Perfluorononanoic acid

| |

| |

| Names | |

|---|---|

| IUPAC name

Heptadecafluorononanoic acid

| |

| Other names

perfluoro-n-nonanoic acid, PFNA, perfluorononanoate, C9 PFCA

| |

| Identifiers | |

3D model (JSmol)

|

|

| 1897287 | |

| ChEBI | |

| ChEMBL | |

| ChemSpider | |

| ECHA InfoCard | 100.006.184 |

| EC Number |

|

| 317302 | |

PubChem CID

|

|

| UNII | |

CompTox Dashboard (EPA)

|

|

| |

| |

| Properties | |

| C9HF17O2 | |

| Molar mass | 464.08 g/mol |

| Appearance | white crystalline powder |

| Melting point | 59 to 62 °C (138 to 144 °F; 332 to 335 K)[4] |

| Boiling point | 218 °C (424 °F; 491 K)[5] |

| 9.5 g/L[1] | |

| Solubility in other solvents | polar organic solvents |

| Acidity (pKa) | ~0[2][3] |

| Hazards | |

| Occupational safety and health (OHS/OSH): | |

Main hazards

|

Strong acid and suspected carcinogen |

| GHS labelling: | |

| |

| Danger | |

| H302, H318, H332, H351, H360, H362, H372 | |

| P201, P202, P260, P261, P263, P264, P270, P271, P280, P281, P301+P312, P304+P312, P304+P340, P305+P351+P338, P308+P313, P310, P312, P314, P330, P405, P501 | |

| Related compounds | |

Related compounds

|

Trifluoroacetic acid (TFA), Perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA), Perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS) |

Except where otherwise noted, data are given for materials in their standard state (at 25 °C [77 °F], 100 kPa).

| |

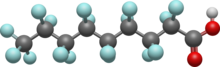

Perfluorononanoic acid, or PFNA, is a synthetic perfluorinated carboxylic acid and fluorosurfactant that is also an environmental contaminant found in people and wildlife along with PFOS and PFOA.

Chemistry and properties[edit]

In acidic form it is a highly reactive strong acid. In its conjugate base form as a salt it is stable and commonly ion paired with ammonium. In the commercial product Surflon S-111 (CAS 72968-3-88) it is the primary compound present by weight. PFNA is used as surfactant for the production of the fluoropolymer polyvinylidene fluoride.[6][7] It is produced mainly in Japan by the oxidation of a linear fluorotelomer olefin mixture containing F(CF2)8CH=CH2. It can also be synthesized by the carboxylation of F(CF2)8I. PFNA can form from the biodegradation of 8:2 fluorotelomer alcohol.[8] Additionally, it is considered a probable degradation product of many other compounds.[9]

PFNA is the largest perfluorinated carboxylic acid surfactant. Fluorocarbon derivatives with terminal carboxylates are only surfactants when they possess five to nine carbons.[10] Fluorosurfactants reduce the surface tension of water down to half of what hydrocarbon surfactants can by concentrating at the liquid-air interface due to the lipophobicity of fluorocarbons.[10][11] PFNA is very stable and is not known to degrade in the environment by oxidative processes because of the strength of the carbon–fluorine bond and the electronegativity of fluorine.

Environmental and health concerns[edit]

Like the eight-carbon PFOA, the nine-carbon PFNA is a developmental toxicant and an immune system toxicant.[12] However, longer chain perfluorinated carboxylic acids (PFCAs) are considered more bioaccumulative and toxic.[13] PFNA is an agonist of the nuclear receptors PPARα and PPARγ.[12] In the years between 1999–2000 and 2003–2004, the geometric mean of PFNA increased from 0.5 parts per billion to 1.0 parts per billion in the US population's blood serum.[14] and has also been found in human follicular fluid [15] In a cross-sectional study of 2003–2004 US samples, a higher (13.9 milligram per deciliter) total cholesterol level was observed in when the highest quartile was compared to the lowest.[16] Non-HDL cholesterol (or "bad cholesterol") levels were also higher in samples with more PFNA.

