Malvina Hoffman

Malvina Cornell Hoffman | |

|---|---|

Roger Parry, Malvina Hoffman, c. 1920, collection of the Smithsonian Photography Initiative. | |

| Born | June 15, 1885 New York City, US |

| Died | July 10, 1966 (aged 81) New York City, US |

| Education |

|

| Known for | Sculptures of dancers and "Hall of Man" at the Field Museum of Natural History |

| Notable work |

|

| Spouse | Samuel Bonarios Grimson (1924–1936) |

Malvina Cornell Hoffman (June 15, 1885 – July 10, 1966)[a] was an American sculptor and author, well known for her life-size bronze sculptures of people. She also worked in plaster and marble. Hoffman created portrait busts of working-class people and significant individuals. She was particularly known for her sculptures of dancers, such as Anna Pavlova.[1][6] Her sculpture series of culturally diverse people, entitled Hall of the Races of Mankind, was a popular permanent exhibition at the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago.[7] It was featured at the Century of Progress International Exposition at the Chicago World's Fair of 1933.[8]

She was commissioned to execute commemorative monuments and was awarded many prizes and honors, including a membership to the National Sculpture Society. In 1925, she was elected into the National Academy of Design as an Associate member and became a full Academician in 1931.[9] Many of her portraits of individuals are among the collection of the New York Historical Society. She maintained a salon, a social gathering of artistic and personal acquaintances, at her Sniffen Court studio for many years.[9]

She was highly skilled in foundry techniques, often casting her own works.[8] Hoffman published a definitive work on historical and technical aspects of bronze casting, Sculpture Inside and Out, in 1939.[8][9]

Early life and education[edit]

Malvina Hoffman was born in New York City, the fourth of six children of the concert pianist and composer, Richard Hoffman, and Fidelia Marshall (Lamson) Hoffman.[1][3] She was named after a maternal aunt, Malvina Helen (Lamson) Cornell, who would later survive the sinking of the RMS Titanic. Her mother, also a pianist, presided over her education at home until she was 10 years of age.[1][2] The Hoffman's regularly entertained artists and musicians in their home.[1] As a young girl, she met Swami Vivekananda when he lived and taught in New York City, and several of her later sculptures, like that of Sri Ramakrishna, are located at the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of New York.[10][b]

Hoffman attended Veltin School for Girls,[9] Chapin, and Brearley private schools.[1] While at Brearley, she took evening classes at the Woman's School for Applied Design and the Art Students League of New York.[1]

She studied painting with John White Alexander in 1906,[1][9] and also with Harper Pennington.[1] Hoffman developed her skill as an artist during her studies with George Grey Barnard, Herbert Adams, and Gutzon Borglum.[1][9] She worked as an assistant to sculptor Alexander Phimister Proctor at his MacDougal Street studio in Greenwich Village in 1907.[12] In 1908, Hoffman traveled to Paris with Katharine Rhoades and Marion H. Beckett and studied art there.[13]

In 1909 she made a bust of her father, her first finished sculpture, two weeks prior to his death. It was exhibited at the National Academy the following year.[2][9] Also in 1910, she won an honorable mention for a sculpture of her future husband, Samuel Grimson, at the Paris Salon.[3] Hoffman gravitated towards sculpture due to the artistic freedom she felt when creating a three-dimensional work of art.[2]

After her father's death in 1910, Hoffman moved to Europe with her mother.[14] They first visited London, where they attended the ballet of Alexander Glazunov's Autumn Bacchanale. Hoffman was inspired by the combination of motion and control exhibited by Mikhail Mordkin and Anna Pavlova.[1] Mother and daughter visited Italy before moving to Paris.[14] She worked as a studio assistant for Janet Scudder. During the nights she studied at Académie Colarossi. She studied with Emanuele Rosales[1] and after five unsuccessful attempts, she eventually was accepted as a student by Auguste Rodin.[2][15] She caught his attention when she quoted a poem that he attempted to remember by Alfred de Musset.[2] During their lessons, he advised her, "Do not be afraid of realism".[16] She made a trip to Manhattan in 1912 to dissect bodies at the College of Physicians and Surgeons at Columbia University.[1] From Rosales and Rodin, she learned about bronze casting, chasing, and finishing at foundries.[3] The Hoffman women lived in Paris until the outbreak of World War I in 1914.[1]

