Lurie Garden

| Lurie Garden | |

|---|---|

Historic Michigan Boulevard District and Randolph Street streetwalls from Lurie Garden | |

| |

| Type | Public Garden |

| Location | Millennium Park Chicago, Illinois |

| Coordinates | 41°52′53.33″N 87°37′18.45″W / 41.8814806°N 87.6217917°W |

| Area | 5-acre (20,234 m2) (2.5 planted)[1] |

| Created | July 16, 2004 |

| Operated by | City of Chicago |

| Visitors | Free Public |

| Status | Open year round |

| Parking | 2218 (Millennium Park parking garage)[2] |

| Public transit access | |

Lurie Garden is a 2.5-acre (10,000 m2) garden located at the southern end of Millennium Park in the Loop area of Chicago in Cook County, Illinois, United States. Designed by GGN (Gustafson Guthrie Nichol), Piet Oudolf, and Robert Israel,[3] it opened on July 16, 2004. The garden is a combination of perennials, bulbs, grasses, shrubs and trees.[4] It is the featured nature component of the world's largest green roof. The garden cost $13.2 million and has a $10 million endowment for maintenance and upkeep.[5][6] It was named after Ann Lurie, who donated the $10 million endowment.[7][8] For visitors, the garden features guided walks, lectures, interactive demonstrations, family festivals and picnics.[9]

The Garden is composed of two "plates" protected on two sides by large hedges. The dark plate depicts Chicago's history by presenting shade-loving plant material. The dark plate has a combination of trees that will provide a shade canopy for these plants when they fill in. The light plate, which includes no trees, represents the city's future with sun-loving perennials that thrive in the heat and the sun.[10]

General information[edit]

Lying between Lake Michigan to the east and the Loop to the west, Grant Park has been Chicago's front yard since the mid 19th century. Its northwest corner, north of Monroe Street and the Art Institute, east of Michigan Avenue, south of Randolph Street, and west of Columbus Drive, had been Illinois Central rail yards and parking lots until 1997, when it was made available for development by the city as Millennium Park.[11] Today, Millennium Park trails only Navy Pier as a Chicago tourist attraction.[12] Today, there is truly a rooftop garden on top of the Millennium Park parking garage, which is itself above railroad tracks.[9]

In 1836, a year before Chicago was incorporated,[13] the Board of Canal Commissioners held public auctions for the city's first lots. Foresighted citizens, who wanted the lakefront kept as public open space, convinced the commissioners to designate the land east of Michigan Avenue between Randolph Street and Park Row (11th Street) "Public Ground—A Common to Remain Forever Open, Clear and Free of Any Buildings, or Other Obstruction, whatever."[14] Grant Park has been "forever open, clear and free" since, protected by legislation that has been affirmed by four previous Illinois Supreme Court rulings.[15][16][17]

In 1839, United States Secretary of War Joel Roberts Poinsett declared the land between Randolph Street and Madison Street east of Michigan Avenue "Public Ground forever to remain vacant of buildings".[13] Aaron Montgomery Ward, who is known both as the inventor of mail order and the protector of Grant Park, twice sued the city of Chicago to force it to remove buildings and structures from Grant Park and to keep it from building new ones.[18][19] In 1890, arguing that Michigan Avenue property owners held easements on the park land, Ward commenced legal actions to keep the park free of new buildings. In 1900, the Illinois Supreme Court concluded that all landfill east of Michigan Avenue was subject to dedications and easements.[20] In 1909, when he sought to prevent the construction of the Field Museum of Natural History in the center of the park, the courts affirmed his arguments.[21][22] As a result, the city has what are termed the Montgomery Ward height restrictions on buildings and structures in Grant Park and there are no tall buildings in the park blocking the sun for large parts of the day.

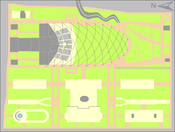

The Lurie garden constantly depicts the dynamics of nature, but it is most colorful from June through the autumn. It is not a botanical garden with a scientific purpose and is instead a public garden. Thus, it does not use a plant labeling system. The plant life of the garden consists entirely of perennials. It does not now nor does it intend to incorporate annuals, which rarely survive Chicago winters. Approximately 60% of the plant life in the light and dark plates are plants that are native to Illinois.[10] It is located across the street from the Art Institute of Chicago's new Modern Wing, and within the park it is south of Jay Pritzker Pavilion, east of the South Chase Promenade and Southwest Exelon Pavilion as well as the future site of the Nichols Bridgeway, west of the Southeast Exelon Pavilion, southwest of the BP Pedestrian Bridge.

