Lyrical abstraction

This article has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these template messages)

|

Lyrical abstraction is either of two related but distinct trends in Post-war Modernist painting:

European Abstraction Lyrique born in Paris, the French art critic Jean José Marchand being credited with coining its name in 1947, considered as a component of Tachisme when the name of this movement was coined in 1951 by Pierre Guéguen and Charles Estienne the author of L'Art à Paris 1945–1966, and American Lyrical Abstraction a movement described by Larry Aldrich (the founder of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield Connecticut) in 1969.[2][3]

A second definition is the usage as a descriptive term. It is a descriptive term characterizing a type of abstract painting related to Abstract Expressionism; in use since the 1940s. Many well known abstract expressionist painters such as Arshile Gorky seen in context have been characterized as doing a type of painting described as lyrical abstraction.[4][5][6]

Origin[edit]

The original common use refers to the tendency attributed to paintings in Europe during the post-1945 period and as a way of describing several artists (mostly in France) with painters like Wols, Gérard Schneider and Hans Hartung from Germany or Georges Mathieu, etc., whose works related to characteristics of contemporary American abstract expressionism. At the time (late 1940s), Paul Jenkins, Norman Bluhm, Sam Francis, Jules Olitski, Joan Mitchell, Ellsworth Kelly, and numerous other American artists were, as well, living and working in Paris and other European cities. With the exception of Kelly, all of those artists developed their versions of painterly abstraction that has been characterized at times as lyrical abstraction, tachisme, color field, Nuagisme and abstract expressionism.

The art movement Abstraction lyrique was born in Paris after the war. At that time, the artistic life in Paris, which had been devastated by the Occupation and Collaboration, resumed with numerous artists exhibited again as soon as the Liberation of Paris in mid-1944. According to the new abstraction forms that characterised some artists, the movement was named by the art critic, Jean José Marchand, and the painter, Georges Mathieu, in 1947. Some art critics also looked at this movement as an attempt to restore the image of artistic Paris, which had held the rank of capital of the arts until the war. Lyrical abstraction also represented a competition between the School of Paris and the new New York School of Abstract Expressionism painting represented above all since 1946 by Jackson Pollock, then Willem de Kooning or Mark Rothko, which were also promoted by the American authorities from the early 1950s.

Lyrical abstraction was opposed not only to the Cubist and Surrealist movements that preceded it, but also to geometric abstraction (or "cold abstraction"). Lyrical abstraction was, in some ways, the first to apply the lessons of Wassily Kandinsky, considered one of the fathers of abstraction. For the artists, lyrical abstraction represented an opening to personal expression.

Finally, in the late 1960s (partially as a response to minimal art, and the dogmatic interpretations by some to Greenbergian and Juddian formalism), many painters re-introduced painterly options into their works and the Whitney Museum and several other museums and institutions at the time formally named and identified the movement and uncompromising return to painterly abstraction as 'lyrical abstraction'.

European abstraction lyrique[edit]

Just after World War II, many artists old and young were back in Paris where they worked and exhibited: Nicolas de Staël, Serge Poliakoff, André Lanskoy and Zaks from Russia; Hans Hartung and Wols from Germany; Árpád Szenes, Endre Rozsda and Simon Hantaï from Hungary; Alexandre Istrati from Romania; Jean-Paul Riopelle from Canada; Vieira da Silva from Portugal; Gérard Ernest Schneider from Switzerland; Feito from Spain; Bram van Velde from the Netherlands; Albert Bitran from Turkey; Zao Wou-Ki from China; Sugai from Japan; Sam Francis, John Franklin Koenig, Jack Youngerman and Paul Jenkins from the U.S.A and Yehezkel Streichman from Israel.

All these artists and many others were at that time among the "Lyrical Abstractionists" with the French: Pierre Soulages, Jean-Michel Coulon, Jean René Bazaine, Jean Le Moal, Gustave Singier, Alfred Manessier, Roger Bissière, Pierre Tal-Coat, Jean Messagier, Jean Miotte, and others.

