Ronald Reagan and AIDS

| ||

|---|---|---|

|

Personal life 33rd Governor of California

40th President of the United States Legacy |

||

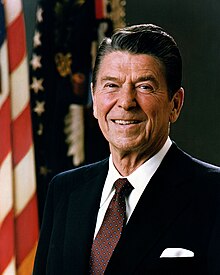

Ronald Reagan, the 40th President of the United States, oversaw the United States response to the emergence of the HIV/AIDS crisis during the 1980s. His actions, or lack thereof, have long been a source of controversy and have been widely criticized by LGBT and AIDS advocacy organizations.

AIDS was first medically recognized in 1981, in New York and California, and the term AIDS (acquired immunodeficiency syndrome) was created in 1982 to describe the disease. Lester Kinsolving, a reporter in the White House press pool, attempted to ask many early questions on AIDS, but his questions were not taken seriously. The 1985 illness and death of Rock Hudson marked a major turning point in how the American public viewed AIDS, with major policy shifts and funding increases coming in the wake of his death. Reagan did not publicly acknowledge AIDS until 1985 and did not give an address on it until 1987.

Reports on AIDS from Surgeon General C. Everett Koop in 1986 and James D. Watkins in 1988 were provided to the Reagan administration and offered information about AIDS and policy suggestions on how to limit its spread. However, the administration largely disregarded the recommendations in the reports. Towards the end of his presidency in 1988, Reagan took some steps to implement policies to stop the spread of AIDS such as notifications to those at risk of infection and barring federal discrimination against civilian employees with AIDS, though these actions have been criticized as not wide enough in their scope and too late in the crisis to prevent the deaths of tens of thousands of Americans.

As gay men, transgender women, and LGBT people in general were disproportionately afflicted with AIDS, some critics have suggested that Reagan's lack of action was motivated by homophobia. A belief among Christian conservatives at the time, including those in the White House and activists close to it, held that AIDS was a "gay plague" and any response to it should emphasize homosexuality as a moral failing, though there is little consensus on to what extent Reagan himself took to these views. Reagan's response to AIDS is generally viewed negatively by LGBT and AIDS activists, as well as epidemiologists. Criticism of Reagan's AIDS policies led to the creation of art condemning the government's inaction such as The Normal Heart, as well as invigorating a new wave of the gay rights movement.

Background[edit]

HIV/AIDS[edit]

Acquired immunodeficiency syndrome (AIDS) is a disease characterized by a greatly weakened or destroyed immune system, caused by HIV (human immunodeficiency virus), which attacks the body's components of the immune system. AIDS was first identified in mid-1981, as doctors in Los Angeles and New York City noticed a series of clusters of unusual infections, specifically Kaposi’s sarcoma and Pneumocystis pneumonia, in sexually active gay men, diseases which are normally only found in immunocompromised patients.[1] The disease was initially known as GRID (gay-related immune deficiency), and for a short period as the "4H disease" for "Homosexuals, Heroin addicts, Hemophiliacs and Haitians" as the predominately affected groups. However, as HIV has the ability to infect any person, AIDS had taken over as the term of choice by mid-1982.[2]

HIV was first identified as the cause of AIDS and isolated in parallel by researchers Luc Montagnier in France and Robert Gallo in the United States in 1983 and 1984.[3] Without treatment, HIV is inevitably fatal,[4] with a life expectancy for infected persons of 7 years.[5] The first treatment for HIV/AIDS, AZT, was not approved until 1987.[6] AIDS disproportionately affected, and continues to affect, members of the LGBT community, with gay men and transgender women being the most at risk.[7]

Ronald Reagan[edit]

Pre-presidential views on homosexuality[edit]

Ronald Reagan was a successful actor in the 1940s and 50s, and entered politics in 1966 to run for the seat of Governor of California, a position which he won and subsequently served in from 2 January 1967 to 6 January 1975. In 1967, while Reagan was in his first year in office as Governor, two close advisors of Reagan, Richard Quinn and Phil Battaglia (his chief of staff), were outed as gay in an article by Jack Anderson. Reagan had campaigned on ending "moral decline", and as many in this period viewed consorting with homosexual men as counter to this goal, Reagan chose to fire the men rather than face political backlash.[8][9][10] However, Reagan was reportedly privately outraged that the sex lives of private citizens was considered to be newsworthy material.[8] In 1978, three years after leaving the governorship, Reagan publicly opposed the Briggs Initiative, which would have banned gay men and lesbian women from teaching in California public schools; his opposition was key to the defeat of the initiative.[8] The Reagans, Nancy in particular, were also close with a number of openly gay men, as well as men whose homosexuality was an open secret, such as Roy Cohn, Jerry Zipkin, Truman Capote, and Ted Graber, whom the Reagans even invited to spend a night at the White House along with his partner.[11]

1980 Presidential election[edit]

Ronald Reagan was elected as President of the United States on November 4, 1980, and took office on January 20, 1981. The evangelical group Christians for Reagan, organized by Christian Voice, paid for a barrage of ads in Southern states during the final weeks of the election that attacked Reagan's opponent Jimmy Carter for his supposedly gay-friendly views.[12] The conservative Christian movement Moral Majority, led by Jerry Falwell, also backed Reagan, running television ads, fundraising and registration drives on his behalf.[13] In the end, Reagan won two-thirds of the white evangelical vote[14] (a voting block Carter had won in the 1976 Presidential election)[15] and swept every Southern state save for Carter's home state of Georgia, with religious fundamentalists greatly favoring Reagan even in comparison to conservative congressional candidates.[13]

Reagan administration response[edit]

Emergence of AIDS[edit]

First mention by the White House[edit]

On October 15, 1982, the White House answered its first question about the AIDS crisis,[16] marking the first official statement from the White House on AIDS.[9] At a regular White House Press Briefing, reporter Lester Kinsolving asked a question about AIDS, leading to the following exchange with White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes:

Kinsolving: Does the President have any reaction to the announcement by the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta that A-I-D-S is now an epidemic in 600- over 600 cases?

Speakes: [Mumbling under his breath] A-I-D-S. [Unintelligible]

Kinsolving: Over a third of them have died. It's known as "gay plague".

