North Shore Congregation Israel

| North Shore Congregation Israel | |

|---|---|

North Shore Congregation | |

| Religion | |

| Affiliation | Reform Judaism |

| Ecclesiastical or organisational status | Synagogue |

| Status | Active |

| Location | |

| Location | 1185 Sheridan Road, Glencoe, Chicago, Illinois 60022 |

| Country | United States |

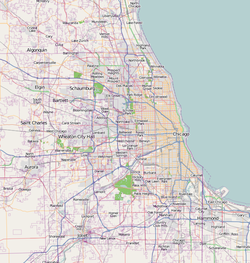

Location on the North Shore of Chicago, Illinois | |

| Geographic coordinates | 42°09′01″N 87°45′31″W / 42.1502°N 87.7585°W |

| Architecture | |

| Architect(s) | Minoru Yamasaki (1964)

|

| Type | Synagogue |

| Style | |

| Date established | 1920 (as a congregation) |

| Completed | 1964 |

| Site area | 19 acres (7.7 ha) |

| Website | |

| nsci | |

North Shore Congregation Israel is a Reform Jewish congregation and synagogue located at 1185 Sheridan Road in Glencoe, on the North Shore of Chicago, in Illinois, in the United States.

History[edit]

The congregation started in 1920 as the North Shore branch of Chicago's Sinai Congregation, and is the oldest Reform synagogue in the Chicago's North Shore suburbs. The decision to establish a separate congregation had been a subject of concerned discussion for a number of years, and was perceived as an important step in the evolution of the Jewish presence in the North Shore as a separate community.[1] The first full-time rabbi was Harvey Wessel in 1926.[2]

The congregation's 1964 building is located on a 19-acre (7.7 ha) lakefront parcel, formerly the location of a 1911 mansion that was designed by Chicago architect David Adler for his uncle, hat manufacturer Charles A. Stonehill, and was later owned by Syma Cohen Busiel, the co-founder of Lady Esther cosmetics, before it was sold to the congregation in 1961 for $500,000.[3][4]

The synagogue building was designed by the well-known, Detroit-based modernist architect Minoru Yamasaki. Yamasaki composed the building as a series of arching fan vaults. The voids between the concrete shells of the fan vaults are filled with colored glass above and clear glass at eye level. Yamasaki describes his design as "a confluence of daylight and solids."[5] The building has been described as representative of "a period of post-war modernism that was characterized by assertive architectural gestures that had the strength and integrity to stand alone, without applied artwork or Jewish iconography."[5] Architecture critic Samuel D. Gruber chose an image of the interior of Yamasaki's sanctuary for the cover of his book American Synagogues: A Century of Architecture and Jewish Community,[6] and has noted that this "dramatic, awe-inspiring space" was "hard to use by a congregation, so a smaller sanctuary was built in 1979. Together, the two connected buildings create a portrait of Jewish aspirations in the late-20th century."[7]

In celebration of the 2018 Illinois Bicentennial, the North Shore Congregation Israel Synagogue was selected as one of the Illinois 200 Great Places[8] by the American Institute of Architects Illinois component.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Ebner, Michael H. (1988). Creating Chicago's North Shore: A Suburban History. University of Chicago Press. pp. 226, 237. ISBN 978-0226182056. Excerpts available at Google Books.

- ^ Olitzky, Kerry; Raphael, Marc (1996). The American Synagogue: A Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook. Greenwood Press. p. 135.

- ^ Salny, Stephen M. (2001). The Country Houses of David Adler. W. W. Norton & Company. pp. 24–27. ISBN 978-0393730456. Excerpts available at Google Books.

- ^ "Glencoe Estate Is Party Setting: Famed Mansion to Be Razed". Chicago Tribune. August 27, 1961. p. 8:2. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ a b Stoltzman, Henry; Stoltzman, Daniel (2004). Synagogue Architecture in America; Path, Spirit, and Identity. Images Publishing. p. 193.

- ^ Smorol, Lorraine (September 15, 2004). "Temples of Swoon". Syracuse New Times. Archived from the original on April 2, 2015. Retrieved March 17, 2015 – via HighBeam Research.

- ^ "10 great places to share history of the Jewish faith". USA Today. September 30, 2005. Retrieved March 17, 2015.

- ^ Waldinger, Mike (January 30, 2018). "The proud history of architecture in Illinois". Springfield Business Journal. Retrieved January 30, 2018.

External links[edit]

- Official website

- Architectural tour at Archive.org

- "North Shore Congregation Israel Synagogue". Illinois Great Places.

- Milnarik, Elizabeth (2012). Esperdy, Gabrielle; Kingsley, Karen (eds.). "North Shore Congregation Israel, [Glencoe, Illinois]". SAH Archipedia. Charlottesville: Society of Architectural Historians and University of Virginia Press.

- 1920 establishments in Illinois

- 20th-century synagogues in the United States

- Jewish organizations established in 1920

- Minoru Yamasaki buildings

- Modernist architecture in Illinois

- Modernist synagogues

- Postmodern architecture in the United States

- Postmodern synagogues

- Reform synagogues in Illinois

- Synagogues completed in 1964

- Synagogues in Glencoe, Illinois