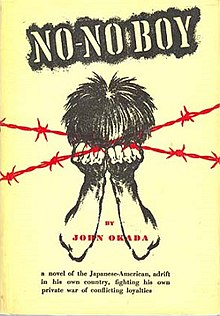

No-No Boy

First edition | |

| Author | John Okada |

|---|---|

| Country |

|

| Language | English |

| Genre | Historical fiction |

| Set in | Seattle, Washington (1946) |

| Publisher | Tuttle Publishing, University of Washington Press |

Publication date | 1957 |

| Media type | |

| Pages | 260 |

| ISBN | 0295955252 |

| OCLC | 2945142 |

No-No Boy is a 1957 novel, and the only novel published by the Japanese American writer John Okada. It tells the story of a Japanese-American in the aftermath of the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II. Set in Seattle, Washington, in 1946, the novel is written in the voice of an omniscient narrator who frequently blends into the voice of the protagonist.

Plot[edit]

After World War II, Ichiro Yamada, a Japanese American male and former student at the University of Washington, returns home in 1946 to a Japanese enclave in Seattle, Washington. He had spent two years in an American internment camp for Japanese Americans and two years in federal prison for refusing to fight for the U.S. in World War II. Now home, Ichiro struggles with his parents for embracing American customs and values, and he struggles to maintain a relationship with his brother, Taro. Also, Ichiro faces ostracism from the Japanese American community for refusing to join the U.S. military and fight Japan when many in his community did. Despite his struggles with his family and some members of the community, Ichiro maintains a friendship with Kenji, a Japanese American who fought for the U.S. and badly injured one of his legs. Kenji introduces Ichiro to Emi whose husband re-enlisted and remained in Germany after the war. Ichiro even manages to meet Mr. Carrick who interviews him for a draftsman position.

Perceived as disloyal to the U.S. but not fully Japanese, Ichiro struggles to find his path. Through Ichiro's story, Okada examines what it means to be American in a post-war society whose non-white communities are struggling to find their places.

Background[edit]

On 7 December 1941, the Imperial Japanese Navy launched a surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, a U.S. naval base near Honolulu, Hawaii. The following day, December 8, the United States declared war on Japan. Many Americans rushed to join the military. After Pearl Harbor, all citizens of Japanese ancestry had been classified 4-C, "enemy aliens", and denied entry into the armed forces. In spring 1942, the government began removing Japanese and Japanese American families from their homes and sending them to live in remote internment camps. As the war continued, the need for more soldiers increased.

In 1943, the War Department, along with the War Relocation Authority (WRA) created a bureaucratic means of testing the loyalty of all adults and teens in the WRA camps. The first form was aimed at draft-age Nisei males and the second form at all other residents. The last two questions, numbers 27 and 28 - where affirmative answers signaled unwavering loyalty to the U.S. - created confusion and resentment.

Question 27 asked if an individual would be willing to serve as a combat soldier, nurse, or in the Women's Army Auxiliary Corps. The internees had been advised that if accepted, they would serve in a segregated unit. Many felt this was offensive. Serving in the military meant leaving their families behind in the terrible conditions of the camps. Some resisted the draft, because their constitutional rights were being violated.

Question 28 was even more confusing. It was a two part question with one answer: "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States... and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government, power or organization?" Did an affirmative answer imply that they had once sworn allegiance to Japan? As a matter of principle some answered, "no" to both questions. For varied reasons, many respondents answered "no" to questions 27 and 28 and became known as "no-no boys".

The epithet "no-no boy" came from two questions on the Leave Clearance Application Form, also known as the loyalty questionnaire, administered to interned Japanese-Americans in 1943. Some young male internees answered "no" to one or both of these questions:

- "Are you willing to serve in the armed forces of the United States on combat duty wherever ordered?"

- "Will you swear unqualified allegiance to the United States of America and faithfully defend the United States from any or all attack by foreign or domestic forces, and forswear any form of allegiance or obedience to the Japanese emperor, to any other foreign government, power or organization?"