In bottlenose dolphins from Delaware Bay, PFNA was the perfluorinated carboxylic acid measured in the highest concentration in blood plasma; it was found in concentrations well over 100 parts per billion.[17] PFNA has been detected in polar bears in concentrations over 400 parts per billion.[18] PFNA was the perfluorinated chemical measured in the highest concentration in Russian Baikal seals.[19] However, PFOS is the perfluorinated compound that dominates in most wildlife biomonitoring samples.[20]

Drinking water regulations[edit]

In the United States there are no federal drinking water standards for any of the perfluorinated alkylated substances as of late 2020.[21] The U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) published a non-enforceable health advisory for PFOA in 2016. The agency's health advisory level for the combined concentrations of PFOA and PFOS is 70 parts per trillion (ppt).[22] [23]

In June 2020 the State of New Jersey published a drinking water standard for PFOA, the first state to do so. Public water systems in New Jersey are required to meet a maximum contaminant level (MCL) standard of 14 ppt. The state also set a PFOS standard at 13 ppt.[24] The state had set a standard for PFNA in September 2018, with an MCL of 13 ppt.[25][26]

In August 2020 the State of Michigan adopted drinking water standards for 5 previously unregulated PFAS compounds and lowered acceptable levels for 2 previously regulated compounds PFOS and PFOA to 16 ppt and 8 ppt respectively. PFNA has a MCL of 6 ppt.[27][28]

Food Regulation[edit]

In 2020, the European Food Safety Authority added PFNA in its revised safety threshold for PFAS that accumulate in the body. They set the threshold for a group of four PFAS of a tolerable weekly intake of 4.4 nanograms per kilogram of body weight per week.[29]

Product Restrictions[edit]

In 2020, a California bill was passed banning PFNA as an intentionally added ingredient from cosmetics.[30]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ "Safety (MSDS) data for perfluorononanoic acid". PTCL Safety web site. Archived from the original on 1 April 2009. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ Goss KU (July 2008). "The pKa values of PFOA and other highly fluorinated carboxylic acids". Environ. Sci. Technol. 42 (2): 456–458. Bibcode:2008EnST...42..456G. doi:10.1021/es702192c. PMID 18284146.

- ^ Rayne S, Forest K (June 2010). "Theoretical studies on the pKa values of perfluoroalkyl carboxylic acids". J. Mol. Struct. (Theochem). 949 (1–3): 60–69. doi:10.1016/j.theochem.2010.03.003.

- ^ "Perfluorononanoic acid 97%". Sigma-Aldrich. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ "Perfluorononanoic acid". ChemicalBook. Archived from the original on 13 June 2018. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ Prevedouros K, Cousins IT, Buck RC, Korzeniowski SH (January 2006). "Sources, fate and transport of perfluorocarboxylates". Environ Sci Technol. 40 (1): 32–44. Bibcode:2006EnST...40...32P. doi:10.1021/es0512475. PMID 16433330. Supporting Information (PDF).

- ^ PERFORCE — PERFLUORINATED ORGANIC COMPOUNDS IN THE EUROPEAN ENVIRONMENT (PDF). Institute for Biodiversity and Ecosystem Dynamics, Universiteit van Amsterdam. 2006-09-15. p. 18. Retrieved 2009-02-15.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Henderson WM, Smith MA (February 2007). "Perfluorooctanoic acid and perfluorononanoic acid in fetal and neonatal mice following in utero exposure to 8–2 fluorotelomer alcohol". Toxicol. Sci. 95 (2): 452–61. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfl162. PMID 17093205.

- ^ Lists of PFOS, PFAS, PFOA, PFCA, related compounds and chemicals that may degrade to PFCA (PDF). Environment Directorate-Joint Meeting of the Chemicals Committee and the Working Party on Chemicals, Pesticides, and Biotechnology. Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development. 2007-08-21. Retrieved 2008-09-19.

{{cite conference}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ a b Salager, Jean-Louis (2002). FIRP Booklet # 300-A: Surfactants-Types and Uses (PDF). Universidad de los Andes Laboratory of Formulation, Interfaces Rheology, and Processes. p. 44. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2020-07-31. Retrieved 2008-09-07.

- ^ "Fluorosurfactant — Structure / Function". Mason Chemical Company. Archived from the original on 5 July 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ a b Fang X, Zhang L, Feng Y, Zhao Y, Dai J (October 2008). "Immunotoxic effects of perfluorononanoic acid on BALB/c mice". Toxicol. Sci. 105 (2): 312–21. doi:10.1093/toxsci/kfn127. PMID 18583369.

- ^ Del Gobbo L, Tittlemier S, Diamond M, et al. (August 2008). "Cooking decreases observed perfluorinated compound concentrations in fish". Journal of Agricultural and Food Chemistry. 56 (16): 7551–9. doi:10.1021/jf800827r. PMID 18620413.

