Rain gutter

A rain gutter, eavestrough, eaves-shoot or surface water collection channel is a component of a water discharge system for a building.[1] It is necessary to prevent water dripping or flowing off roofs in an uncontrolled manner for several reasons: to prevent it damaging the walls, drenching persons standing below or entering the building, and to direct the water to a suitable disposal site where it will not damage the foundations of the building. In the case of a flat roof, removal of water is essential to prevent water ingress and to prevent a build-up of excessive weight.

Water from a pitched roof flows down into a valley gutter, a parapet gutter or an eaves gutter. An eaves gutter is also known as an eavestrough (especially in Canada), spouting in New Zealand, rhone (Scotland),[2] eaves-shoot (Ireland) eaves channel, dripster, guttering, rainspouting or simply as a gutter.[3] The word gutter derives from Latin gutta (noun), meaning "a droplet".[4]

Guttering in its earliest form consisted of lined wooden or stone troughs. Lead was a popular liner and is still used in pitched valley gutters. Many materials have been used to make guttering: cast iron, asbestos cement, UPVC (PVCu), cast and extruded aluminium, galvanized steel, wood, copper, zinc, and bamboo.

Description[edit]

Gutters prevent water ingress into the fabric of the building by channelling the rainwater away from the exterior of the walls and their foundations. [5] Water running down the walls causes dampness in the affected rooms and provides a favourable environment for growth of mould, and wet rot in timber.[citation needed]

A rain gutter may be a:

- Roof integral trough along the lower edge of the roof slope which is fashioned from the roof covering and flashing materials.

- Discrete trough of metal, or other material that is suspended beyond the roof edge and below the projected slope of the roof.

- Wall integral structure beneath the roof edge, traditionally constructed of masonry, fashioned as the crowning element of a wall.[6]

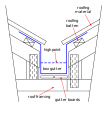

A roof must be designed with a suitable fall to allow the rainwater to discharge. The water drains into a gutter that is fed into a downpipe. A flat roof should have a watertight surface with a minimum finished fall of 1 in 80. They can drain internally or to an eaves gutter, which has a minimum 1 in 360 fall towards the downpipe. [7] The pitch of a pitched roof is determined by the construction material of the covering. For slate this will be at 25%, for machine made tiles it will be 35%. Water falls towards a parapet gutter, a valley gutter or an eaves gutter. [8] When two pitched roofs meet at an angle, they also form a pitched valley gutter: the join is sealed with valley flashing. Parapet gutters and valley gutters discharge into internal rainwater pipes or directly into external down pipes at the end of the run. [8]

-

A parapet gutter at the base of a sloping roof and a parapet wall, outflowing to a downpipe

-

A simpler parapet gutter.

-

A valley gutter between two parallel roof surfaces.

The capacity of the gutter is a significant design consideration. The area of the roof is calculated (metres) and this is multiplied by rainfall (litres/sec/metres²) which is assumed to be 0.0208. This gives a required discharge outfall capacity. (litres/sec) .[9] Rainfall intensity, the amount of water likely to generated in a two-minute rainstorm is more important than average rainfall, the British Standards Institute[10] notes that an indicative storm in Essex, (annual rainfall 500mm per annum) delivers 0.022 L/s/m²- while one in Cumbria (annual rainfall 1800mm per annum) delivers 0.014 L/s/m².[11]

Eaves gutters can be made from a variety of materials such as cast iron, lead, zinc, galvanised steel, painted steel, copper, painted aluminium, PVC (and other plastics) and occasionally from concrete, stone, and wood.[12]

Water collected by a rain gutter is fed, usually via a downpipe (also called a leader or conductor),[13] from the roof edge to the base of the building where it is either discharged or collected.[14] The down pipe can terminate in a shoe and discharge directly onto the surface, but using modern construction techniques would be connected through an inspection chamber to a drain that led to a surface water drain or soakaway. Alternatively it would connect via a gulley (u-bend) with 50mm water seal to a combined drain.[15] Water from rain gutters may be harvested in a rain barrel or a cistern.[16]

Rain gutters can be equipped with gutter screens, micro mesh screens, louvers or solid hoods to allow water from the roof to flow through, while reducing passage of roof debris into the gutter.[17]

Clogged gutters can also cause water ingress into the building as the water backs up. Clogged gutters can also lead to stagnant water build up which in some climates allows mosquitoes to breed.[18]

History[edit]

The Romans brought rainwater systems to Britain. The technology was subsequently lost, but was re-introduced by the Normans. The White Tower, at the Tower of London had external gutters. In March 1240 the Keeper of the Works at the Tower of London was ordered by King Henry "to have the Great Tower whitened both inside and out". This was according to the fashion at the time. Later that year the king wrote to the Keeper, commanding that the White Tower's lead guttering should be extended with the effect that "the wall of the tower ... newly whitened, may be in no danger of perishing or falling outwards through the trickling of the rain".[19]

In Saxon times, the thanes erected buildings with large overhanging roofs to throw the water clear of the walls in the same way that occurs in thatched cottages. The cathedral builder used lead parapet gutters, with elaborate gargoyles for the same purpose. With the dissolution of the monasteries- those buildings were recycled and there was plenty of lead that could be used for secular building. The yeoman would use wooden gutters or lead lined wooden gutters.

