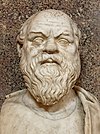

Socratic dialogue

| Part of a series on |

| Socrates |

|---|

|

| Eponymous concepts |

| Pupils |

| Related topics |

|

|

Socratic dialogue (Ancient Greek: Σωκρατικὸς λόγος) is a genre of literary prose developed in Greece at the turn of the fourth century BC. The earliest ones are preserved in the works of Plato and Xenophon and all involve Socrates as the protagonist. These dialogues, and subsequent ones in the genre, present a discussion of moral and philosophical problems between two or more individuals illustrating the application of the Socratic method. The dialogues may be either dramatic or narrative. While Socrates is often the main participant, his presence in the dialogue is not essential to the genre.

Platonic dialogues[edit]

Most of the Socratic dialogues referred to today are those of Plato. Platonic dialogues defined the literary genre subsequent philosophers used.

Plato wrote approximately 35 dialogues, in most of which Socrates is the main character. Strictly speaking, the term refers to works in which Socrates is a character. As a genre, however, other texts are included; Plato's Laws and Xenophon's Hiero are Socratic dialogues in which a wise man other than Socrates leads the discussion (the Athenian Stranger and Simonides, respectively). The protagonist of each dialogue, both in Plato's and Xenophon's work, usually is Socrates who by means of a kind of interrogation tries to find out more about the other person's understanding of moral issues. In the dialogues Socrates presents himself as a simple man who confesses that he has little knowledge. With this ironic approach he manages to confuse the other who boasts that he is an expert in the domain they discuss. The outcome of the dialogue is that Socrates demonstrates that the other person's views are inconsistent. In this way Socrates tries to show the way to real wisdom. One of his most famous statements in that regard is "The unexamined life is not worth living." This philosophical questioning is known as the Socratic method. In some dialogues Plato's main character is not Socrates but someone from outside of Athens. In Xenophon's Hiero a certain Simonides plays this role when Socrates is not the protagonist.

Generally, the works which are most often assigned to Plato's early years are all considered to be Socratic dialogues (written from 399 to 387). Many of his Middle dialogues (written from 387 to 361, after the establishment of his Academy), and later dialogues (written in the period between 361 and his death in 347) incorporate Socrates' character and are often included here as well.[1] However, this interpretation of the corpus is not universally accepted.[2] The time that Plato began to write his works and the date of composition of his last work are not known and what adds to the complexity is that even the ancient sources do not know the order of the works or the dialogues.[3]

The complete list of the thirty-five Platonic dialogues that have been traditionally identified as authentic, as given in Diogenes Laërtius,[4] is included below in alphabetical order. The authenticity of some of these dialogues has been questioned by some modern scholarship.[5]

- First Alcibiades

- Second Alcibiades

- Apology

- Charmides

- Clitophon

- Cratylus

- Critias

- Crito

- Epinomis

- Euthydemus

- Euthyphro

- Gorgias

- Hipparchus

- Hippias Major

- Hippias Minor

- Ion

- Laches

- Laws

- Lysis

- Menexenus

- Meno

- Minos

- Parmenides

- Protagoras

- Phaedo

- Phaedrus

- Philebus

- Republic

- Rival Lovers

- Sophist

- Statesman

- Symposium

- Theaetetus

- Theages

- Timaeus

Other ancient authors[edit]

Authors of extant dialogues[edit]

- Athenaeus, author of Deipnosophistae

- Cicero, author of several dialogues, including De re publica, De finibus bonorum et malorum, Tusculanae Disputationes, De Natura Deorum, De Divinatione, De fato, Academica, and the now-lost Hortensius.

- Xenophon, author of several dialogues, including Apology, Memorabilia, Oeconomicus, and Symposium

Authors whose dialogues are lost[edit]

- Simon the Shoemaker – According to Diogenes Laërtius he was the first author of a Socratic dialogue.[6]

- Alexamenus of Teos – According to a fragment of Aristotle, he was the first author of a Socratic dialogue, but we do not know anything else about him, whether Socrates appeared in his works, or how accurate Aristotle was in his antagonistic judgement about him.

- Aeschines of Sphettos

- Antisthenes

- Aristippus[7]

- Aristotle

- Phaedo of Elis

- Euclid of Megara

- Favorinus

Medieval and early modern dialogues[edit]

Socratic dialogue remained a popular format for expressing arguments and drawing literary portraits of those who espouse them. Some of these dialogues employ Socrates as a character, but most simply employ the philosophical style similar to Plato while substituting a different character to lead the discussion.

- Boethius

- Boethius' most famous book The Consolation of Philosophy is a Socratic dialogue in which Lady Philosophy interrogates Boethius.

- St. Augustine

- St. Augustine's Confessions has been called a Socratic dialogue between St. Augustine the author and St. Augustine the narrator.[8]

- Anselm of Canterbury

- Anselm's Cur Deus Homo is a Socratic dialogue between Anselm and a monk named Boso.

- Galileo Galilei

- Galilei's Dialogue Concerning the Two Chief World Systems compares the Copernican model of the universe with the Aristotelian.

- Matteo Ricci

- Ricci's The True Meaning of the Lord of Heaven (天主實義) is a Socratic dialogue between Ricci and a Chinese scholar, where Ricci argues that Christianity and Confucianism are not opposed to each other.