[Scattered laughter from the press pool.]

Kinsolving: No, it is. I mean, it's a pretty serious thing. One in every three people that get this have died. And I wonder if the President was aware of this.

Speakes: I don't have it. Are you-

[More scattered laughter.]

Speakes: Do you?

Kinsolving: You don't have it? Well, I'm relieved to hear that, Larry!

[Press pool laughter.]

Speakes: Do you?

Kinsolving: I'm delighted. No, I don't.

Speakes: You didn't answer my question. How do you know?

Kinsolving: Does the President- in other words, the White House looks on this as a great joke?

Speakes: No, I don't know anything about it Lester.

Kinsolving: Does the President? Does anybody in the White House know about this epidemic, Larry?

Speakes: I don't think so, I don't think there's been any-

Kinsolving: Nobody knows.

Speakes: There's been no personal experience here, Lester.

Kinsolving: No I mean, I thought you [unintelligable]

Speakes: Doctor- I checked thoroughly with Dr. Ruge this morning and he's had no, uh,

[Press pool laughter.]

Speakes: No patients suffered from A-I-D-S or whatever it is.

Subsequent questions from Kinsolving[edit]

Kinsolving, despite being personally against homosexuality, continued to press Speakes on the AIDS issue over the following years. On June 12, 1983, a second exchange on the topic of AIDS occurred between Kinsolving and Speakes, in which Speakes said that the President was "briefed on the AIDS situation a number of months ago," the first public indication that Reagan was aware of the AIDS epidemic.[9][17] As part of that same exchange, Speakes also jokingly insinuated that Kinsolving was gay himself, saying at a mention of fairy tales that "Lester's ears perked up when you said fairy."[18][19]

On December 11, 1984, Kinsolving asked another question about AIDS, his last such exchange for which known records exist.[19] Speakes noticed Kinsolving making his way to the front and called on him, leading to the following exchange:

Kinsolving: Since the Center for Disease Control in Atlanta-

[Laughter and chatter from press pool begins, and continues throughout.]

Speakes: [laughing] This is gonna be an AIDS question?

Kinsolving: ...that an estimated- [interrupted by chatter] Look, can I ask the question Larry? An estimated three hundred thousand people have been exposed to AIDS which can be transmitted through saliva.[a] Will the President as Commander in Chief take steps to protect armed forces who perform medical services from, um, AIDS patients, or those who run the risk of spreading AIDS in the same manner that they vet typhoid fever people from being involved in health or food services?

[Unintelligible cross-chatter and laughter.]

Kinsolving: Could you... [becoming angry] Is the President concerned about this subject Larry? That seems to have evoked so much jocular reaction here. I- you know-

Speakes: [overlapping] I haven't heard him express... concern. I haven't heard him express...

Unidentified speaker: It isn't only the jocks, Lester!

Unidentified speaker: Has he sworn off water faucets?[b]

Kinsolving: No but I mean, is he going to do anything, Larry?

Speakes: Lester, I have not heard him express anything on it. Sorry.

Kinsolving: You mean he has no- expressed no opinion about this epidemic?

Speakes: [mocking] No, but I must confess I haven't asked him about it.

Kinsolving: Would you ask him, Larry? [Conversation continues without question being answered.]

1983 meetings[edit]

On June 21, 1983, Reagan held a meeting with the National Gay Task Force representatives Virginia Apuzzo and Jeff Levi, alongside members of his own administration, including staff from the Department of Health and Human Services.[22] This marked the first time the Reagan administration had met with representatives of the LGBT community.[23] The meeting discussed concerns about the AIDS epidemic and basic solutions to it, such as encouraging condom usage to mitigate spread.[23]

However, Reagan was dissatisfied with his meeting with the task force, and in August of that year scheduled another meeting on the AIDS epidemic, this time without any representatives of the LGBT community, instead choosing to meet with conservative activists.[23] Attendees of this meeting included Director of the Office of Public Liaison Faith Whittlesey, National Director of the Conservative Caucus Howard Phillips and Moral Majority representative Ron Goodwin.[23] Goodwin advocated for closing gay bathhouses and requiring blood donors to provide sexual histories, while Phillips pushed for a position of only discussing the AIDS pandemic in the context of homosexuality as a moral failing, effectively putting the blame for AIDS on its victims for their homosexual nature.[23] Many conservatives of the era echoed similar sentiments.[24] Pat Buchanan, who would become the White House Communications Director for Reagan in 1985, wrote acerbically in a column on June 23, 1983: "The poor homosexuals. They have declared war on nature, and now nature is exacting an awful retribution."[25][24]

According to historian Jennifer Brier, these meetings and the attitudes prevailing in them deeply complicated epidemiologists' efforts. While public health leaders and epidemiologists from the Center for Disease Control (CDC) and National Institute of Health (NIH) attempted to gain control of the epidemic, they also had to contend with Reagan's conservative advisors and aides, who "wanted to bend what they called 'AIDS education' to fit the model of social and religious conservatism that posited gay men as sick and dangerous."[26] Brier further notes that, "Staff members were flooded with material with vitriolic attacks on homosexuality."[26] Following these 1983 meetings, there are no records of internal White House conversations on AIDS for 2 years.[22]

1984 Election[edit]

In the 1984 Presidential Election, Reagan was re-elected as president as he defeated Democratic challenger Walter Mondale in a landslide election. His support among evangelicals increased compared to 1980, as he won 78% of the evangelical vote, further entrenching his support in a group among whom many held deep antipathy for homosexuals and those with AIDS.[27] Neither Democratic candidate Walter Mondale nor Reagan made any public statement on the AIDS during the campaign, and no reporter raised the issue with the candidates.[28]

Funding for AIDS treatment and research[edit]

One of the major priorities of the Reagan administration was to slash the federal budget in all areas except the military, an economic policy which came to be known as Reaganomics, and public health agencies such as the CDC and NIH were no exception.[29] In the early 1980s, Reagan's director of the Office of Management and Budget, David Stockman, targeted public health agencies for massive cuts.[29] One such cut proposed slashing the budget for immunization by half, but was stopped by opposition from Henry Waxman and Pete Domenici.[29]

