that a game must be moved to the opposing venue, MLB policy now maintains the legal fiction that the designated home team does not change, regardless of venue, which ensures the designated home team does not lose rules advantages, the game is still changed to counting as an away game for the team. This was not the case in 1899, when 35 of the Spiders' home games were changed to true road games.

Four other factors contribute to the unique nature of the Spiders' record:

- In the nineteenth century, owners were allowed to own more than one team. In 1898 the Spiders finished a respectable fifth in the NL, but dead last out of twelve teams in attendance at only 70,496 for the entire season. In contrast the St. Louis Browns (now Cardinals) were by far the worst team on the field but still drew respectable crowds by the standards of the time, especially considering the team's poor performance. Observing that the Browns had drawn 151,700 (more than double Cleveland's total), Spiders owners Frank and Stanley Robison decided it would be more profitable to have a good team in St. Louis. They purchased the Browns, renamed them the Perfectos and proceeded to brazenly trade the Spiders' best players from 1898 – including future Hall of Fame pitchers Cy Young, Jesse Burkett and Bobby Wallace – to the Perfectos in exchange for St. Louis' least desirable players, with their manager, Patsy Tebeau. From 1900, MLB rules have prohibited a single owner owning more than one team to avoid any repeat of this, or any similar, arrangements.

- Baseball teams in 1899 had gate receipts as their main source for revenue. Resigning themselves to the reality that fans in Cleveland were not going to pay to watch a decimated roster, the Spiders/Perfectos ownership transferred all of the Spiders' home games against the Perfectos to St. Louis. As the season wore on, the already-puny crowds in Cleveland shrank in response to mounting losses to a fraction of even their NL-worst 1898 numbers. In all 42 games played in 1899 in Cleveland the Spiders drew only 6,088 fans – an average of 145 per game. In response to the mounting fiasco, the other ten NL teams requested the Spiders transfer home games to their parks as well since their cut of the gate receipts would leave them unable to recoup the expenses of the journey. Since the Spiders' cut of the gate receipts for road games was far more lucrative than their gate receipts for home games, the Spiders' owners were not inclined to object to such requests. Thus, the Spiders only played eight home games after July 1, giving them the opportunity for 101 road losses (against 11 wins).

- Today, MLB revenue streams are far more numerous, while in the case of media rights are often both contractually dependent on teams playing their entire schedule, and are not affected by attendance, while travel expenses make up a much smaller portion of a team's budget. MLB rules also state any team that refuses to travel to their opponent's stadium for a scheduled game would immediately forfeit the game.

- In the nineteenth century, NL scouting practices were rudimentary by modern standards and the modern minor league farm system did not exist in its present form. Technology was certainly one limiting factor- at the end of the 19th century, the railroad and telegraph were the most advanced forms of transportation and communication respectively in common everyday use. NL club management thus often had little knowledge of prospects playing in other leagues besides perhaps those playing relatively nearby. Notwithstanding technological limitations however, scouting and recruiting efforts were essentially limited to the United States, with the enforcement of the color barrier limiting the NL's potential talent pool even further. While NL clubs did cultivate relationships with teams in other leagues, procuring players from them often involved contentious negotiations with teams in autonomous leagues that (at best) grudgingly accepted NL pre-eminence (indeed, it was resentment of the NL's attempts to dominate combined with the contraction of the Spiders and three other teams that directly led to the formation of the American League). While NL owners sometimes tried to overcome this by acquiring financial interests in "minor league" clubs, even under those arrangements they could become under certain circumstances be willing to forego whatever rights they had to move such a team's best players to the NL - this was especially common if the "minor league" team was in its own pennant race and/or doing reasonably well at the gate. In any case, there is no evidence that the owners of the Spiders, after deciding to strip its roster of the best players, made any effort to replace them (say, by trying to purchase the contracts of potentially better players in other leagues). Instead, they compelled the Cleveland team to play the 1899 season with the roster they had. The end result was a team worse than the likely relative result of a 21st century MLB organization going as far as trading away its entire major league roster (and/or letting the whole roster leave via free agency) then signing only replacement-level players willing to play for the MLB minimum salary.