Lyrical Abstraction was opposed not only to "l'Ecole de Paris" remains of pre-war style but to Cubist and Surrealist movements that had preceded it, and also to geometric abstraction (or "Cold Abstraction"). For the artists in France, Lyrical Abstraction represented an opening to personal expression. In Belgium, Louis Van Lint figured a remarkable example of an artist who, after a short period of geometric abstraction, has moved to a lyrical abstraction in which he excelled.

Many exhibitions were held in Paris for example in the galleries Arnaud, Drouin, Jeanne Bucher, Louis Carré, Galerie de France, and every year at the "Salon des Réalités Nouvelles" and "Salon de Mai" where the paintings of all these artists could be seen. At the Drouin gallery one could see Jean Le Moal, Gustave Singier, Alfred Manessier, Roger Bissière, Wols and others. A wind blew over the capital when Georges Mathieu decided to hold two exhibitions: L'Imaginaire in 1947 at the Palais du Luxembourg which he would have prefer to call abstraction lyrique to impose the name and then HWPSMTB with (Hans Hartung, Wols, Francis Picabia, François Stahly sculptor, Georges Mathieu, Michel Tapié, and Camille Bryen) in 1948.

In March 1951 was held the larger exhibition Véhémences confrontées in the gallery Nina Dausset where for the first time were presented side to side French and American abstract artists. It was organised by the critic Michel Tapié, whose role in the defense of this movement was of the highest importance. With these events, he déclared that « the lyrical abstraction is born ».

It was, however, a fairly short reign (late 1957), which was quickly supplanted by the New Realism of Pierre Restany and Yves Klein.

Starting around 1970, this movement has been revived by a new generation of artists born during or immediately after the Second World War. Some of its key promoters include Paul Kallos, Georges Romathier, Michelle Desterac, and Thibaut de Reimpré.

An exhibition entitled "The Lyrical Flight, Paris 1945–1956" (L'Envolée Lyrique, Paris 1945–1956), bringing together the works of 60 painters, was presented in Paris at the Musée du Luxembourg from April to August 2006 and included the most prominent painters of the movement: Georges Mathieu, Pierre Soulages, Gérard Schneider, Zao Wou-Ki, Albert Bitran, Serge Poliakoff.[7]

Artists in Paris (1945–1956) and beyond[edit]

- Geneviève Asse (1923–2021)

- Mino Argento (1927– )[8]

- Jean René Bazaine (1904–2001)

- Roger Bissière (1888–1964) [9]

- Albert Bitran (1931–2018)

- Norman Bluhm[10] (1921–1999)

- Alexander Bogen (1916–2010)

- Camille Bryen (1907-1977)

- Jean-Michel Coulon (1920–2014)

- Olivier Debré (1920–1999)

- Piero Dorazio (1927–2005)

- Joe Downing (1925–2007)

- Jean Dubuffet (1901–1985)

- Endre Rozsda (1913–1999)

- Bracha Ettinger (1948– )

- Jean Fautrier (1898–1964)

- Pierre Fichet (1927–2007)

- Francois Fiedler (1921–2001)

- Sam Francis[11](1923–1994)

- Annick Gendron (1939–2008)

- Marc-Antoine Goulard (1964– )

- Hans Hartung (1904–1989)

- Simon Hantaï (1922–2008)

- Alexandre Istrati (1915–1991)

- Paul Jenkins[11] (1923–2012)

- Antoni Karwowski (1948– )

- John Franklin Koenig (1924–2008)

- André Lanskoy (1902–1976)

- Alfred Manessier (1911–1993)

- René Marcil (1917–1993)

- Georges Mathieu (1921–2012)

- Jean Messagier (1920–1999)

- Jean Miotte (1926–2016)

- Joan Miró (1893–1983)[12]

- Francis Picabia (1879–1953)

- Serge Poliakoff (1906–1969)

- Thibaut de Reimpré (1949– )

- Seund Ja Rhee (1918–2009)

- Jean-Paul Riopelle (1923–2002)[10]

- Emilio Scanavino, (1922–1986)