Prior to 1983, AIDS did not have specific funding, and research on AIDS instead had to be pulled from the CDC and NIH's general funding pools.[30] This left AIDS researchers severely constrained on funds, and slowed down their ability to understand, respond to and find a cure for the disease.[30] Some, including Henry Waxman, believed the amount of AIDS funding to be insubstantial, comparing it unfavorably to other diseases which had experienced outbreaks such as Legionnaire's disease and toxic shock syndrome.[31] According to one government study, in the 1982 fiscal year, toxic shock syndrome, which by that point was already well understood, received funding amounting to $36,100 per death, and Legionnaire's disease received $34,841 per death.[32] In comparison, AIDS research received just $8,991 per death.[32]

On April 12, 1983, Don Francis, then a CDC epidemiologist and AIDS researcher, wrote a memo to CDC Assistant Director Walter R. Dowdle asking for more resources to deal with the AIDS crisis, imploring that the current funding was not nearly adequate to deal with the epidemic, "The inadequate funding to date has seriously restricted our work and has presumably deepened the invasion of [AIDS] into the American population... it has sandwiched those responsible for research and control between massive pressure to do what is right and an ummovable wall of inadequate resources."[33]

On September 28, 1982, H.R. 7192, the first legislation to propose to fund AIDS research, was proposed in the House of Representatives by Representatives Phillip Burton and Ted Weiss, however the bill quickly died in committee.[34] On April 12, 1983, Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler testified to Congress that no additional funding was needed for AIDS research,[33] despite this, Congress passed the first specific funding for AIDS research on May 18, 1983, allocating $2.6 million, which Reagan signed.[34][35] According to congressional members who advocated for this funding, this was only accomplished by bundling AIDS funding together with funds for Legionnaire's disease and toxic shock syndrome in a Public Health Emergency Trust Fund.[29] This scenario continued to play in funding battles out over the following years until 1986, as noted by Randy Shilts:

Congress would have to discern for itself how much money government doctors needed to fight AIDS. The administration would resist but not put itself in the position of an on-the-record funding veto. The epidemic's research would survive from continuing resolution to continuing resolution, a game that would ultimately achieve some funding for the doctors while disabling any attempt to plan ahead for studies that might be needed as the scourge continued to grow.

Death of Rock Hudson[edit]

Diagnosis[edit]

On May 15, 1984, Rock Hudson, one of the biggest movie stars of the Golden Age of Hollywood and an acquaintance of the Reagans, attended a White House State Dinner for Mexican President Miguel de la Madrid with the Reagans. Hudson was gay but deeply closeted to the public, as his career was made on playing heartthrobs in heterosexual romance films.[36] At the dinner, Nancy Reagan noticed that Hudson looked gaunt, and when she sent him photos from the dinner, she urged him to get a doctor to look at the red blotch on his neck. When Hudson went for a checkup on June 5, 1984, doctors identified the blotch as Kaposi's sarcoma, and Hudson tested as HIV-positive.[37]

Hudson attempted to hide his illness throughout the rest of 1984 and well into 1985, despite the deterioration of his health. In his public appearances, he progressively appeared more and more emaciated, leading to public speculation on his health.[36][38] Finally, on July 25, 1985, after Hudson collapsed in Paris's Hôtel Ritz Paris, Hudson publicist Yanou Collart publicly confirmed that Hudson had AIDS.[39]

Hudson's plea[edit]

At the time Hudson was diagnosed, treatments for AIDS were still in their infancy, and even trials were unavailable in the United States.[11] In 1985, Hudson travelled to Paris, where he sought to seek treatment from Dominique Dormant, a French Army doctor who had secretly treated him for AIDS in the fall of 1984 with HPA-23.[40][41] After his collapse at the Ritz Hotel, Hudson was admitted to the American Hospital of Paris, however, Dormant was working at a military hospital, and was denied permission to admit Hudson, as Hudson was not a French citizen. Further, Dormant was at first not even able to enter the American Hospital in order to see Hudson.[40]

Staff and doctors at the American Hospital wanted to throw Hudson out, as they felt associating the renowned hospital with the "gay disease" of AIDS would tarnish its reputation, and pressure built on Hudson to transfer to the military hospital.[42] On July 24, 1985, Hudson sent a message to Nancy Reagan via telegram, in which he pleaded with her to ask the French government to admit him to the military hospital, the only hospital he believed had a chance of curing his illness, as Dormant thought that "a request from the White House or a high American official would change [the hospital commander's] mind."[40] Nancy turned down the request, instead forwarding it to the American consulate in Paris, and Hudson was ultimately not admitted to the hospital.[43][40] The reason given by Nancy was that the White House did not want to be seen as making exceptions for friends, though some critics have pointed out other occasions where the Reagans did appear to make exceptions or do favors for their friends.[9][40][44] The same day the telegram was received, President Reagan, who to that point still had not acknowledged AIDS publicly, called Hudson to wish him well.[11]

On July 24, 1985, thanks to Hudson publicist Yanou Collart's connections with French officials, Dormant was finally allowed to enter the American Hospital to see Hudson.[40] When Dormant saw him however, he realized that Hudson's HIV infection had progressed too far, and further HPA-23 treatments would be ineffective.[42] On July 28, 1985, Hudson chose to stop seeking treatment in Paris and return home, secretly chartering a Boeing 747 at a cost of more than $250,000 to return to Los Angeles, where he was taken to the UCLA Medical Center.[40] Two months later, on October 2, 1985, Hudson died of AIDS complications.[40]

Effects[edit]

It was commonly accepted now, among the people who had understood the threat for many years, that there were two clear phases to the disease in the United States: there was AIDS before Rock Hudson and AIDS after.