Career[edit]

Dancers[edit]

Hoffman became famous internationally for her sculptures of ballet dancers, such as Vaslav Nijinsky and Anna Pavlova, who often posed for her.[8][9] In 1911, she made Russian Dancers, which was exhibited that year at the National Academy and the following year at the Paris Salon. She made a plaster bust, the last work she made of Pavlova, in 1923.[9] Hoffman also created friezes and other works that captured the movements of dancers. In 1912, she made Bacchanale Russe. In 1917, a version of it won the National Academy's Julia A. Shaw Memorial Prize and the next year a large casting of the sculpture was on display in Paris at the Luxembourg Gardens.[9] She has been called "America's Rodin".[2]

World War I[edit]

Hoffman helped to organize, and was the American representative, for the French war charity, Appui aux Artistes that assisted needy artists. She also organized the American-Yugoslav relief fund for children.[1] While working for the Red Cross during World War I, Hoffman traveled to Serbia.[17] She made a larger-than-life-sized work of Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović, with whom she studied.[8]

Her sister, Helen, was on the board of the Red Cross, which sent clothing and medical supplies for the Serbian cause. Through her sister, she met Serbian Colonel Milan Pribićević in 1916, who inspired her when he came to the United States and delivered rousing speeches in which he asked Serbian immigrants to fight to save their homeland. Hoffman, who may have had a romantic relationship with the colonel, had an interest in "powerful, charismatic" people. She once said, "Hero worship formed a major part of my emotional life". He modeled for her sculpture of him entitled A Modern Crusader (1918).[19] His nephew said that it capture that "he was gaunt and weary. His eyes were deep sunk in their sockets ... Only his firm mouth and his powerful chin showed no trace of the inhuman punishment which his body and soul had received during half a decade of life in the trenches."[20] There are casts at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, Smithsonian American Art Museum, and Art Institute of Chicago.[17]

She also created the well known poster Serbia needs your help, based on the Miloje P. Igrutinović's photo of dead Serbian soldiers who had died of hunger and exhaustion on the Greek island of Vido. She made the soldier "live" on the poster and later, as a sort of an artistic installation, posted the soldier's head on the bronze statue of the Saint Francis of Assisi in front of the Mayo Clinic in Rochester, Minnesota.[21][22] She published her impressions about her visit in the chapter "Hunger in the Balkans" of her book Heads and Tales.[23]

The poster Serbia needs your help later circulated around the United States, including the library of a local politician in Phoenix, Arizona, or in the Navajo reservation. That was where the priest Janko Trbović found it. One reprint of the poster, after an intricate and extended search, was donated by the basketball player Vlade Divac.[23]

In 2018, an exhibition Who is Malvina Hoffman dedicated to her work was opened in Novi Sad, Serbia. It was part of the wider project "Serbia, war and posters" by the state government. The Hoffman exhibition, organized in cooperation with the US embassy in Belgrade, later toured the entire country.[21][22] Among other exhibits, Hoffman's drawings which she made when she visited Serbia in 1919 were also displayed.[23]

Interwar period[edit]

In 1919, she created a pedimental sculpture for Bush House in London. The same year, she was in Paris cataloging Rodin's works for the Musée Rodin.[9] In 1929, her first major exhibit was held at the Grand Central Art Galleries[9] with 105 works of art in various mediums.[8]

During the war, she met the American Red Cross worker John W. Frothingham and his Serbian wife Jelena Lozanić. As member of the American Red Cross, she and Lozanić continued to organize the relief for Serbia (now amalgamated into Yugoslavia) during the Interbellum, regularly giving lectures on orphaned Serbian children. She welcomed Croatian sculptor Ivan Meštrović, lending him her studio to work. In 1919, at the request of Herbert Hoover, director of American Relief Administration, Hoffman travelled to Serbia and Yugoslavia to visit US humanitarian missions throughout the state. That same year she visited the site of the 1389 Battle of Kosovo, as the second recorded American to do so, after John W. Frotingham (some even claim the second foreign visitor in general).[24]