Both questions were confusing to many respondents. Regarding the first, some respondents thought that by answering yes, they were signing up for combat duty, while others, given their forced removal and incarceration, said no to resist the draft. Regarding the second, to many respondents, most of whom were American citizens, it implied that the respondent had already sworn allegiance to the Japanese emperor. They saw the second question as a trap, and rejected the premise by answering no. Afterwards, all who answered "no" to one or both questions, or who gave an affirmative answer but qualified it with statements like "I'll serve in the military after my family is freed", were sent to the Tule Lake Segregation Center.[1] Approximately 300 young men served time in federal prison for refusing to join the military from camp.[2]

The basic plot is not autobiographical. Okada, a Seattleite like his protagonist, served in the U.S. military himself. The novel was published in 1957 and remained obscure until much later. He died in 1971, at age 47.[3] A few years later, two young Asian-American men heard of Okada and his novel, and resolved to revive interest in it. With the co-operation of Okada's widow, they had it republished in 1976, with a second printing in 1977. Since then, it has become a staple of college assigned reading.

Content of the novel[edit]

Although a crucial part of the novel's setting is the injustice of the internment of Japanese-Americans, the novel is not a polemic about that event. Ichiro's turmoil during the novel also has much to do with rejecting his mother, whose personality and worldviews he despises and resents. His dissatisfaction with her is personal, going beyond her stance on the war. In chapter 1, it is disclosed that his mother and at least one of her women friends are loyal to Japan, refuse to believe the news that Japan lost the war, and are eagerly awaiting the arrival of Japanese warships in Seattle. They even refuse to accept the evidence of photos they have seen of the cities of Hiroshima and Nagasaki after the atomic bombings. These attitudes antagonize Ichiro and other Japanese Americans.

Publishing history and response[edit]

Following a string of rejections by American publishers, the Japanese publisher Charles E. Tuttle published an original run of 1,500 copies in 1957, which still had not sold out by the time Okada died in 1971. The initial response within the Japanese community was similar to that faced by the book's protagonist: ostracism for drawing attention to what was still perceived as disloyalty to the country and community.[4]

Found in a used book store by Jeff Chan in 1970, he and fellow Asian-American writers Frank Chin, Lawson Fusao Inada and Shawn Wong reached out to the Okada estate to first try and meet with John Okada, then when they discovered that he had died, to acquire the rights to reissue the book under their Combined Asian-American Resources Project (CARP) label in 1976. CARP sold out two printings of 3,000 copies each before transferring the rights in 1979 to University of Washington Press. University of Washington Press has since sold over 157,000 copies of the book (as of 2019), including its most recent edition in 2014.[5]

Penguin Random House published an edition of the novel in 2019, claiming that it was in the public domain and was never registered for copyright protection, sparking a controversy within the literary community for its failure to consult with the Okada estate and disregarding the struggle Okada and CARP had in attempting to publish the work.[6] It has been asserted that when No-No Boy was first published in 1957, the Copyright Act of 1909 applied, which granted book authors 28 years of protection unless renewed by the copyright holder, which CARP and the Okada estate failed to correctly apply.[7] Both the UW Press and the Penguin editions remain in circulation, although Penguin has since withdrawn any advertising in regards to its printing and has removed mention of the book from its webpage.[8]

2010 play adaptation[edit]

The novel was adapted as a stage play, also called No-No Boy, by Ken Narasaki. The play had its world premiere on 26 March 2010, at the Miles Memorial Playhouse in Santa Monica, California.[9]

References[edit]

- ^ Cherstin Lyon, "Loyalty questionnaire", Densho Encyclopedia, 19 March 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- ^ Eric Muller, "Draft resistance", Densho Encyclopedia, 10 June 2013. Retrieved 9 May 2014.

- Annie Nakao, "A Unique Tale of WWII Resistance: Japanese American Internees Refused Draft", San Francisco Chronicle, 26 October 2001. Retrieved 9 May 2014. - ^ La Force, Thessaly (4 November 2019), "The Story of the Great Japanese-American Novel", The New York Times

- ^ Schleitwiler, Vince (2019). "The legacy of 'No-No Boy'". University of Washington Magazine. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- Macdonald, Moira (16 June 2019). "'No-No Boy' went from unknown book to classic thanks to UW Press and Asian American writers. Now, it's at the center of a controversy". The Seattle Times. Retrieved 28 February 2020. - ^ Schleitwiler, Vince (18 November 2018). "The Bright Future and Long Shadow of John Okada's No-No Boy". Asian American Writers' Workshop. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ Chin, Frank (1976). In Search of John Okada: Afterword to 'No-No Boy'. Combined Asian American Resource Project. ISBN 9780295955254.

- ^ Fuchs, Chris (7 June 2019). "Penguin Classics edition of Japanese American novel 'No-No Boy' sparks copyright dispute". NBC News. Retrieved 28 February 2020.

- ^ No-No-Boy. OCLC. OCLC 881386427.

- ^ "World Premiere of No-No Boy announced", Los Angeles Daily News online