—Author and AIDS advocate Randy Shilts in his book And the Band Played On.[45]

The illness and death of Hudson marked a major turning point in the public perception of AIDS. Hudson, a man who was famous, masculine, and for most of his life perceived as heterosexual, brought new a new kind of understanding of those suffering from AIDS to the American public.[46] As Randy Shilts notes in And the Band Played On: "There were two clear phases to the disease in the United States: there was AIDS before Rock Hudson and AIDS after."[45] Just weeks after the death of Hudson, the United States Congress doubled the federal funds allocated to finding a cure for AIDS.[11]

Reagan was personally deeply affected by Hudson's battle with AIDS, despite the fact that in his own words he "never knew him too well".[47] According to John Hutton, a Brigadier General in the United States Army and one of Reagan's personal physicians in 1985, before it was announced that Hudson was dying of AIDS, Reagan believed that AIDS "was like measles and it would go away."[48] After seeing the reports that Hudson had AIDS, however, Reagan asked Hutton to explain the disease to him. After Hutton was done explaining, he says Reagan remarked, "I always thought the world might end in a flash, but this sounds like it's worse."[48] Ron Reagan, President Reagan's son, agreed that President Reagan needed the death of someone he personally knew to make him understand the problem with AIDS, as he noted, "My father has the sort of psychology where he grasps onto the single anecdote better than the broad wash of the problem."[49]

Reagan acknowledges AIDS[edit]

On September 17, 1985, less than two months after Hudson had come forward with his AIDS diagnosis, Reagan finally publicly acknowledged AIDS for the first time when he was asked a question about it by a reporter at a presidential press conference.[49] Since the CDC first announced the emergence of AIDS in 1981, thirty presidential news briefings had passed before Reagan was finally asked about AIDS.[49]

The reporter asked Reagan about the urging of the nation's "best-known AIDS scientist" that funding be greatly increased for AIDS research in a "moonshot" program, similar to the targeting of cancer in Richard Nixon's National Cancer Act of 1971.[50] Reagan responded by defending his administration's actions on AIDS to that point, describing it as one of the administration's "top priorities" and defending the amount of funding provided for AIDS research, claiming the funding would be increased the following year.[50] In a follow-up question, the same reporter noted that the scientist he cited was specifically discussing Reagan's proposed amount of funding and increases, and had called it "not nearly enough at this stage to go forward and really attack the problem." Reagan defended the amount budgeted as a "vital contribution" before moving on to other questions.[50]

Some, such as epidemiologist and HIV/AIDS researcher Don Francis, have challenged the idea that AIDS was a "top priority" for the Reagan administration. According to Francis, despite the public claim that AIDS was a top priority, "Within their own halls, the Reagan Administration maintained that federal health agencies should be able to meet the growing AIDS threat without extra funds, simply by shifting money from other projects."[30]

Koop Report[edit]

Commissioning and creation[edit]

On February 6, 1986, Reagan began his administration's first significant initiative against AIDS when he declared finding a cure for AIDS to be "one of our highest public health priorities" and ordered Surgeon General C. Everett Koop to assemble a "major report" on AIDS.[51][52] According to historian Jennifer Brier, administration officials believed that Koop, a conservative Presbyterian, would write a report that would emphasize morality and sex only within the confines of heterosexual marriage as the solution to AIDS.[53] Henry Waxman, then the chair of the United States House Energy Subcommittee on Health and an AIDS advocate, criticized the Reagan administration's request of the report, accusing them of playing a "shell game" with federal funding as he noted that on the same day, the Reagan administration had also proposed a budget which included a $51 million cut to AIDS funding for the following fiscal year.[51]

Koop enlisted the help of Anthony Fauci, his personal physician and the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, to learn more about HIV and AIDS, undertaking, according to Karen Tumulty, a "full scale effort to discover everything that could be known about AIDS."[52] As part of his research process, Koop invited representatives from 26 different groups with a wide range of opinions on the AIDS crisis, including the Southern Baptist Convention, Gay Men's Health Crisis and the National Coalition of Black Lesbians, to hold confidential meetings in his office where he listened to their perspectives on the AIDS crisis.[54] Richard Dunne, invited as a representative of Gay Men's Health Crisis, said of his meeting with Koop, "One of the things that impressed me is that he really listened, and most people at that level find it hard to do so."[54] The report went through 26 drafts before Koop felt it was ready to release.[54] Believing the Reagan administration would censor the report if given the chance, Koop chose not to submit it for an internal review with Reagan's policy advisors before releasing the report to the public.[55]

Contents[edit]

The 36 page report was released on October 22, 1986, and was an immediate bombshell.[55] The report projected that by 1991, 270,000 Americans would contract HIV/AIDS and 179,000 would die of it. At the suggestion of Anthony Fauci,[54] the report was unsparing in its language, describing the methods of transmission of AIDS through "semen and vaginal fluids" during "oral, anal and vaginal intercourse," while also correcting common myths about AIDS, such as the ability to contract it from saliva or mosquito bites.[55] While Koop acknowledged that abstinence was the only way to guarantee AIDS prevention, he also suggested teaching the use of protection to stymie its spread.[55] He also argued that since "information and education are the only weapons against AIDS," AIDS education needed to begin as early as possible, specifically citing third grade as the age at which he would like to begin AIDS education, and noted that sex education needed to contain information on both heterosexual and homosexual sex.[56] Further, he advocated for confidential, optional testing in order to encourage people at-risk to get tested, as those at the highest risk of AIDS, such as queer people and drug users, often lived on the outskirts of society.[56] This went against a popular conservative position of the time, which was that of mandatory testing for those at risk, as well as a public registrar of those with AIDS.[52]

Reactions[edit]

I feel you can never separate your faith from yourself. On the other hand, I am the surgeon general, not the chaplain of the public health service.