- Vieira da Silva (1908–1992)

- Gustave Singier (1909–1984)

- Pierre Soulages (1919–2022)

- Nicolas de Staël (1914–1955)

- Yehezkel Streichman (1906–1993)

- Árpád Szenes (1897–1985)

- Gérard Ernest Schneider (1896–1986)

- Michel Tapié (1909–1987)

- Bram van Velde (1895–1981)

- François Willi Wendt (1909–1970)

- Wols, pseudonym of Alfred Otto Wolfgang Schulze (1913–1951)

- Zao Wou-Ki (1921–2013)

- Fahrelnissa Zeid (1901–1991)

United States[edit]

American Lyrical Abstraction is an art movement[14] that emerged in New York City, Los Angeles, Washington, DC, and then Toronto and London during the 1960s–1970s. Characterized by intuitive and loose paint handling, spontaneous expression, illusionist space, acrylic staining, process, occasional imagery, and other painterly and newer technological techniques.[15] Lyrical Abstraction led the way away from minimalism in painting and toward a new freer expressionism.[16] Painters who directly reacted against the predominating Formalist, Minimalist, and Pop Art and geometric abstraction styles of the 1960s, turned to new, experimental, loose, painterly, expressive, pictorial and abstract painting styles. Many of them had been Minimalists, working with various monochromatic, geometric styles, and whose paintings publicly evolved into new abstract painterly motifs. American Lyrical Abstraction is related in spirit to Abstract Expressionism, Color Field painting and European Tachisme of the 1940s and 1950s as well. Tachisme refers to the French style of abstract painting current in the 1945–1960 period. Very close to Art Informel, it presents the European equivalent to Abstract Expressionism.

The Sheldon Museum of Art held an exhibition from 1 June until 29 August 1993 entitled Lyrical Abstraction: Color and Mood. Some of the participants included Dan Christensen, Walter Darby Bannard, Ronald Davis, Helen Frankenthaler, Sam Francis, Cleve Gray, Ronnie Landfield, Morris Louis, Jules Olitski, Robert Natkin, William Pettet, Mark Rothko, Lawrence Stafford, Peter Young and several other painters. At the time the museum issued a statement the read in part:

As a movement, Lyrical Abstraction extended the post-war Modernist aesthetic and provided a new dimension within the abstract tradition which was clearly indebted to Jackson Pollock's "dripped painting" and Mark Rothko's stained, color forms. This movement was born out of a desire to create a direct physical and sensory experience of painting through their monumentality and emphasis on color – forcing the viewer to "read" paintings literally as things.[17]

During 2009 the Boca Raton Museum of Art in Florida hosted an exhibition entitled Expanding Boundaries: Lyrical Abstraction Selections from the Permanent Collection

At the time the museum issued a statement that said in part:

Lyrical Abstraction arose in the 1960s and 70s, following the challenge of Minimalism and Conceptual art. Many artists began moving away from geometric, hard-edge, and minimal styles, toward more lyrical, sensuous, romantic abstractions worked in a loose gestural style. These "lyrical abstractionists" sought to expand the boundaries of abstract painting, and to revive and reinvigorate a painterly 'tradition' in American art. At the same time, these artists sought to reinstate the primacy of line and color as formal elements in works composed according to aesthetic principles – rather than as the visual representation of sociopolitical realities or philosophical theories.

Characterized by intuitive and loose paint handling, spontaneous expression, illusionist space, acrylic staining, process, occasional imagery, and other painterly techniques, the abstract works included in this exhibition sing with rich fluid color and quiet energy. Works by the following artists associated with Lyrical Abstraction will be included: Natvar Bhavsar, Stanley Boxer, Lamar Briggs, Dan Christensen, David Diao, Friedel Dzubas, Sam Francis, Dorothy Gillespie, Cleve Gray, Paul Jenkins, Ronnie Landfield, Pat Lipsky, Joan Mitchell, Robert Natkin, Jules Olitski, Larry Poons, Garry Rich, John Seery, Jeff Way and Larry Zox.[11]

History of the term in America[edit]

Lyrical Abstraction, an exhibition in the Whitney Museum of American Art, May 25–July 6, 1971 was described by John I. H. Baur, curator of the Whitney Museum of American Art:[18]

To be given an entire exhibition surveying a current trend in American art at a single blow is an experience unusual to the verge of the bizarre ... Mr. Aldrich defines the trend of Lyrical Abstraction and explains how he came to acquire the works ...