- The popular sabermetric statistic Wins Above Replacement (WAR) is based on the premise that an MLB team consisting of only replacement-level players would still be expected to win 40–50 games in a season, depending on factors such as the strength of its division. This is mostly because over the course of the twentieth century, the talent pool available to Major League Baseball became several orders of magnitude deeper than it was in the nineteenth century for a number of reasons including:

- Baseball becoming popular in much of the world outside the United States, which combined with overall population growth has resulted in many more young players taking up the game;

- Growing economic prosperity in baseball-playing nations allowing more young players to pursue the game seriously enough to eventually attract the attention of scouts;

- The elimination of the color barrier in the middle of the twentieth century due to the efforts of Branch Rickey and others, followed by the somewhat related development of MLB increasingly signing players from Asia, Latin America and elsewhere, thus giving MLB access to vast additional pools of talent that it deliberately avoided in 1899;

- The development of the modern minor league farm system (also championed by Rickey) and later innovations such as the Major League Baseball draft eventually resulted in talent below the major league level being more evenly distributed between all MLB organizations.

- Innumerable technological advancements, including not only in more general fields such as transportation and communication but also more specific developments tailored to the game such as highly sophisticated and customized computer software to help baseball teams track prospects around the world.

- Finally, in the latter part of the 20th century the Office of the Commissioner of Baseball centralized much of MLB scouting in what is now known as the Major League Baseball Scouting Bureau, in an effort to further improve parity across the major leagues.

- The popular sabermetric statistic Wins Above Replacement (WAR) is based on the premise that an MLB team consisting of only replacement-level players would still be expected to win 40–50 games in a season, depending on factors such as the strength of its division. This is mostly because over the course of the twentieth century, the talent pool available to Major League Baseball became several orders of magnitude deeper than it was in the nineteenth century for a number of reasons including:

- In spite of the aforementioned circumstances, the 1899 Spiders still managed to play their entire 154-game schedule – an unusual occurrence in an era when cancellations and ties were much more frequent, and the affected games were often not made up.

The 1899 Spiders also hold the records for the most losses in a single MLB season (with 134) and lowest winning percentage (.130). While these are technically possible to break, even under a 162-game schedule, only two teams have come within 15 losses of the record, these being the expansion 1962 New York Mets (40–120, .250 winning percentage) and the 2003 Detroit Tigers (43–119, .265 winning percentage).

Since 1899, only five teams have recorded a winning percentage under .260 (i.e. less than double that of the 1899 Spiders), and the 1962 Mets are the only team to do so under a 162-game schedule. Excluding the possibility of canceled games not being made up, a team would need to lose 141 games over a 162-game season to record a .130 winning percentage (this yields a .129 winning percentage if the traditional rounding to three decimal places is ignored).

Lowest paying attendance – 6[edit]

This was set by the Worcester Worcesters, in a September 28, 1882 game against the Troy Trojans at the Worcester Agricultural Fairgrounds.[124][125] While a 2015 MLB game in Baltimore and all games in the pandemic-shortened 2020 season (except for the NLCS and World Series) were held in closed ballparks with nominal attendance of zero, MLB instead listed the official attendance for these games as N/A, thus allowing the Worcester game to retain the record.[126] Worcester, dead last in the NL for the 1882 season and located in a city that did not meet the NL's population standards, was set to be removed from the NL at the end of the season, as was Troy.[125]

References[edit]

General[edit]

- Kendrick, Scott. "Top 10 Most Unbreakable Baseball Records". About.com Baseball. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

- Ingraham, Jim (August 20, 2009). "The top 10 most unbreakable baseball records". The Morning Journal. Retrieved December 1, 2011.

Specific[edit]

- ^ a b c d "1. Johnny Vander Meer's Back-to-Back No-Nos – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c Moore, Terence (September 7, 2011). "Ripken's iron man record unbreakable". MLB.com. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g Harkins, Bob (September 27, 2011). "Not all records are made to be broken". NBC Sports.com. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ a b "4. Cy Young's 511 Career Wins – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b "Cy Young Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ MLB: Who holds the record for most career wins? https://bolavip.com/en

- ^ "511 wins – Cy Young – Unbreakable Baseball Records". SI.com. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Wins". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Wins". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Wins Records by Baseball Almanac". Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Games Started". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Wins". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "48 complete games – Jack Chesbro (1904) – Unbreakable Baseball Records". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Games Started". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Complete Games". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Baseball Prospectus – Baseball Therapy: What Happened to the Complete Game?". December 9, 2013. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Lost Art of the Complete Game". September 4, 2015. Retrieved March 30, 2017.