Culture[edit]

The garden was an essential element of the park, as the motto of Chicago is Urbs in Horto, which is a Latin phrase meaning City in a Garden.[3] The Garden also pays tribute to Carl Sandburg's moniker of Chicago as the "City of Big Shoulders" with a 15-foot (4.6 m) "shoulder" hedge that protects the perennial garden and encloses the park on two sides.[3] It keeps the garden from being trampled by crowds exiting events at the neighboring Jay Pritzker Pavilion.[23]

The "shoulder" hedge, which serves as the northern edge of the garden, also fills the space next to the void of the great lawn of the Jay Pritzker Pavilion. These hedges use a metal armature, to prefigure the mature hedge.[6] The shoulder hedge is an evolving hedge screen of deciduous Fagus (beech) and Carpinus (hornbeam) and evergreen Thuja (arborvitae, also known as redcedars) that will eventually (over the course of approximately ten years) branch horizontally to fill the permanent armature frame and create a solid hedge.[10]

The garden was one of the gardens depicted in the 2006 In Search of Paradise: Great Gardens of the World exhibition that was shown from May 12 – October 22, 2006 in the Boeing Galleries and that was later shown in the Chicago Botanic Garden. The Chicago Botanic Garden developed the exhibition that included 65 photomurals of gardens from 21 countries using photographs that were less than five years old.[24]

Design[edit]

Seattle-based landscape architecture firm GGN and Israel, a renowned lighting and set designer,[7] determined the thematic concepts such as the placement of paths and the shapes of perennial beds.[6] Oudolf, a Dutch perennial plantsman,[7] designed the flower beds which contain 26,000 perennial plants in 250 varieties native to the prairie.[6] The garden is designed with four primary components: the shoulder hedge, the light plate, the dark plate and the seam boardwalk.[25]

The shoulder hedge frames the garden's north and west sides,[25] and the hedge and armature help to protect the perennials from heavy pedestrian traffic.[26] The 14-foot (4.3 m) armature also provides a permanent pruning guide.[26] In addition to the Carl Sandburg symbolism, the western hedge also forms a topiary referring to greek mythology.[26]

Lurie Garden is bisected by a diagonal boardwalk, which represents the natural Lake Michigan seawall that still bisects Grant Park. The boardwalk divides the garden into two plates, one of which contains muted colors, the other bright colors,[6] while paralleling the line of the old Illinois Central Railroad retaining wall.[8] The dark plate represents the early landscape history of the site, while the light plate represents the landscape of the future.[25] The diagonal plate-dividing seam boardwalk serves as a demarcation between two eras of Chicago's landscape development.[25] It also serves as a reminder of the time when Chicago placed boards over the marshland for pedestrians.[1]

The boardwalk has a 24-inch (61 cm) wide step[26] on one side. The step, which provides seating,[9] leads down to a 5-foot (1.5 m) wide canal, which runs between this step and a limestone wall.[7] The limestone supports the plant beds of the dark plate.[9] The water is invigorated with jets, and visitors are allowed to sit and dangle their feet in the water.[7] It traces the angle of a historic subterranean seawall that remains beneath the site and used to be the boundary between the marshy Lake Michigan shoreline and the city.[25] The boardwalk also crosses over stepped pools that expose a 5-foot (1.5 m) wide seam of water.

The garden initially had a hardwood footbridge that passes over the shallow water in the canal, and that divides the garden diagonally.[3] However, stories in the sixth year of the garden described steel bridges.[9] The entire garden slopes downward to present itself for the new Renzo Piano Modern Wing addition to the Art Institute of Chicago Building.[6][23] At the foot of the canal opposite the Building the water ends in a pool.[9] Israel's lighting accents the hedges, and pathways are lit by in-ground lighting fixtures.[26] There were complaints that the construction of the Nichols Bridgeway clutters the picturesque view of Lurie Gardens and in so doing diminishes its prairie aspect.[27]

Materials[edit]

The garden is a sustainable design built on lightweight geofoam under the soil. All curbing, stone stairways, stair landings, wall coping, and wall cladding in the interior of the Garden use midwestern limestone. The garden uses granite for paving and wall veneer. Where it is exposed, the granite surfaces have a flamed finish. The boardwalk and wood benches in the Garden are fabricated from FSC-certified Ipe. The garden primarily uses patinized Naval Brass (all metal plates in the Seam), patinized architectural bronze (all handrails), and powdercoated steel (the armature).[28]

Wildlife features[edit]