- ^ Calafat AM, Wong LY, Kuklenyik Z, Reidy JA, Needham LL (November 2007). "Polyfluoroalkyl chemicals in the U.S. population: data from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey (NHANES) 2003–2004 and comparisons with NHANES 1999–2000". Environ. Health Perspect. 115 (11): 1596–602. doi:10.1289/ehp.10598. PMC 2072821. PMID 18007991. Archived from the original on 2009-01-20. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ Bach, Cathrine Carlsen; Bech, Bodil Hammer; Nohr, Ellen Aagaard; Olsen, Jørn; Matthiesen, Niels Bjerregård; Bossi, Rossana; Uldbjerg, Niels; Bonefeld-Jørgensen, Eva Cecilie; Henriksen, Tine Brink (2015-10-01). "Serum perfluoroalkyl acids and time to pregnancy in nulliparous women". Environmental Research. 142: 535–541. Bibcode:2015ER....142..535B. doi:10.1016/j.envres.2015.08.007. PMID 26282225.

- ^ Nelson JW, Hatch EE, Webster, TF (2009). "Exposure to Polyfluoroalkyl Chemicals and Cholesterol, Body Weight, and Insulin Resistance in the General U.S. Population". Environ. Health Perspect. 118 (2): 197–202. doi:10.1289/ehp.0901165. PMC 2831917. PMID 20123614.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ Houde M, Wells RS, Fair PA, et al. (September 2005). "Polyfluoroalkyl compounds in free-ranging bottlenose dolphins (Tursiops truncatus) from the Gulf of Mexico and the Atlantic Ocean". Environ. Sci. Technol. 39 (17): 6591–8. Bibcode:2005EnST...39.6591H. doi:10.1021/es0506556. PMID 16190216.

- ^ Muir, Derek. Biomonitoring of perfluoroalkyl acids: An overview of the global and temporal trend data (PDF). Fluoros. Environment Canada - National Water Research Institute. Retrieved 2009-01-11.

- ^ "Water Pollution Continues At Famous Russian Lake". ScienceDaily. 25 March 2008. Retrieved 11 January 2009.

- ^ Houde M, Martin JW, Letcher RJ, Solomon KR, Muir DC (June 2006). "Biological monitoring of polyfluoroalkyl substances: A review". Environ. Sci. Technol. 40 (11): 3463–73. Bibcode:2006EnST...40.3463H. doi:10.1021/es052580b. PMID 16786681. Supporting Information (PDF).

- ^ "PFAS laws and Regulations". Washington, DC: United States Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). 2020-11-17.

- ^ "Drinking Water Health Advisories for PFOA and PFOS". EPA. 2020-12-09.

- ^ "Fact Sheet; PFOA & PFOS Drinking Water Health Advisories". November 2016. EPA 800-F-16-003.

- ^ "Adoption of ground water quality standards and maximum contaminant levels for perfluorooctanoic acid (PFOA) and perfluorooctanesulfonic acid (PFOS)". Trenton, NJ: New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection (NJDEP). 2020-06-01.

- ^ Fallon, Scott (2018-09-06). "New Jersey becomes first state to regulate dangerous chemical PFNA in drinking water". North Jersey Record. Woodland Park, NJ.

- ^ "Maximum Contaminant Levels (MCLs) for Perfluorononanoic Acid and 1,2,3-Trichloropropane; Private Well Testing for Arsenic, Gross Alpha Particle Activity, and Certain Synthetic Organic Compounds". NJDEP. 2018-09-04. 50 N.J.R. 1939(a).

- ^ Matheny, Keith (3 August 2020). "Michigan's drinking water standards for these chemicals now among toughest in nation". Detroit Free Press. Archived from the original on 31 January 2022. Retrieved 31 March 2022.

- ^ "New state drinking water standards pave way for expansion of Michigan's PFAS clean-up efforts". Michigan.gov. 3 August 2020. Archived from the original on 3 January 2022. Retrieved 5 April 2022.

- ^ "PFAS in food: EFSA assesses risks and sets tolerable intake". The European Food Safety Authority. September 17, 2020. Retrieved 17 October 2020.

- ^ "Assembly Bill No. 2762". State of California. September 30, 2020. Retrieved 10 October 2020.

External links[edit]

- Perfluorocarboxylic Acid Content in 116 Articles of Commerce PDF

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Polyfluorochemicals fact sheet

- Perfluorinated substances and their uses in Sweden

- Perfluoroalkylated substances, Aquatic environmental assessment

- Chain of Contamination: The Food Link, Perfluorinated Chemicals (PFCs) Incl. PFOS & PFOA