When The Crystal Palace was designed in 1851 by Joseph Paxton with its innovative ridge-and-furrow roof, the rafters that spanned the space between the roof girders of the glass roof also served as the gutters. The wooden Paxton gutters had a deep semi-circular channel to remove the rainwater and grooves at the side to handle the condensation. They were under trussed with an iron plate and had preformed notches for the glazing bars: they drained into a wooden box gutter that drained into and through structural cast iron columns.[20]

The industrial revolution introduced new methods of casting-iron and the railways brought a method of distributing the heavy cast-iron items to building sites. The relocation into the cities created a demand for housing that needed to be compact. Dryer houses controlled asthma, bronchitis, emphysema as well as pneumonia. In 1849 Joseph Bazalgette proposed a sewerage system for London, that prevented run-off being channelled into the Thames. By the 1870s all houses were constructed with cast iron gutters and down pipes. The Victorian gutter was an ogee, 115 mm in width, that was fitted directly to the fascia boards eliminating the need for brackets. Square and half-round profiles were also available. For a brief period after the first world war, asbestos-cement guttering became popular due to it being maintenance free: the disadvantages however ensured this was a short period: it was more bulky and fractured on impact. [21]

Types[edit]

Cast iron[edit]

Cast iron gutters were introduced in the late 18th century as an alternative to lead. Cast iron enabled eaves gutters to be mass-produced: they were rigid and non-porous while lead could only be used as a liner within timber gutters. Installation was a single process and didn't require heat.[22] They could be attached directly to the fascia board. Cast iron gutters are still specified for restoration work in conservation areas, but are usually replaced with cast aluminium made to the same profile. Extruded aluminium gutters can be made to a variety of profiles from a roll of aluminium sheet on site in lengths of up to 30 m. They feature internal brackets at 400 mm spacing.[23]

UPVC[edit]

In UK domestic architecture, guttering is often made from UPVC sections. The first PVC pipes were introduced in the 1930s for use in sanitary drainage systems. Polyethylene was developed in 1933. The first pressurised plastic drinking water pipes were installed in the Netherlands in the 1950s. During the 1960s rain water pipes, guttering and down pipes using plastic materials were introduced followed by PVC soil systems which became viable with the introduction of ring seals. A British Standard was launched for soil systems, local authorities started to specify PVC systems. By 1970 plastic rainwater systems accounted for over 60% of new installations.[citation needed] A European Standard EN607 has existed since 2004.[citation needed]

-

A collector with 112 mm gutter, draining into 68 mm downpipe

-

Available gutter fittings

-

Available pipe and gutter fittings

-

Fitting a gutter to a 45° connector

It is easy to install, economical, lightweight requires minimum maintenance and has a life expectancy of 50 years. The material has a disadvantageous coefficient of thermal expansion 0.06 mm/m°C, so design allowances have to be made. A 4-metre gutter, enduring a −5 °C to 25 °C temperature range will need space to expand, 30 × 4 × 0.06 = 7.2 mm within its end stops.[24] As a rule of thumb a 4-inch (100 mm) gutter with a single 68-millimetre (2.7 in) downpipe will drain a 600-square-foot (56 m2) roof.[25]

Stainless steel[edit]

High quality stainless steel guttering systems are available for homes and commercial projects. The advantages of stainless steel are durability, corrosion-resistance, ease of cleaning, and superior aesthetics. Compared with concrete or wood, a stainless steel gutter will undergo non-negligible cycles of thermal expansion and contraction as the temperature changes; if allowance for this movement is not made during installation, there will be a potential for deformation of the gutter, which may lead to improper drainage of the gutter system.

Seamless gutters[edit]

Seamless gutters have the advantage of being produced on site with a portable roll forming machine to match the specifications of the structure and are generally installed by experienced tradesman. Seamless gutter is .027" thick and if properly installed will last 30+ years.[citation needed]

Zinc[edit]

In commercial and domestic architecture, guttering is often made from zinc coated mild steel for corrosion resistance. Metal gutters with bead stiffened fronts is governed in the UK by BS EN612:2005.

Aluminium[edit]

Aluminium gutters offer good corrosion resistance, are lightweight, and are easy to install. Additionally, aluminium gutters come in a variety of finishes and styles that complement any home.[26]

-

Aluminium gutters in Moscow

Finlock gutters[edit]

Finlock gutters, a proprietary name[27] for concrete gutters, can be employed on a large range of buildings. There were used on domestic properties in the 1950s and 1960s, as a replacement for cast iron gutters when there was a shortage of steel and surplus of concrete. [citation needed] They were discredited after differential movement was found to open joints and allow damp to penetrate, but can be fitted with an aluminium and bitumastic liner.[28] Finlock concrete gutter units are made up of two troughs – one is the visible gutter and the other sits across the cavity wall. The blocks which can range from 8 to 12 inches (200 to 300 mm) can be joined using reinforcing rods and concrete, to form lintels for doors and windows.[28]

Vernacular buildings[edit]

Guttering can be made from any locally available material such as stone or wood. Porous materials may be lined with pitch or bitumen.