Lyrical Abstraction was the title of a circulating exhibition which commenced at the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Connecticut from April 5 through June 7, 1970,[19] and ended at the Whitney Museum of American Art, New York, May 25 through July 6, 1971.[20] Lyrical Abstraction is a term that was used by Larry Aldrich (the founder of the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield Connecticut) in 1969 to describe what Aldrich said he saw in the studios of many artists at that time.[2][21] Mr. Aldrich, a successful designer and art collector, defined the trend of Lyrical Abstraction and explained how he came to acquire the works.[22] In his "Statement of the Exhibition" he wrote,

Early last season, it became apparent that in painting there was a movement away from the geometric, hard-edge, and minimal, toward more lyrical, sensuous, romantic abstractions in colors which were softer and more vibrant ... The artist's touch is always visible in this type of painting, even when the paintings are done with spray guns, sponges or other objects ... As I researched this lyrical trend, I found many young artists whose paintings appealed to me so much that I was impelled to acquire many of them. The majority of the paintings in the Lyrical Abstraction exhibition were created in 1969 and all are a part of my collection now.

Larry Aldrich donated the paintings from the exhibition to the Whitney Museum of American Art.[23]

For many years the term Lyrical Abstraction was a pejorative, which unfortunately adversely affected those artists whose works were associated with that name. In 1989 Union College art history professor, the late Daniel Robbins observed that Lyrical Abstraction was the term used in the late 1960s to describe the return to painterly expressivity by painters all over the country and "consequently", Robbins said, "the term should be used today because it has historical credibility"[24]

Exhibition participants[edit]

The following artists participated in the exhibition Lyrical Abstraction.[25][26]

- Helene Aylon (1931–2020)

- Victoria Barr (1937– )

- James Beres (1942–2014)

- Jake Berthot (1939–2014)

- Dan Christensen[11] (1942–2007)[27][28]

- David William Cummings (1937–2019)

- Carl Gliko (1941– )

- John Adams Griefen (1942– )

- Carol Haerer (1933–2002)

- Gary Hudson (1936–2009)

- Don Kaufman (1935– )

- Jane A. Kaufman (1938– )

- Victor Kord (1935– )

- Ronnie Landfield[11][27](1947– )[29][30][31][32]

- Pat Lipsky[11] (1941– )

- Ralph Moseley (1941– )

- David Paul (1945– ) only in 1970

- Herbert Perr,(1941– )

- William Pettet (1942–2019)

- Murray Reich (1932–2012)

- Garry Lorence Rich (1943–2016)

- Ken L. Showell (1939–1997)[29][32]

- John Seery[11][28][33](1941– )

- Alan Siegel (1938– )

- Lawrence Stafford (1938– )[32]

- William Staples (1934– )

- James Sullivan (artist) (1939– )

- Herbert Schiffrin (1944– )

- Shirlann Smith (1931– )

- John Torreano (1941– )

- Jeff Way (1942– )

- Thornton Willis (1936– )

- Philip Wofford (1935– )[29][32]

- Robert Zakanitch (1935– )

Relation to other tendencies[edit]