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Complete Games". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved December 18, 2022.

- ^ Miller, Sam (March 21, 2019). "How many complete games will be thrown in 2019? Thirty? Ten? None?". ESPN.com. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ Staff Writer (April 15, 2022). "Dodgers: More Details Emerge in Why Clayton Kershaw Was Pulled From Perfect Game". Inside the Dodgers | News, Rumors, Videos, Schedule, Roster, Salaries And More. Retrieved October 14, 2022.

- ^ a b c "13. Walter Johnson's 110 Career Shutouts – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ "Walter Johnson Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Shutouts". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Shutouts". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Shutouts". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g Miller, Sam (March 19, 2019). "Which of baseball's most unbreakable records might actually get broken in 2019?". ESPN.com. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ McEntegart, Pete (July 23, 2006). "The 10 Spot". SI.com. Archived from the original on August 28, 2012.

- ^ "The Fans Speak Out". Baseball Digest. 65 (5). Lakeside Publishing: 7. July 2006. ISSN 0005-609X. Retrieved June 9, 2009.

- ^ a b c Baseball's Most Unbreakable Feats (DVD). Major League Baseball Productions. 2007. ISBN 978-0-7389-3978-0.

- ^ a b c "MLB No-Hitters". ESPN.com. Retrieved November 14, 2019.

- ^ "Max Scherzer loses perfect game with HBP in 9th but completes no-hitter". ESPN.com. June 20, 2015. Retrieved June 21, 2015.

- ^ a b "5,714 career strikeouts – Nolan Ryan – Unbreakable Baseball Records". SI.com. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ a b c "15. Nolan Ryan's 5,714 Career Strikeouts – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ "Nolan Ryan Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Strikeouts (pitching)". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ a b "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Strikeouts". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Strikeouts". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Bases on Balls". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Innings Pitched". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Wild Pitches". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Joe Oeschger stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved September 19, 2023.

- ^ Missildine, Harry (June 10, 1970). "Golden anniversary almost slips by". The Spokesman-Review. Spokane, Washington. p. 19. Retrieved September 18, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Valyo, Bill (August 17, 2007). "In good old days, pitchers just kept going and going". Sebastian Sun. p. 9. Retrieved September 19, 2023 – via Newspapers.com.

- ^ Corbett, Warren (2015). "May 1, 1920: An extreme exercise in futility: Braves, Dodgers play 26 innings to no decision". Society for American Baseball Research. Retrieved September 18, 2023.

- ^ a b "12. Pete Rose's 4,256 Career Hits – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Active Leaders & Records for Hits". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b c d e Harkins, Bob (September 27, 2011). "Not all records are made to be broken". NBC Sports.com. Archived from the original on November 29, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ "Ichiro Suzuki: Japanese Leagues Statistics". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved October 4, 2015.

- ^ Anderson, r.J. (November 28, 2022). "Miguel Cabrera confirms plans to retire after 2023 season, but wants to stay in baseball". CBSSports.com. Retrieved September 3, 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Kelly, Matt (January 8, 2023). "These MLB records might be unbreakable". MLB.com. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Total Bases". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ a b "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Hits". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved April 2, 2019.

- ^ a b Miller, Sam (February 8, 2018). "Why no one will hit .400 ever again". ESPN.com. Retrieved February 9, 2018.

- ^ "6. Ichiro Suzuki, 10 Straight 200-Hit Seasons – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ "Ichiro Suzuki Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ "Hits Records by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved December 3, 2011.

- ^ Baseball's Top 100: The Game's Greatest Records, p.46, Kerry Banks, 2010, Greystone Books, Vancouver, BC, ISBN 978-1-55365-507-7

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Hits". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "77 MLB records that will never be broken". Bleacher Report. bleacherreport.com. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "Tris Speaker Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Doubles". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved May 13, 2022.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Doubles". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ "Sam Crawford Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Triples". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Triples". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 2, 2024.