—C. Everett Koop[54]

Reactions to the report among conservatives were sharply negative. Phyllis Schlafly was said to have been incensed by the report, saying it "looks and reads like it was edited by the Gay Task Force". She further accused Koop of advocating for teaching third graders "safe sodomy".[57] Responding to this, Koop said to reporters, "I'm not Surgeon General to make Phyllis Schafly happy. I'm Surgeon General to save lives." He is almost reported to have later bemoaned of Schlafly, "Why anybody listened to this lady is one of the mysteries of the eighties."[57] Reagan aide Gary Bauer was so frustrated by Koop's report that he began an internal investigation into Koop's research and sources, ostensibly out of apprehension that the government was "preparing materials that [were] offensive to people concerned about their children's education."[58]

Reagan was described as "uncomfortable" with the report's implications, saying of its recommendation for comprehensive sex education over abstinence-only sex education, "I would think that sex education should begin with the moral ramifications, that it is not just a physical activity that doesn’t have any moral connotation."[55] Reagan's Secretary of Education William Bennett also reacted negatively to the Koop report, and made abstinence-only sex education one of his top priorities while ridiculing Koop's advice to teach condom usage.[54]

Most on the other side of the aisle, however, including former Koop critics Henry Waxman and Edward Kennedy were surprised by the report's frankness and happy with its contents. As Koop was a deeply faithful conservative Presbyterian,[52] his appointment had been opposed by a number of prominent liberals on the grounds that he was unqualified—Koop's background was in pediatric surgery, not public health—and that his religion would bias him away from medical or science based decision making.[54][56] Koop soon gained a reputation among liberals as "the only straight shooter in the Reagan administration," and some, including Waxman and Kennedy, even apologized for their opposition to his nomination.[54] Gay activists were described as shocked that their advice had been taken into consideration and included in the report.[54]

The Reagan administration did not ultimately act directly on the report's suggestions, however, in 1988, a version of the report was turned into a brochure called Understanding AIDS. On May 5, 1988, it was announced that a copy of the brochure would be mailed to every household in America, numbering 107 million copies, making it the largest mass-mailing in US history at the time.[59] The decision to mail the brochure was made by Koop, under a mandate from the United States Congress.[56]

Speech at the American Foundation for AIDS Research[edit]

In the spring of 1987, Elizabeth Taylor, a longtime friend of Nancy Reagan, co-star and confidant of Rock Hudson, and the national chairperson of amFAR, invited President Reagan to speak to speak at an amFAR fundraising dinner, which would precede a massive scientific conference on AIDS.[60] Reagan accepted the offer, and began preparing for what would be his first speech on the subject of AIDS.[61] Landon Parvin, an outside consultant and Nancy's favorite among Reagan's speechwriters, was brought in to write the speech, as the Reagans were aware that the audience would likely be hostile.[60]

In the course of creating the address, Parvin discovered that the President had never actually had a meeting with C. Everett Koop about AIDS. He arranged for Reagan and Koop to have a one-on-one meeting on the subject, but the White House insisted on adding political advisors such as William Bennett and Gary Bauer to the meeting, resulting in an argument between Koop, who favored emphasizing what was known about the spread of AIDS from a medical perspective, and the conservative advisors, who wanted to blame the lifestyle choices (such as drug use and homosexuality) of the victims.[60] In the end, however, Parvin mostly favored Koop's perspective, and none of the most extreme conservative suggestions made it into the speech.[60]

Reagan delivered the address on May 31, 1987. The audience, many of whom had AIDS, booed and jeered Reagan several times throughout the speech.[62] The speech emphasized that compassion for AIDS victims, and the need to educate the public better on how AIDS spreads, however, several parts were unpopular with the audience, such as one passage where Reagan gives his sympathy to the suffering of some specific groups susceptible to HIV infection, such as hemophiliacs and the babies of infected women, but notably left out any mention of gay people; in fact, the words "gay" or "homosexual" are conspicuously absent from the entire speech.[62][63] The audience also reacted negatively when the President called for routine AIDS testing of immigrants, prisoners, and marriage-license applicants, as well as mandatory AIDS screening for immigrants.[62]

Parvin later said of the speech, "There was some good stuff in it, but not enough."[62] Still, the speech marked a turning point for Reagan's public acknowledgement of AIDS, and Reagan himself wrote that he was "pleased with the whole affair" despite the boos.[64] Two months later, Reagan visited the National Cancer Institute to hold an HIV-positive 14-month-old baby.[11]

Watkins Commission[edit]

Creation of the commission and membership[edit]

On June 24, 1987, Reagan issued Executive Order 12601, creating the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic to investigate HIV/AIDS.[65] Quickly, the Reagan administration was inundated with suggestions for committee members from across the political spectrum.[66] Senator Strom Thurmond proposed Paul Cameron, an ex-psychologist from Nebraska who wanted to institute a "rolling quarantine" of homosexuals.[66] Other nominees included Stephen Herbits,[c] Eunice Kennedy Shriver, Barbara Jordan, Bob Bauman,[d] and William F. Buckley,[e][66] a right-wing publicist who proposed to permanently tattoo all people who tested positive for AIDS.[67][11]

Nancy Reagan pushed strongly for the inclusion of a gay man on the committee, believing it was important for one of the groups most affected by AIDS to have representation.[68][66] She was opposed by Reagan aide Gary Bauer, who was strongly against including any homosexual person in the commission.[66] He argued to Reagan that they would not consider including an IV drug user, and thus there was no reason to include a gay person. In a memo on June 30, 1987, Bauer wrote to Reagan, "Millions of Americans try to raise their children to believe that homosexuality is immoral. For you to appoint a known homosexual to a Presidential Commission will give homosexuality a stamp of acceptability. It will drive a wedge between us and many of our socially conservative supporters."[69] He urged Reagan that if he had to include a homosexual person, he should make it a "reformed" homosexual who was not currently in a homosexual relationship.[69]

In the end however, Nancy's pressure on her husband won out, and at the recommendation of her stepbrother (who was a doctor), Frank Lilly, a board member of the Gay Men's Health Crisis organization and the chairperson of the Albert Einstein College of Medicine genetics department, was chosen for a spot on the commission.[68] Lilly's appointment to the commission proved to be especially controversial, as it was attacked for legitimizing the "homosexual lifestyle" by conservatives including Republican Senator Gordon Humphrey, who complained the administration "should strive at all costs to avoid sending the message to society—especially to impressionable youth—that homosexuality is simply an alternative lifestyle."[68] Far-right writer Joseph Sobran similarly protested of Lilly's nomination that it was giving "legitimacy to the homosexual" and cited the reason for the nomination as Nancy Reagan's inner circle "containing a number of the breed[f] over the years."[69]

Controversial among AIDS groups, however, was the snub of any AIDS advocate for a spot on the committee, with the National Association of People with AIDS even unsuccessfully attempting to sue the President over the lack of an AIDS advocacy representative on the commission.[70] According to historian Jennifer Brier, most members of the commission were chosen for their conservative backgrounds, though the appointment of Eugene Mayberry, the head of the Mayo Clinic, as the chairperson of the committee gave some advocates hope.[70]