Lyrical Abstraction along with the Fluxus movement and Postminimalism (a term first coined by Robert Pincus-Witten in the pages of Artforum in 1969)[34] sought to expand the boundaries of abstract painting and Minimalism by focusing on process, new materials and new ways of expression. Postminimalism often incorporating industrial materials, raw materials, fabrications, found objects, installation, serial repetition, and often with references to Dada and Surrealism is best exemplified in the sculptures of Eva Hesse.[34] Lyrical Abstraction, Conceptual Art, Postminimalism, Earth Art, Video, Performance art, Installation art, along with the continuation of Fluxus, Abstract Expressionism, Color Field Painting, Hard-edge painting, Minimal Art, Op art, Pop Art, Photorealism and New Realism extended the boundaries of Contemporary Art in the mid-1960s through the 1970s.[35] Lyrical Abstraction is a type of freewheeling abstract painting that emerged in the mid-1960s when abstract painters returned to various forms of painterly, pictorial, expressionism with a focus on process, gestalt and repetitive compositional strategies in general. Characterized by an overall gestalt, consistent surface tension, sometimes even the hiding of brushstrokes, and an overt avoidance of relational composition. It developed as did Postminimalism as an alternative to strict Formalist and Minimalist doctrine.

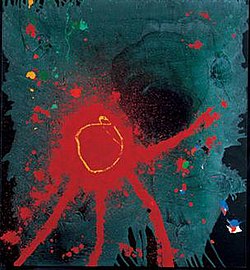

Lyrical Abstraction shares similarities with Color Field Painting and Abstract Expressionism especially in the freewheeling usage of paint – texture and surface, an example is illustrated by the painting by Ronnie Landfield entitled For William Blake. Direct drawing, calligraphic use of line, the effects of brushed, splattered, stained, squeegeed, poured, and splashed paint superficially resemble the effects seen in Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting. However the styles are markedly different. Setting it apart from Abstract Expressionism and Action Painting of the 1940s and 1950s is the approach to composition and drama. As seen in Action Painting there is an emphasis on brushstrokes, high compositional drama, dynamic compositional tension. While in Lyrical Abstraction there is a sense of compositional randomness, all over composition, low key and relaxed compositional drama and an emphasis on process, repetition, and an all over sensibility. The differences with Color Field Painting are more subtle today because many of the Color Field painters like Helen Frankenthaler, Jules Olitski, Sam Francis, and Jack Bush[36] with the exceptions of Morris Louis, Ellsworth Kelly, Paul Feeley, Thomas Downing, and Gene Davis evolved into Lyrical Abstractionists. Lyrical Abstraction shares with both Abstract Expressionism and Color Field Painting a sense of spontaneous and immediate sensual expression, consequently distinctions between specific artists and their styles become blurred, and seemingly interchangeable as they evolve.

By the mid-1950s, Richard Diebenkorn abandoned abstract expressionism and along with David Park, Elmer Bischoff and several others formed the Bay Area Figurative School with a return to Figurative painting. During the period between the fall 1964 and the spring of 1965 Diebenkorn traveled throughout Europe, he was granted a cultural visa to visit and view Henri Matisse paintings in important Soviet museums. He traveled to the then Soviet Union to study Henri Matisse paintings in Russian museums that were rarely seen outside of Russia. When he returned to painting in the Bay Area in mid-1965 his resulting works summed up all that he had learned from his more than a decade as a leading figurative painter.[37] When in 1967 he returned to abstraction his works were parallel to movements like the Color Field movement and Lyrical Abstraction.[38]

In the 1960s, English painter John Hoyland's Color field paintings were characterised by simple rectangular shapes, high-key color and a flat picture surface. In the 1970s his paintings became more textured.[39] During the 1960s and 1970s, he showed his paintings in New York City with the Robert Elkon Gallery and the André Emmerich Gallery. His paintings were closely aligned with Post-Painterly Abstraction, Color Field painting and Lyrical Abstraction.[28]

Abstract Expressionism preceded Color Field painting, Lyrical Abstraction, Fluxus, Pop Art, Minimalism, Postminimalism, and the other movements of the 1960s and 1970s and it influenced the later movements that evolved. The interrelationship of/and between distinct but related styles resulted in influence that worked both ways between artists young and old, and vice versa. During the mid-1960s in New York, Los Angeles and elsewhere artists often crossed the lines between definitions and art styles. During that period – the mid-1960s through the 1970s advanced American art and contemporary art in general was at a crossroad, shattering in several directions. During the 1970s political movements and revolutionary changes in communication made these American styles international; as the art world itself became more and more international. American Lyrical Abstraction's European counterpart Neo-expressionism came to dominate the 1980s, and also developed as a response to American Pop Art and Minimalism and borrows heavily from American Abstract Expressionism.