- ^ Fiore, Gary (June 28, 2011). "Jose Reyes on track to set record for most triples in a season". SILive.com. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ a b c "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Triples". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved May 5, 2012.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Intentional Bases on Balls". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ Justin Verlander blames MLB for juiced balls, home run spike: 'Major League Baseball's turning this game into a joke'

- ^ Long, Jack (April 30, 1999). "Tatis' grand slam record not likely to be broken". cnnsi.com. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Two Grand Slams in One Game". www.baseball-almanac.com. Archived from the original on April 2, 2013. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Two Home Runs in One Inning". www.mlb.com. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "Incredible Performances in Texas League History". www.milb.com. Retrieved March 19, 2013.

- ^ "11. Ty Cobb's .367 Career Average – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ "Ty Cobb Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ "Ty Cobb". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved April 30, 2021.

- ^ ".366 lifetime batting average – Ty Cobb – Unbreakable Baseball Records". SI.com. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Batting Average". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved October 1, 2020.

- ^ "Royals 1-6 Marlins". ESPN. Retrieved June 6, 2023.

- ^ "Luis Arraez Stats, Fantasy & News". MLB.com. Retrieved October 3, 2023.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for Runs Scored". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved February 19, 2023.

- ^ a b ".482 lifetime on-base percentage – Ted Williams – Unbreakable Baseball Records". Sports Illustrated. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ "Hall of Famers: Williams, Ted". National Baseball Hall of Fame and Museum. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ a b "Career Leaders & Records for On-Base%". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ "Single-Season Leaders & Records for On-Base%". Baseball-Reference. Retrieved November 1, 2012.

- ^ Baseball Reference: Willie Keeler

- ^ Baseball Reference: Single-Season Leaders & Records for AB per SO

- ^ Baseball Reference: Mike McGeary

- ^ a b Batting Leaderboards: Single-Season Leaders & Records for Games Played, baseball-reference.com

- ^ "Hideki Matsui Stats". Baseball Almanac. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ a b Lauing, Jacob (September 30, 2016). "MLB sees first tie game in a very, very long time". Mashable. Retrieved November 16, 2020.

- ^ a b c "2. Cal Ripken, Jr.'s Consecutive-Games Streak – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ a b c d Harkins, Bob (September 27, 2011). "Not all records are made to be broken". NBC Sports.com. Archived from the original on November 28, 2011. Retrieved November 28, 2011.

- ^ Kepner, Tyler (April 17, 2011). "Ups and Downs of Two Top Picks". The New York Times. p. SP2. Archived from the original on April 28, 2011.

- ^ "Joe DiMaggio Hitting Streak by Baseball Almanac". Baseball-almanac.com. Retrieved February 20, 2011.

- ^ a b "9. Joe DiMaggio's 56-Game Hitting Streak – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ "56 game hitting streak – Joe DiMaggio (1941) – Unbreakable Baseball Records". SI.com. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ Stark, Jayson (May 15, 2011). "Baseball's unbreakable record". ESPN.com. Retrieved November 26, 2011.

- ^ "Does Ted Williams Own A More Impressive Streak Than Joe DiMaggio?".

- ^ a b Newsday, 20 fun facts about Joe DiMaggio's 56-game hit streak

- ^ Bleacher Report, Open Mic: Joe DiMaggio's 56-Game Hit Streak Is One Record That Will Go Untouched

- ^ "Wes Ferrell Baseball Stats | Baseball Almanac".

- ^ "Earl Wilson Baseball Stats | Baseball Almanac".

- ^ "Shohei Ohtani Stats".

- ^ "Sacrifice Hits All Time Leaders on Baseball Almanac".

- ^ "Career Leaders & Records for Sacrifice Hits". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved March 11, 2022.

- ^ a b "17. Rickey Henderson's 1,406 Career Steals – Unbreakable Baseball Records". LIFE.com. See Your World LLC. Archived from the original on May 5, 2010.

- ^ "Rickey Henderson Statistics and History". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved November 27, 2011.

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Stolen Bases". Baseball-Reference.com. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Stolen Bases". Baseball-Reference. Sports Reference LLC. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ "Stealing Home Base Records | Baseball Almanac".

- ^ Chuck Klein, Baseball-reference.com

- ^ "Year-by-Year Top-Tens Leaders & Records for Assists as OF". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved November 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Career outfield assist leaders, Baseball-reference.com

- ^ "Active Leaders & Records for Errors Committed". Baseball-Reference.com. Retrieved January 3, 2024.

- ^ a b "Most All-Star Games: 25 – Hank Aaron – Unbreakable Baseball Records". SI.com. Retrieved November 27, 2011.