On October 8, 1987, however, after months of infighting and little progress, Mayberry resigned from the post alongside Health Commissioner of Indiana Woodrow Myers, with both claiming they were unable to accomplish their goals in a group that also contained people acting on political, rather than medical, motivations.[70] Following these departures, Reagan appointed Admiral James D. Watkins of the US Navy as the new chairman of the committee.[70]

Report[edit]

The Watkins Commission report was released on June 27, 1988. The report was unflinching in its assessment of the government's response to that point, describing a "lack of leadership" as one of the biggest obstacles to progress against AIDS.[71] The Watkins Commission report also made a number of policy suggestions, many of which overlapped with the suggestions in the Koop Report. In total, the 203-page report makes 579 specific recommendations for fighting AIDS,[72] including:

- A push for public understanding and federal legislation to fight discrimination against individuals with AIDS, and calling on the Reagan administration to cease their opposition to such a law.[72]

- Comprehensive public education about AIDS, starting in kindergarten and continuing through grade 12.[73]

- $3 billion more per year for funding against AIDS for federal, state, and local governments.[72]

- New emergency powers for the Surgeon General, in order to act quickly in the event of public health crises.[72]

- Ensuring "rigorous maintenance of confidentiality" for all HIV/AIDS victims.[74]

- Notifications to all people who received a blood transfusion since 1977 (when HIV was believed to have entered the blood supply) to inform them they should be tested for AIDS.[75]

Implementation of the report's suggestions[edit]

On August 2, 1988, Reagan outlined a 10 point "action plan" against AIDS based on the Watkins Commission report. The plan implemented some of the report's proposed policies, such as notices to those who received blood transfusions between 1977 and 1985 that they should get tested for AIDS, barring federal discrimination against civilian employees with AIDS, and an increase in local programs to help provide AIDS education to those at high risk of AIDS infection.[76] However, the plan stopped short of many of the report's major suggestions, as the President declined to support a national ban on discrimination against those with AIDS.[76] The Reagan administration did not implement any more of the report's policy proposals before Reagan's term ended in January 1989.[76]

AIDS advocates were generally unhappy with Reagan's actions, believing they did not go nearly far enough and ignored the Watkins Commission report's central recommendations.[72] AIDS advocate Elizabeth Glaser, who had personally lobbied Reagan to listen to the commission's report, said of the administration's implementation, "Time went by, and nothing happened. It was almost unimaginable, but the White House took the report and put it on the shelf."[72]

Personal views of Reagan[edit]

Reagan was a Christian and did personally believe that homosexuality was a sin. In early 1987, Reagan had a discussion on the AIDS epidemic with his biographer, Edmund Morris, in which Reagan speculated "maybe the Lord brought down this plague" because "illicit sex is against the Ten Commandments."[77] According to John Hutton, one of Reagan's personal physicians, when private citizens would ask Reagan what should be done about AIDS, he would often respond that "money might not be the answer" and that "perhaps people are supposed to modify their behaviors."[48]

Reagan was also known to frequently make homophobic jokes, or mockingly act in an effeminate way to get a laugh.[11] In October 1986, Bob Woodward reported in the Washington Post on an exchange between Reagan and Secretary of State George Shultz which appeared to make light of the AIDS crisis. During a national security meeting, Reagan made a note of Muammar Gaddafi's eccentric taste in wardrobe, and joked "Why not invite Gaddafi to San Francisco, he likes to dress up so much?"[g] Schultz responded, "Why don’t we give him AIDS!" to laughter.[79][80] The City of San Francisco demanded an apology after the printing of these comments, to both the city and victims of AIDS.[79]

Reagan was well known for keeping a diary that he would unfailingly update every day. However, mentions of AIDS in these diaries are sparse — on June 24, 1985, Reagan mentions AIDS in reference to learning from a report on television that Rock Hudson may have had AIDS, rather than cancer as had been previously reported. After this entry, it was more than two years before Reagan again mentioned AIDS in his writing.[11]

Advocacy by Nancy and Ron Reagan[edit]

Reagan's son, Ron, and his wife, Nancy, were both privately sympathetic to LGBT movements, and attempted at various points to lobby Reagan to do more about the AIDS crisis.[36] Nancy had long had many gay men in her circle of friends, and Ron knew people who were suffering from AIDS from his time ballet dancing in New York City's Joffrey Ballet.[11] In 1987, Ron's disagreements with his father's policies began to cross from private into the public sphere. In July 1987, Ron starred in a television commercial criticizing his father's administration for its inaction on the AIDS pandemic. In the commercial, Ron urged the audience: "The U.S. government isn’t moving fast enough to stop the spread of AIDS. Write to your congressman," before adding with a smile, "or someone higher up."[81] He also appeared in a 30-minute public service announcement on AIDS, which was shown on PBS, in which he taught the audience how to use a condom and spermicide and encourages viewers to use them.[81] These public disagreements frustrated the elder Reagan, who wrote in his diary on July 18, 1987 that he disagreed with his son's stances, complaining that "[Ron] can be stubborn on a couple of issues & won’t listen to anyone’s argument."[81]

Meeting with Elizabeth Glaser[edit]

In June of 1988, a friend of the Reagans put them in contact with AIDS advocate Elizabeth Glaser. Glaser had unknowingly contracted HIV through a blood transfusion when she was giving birth to her first child in 1981 and had inadvertently given it to both of her children, Ariel, born in 1981, and Jake, born in 1984.[82] Although a few treatments, such as AZT, were available for AIDS treatment by that point, none of them were approved for use in children. Glaser believed that as a white heterosexual woman and a mother of two AIDS-stricken children, she may be able to change the Reagans' views on AIDS more effectively than LGBT activists, and so she reached out to a mutual friend who put her in contact with the Reagans.[82]