After the war, she made the sculpture The Sacrifice, which was dedicated in 1923 at the Cathedral of St. John the Divine in New York. In it, the head of a 13th-century crusader lay on the lap of a draped woman. It is a memorial to the late Ambassador of France, Robert Bacon, and alumni of Harvard University who lost their lives during the war.[25] After the Memorial Church at Harvard University was completed in 1932, it was installed there.[9][26]

Hall of Man[edit]

In 1929, Hoffman received a telegram from Stanley Field, "Have proposition to make, do you care to consider it? Racial types to be modeled while traveling round the world."[15] The original proposal was to commission four or five artists to create painted plaster figures, as was common at the time, but Hoffman countered with a proposal to do the entire series by herself.[15] Her counter-proposal was accepted, and she was commissioned by the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago, Illinois to create anthropologically accurate sculptures of peoples of diverse nationalities and races.[15] Next, she determined to do the entire series in bronze, submitted two initial sculptures, and obtained approval to proceed.[15]

Her initial work on the series was done in her Manhattan studio, but then she moved to her studio in Paris, where she could refer to models from the Paris Colonial Exposition of 1931.[15] She then traveled around the world — including distant places like Africa, India, and Bali — in 1931 to 1932, creating busts and figures of people[9] and taking more than 2,000 photographs.[27]

To understand the submerged passion that burns in the human eye, to read the hieroglyphs of suffering etched in the lines of a human face ... to watch the gesture of a hand or listen for the false notes and the truth in a human voice, these are the mysteries that I found I must delve into and try to unravel when I made a portrait.

—Malvina Hoffman, explaining that her sculptures were more than an anthropological study.[8]

| External images | |

|---|---|

She completed more than 105 sculptures, predominantly in bronze, but also in marble and stone.[8] They included busts and full-length figures of individuals,[8] which were installed at the museum's Hall of Man in 1933. She documented her travels for the commission in the book, Heads and Tales.[9] It was a popular exhibit at the museum, but some critics considered it a purely anthropological study.[8]

During the 1960s, questions began to circulate about the exhibit. According to American Historical Review, "the sculptures in the 'Races of Mankind' had perpetuated an older typological approach by presenting 'race' in the form of literally static bronze figures depicting idealized racial 'types'".[28] The Hall of Man was deinstalled in 1969,[29] but some of the sculptures remained on display.[15]

In 2016, fifty recently conserved sculptures from the Mankind collection were re-installed at the museum in an exhibition called Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman.[30][31][32]

World War II[edit]

As she had during World War I, Hoffman served the Red Cross[17] and she raised money for the Red Cross and national defense during the war.[34] She again supported Serbia, which was again occupied by Germany. Jointly with the mayor of New York City, Fiorello La Guardia, she participated in the fund raising events of organized by Jelena Lozanić, and in sending of the relief to the occupied territory.[24]

In 1948, Hoffman created relief sculptures for the walls of the American World War II Memorial for the Epinal American Cemetery and Memorial in Vosges, France.[33] It is on the site of the Battle of the Bulge (1944). There are 5,255 American soldiers buried in the cemetery.[26]

Other[edit]

She depicted the evolution of medicine in a 13-panel bas relief for Boston's Joslin Diabetes Center. Hoffman made portrait sculptures, including those of John Muir, Wendell Willkie,[8] Ignacy Jan Paderewski, Henry Clay Frick, and Ivan Meštrović. Her works were exhibited often at the National Academy.[9] In 1965, she published Yesterday is Tomorrow.[9]

Among her awards[34] are the gold medal she won in 1924 from the National Academy, the gold medal of honor she won in 1962 for Mongolian Archer from the Allied of Artists of America, and the gold medal of honor that she won in 1964 from the National Sculpture Society.[35] She was awarded five honorary doctorates.[34][36] Her awards for public service include the French Legion of Honour and the Royal Order of St. Sava III of Yugoslavia.[34]