The seasonal highlights are as follows: Spring highlights include - Star of Persia, Arkansas Blue Star, Wild White Indigo, Quamash, Shooting Star, Prairie Smoke, Virginia Bluebells, Herbaceous Peony, Phlomis, Meadow Sage, Burnet, and Tulip; Summer highlights include - Giant Hyssop, Ornamental Onion, Butterfly Weed, Purple Lance Astilbe, Calamint, Rusty Foxglove, Pale Coneflower, Daylily, White Blazing Star, Bee Balm, Oregano, and Culver's Root; Fall/Winter highlights include - Japanese Anemone, White Wood Aster, Northern Sea Oats, Tennessee Coneflower, Purple Love Grass, Rattlesnake Master, Bottle Gentian, Common Eulalia Grass, Red Switch Grass, Little Bluestem, Prairie Dropseed, and Toad Lily.[29] The garden features dozens of types of perennials and bulbs.[30] The garden features both ornamental and prairie grasses.[31] It includes evergreen and deciduous shrubs.[32] Its trees serve as its foundation.[33] The wide variety of plant life has lured dozens of cottontail rabbits to the Garden and the surrounding park.[34] The garden uses no synthetic pesticides.[1]

60,000 and 42,000 bulbs were handplanted in 2006 and 2008, respectively.[1] In 2009, 20,000 additional bulbs were planted, bringing the total to 120,000 and extending the flowering season earlier.[9] The garden includes 35,000 perennials in 240 varieties and 5,200 "woody" plants in 14 varieties.[1]

The dark plate's perennials include ferns, angelicas and other broad-leaved species, with a scattering of trees sprouting out of the flower beds.[9] These plants thrive with shade from trees.[1] The lush plants of this plate were selected by Oudolf as a tribute to Chicago's marshy beginnings.[23] It is described as a thick wetland whose designers have described as "wild, naughty and hidden."[9]

The light plate is dominated by prairie plants: grasses, coneflowers, prairie-smoke and no trees.[9] These plants thrive in direct sunlight.[1] This plate unites lighter native plants with imported specimens.[23] It is described as a fine-textured upland whose designers have described as "clean, noble and prominent".[9]

At the time of the 2004 opening of the Garden, the perennials were expected to need a year or two to mature and the hedges were expected to need another five to ten years to fill out.[23] Another Tribune critic, Beth Botts, noted that the historical symbolism of the plantings is a future pleasure to be anticipated. However, she noted that it would be many years before the rosebud trees to the east could provide a pleasant shade.[8] By the July/August 2010 issue of Garden Design, the garden was described as a garden in maturity worth revisiting.[9]

Several animal species have been sighted in the garden. 27 species of birds have been identified in the park and its garden. Butterflies and bees have are among the wildlife that visit the garden.[1]

Visitor programming[edit]

In 2008, the garden hosted four million visitors from 21 countries. In its first few years, it has had over two dozen adult programs attended by 1,800 people each year and over three dozen family programs attended by 5,000 people per year. The garden participated in an "Ask Me" program in 2009, during which 12 volunteers logged 192 hours answering questions from 1,094 guests from 35 states and 20 countries as well as a series of 2009 Sunday Garden Tours in which 24 people volunteered 391 hours to guide 2,027 guests from 45 states and 26 countries through the garden. During 2009, eight volunteers spent 383 hours gardening. The garden has two staff members and four volunteers on hand to answer questions on Wednesdays and Thursdays. The garden is open from Memorial Day through Labor Day from 10 a.m. to 11 p.m. on weekdays and from 6 a.m. to 11 p.m. on weekends.[1]

Critical review[edit]

Chicago Tribune Pulitzer Prize-winning architecture critic Blair Kamin, rated the garden as three stars, but projected it to be a four star venue once mature. He praised the light plate especially for its vibrant composition and undulating garden as a fitting contrast to the historic Chicago skyline. He also praised the symbolism of the seam for its uniqueness. He considers the garden a testament to the value of urban planning of public spaces.[23] Botts noted that the reward of a design awaiting maturity is in enjoying the maturation.[8]

Awards[edit]

The garden is the result of an invited international competition that occurred from August to October 2000. Following the contest the garden was commissioned in October 2000 and completed in June 2004.[35] Among the entrants in the competition were Louis Benech, Dan Kiley, George Hargreaves, Jeffrey Mendoza and Michael Van Valkenburgh.[7]

The garden has won numerous awards: Best Public Space Award by Travel + Leisure, 2005;[36] Intensive Industrial Award by Green Roofs for Healthy Cities, 2005;[37] Award of Honor by WASLA Professional Awards, 2005; Institute Honor Awards for Regional & Urban Design, American Institute of Architects, 2006 (Millennium Park);[36] and Award of Excellence, American Society of Landscape Architects Professional Awards, 2008.[28]

Green Roofs for Healthy Cities considers the park to be the largest green roof in the world as it covers a structural deck supported by two reinforced concrete cast-in-place garages and steel structures that span the space above Illinois Central Railroad tracks.[25][38]

Notes[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Markgraf, Sue (March 7, 2010). "Lurie Garden Fact Sheet". GreenMark Public Relations, Inc. Archived from the original on July 27, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "A no place transformed into a grand space – What was once a gritty, blighted site is now home to a glistening, cultural spectacle that delivers joy to its visitors". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved August 6, 2008.