At their meeting the week before the Watkins Commission report was released, Glaser told the Reagans the story of her and her children's battles with AIDS, reportedly bringing them to tears. As Glaser prepared to leave, President Reagan asked her, "Tell me what you want me to do."[83] Glaser reportedly asked him to "be a leader in the struggle against AIDS" so her children could go to school without discrimination, and to listen to what the Watkins Commission report would say when it was released. Reagan promised that he would "read that report with different eyes than I would have before."[83] Despite this, however, the Reagan administration only acted on some of the report's suggestions, upsetting Glaser as she said of Reagan's actions on the report, "Hope for thousands of Americans and people around the world sat gathering dust in some forgotten corner of some forgotten room."[72]

Post-presidency[edit]

Reagan's final term as president ended on January 20, 1989, as his Vice President George H.W. Bush was sworn in as his successor. In 1989, the Reagans called Elizabeth Glaser to give their condolences after Glaser's daughter, Ariel, passed away from AIDS complications.[84] In 1990, Reagan appeared in a PSA with Glaser in which he offered what has been described by some as tacit regret for his administration's handling of the AIDS crisis, as he says in the PSA: "I’m not asking you to send money. I’m asking you for something more important: your understanding. Maybe it’s time we all learned something new."[84] Reagan also headlined a fundraiser in 1990 for Glaser's organization, the Pediatric AIDS Foundation. At the fundraiser, Reagan was asked by a reporter if he wished his administration had done more about AIDS, to which he responded, "We did all that we could at the time."[85]

Timeline of the Reagan administration's AIDS response[edit]

Key[edit]

| No highlight | Notable AIDS related event |

|---|---|

| Green highlight | Events in the Reagan administration |

| Yellow highlight | AIDS policies put into place by the Reagan administration |

| Red highlight | Major congressional actions on AIDS |

Timeline[edit]

| Date | Event |

|---|---|

| January 20, 1981 | Ronald Reagan is inaugurated as President of the United States. |

| Mid-1981 | Doctors in New York and Los Angeles first identify the disease which will come to be known as AIDS. At the time, the only known patients are gay men.[11] |

| October 15, 1982 | White House Press Secretary Larry Speakes fields a question about HIV/AIDS, the first time anybody from the Reagan administration had publicly acknowledged the disease, though Speakes' answer dismissive.[86] |

| December 31, 1982 | A total of 618 Americans are estimated to have died from AIDS complications.[87] |

| April 12, 1983 | Reagan's Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler tells Congress that no additional AIDS funding is necessary to deal with the crisis.[33] |

| May 18, 1983 | Congress passes the first specific funding for AIDS research and treatment, bundling it in a Public Health Emergency Trust Fund alongside funding for Legionnaire's disease and toxic shock syndrome.[34][29] |

| June 13, 1983 | Larry Speakes says in a press conference that the President was "briefed on the AIDS situation a number of months ago".[88] |

| June 21, 1983 | Reagan and staff from the Department of Health and Human Services meet with activists from the National Gay Task Force to discuss concerns about the AIDS epidemic, however, the meeting goes poorly, and Reagan does not meet with the activists again.[23] |

| August 1983 | Reagan meets with a number of religious conservative activists, who suggest framing AIDS as a consequence of the "moral failings" of homosexuality.[23] |

| December 31, 1983 | A total of 2,118 Americans are estimated to have died from AIDS complications.[87] |

| April 23, 1984 | United States Secretary of Health and Human Services Margaret Heckler announces at a press conference that an American scientist, Robert Gallo, has discovered the probable cause of AIDS, a retrovirus which will come to be know as HIV.[34] |

| December 11, 1984 | Larry Speakes, in responding to a question from Lester Kinsolving, states that he has not heard Reagan express any thoughts or opinions on the AIDS epidemic.[17] |

| December 31, 1984 | A total of 5,596 Americans are estimated to have died from AIDS complications.[87] |

| February 1985 | The Reagan administration proposes a $10 million cut to AIDS research funding for the following fiscal year.[40] |

| July 25, 1985 | Rock Hudson, a prominent movie star and acquaintance of the Reagans, releases a public statement that he is dying of AIDS.[39] |

| September 17, 1985 | President Reagan publicly acknowledges AIDS for the first time in his response to a reporter's question.[89] |

| October 2, 1985 | Congress approves a budget of $190 million for AIDS research, $70 million more than the amount requested by the Reagan administration and nearly double the previous year's spending.[90] |

| December 31, 1985 | A total of 15,527 Americans are estimated to have died from AIDS complications.[87] |

| February 6, 1986 | Reagan declares a cure for AIDS to be a "top health priority" and orders C. Everett Koop to put together a major report on the subject.[51] |

| October 22, 1986 | The Koop report is released, outlining the causes of AIDS and advocating for comprehensive sex education to stymie its spread.[11] |

| December 31, 1986 | A total of 24,559 Americans are estimated to have died from AIDS complications.[87] |

| March 19, 1987 | AZT is approved by the FDA, becoming the first approved treatment for AIDS.[6] |

| May 31, 1987 | Reagan gives a speech, his first on the subject of AIDS, at an event for the American Foundation for AIDS Research and is booed by the attending crowd.[11] |

| June 24, 1987 | President Reagan forms the President's Commission on the HIV Epidemic to investigate the AIDS pandemic.[34] |

| December 31, 1987 | A total of 40,849 Americans are estimated to have died from AIDS complications.[87] |

| May 26, 1988 | Under a mandate from Congress, deliveries of Understanding AIDS, a brochure derived from the Koop report, begin to every household in the United States.[59] |

| June 24, 1988 | The President's Commission on the HIV Epidemic releases its final report, which is critical of the government's response to the AIDS crisis to that point and suggests a number of policy changes, including AIDS education starting in Kindergarten and a national law which would ban discrimination against people with AIDS.[11] |

| August 2, 1988 | The Reagan administration announces a 10 point "action plan" to implement suggestions in the HIV Commission's report, though it stops short of some of the report's major suggestions, including a national ban on discrimination against those with AIDS.[76] |

| December 31, 1988 | A total of 61,816 Americans are estimated to have died from AIDS complications.[87] |

| January 20, 1989 | Ronald Reagan leaves office. |

Legacy[edit]

Through the lack of both policy and financial support, the United States Centers for Disease Control (CDC) was severely handicapped during the early years of the AIDS epidemic. Senior staff of the Reagan Administration did not understand the essential role of Government in disease prevention. Although CDC clearly documented the dangers of HIV and AIDS early in the epidemic, refusal by the White House to deliver prevention programs then certainly allowed HIV to become more widely seeded.