Her work is kept in the permanent collections of many museums worldwide, including the Metropolitan Museum of Art,[37] the Detroit Institute of Arts,[38] the Santa Barbara Museum of Art,[39] the Vero Beach Museum of Art,[40] the Harvard Art Museums,[41] the University of Michigan Museum of Art,[42] the Dallas Museum of Art,[43] the Smithsonian American Art Museum,[44] the Nasher Museum of Art,[45] and the Gilcrease Museum.[46]

Personal life[edit]

She was married to an Englishman, Samuel Bonarius Grimson, on June 4, 1924.[3][47] Grimson had been injured by mustard gas and phosgene during World War I, and his career as a concert violist was ended when his hands were crushed during an accident with a truck during the war. After the war, he collected antique paintings and instruments. He also invented a tube for a color television.[48] Grimson traveled with her during her search for authentic indigenous models for the anthropological series.[8] Hoffman and Grimson divorced in 1936; some speculated that it was due to an affair that she had with the ballerina Anna Pavlova.[47] Grimson later married Bettina Warburg, the daughter of Nina Loeb and Paul Warburg,[48][49] in 1942. She was 16 years his junior. Grimson died in 1955.[47][48]

Hoffman befriended painter Romaine Brooks, writer Gertrude Stein, and ballet dancer Anna Pavlova. She held costume parties and balls in her studio, which were reported in the city's society pages.[8] She often spent the summers in a Hartsdale cottage provided to her by Paul Warburg.[50]

On July 10, 1966, Malvina Cornell Hoffman died of a heart attack in her studio in Manhattan,[8] which had been purchased by the philanthropist Mary Williamson Averell and provided to Hoffman for a low-priced rent.[50]

Gallery[edit]

-

Mort Exquise (1913)

-

Boy and Panther Cub (1915)

-

Boy and Panther Cub, detail (1915)

-

Anglo-American Friendship, Bush House (1919)

-

L'Offrande (1920)

-

Pavlova (1926-1929)

-

Martinique Woman (1927)

-

Coal Miners Returning From Work (1939)

-

Berber Man (1948)

-

Rajputana Woman (1948)

-

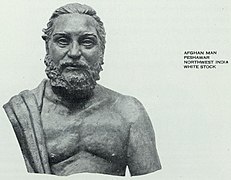

Afghan Man (1948)

-

Kashmiri in Meditation

Notes[edit]

- ^ Her date of birth is June 15, 1885 according to secondary sources[2][3] and the Social Security record of her death.[4] Her year of birth is also given as 1887.[5]

- ^ Others sculptures at the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center are Sarada Devi, Sri Ramakrishna, Swami Vivekananda and Swami Nikhilananda bust for Ramakrishna Vivekananda Center of New York[11]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Jules Heller; Nancy G. Heller (December 19, 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Taylor & Francis. p. 257. ISBN 978-1-135-63889-4.

- ^ a b c d e f g Carol Kort; Liz Sonneborn (May 14, 2014). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. Infobase Publishing. p. 95. ISBN 978-1-4381-0791-2.

- ^ a b c d e Barbara Sicherman; Carol Hurd Green (1980). Notable American Women: The Modern Period: a Biographical Dictionary. Harvard University Press. p. 343. ISBN 978-0-674-62733-8.

- ^ Malvina Hoffman, Issued in New York, 1952-1954, Social Security Death Index, Master File. Social Security Administration, July 1966

- ^ Marianne Kinkel (2011). Races of Mankind: The Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman. University of Illinois Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0-252-03624-8.

- ^ Essays on Women's Artistic and Cultural Contributions 1919–1939. 2009. p. 164.

- ^ Field Museum (January 1979). The Legacy of Malvina Hoffman. Vol. 50. Field Museum of Natural History Bulletin. Retrieved May 15, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n Carol Kort; Liz Sonneborn (May 14, 2014). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. Infobase Publishing. p. 96. ISBN 978-1-4381-0791-2.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q David Bernard Dearinger (2004). Paintings and Sculpture in the Collection of the National Academy of Design: 1826-1925. Hudson Hills. p. 276. ISBN 978-1-55595-029-3.

- ^ "Malvina Hoffman Sculptures at the Ramakrishna-Vivekananda Center of NY". ramakrishna.org. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ "Malvina Hoffman Sculpture of Sri Sarada Devi". ramakrishna.org. Retrieved March 7, 2016.