Painters in America[edit]

This is a list of artists, whose work or a period or significant aspects of it, has been seen as lyrical abstraction, including those before the identification of the term or tendency in America in the 1960s.

See also[edit]

- Abstract expressionism

- Color field painting

- Hard-edge painting

- Post-painterly abstraction

- Tachisme

- COBRA (avant-garde movement)

- Formalism (art)

- Western painting

- History of painting

- Orphism (art)

- Nuagisme

References[edit]

- ^ Tate Collection - John Hoyland

- ^ a b Aldrich, Larry. Young Lyrical Painters, Art in America, v.57, n6, November–December 1969, pp.104–113.

- ^ [1] Thomas B. Hess on Larry Aldrich, Retrieved June 10, 2010

- ^ Arshile Gorky a Retrospective at the Tate Modern

- ^ Kemper Museum Retrieved June 5, 2010

- ^ interview with Richard Bellamy, 1963, Archives of American Art, retrieved February 1st, 2009

- ^ The Lyrical Flight, Paris 1945–1956, texts Patrick-Gilles Persin, Michel and Pierre Descargues Ragon, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris and Skira, Milan, 2006, 280 p. ISBN 88-7624-679-7.

- ^ The Archives of American Art, Smithsonian, Betty Parsons Gallery Papers, Reel 4087–4089: Exhibition Records, Reel 4108: Artists Files, last names A–B.

- ^ Flight lyric, Paris 1945–1956, texts Patrick-Gilles Persin, Michel and Pierre Descargues Ragon, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris and Skira, Milan, 2006, 280 p. ISBN 88-7624-679-7.

- ^ a b artnet retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s Expanding Boundaries: Lyrical Abstraction: Selections from the Permanent Collection, Boca Raton Museum of Art, retrieved June 17, 2009

- ^ NY Magazine, Sept. 11, 1972, Vol. 5, #37

- ^ 2002 Exhibition review, retrieved October 27, 2008 Archived July 9, 2012, at archive.today

- ^ Lyrical Abstraction: Color and Mood, Sheldon Museum of Art, exhibition review "New Exhibit goes big, bold" Lincoln Journal-Star, Sunday, May 30th, 1993

- ^ Ashton, Dore. Young Abstract Painters: Right On! Arts v. 44, n. 4, February, 1970, pp. 31–35.

- ^ Ratcliff, Carter. The New Informalists, Art News, v. 68, n. 8, December 1969, p.72.

- ^ University of Nebraska Lincoln, Sheldon Museum of Art, May 1993

- ^ Lyrical Abstraction, exhibition: May 25 through July 6, 1971, "Foreword by John I. H. Baur"

- ^ Lyrical Abstraction, exhibition: April 5 through June 7, 1970.

- ^ Lyrical Abstraction, exhibition: May 25 through July 6, 1971.

- ^ "Interview with John Seery 2010, Whitewall Magazine". Archived from the original on 2012-03-01. Retrieved 2010-05-26.

- ^ Lyrical Abstraction, exhibition: April 5 through June 7, 1970. Statement of the exhibition

- ^ Lyrical Abstraction, exhibition: May 25 through July 6, 1971, "Foreword by John I. H. Baur"

- ^ Robbins, Daniel. Larry Poons: Creation of the Complex Surface, Exhibition Catalogue, Salander/O'Reilly Galleries, p. 10, 1990.

- ^ Lyrical abstraction Aldrich Museum of Contemporary Art, 1970

- ^ Lyrical Abstraction Gift of the Larry Aldrich Foundation, 1971

- ^ a b c d e f Saatchi Retrieved May 27, 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g h [2] Archived 2010-07-03 at the Wayback Machine Santa Barbara Museum, retrieved June 2, 2010

- ^ a b c d Inc, Time (1970-05-01). "LIFE".