- Johann Joseph Fux

- Gradus ad Parnassum (1725), a non-Socratic dialogue on species counterpoint. The conversation is between Aloysius, who represents the compositional style of Palestrina, and his student, Josephus.

- George Berkeley

- Berkeley's Three Dialogues Between Hylas and Philonous is a Socratic dialogue between two university students named Philonous and Hylas, where Philonous tries to convince Hylas that idealism makes more sense than materialism.

- David Hume

- Hume's Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion is a Socratic dialogue in which three philosophers discuss arguments for the existence of God.

Modern dialogues[edit]

- Imre Lakatos

- Proofs and Refutations is a 1976 book on the logic of discovery and progress in mathematics. It is written as a series of Socratic dialogues between a group of students who debate the proof of the Euler characteristic for the polyhedron.

- Owen Barfield

- Barfield's Worlds is a dialogue in the Socratic tradition analyzing the problem of specialization in modern society and universities.[9]

- André Gide

- Gide's Corydon is a series of 4 Socratic dialogues which aims to convince the reader of the normality and utility of homosexuality in society.[10]

- Jane Jacobs

- Systems of Survival is a dialogue about two fundamental and distinct ethical systems (or syndromes as she calls them): that of the Guardian and that of Commerce. She argues that these supply direction for the conduct of human life within societies, and understanding the tension between them can help us with public policy and personal choices.[11]

- Peter Kreeft

- This academic philosopher has published a series of Socratic dialogues in which Socrates questions famous thinkers from the distant and near past. The first of the series was Between Heaven and Hell, a dialogue between C. S. Lewis, Aldous Huxley, and John F. Kennedy.[12] He also authored a book of Socratic logic.[13]

- Keith Buhler

- Buhler is an academic philosopher who published a Socratic dialogue in which Seraphim Rose plays the socratic questioner. He dialogues with a group of theology students on the Protestant doctrine of Sola Scriptura.[14]

- Gerd Achenbach and philosophical counseling

- Achenbach has refreshed the socratic tradition with his own blend of philosophical counseling, as has Michel Weber with his Chromatiques Center in Belgium.

- Ian Thomas Malone

- Malone has published a series of contemporary Socratic dialogues titled Five College Dialogues.[15] Five College Dialogues is intended to be a comedic resource for college students with a graduate student named “George Tecce” taking the role of Socrates.

- Robin Skynner and John Cleese

- In the 1980s and 1990s a British psychologist and the well-known comedian collaborated on two books, Families and How to Survive Them (1984) and Life and How to Survive It (1993), in which they take the Socratic dialogue approach to questions of families and life.[16][17]

- David Lewis and Stephanie Lewis

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Plato & Socrates, The Relationship Between Socrates and Plato, www.umkc.edu

- ^ Smith, Nicholas; Brickhouse, Thomas (2002). The Trial and Execution of Socrates : Sources and Controversies. New York: Oxford University press. p. 24. ISBN 9780195119800.

- ^ Fine, Gail (2011). The Oxford handbook of Plato. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 76, 77. ISBN 978-0199769193.

- ^ "Diogenes Laertius, Lives of Eminent Philosophers, Book III, Plato (427–347 B.C.)". www.perseus.tufts.edu.

- ^ Pangle, Thomas L. (1987). The Roots of Political Philosophy: Ten Forgotten Socratic Dialogues. Ithaca: Cornell University Press. pp. 1–20. ISBN 0801419867.

- ^ Diogenes Laërtius, Lives and Opinions of Eminent Philosophers, ii.123

- ^ Diogenes Laertius Lives of the Eminent Philosophers Book II Chapter 8 Section 83 http://www.perseus.tufts.edu/hopper/text?doc=Perseus%3Atext%3A1999.01.0258%3Abook%3D2%3Achapter%3D8

- ^ McMahon, Robert. "Augustine's Confessions and Voegelin's Philosophy". First Things. Archived from the original on 22 March 2014. Retrieved 5 December 2012.

- ^ Barfield, Owen. Worlds Apart.

- ^ Gide, Andre (1950). Corydon.

- ^ Mulhern, Francis J. (1995). "Review of Systems of Survival: A Dialogue on the Moral Foundations of Commerce and Politics". Journal of Marketing. 59 (1): 110–112. doi:10.2307/1252020. ISSN 0022-2429. JSTOR 1252020.

- ^ Kreeft, Peter. Between Heaven and Hell.

- ^ Kreeft, Peter. Socratic Logic: A Logic Text using Socratic Method, Platonic Questions, and Aristotelian Principles.

- ^ Buhler, Keith (10 June 2012). Sola Scriptura: A Dialogue. CreateSpace Independent Publishing. ISBN 978-1475270860.

- ^ Malone, Ian Thomas (25 August 2014). Five College Dialogues. ISBN 978-0692281451.

- ^ Sullivan, Jane (2 November 2018). "Turning Pages: the Literary Life of Monty Python". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 6 May 2019.

- ^ Skynner, Robin. "Life and how to survive it". RSA Journal Vol. 141, No. 5440 (June 1993), pp. 461–471

- ^ Lewis, David K. '[1]'. Australasian Journal of Philosophy, 48(2). (1970).

References[edit]

- Jowett, B. (1892). The Dialogues of Plato translated into English with Analyses and Introductions by B. Jowett, M.A. in Five Volumes. 3rd ed. revised and corrected. (Oxford University Press), via Liberty Fund