- ^ Sarah E. Boehme (Spring 2004). "Alexander Phimister Proctor and Gertrude Vanderbilt Whitney: Sculptor in Buckskin and American Princess". Points West magazine. Retrieved January 29, 2017 – via Buffalo Bill Center of the West.

- ^ Wardle, Marian (2005). American women modernists. [Provo (Utah)]: Brigham Young university Museum of Art. p. 223. ISBN 978-0813536842. Retrieved September 5, 2016.

- ^ a b Bailey, Brooke (1994). The Remarkable Lives of 100 Women Artists. Bob Adams Inc. pp. 78–79. ISBN 1-55850-360-9.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Malvina Hoffman". Field Museum of Natural History. November 8, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ "A Little Girl Who Remembered Vivekananda" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on July 11, 2015.

- ^ a b c Lauretta Dimmick; Donna J. Hassler (January 1, 1999). American Sculpture in the Metropolitan Museum of Art: A catalogue of works by artists born between 1865 and 1885. Metropolitan Museum of Art. p. 738. ISBN 978-0-87099-923-9.

- ^ "Modern Crusader | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved May 31, 2020.

- ^ Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, N.Y.) (January 1, 2003). Perspectives on American Sculpture Before 1925. Metropolitan Museum of Art. pp. 130–131. ISBN 978-1-58839-105-6.

- ^ "Modern Crusader". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved January 30, 2017.[permanent dead link]

- ^ a b S.K. (April 22, 2018). "Ko je Malvina Hofman" [Who is Malvina Hoffman]. Politika (in Serbian).

- ^ a b Miona Kovačević (May 21, 2017). ""Serbia needs your help" Kako je jedna Amerikanka oživela mrtvog srpskog vojnika" ["Serbia needs your help" How one American woman made a dead Serbian soldier alive] (in Serbian). Blic.

- ^ a b c Brane Kartalović (September 21, 2018). "Malvina Hofman – "Srbiji je potrebna tvoja pomoć"" [Malvina Hoffman – "Serbia needs your help"]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 12.

- ^ a b Tomislav Simonović (March 31, 2020). Како смо заборавили највећег српског добротвора из САД - Косовски дан Малвине Хофман, део 20 (изводи из књиге Џон В. Фротингхам, заборављени српски добротвор [How we forgot the greatest Serbian benefactor from USA - Kosovo Day of Malvina Hoffman (excerpts from the book John W. Frotingham, forgotten Serbian benefactor]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 23.

- ^ American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society (1922). Annual Report of the American Scenic and Historic Preservation Society to the Legislature of the State of New York. pp. 41–42.

- ^ a b Paula E. Calvin; Deborah A. Deacon (September 8, 2011). American Women Artists in Wartime, 1776-2010. McFarland. p. 84. ISBN 978-0-7864-8675-5.

- ^ "Photo Archives - Malvina Hoffman Collection". Field Museum of Natural History. February 18, 2011. Retrieved January 31, 2017.

- ^ Brattain, Michelle, "Race, Racism, and Antiracism: UNESCO and the Politics of Presenting Science to the Postwar Public". The American Historical Review 112.5 (2007): 40 pars. March 11, 2010.

- ^ Thomas W. Gaehtgens (March 5, 2013). Getty Research Journal. Getty Publications. pp. 123, 128. ISBN 978-1-60606-136-7.

- ^ "Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman - Field Museum". Field Museum. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Rothstein, Edward (March 22, 2016). "'Looking at Ourselves: Rethinking the Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman' Review". Wall Street Journal. Dow Jones & Company, Inc. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Edward Rothstein (March 23, 2016). "A Mold in Which to Cast a New Orthodoxy". Wall Street Journal. p. D5.

- ^ a b Lemay, Kate Clark (February 14, 2019). "How the U.S. Designed Overseas Cemeteries to Win the Cold War". What It Means to Be American.

- ^ a b c d Jules Heller; Nancy G. Heller (December 19, 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Taylor & Francis. p. 258. ISBN 978-1-135-63889-4.

- ^ "2 Receive Sculptor Society Medals". The New York Times. February 12, 1964. Retrieved April 23, 2023.