{{cite journal}}:|last1=has generic name (help); Cite journal requires|journal=(help) - ^ NY Magazine, 1969

- ^ David Bourdon, Life Magazine May 1970, Whats Up in Art, The Castelli Clan, David Whitney Gallery and Lyrical Abstraction, [3] Retrieved June 9, 2010

- ^ a b c d Glass House history chapter 1 Archived 2011-10-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ John Seery new work retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ a b Movers and Shakers, New York, "Leaving C&M", by Sarah Douglas, Art and Auction, March 2007, V.XXXNo7.

- ^ Martin, Ann Ray, and Howard Junker. The New Art: It's Way, Way Out, Newsweek 29 July 1968: pp.3,55–63.

- ^ "Jack Bush". The Art History Archive; Canadian Art. Retrieved December 9, 2008.

- ^ Livingston, Jane. The Art of Richard Diebenkorn. 1997-1998 Exhibition catalog. In The Art of Richard Diebenkorn, Whitney Museum of American Art. 56. ISBN 0-520-21257-6

- ^ NY Times obituary Richard Diebenkorn Lyrical Painter Dies at 71

- ^ a b tate.org.uk Archived 2012-01-11 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ Dorment, Richard. "Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective at Tate Modern, review", The Daily Telegraph, 8 February 2010. Retrieved May 24, 2010.

- ^ Art Daily retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ "L.A. Art Collector Caps Two Year Pursuit of Artist with Exhibition of New Work", ArtDaily. Retrieved 26 May 2010. "Lyrical Abstraction ... has been applied at times to the work of Arshile Gorky"

- ^ "Arshile Gorky: A Retrospective", Tate, February 9, 2010. Retrieved June 5, 2010.

- ^ Van Siclen, Bill. "Art scene by Bill Van Siclen: Part-time faculty with full-time talent" Archived 2011-06-22 at the Wayback Machine, The Providence Journal, July 10, 2003. Retrieved June 10, 2010.

- ^ NY Times obituary retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ Honolulu Academy of Art retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ Artists' estates: reputations in trust By Magda Salvesen, Diane Cousineau, p.69 Google books, retrieved May 27, 2010

- ^ Design Latitudes, Knoedler & Company retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j Color as Field retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ Art in Print Retrieved June 5, 2010

- ^ Frieze Magazine Retrieved May 27, 2010

- ^ a b Baker, Kenneth. Berggruen's gallery goes back into color fields, exhibition review

- ^ Philip Guston and a New Alphabet, Harvard Art Museums Retrieved June 5, 2010

- ^ Phillips collection retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ Saatchi Gallery retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ Kenneth Baker, SF Gate retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ artist biography retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ Michael Brenson, 1990, NY Times review retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ [Holland Kotter, 1997, NY Times review]retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ a b Lyrical abstraction movement retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ a b "L.A. Art Collector Caps Two Year Pursuit of Artist with Exhibition of New Work" on ArtDailyRetrieved May 28, 2010

- ^ Art Daily conversations with Lyrical Abstraction 1958-2009 Retrieved May 27, 2010

- ^ Art Gallery of Windsor retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ Big Color, MIT Retrieved May 27, 2010

- ^ Butler Institute of American Art catalog retrieved May 24, 2010

- ^ [4] Expanding Boundaries, Lyrical Abstraction at the Boca Raton Museum

- ^ interview with Richard Bellamy, 1963, Archives of American Art, retrieved May 27, 2010

Sources[edit]

- Landfield, Ronnie, Lyrical Abstraction, In The Late Sixties, 1993–95, and other writings – various published and unpublished essays, reviews, lectures, statements and brief descriptives at [5].

- Robbins, Daniel. Larry Poons: Creation of the Complex Surface, Exhibition Catalogue, Salander/O'Reilly Galleries, pp. 9–19, 1990.

- Zinsser, John. Larry Poons, an interview reprinted from Journal of Contemporary Art, Fall/Winter 1989, vol.2.2 pp. 28–38. Exhibition Catalogue, Salander/O'Reilly Galleries, pp. 20–24, 1990.