- ^ a b c d "Art & Architecture: Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: The Plant Life of the Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on June 4, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Herrmann, Andrew (July 15, 2004). "Sun-Times Insight". Chicago Sun-Times. Newsbank. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Freemen, Allen (November 2004). "Fair Game on Lake Michigan". Landscape Architecture Magazine. American Society of Landscape Architects. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f Raver, Anne (July 15, 2004). "Nature; Softening a City With Grit and Grass". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c d Botts, Beth (July 15, 2004). "Glimpsing a garden: From the ground up: Lurie will take time to reach potential". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l Arvidson, Adam Regn (July–August 2010). "Lurie Garden: Rooftop Wonder" (PDF). Garden Design. Archived from the original (PDF) on July 27, 2011. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ a b c "Frequently Asked Questions". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on June 22, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2008.

- ^ Gilfoyle, Timothy J. (August 6, 2006). "Millennium Park". The New York Times. Retrieved June 24, 2008.

- ^ "Crain's List Lartgest Tourist Attractions (Sightseeing): Ranked by 2007 attendance". Crain's Chicago Business. Crain Communications Inc. June 23, 2008. p. 22.

- ^ a b Macaluso, pp. 12–13

- ^ Gilfoyle, pp. 3–4

- ^ Spielman, Fran (June 12, 2008). "Mayor gets what he wants – Council OKs move 33–16 despite opposition". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved November 16, 2009.

- ^ "The taking of Grant Park". Chicago Tribune. June 8, 2008. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Spielman, Fran and Art Golab (May 16, 2008). "13–2 vote for museum – Decision on Grant Park sets up Council battle". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved July 29, 2008.

- ^ Grinnell, Max (2005). "Grant Park". The Electronic Encyclopedia of Chicago. Chicago Historical Society. Retrieved July 28, 2008.

- ^ Macaluso, pp. 23–25

- ^ City of Chicago v. A Montgomery Ward, 169 Ill. 392 (1897)

- ^ Gilfoyle, p. 16

- ^ E. R. Bliss v. A. Montgomery Ward, 198 Ill. 104; A. Montgomery Ward v. Field Museum of Natural History, 241 Ill. 496 (1909); and South Park Commissioners v. Ward & Co., 248 Ill. 299

- ^ a b c d e f Kamin, Blair (July 18, 2004). "Lurie Garden (star)(star)(star): Monroe and Columbus Drives: Kathryn Gustafson, Seattle in collaboration with Piet Oudolf, Hummelo, the Netherlands and Robert Israel, Los Angeles". Chicago Tribune. Retrieved July 16, 2010.

- ^ Hurwitz, Jill (April 28, 2006). "In Search Of Paradise: Great Gardens Of The World" (PDF). City of Chicago. Archived from the original (PDF) on September 29, 2006. Retrieved June 11, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e f "Contemporary Urban Waterscapes: designing public spaces in concert with nature". Archived from the original on May 17, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b c d e "Art & Architecture: The Lurie Garden Design Narrative". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on May 28, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Voice of the People (Letters)". Chicago Tribune. Newsbank. May 15, 2008. Retrieved June 5, 2008.

- ^ a b "General Design Award Of Excellence". American Society of Landscape Architects. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: The Plant Life of the Lurie Garden - Seasonal Highlights". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on November 5, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: The Plant Life of the Lurie Garden - Perennials and Bulbs of the Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: The Plant Life of the Lurie Garden - Grasses of the Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: The Plant Life of the Lurie Garden - Shrubs of the Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: The Plant Life of the Lurie Garden - Trees of the Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on November 4, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Herrmann, Andrew (May 21, 2005). "Millennium Park snafus multiplying like rabbits // 100 have been caught in 4 months, but they breed 5 times a year". Chicago Sun-Times. Retrieved May 28, 2009.

- ^ "Art & Architecture: Facts and Dimensions of The Lurie Garden". City of Chicago. Archived from the original on April 15, 2008. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ a b "The Lurie Garden". ggnltd.com. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ "Awards". Green Roofs for Healthy Cities. 2005. Archived from the original on November 23, 2007. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

- ^ Bernstein, Fred A. (July 18, 2004). "Art/Architecture; Big Shoulders, Big Donors, Big Art". The New York Times. Retrieved June 1, 2008.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- City of Chicago Millennium Park

- Millennium Park map

- City of Chicago Loop Community Map