- ^ Carol Kort; Liz Sonneborn (May 14, 2014). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. Infobase Publishing. pp. 96–97. ISBN 978-1-4381-0791-2.

- ^ "Malvina Cornell Hoffman | Daboa". www.metmuseum.org. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Russian Dancers". www.dia.org. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Malvina HOFFMAN - Artists - eMuseum". collections.sbma.net. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Malvina Hoffman | Vero Beach Museum of Art". www.vbmuseum.org. January 21, 2018. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ Harvard. "From the Harvard Art Museums' collections La Javanese". harvardartmuseums.org. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Exchange: Small Study for the Column of Life". exchange.umma.umich.edu. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Untitled - DMA Collection Online". www.dma.org. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Malvina Hoffman | Smithsonian American Art Museum". americanart.si.edu. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "The Column of Life". Nasher Museum of Art at Duke University. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ "Sign Talk / Malvina Hoffman - Gilcrease Museum". collections.gilcrease.org. Retrieved January 15, 2021.

- ^ a b c Katharine Weber (June 2012). The Memory of All That: George Gershwin, Kay Swift, and My Family's Legacy of Infidelities. Crown/Archetype. pp. 166–167. ISBN 978-0-307-39589-4.

- ^ a b c Ron Chernow (November 15, 2016). The Warburgs: The Twentieth-Century Odyssey of a Remarkable Jewish Family. Knopf Doubleday Publishing Group. p. 605. ISBN 978-0-525-43183-1.

- ^ "Bettina Warburg Grimson; Psychiatrist, 90". New York Times. November 28, 1990.

- ^ a b Marianne Kinkel (2011). Races of Mankind: The Sculptures of Malvina Hoffman. University of Illinois Press. p. 212. ISBN 978-0-252-03624-8.

Further reading[edit]

- Connor, Janis, and Joel Rosenkranz, Rediscoveries in American Sculpture – Studio Works, 1893–1939, University of Texas Press, Austin 1989

- Field, Henry, The Races of Mankind, Sculptures by Malvina Hoffman, Anthropology Leaflet 30, Field Museum of Natural History, Chicago 1937

- Hoffman, Malvina, Heads and Tales. Charles Scribner's Sons, NY, NY 1936

- Hoffman, Malvina, Sculpture Inside and Out, Bonanza Books, NY, NY 1939

- Hoffman, Malvina, Yesterday Is Tomorrow, Crown Publishers, Inc. NY, NY 1965

- Kvaran, Einar Einarsson, Hunting Hoffman in the Field Museum, unpublished manuscript

- Nishiura, Elizabeth, American Battle Monuments – A Guide to Military Cemeteries and Monuments Maintained By the American Battle Monuments Commission, Omnigraphics, Inc, Detroit, Michigan 1989

- Papanikolas, Theresa and DeSoto Brown, Art Deco Hawai'i, Honolulu, Honolulu Museum of Art, 2014, ISBN 978-0-937426-89-0, p. 79

- Proske, Beatrice Gilman, Brookgreen Gardens Sculpture, Brookgreen Gardens, South Carolina, 1968

- Redman, Samuel J, Bone Rooms: From Scientific Racism to Human Prehistory in Museums. Cambridge: Harvard University Press. 2016.

External links[edit]

![]() Media related to Malvina Hoffman at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Malvina Hoffman at Wikimedia Commons

- Malvina Hoffman papers, 1897–1984. Getty Research Institute, Los Angeles. A nearly complete archive of letters, manuscripts, photographs, diaries, drawings, and films documents Malvina Hoffman's life and her career as a sculptor and writer.

- Photo of Malvina Hoffman by Clara Sipprell, at the Amon Carter Museum of American Art

- 20th-century American sculptors

- 1885 births

- 1966 deaths

- 20th-century American women writers

- Artists from New York City

- American modern sculptors

- National Sculpture Society members

- National Academy of Design members

- Brearley School alumni

- Chapin School (Manhattan) alumni

- Sculptors from New York (state)

- Writers from Manhattan

- American salon-holders

- Members of the American Academy of Arts and Letters

- 20th-century American women sculptors