- Peter Schjeldahl. New Abstract Painting: A Variety of Feelings, Exhibition review, "Continuing Abstraction ", The Whitney Downtown Branch, 55 Water St. NYC. The New York Times, October 13, 1974.

- Carmean, E.A. Toward Color and Field, Exhibition Catalogue, Houston Museum of Fine Arts, 1971.

- Henning, Edward B. Color & Field, Art International May 1971: 46–50.

- Tucker, Marcia. The Structure of Color, New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC, 1971.

- Ratcliff, Carter. Painterly vs. Painted, Art News Annual XXXVII, Thomas B. Hess, and John Ashberry, eds.1971, pp..129–147.

- Stephen Prokopoff.[1] Two Generations of Color Painting, Exhibition Catalogue, Philadelphia Institute of Contemporary Art, 1971.

- Lyrical Abstraction, Exhibition Catalogue, Whitney Museum of American Art, NYC, 1971.

- Sharp, Willoughby. Points of View, A taped conversation with four painters," Ronnie Landfield, Brice Marden, Larry Poons and John Walker (painter), Arts, v. 45, n.3. December 1970, pp. 41–.

- Lyrical Abstraction, Exhibition Catalogue, the Aldrich Contemporary Art Museum, Ridgefield, Conn. 1970.

- Domingo, Willis. Color Abstractionism: A Survey of Recent American Painting, Arts, v. 45.n.3, December 1970, pp. 34–40.

- Channin, Richard. New Directions in Painterly Abstraction, Art International, Sept. 1970; pp. 62–64.

- Davis, Douglas. The New Color Painters, Newsweek 4 May 1970: pp. 84–85.

- Ashton, Dore. Young Abstract Painters: Right On! Arts v. 44, n. 4, February, 1970, pp. 31–35.

- Aldrich, Larry. Young Lyrical Painters, Art in America, v.57, n6, November–December 1969, pp. 104–113.

- Ratcliff, Carter. The New Informalists, Art News, v. 68, n. 8, December 1969, p. 72.

- Davis, Douglas M. This Is the Loose-Paint Generation, The National Observer 4 Aug. 1969: p. 20

- Martin, Ann Ray, and Howard Junker. The New Art: It's Way, Way Out, Newsweek 29 July 1968: pp. 3,55–63.

Bibliography[edit]

- L'Envolée Lyrique ("Lyrical Flight"), Paris 1945–1956, texts Patrick-Gilles Persin, Michel and Pierre Descargues Ragon, Musée du Luxembourg, Paris and Skira, Milan, 2006, 280 p. ( ISBN 88-7624-679-7 ).

- Gérard Xuriguera. Les Années 50, Arted, Paris, 1984.

- Dora Vallier. L'Art Abstrait, Livre de Poche, Paris, 1980.

- Michel Ragon et Michel Seuphor. L'art abstrait, (volume 4: 1945–1970), Maeght, Paris, 1974.

External links[edit]

- https://web.archive.org/web/20121020093645/http://www.abstract-art.com/abstraction/l5_wordings_fldr/l1_lyr_abst_proposal.html

- https://web.archive.org/web/20120915134250/http://www.abstract-art.com/

- http://www.artinsight.com/lyrical_abstraction.html

- http://www.nga.gov.au/International/Catalogue/Detail.cfm?IRN=36016&BioArtistIRN=18438&MnuID=SRCH&GalID=ALL (Seery)

- http://www.nga.gov.au/International/Catalogue/Detail.cfm?IRN=36943&BioArtistIRN=22094&MnuID=2&GalID=1 (Young)

- http://www.nga.gov.au/International/Catalogue/Detail.cfm?IRN=112933&BioArtistIRN=14089&MnuID=SRCH&GalID=1 (Budd)

- James Brooks: My whole tendency has been away from the fast moving line either violent or lyrical.. (James Brooks)

- Art Word of the Day!

- ^ "Stephen Prokopoff, 71, Curator With an Eye for Neglected Art (Published 2001)". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 2022-09-29.