-

Wooden gutter at an open air museum

-

Wood used on a stone building

-

Stone gutter in Burgundy

-

Stone gutters in Slovenia

Shapes[edit]

Today in Western construction we use mainly three types of gutter - K-Style, round, and square. In days past there were 12 gutter shapes/styles. K-Style gets its name from its letter designation being the eleventh out of the twelve.

Gutter guards[edit]

Gutter guards (also called gutter covers, gutter protection or leaf guards) are primarily aimed at preventing damage caused from clogged gutters and reducing the need for regular gutter cleaning. They are a common add-on or included as an option for custom-built homes.

Types of gutter guards[edit]

Brush gutter guards resemble pipe cleaners and are easy to install. They prevent large debris from clogging gutters, but are less effective at reducing smaller debris.

Foam gutter guards are also easy to install. They fit into gutters, so they prevent large objects from obstructing waterflow, but they do not prevent algae and plant growth. A negative feature of foam type filters is that the pores quickly get clogged and thus need replacement due to not allowing water to pass through.

Reverse curve or surface tension guards reduce clogged gutters by narrowing the opening of the gutters. Many find them to be unattractive and difficult to maintain.

Screen gutter guards are among the most common and most effective. They can be snapped on or mounted, made of metal or plastic. Micromesh gutter guards provide the most protection from small and large debris.[29]

PVC type gutter guards are a less costly option, however, they tend to quickly become brittle due to sun exposure.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Chudley 1988, p. 476.

- ^ Collins English Dictionary. 1979.

- ^ Sturgis, Russell (1901). A Dictionary of Architecture and Building: Biographical, Historical, and Descriptive. The Macmillan Company.

- ^ Simpson (1963). New Compact Latin dictionary. Cassell.

- ^ Maskrey 2012, p. 461.

- ^ Sturgis' Illustrated Dictionary of Architecture and Building: An Unabridged Reprint of the 1901-2 Edition, Vol. II: F-N, p.340, ISBN 0-486-26026-7

- ^ Chudley 1988, p. 479.

- ^ a b Chudley 1988, pp. 476–7.

- ^ Maskrey 2012, p. 465.

- ^ BS EN 2056-3:2000

- ^ Maskrey 2012, p. 462.

- ^ Hardy, Benjamin (9 July 2013). "Gutters 101". Bob Vila. Retrieved 21 August 2014.

- ^ "Architectural Graphic Standards," First Edition, 1932, ISBN 0-471-51940-5, p. 77, 'Parts of a gutter' illustration

- ^ Ching, Francis D. K. (1995). A Visual Dictionary of Architecture. Van Nostrand Reinhold Company. p. 209. ISBN 0-442-02462-2.

- ^ Chudley 1988, p. 480.

- ^ "Rainwater Harvesting". Texas A&M AgriLife Extension. Texas A&M. Retrieved 29 June 2016.

- ^ Zhu, Qiang (2015). Rainwater Harvesting for Agriculture and Water Supply. Springer. p. 264. ISBN 978-9812879646.

- ^ "Mosquitoes and West Nile Virus in Delaware", dema.delaware.gov

- ^ Impey & Parnell 2000, pp. 25–27

- ^ Berlyn, Peter; Fowler, Charles (1851). The Crystal palace, its architectural history and constructive marvels. London, J. Gilbert. pp. 40–50. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Hall 1982, p. 422.

- ^ Trace, Paul. "A Cast Iron Solution". www.buildingconservation.com. Retrieved 27 December 2016.

- ^ Maskrey 2012, p. 427.

- ^ Maskrey 2012, p. 467.

- ^ Hall 1982, p. 423.

- ^ Ernestopro.com. "How to choose the best aluminum gutters".

- ^ Glover, Peter (2009). Building surveys (7th ed.). Amsterdam: Elsevier/Butterworth-Heinemann. p. 323. ISBN 978-1856176064.

- ^ a b Santo, Philip (2016). Inspections and Reports on Dwellings: Inspecting (Revised ed.). Taylor & Francis. p. 144. ISBN 978-1136021305.

- ^ Clark, Amara. "Gutter Screens – Fact or Fiction?". NED Stevens. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- Bibliography

- Chudley, R. (1988). Building construction handbook. London: Heinemann. ISBN 0434902365.

- Impey, Edward; Parnell, Geoffrey (2000), The Tower of London: The Official Illustrated History, Merrell Publishers in association with Historic Royal Palaces, ISBN 1-85894-106-7

- Maskrey, Michael B (2012). Level 2 NVQ diploma in plumbing and heating. London: City & Guilds. ISBN 9780851932095.

- Hall, E (1982). The New home owner manual. London: Hamlyn. ISBN 0600349918.