—Center for Disease Control epidemiologist and HIV/AIDS researcher Don Francis in his 2012 paper Deadly Aids Policy Failure by the Highest Levels of the US Government: A Personal Look Back 30 Years Later for Lessons to Respond Better to Future Epidemics[30]

With few exceptions, Reagan's response to AIDS has been criticized by LGBT and AIDS activists,[91][11][92][93][94] epidemiologists,[95][30] and progressives.[96][97] The policies implemented by the Reagan administration are often characterized as too little and too late in the pandemic.[8] Some have accused Reagan of being motivated by homophobia to not respond to the pandemic,[98][91][99] though this assessment is controversial, with some commentators citing other factors such as political inconvenience or ignorance as the cause.[91][9][8][94]

Anthony Fauci, the head of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases from 1984 to 2022, has been quoted as saying about Reagan's response to the AIDS crisis, "it was clear there was a sort of muted silence about things."[61] Henry Waxman, the chair of the United States House Energy Subcommittee on Health during the 1980s, said that the government's AIDS response would have been different "if the same disease had appeared among Americans of Norwegian descent, or among tennis players".[95] Elizabeth Glaser, who had lobbied Reagan to act on the Watkins Commission report, endorsed Bill Clinton for the presidency in 1992, in a speech at the 1992 Democratic National Convention sharply critical of the Reagan administration's AIDS response.[11] Pundit James Kirchick compared the Reagan administration's response to that of Reagan's conservative counterpart in the United Kingdom, Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher, whose government quickly instituted a widespread public health and awareness campaign against AIDS. Kirchick cites the different government reactions as a reason why during the 1980s the rate of HIV infection in the Great Britain was much lower than the United States's.[100]

Some conservatives, as well as a small number of liberals, have defended the Reagan administration's response to the AIDS pandemic. Some defenders cite Reagan's opposition to some anti-LGBT measures, such as the Briggs Initiative to ban gay and lesbian teachers in California, as evidence against his prejudice against the LGBT community.[91][99] Others argue that his response was sufficient given what was known about AIDS, and that the federal government did spend large sums of money fighting AIDS during the 1980s, especially the latter half.[91][99] One argument from lawyer Peter W. Huber credits Reagan with appointing C. Everett Koop and James D. Watkins to their positions, in which they were able to take actions against AIDS.[101] Additionally, as part of Reaganomics, much deregulation was applied to the drug approval process of the Federal Drug Administration (FDA), which Huber argued allowed AZT and other AIDS treatments to be approved faster and save lives.[101]

Gay rights movement[edit]

The Reagan administration's perceived neglect of the AIDS crisis ignited a wave of LGBT advocacy.[102] LGBT-centered AIDS advocacy organizations such as Gay Men's Health Crisis and direct action group ACT UP were formed to pressure the government into acting on AIDS.[103] The Second National March on Washington for Lesbian and Gay Rights, also known as the Great March, was a large demonstration for LGBT rights which was motivated in part by anger over the government's AIDS response.[104] Avram Finkelstein, one of the creators of the famous Silence=Death poster, cited Reagan's silence on AIDS while his friends and partner died as a "private devastation" which motivated him to start the Silence=Death project.[103]

Historian and gay activist William Percy has argued that AIDS marked a considerable change in LGBT activism in the United States, which he called the "third epoch" of the American LGBT movement.[105] Percy contended that while the advocacy of the 1960s and 70s and been exuberant and deliberately provocative, with a focus on sexual liberation, AIDS forced the gay rights movement to become more politically correct and engage in self censorship in order to gain more common acceptance and support for AIDS healthcare.[105]

In popular culture[edit]

On April 21, 1985, playwright Larry Kramer debuted his autobiographical play The Normal Heart, a major subject of which is the lack of attention given to AIDS by the American public and the Reagan administration.[89] The play was adapted into a 2014 film of the same name starring Mark Ruffalo.[89][91] Randy Shilts's book And the Band Played On was also adapted into a 1994 HBO television film of the same name, starring Matthew Modine as Don Francis.

On March 11, 2016, during the 2016 Democratic Party presidential primaries, at the funeral of Nancy Reagan, candidate and future Democratic Party nominee Hillary Clinton credited Ronald and Nancy Reagan with starting a national conversation on AIDS "when before nobody would talk about it, nobody wanted to do anything about it."[96][106] Her remarks were criticized as an inaccurate characterization of the Reagans' response to AIDS by LGBT and AIDS advocates as well as her primary opponent, Bernie Sanders.[96][106][97] She later apologized for her remarks.[96]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ This is not true. HIV, the virus which causes AIDS, can be transmitted via a number of fluids, however saliva is not one of them.[20] The idea that HIV/AIDS could be transmitted through saliva was, however, a common misconception at the time.[21]

- ^ The misconception which is being referenced here, either derisively or out of genuine misunderstanding, is that HIV can be spread by drinking out of the same water fountain as an infected person.[21]

- ^ Nominated by Dick Cheney.[66]

- ^ Nominated by himself.[66]

- ^ Nominated by Gary Bauer.[66]

- ^ Referring to gay men.

- ^ San Francisco is famously a very LGBT-friendly city, and at the time was in the throws of one of the country's deadliest AIDS outbreaks.[78]

References[edit]

- ^ Tumulty 2021a, p. 411.

- ^ Pasteur Institute 2023.

- ^ Shampo & Kyle 2002.

- ^ Sabin 2013.

- ^ Shilts 1987, p. 597.

- ^ a b Corbett 2010.

- ^ HRC 2017.

- ^ a b c d e Ambinder 2015.

- ^ a b c d e Evans 2018.

- ^ Harrity 2016.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o Tumulty 2021b.

- ^ Djupe & Olson 2003, p. 99.

- ^ a b Miller & Wattenberg 1984.

- ^ Graham 1997.

- ^ Williams 2020, p. x.

- ^ Schudel 2018.

- ^ a b Lopez 2016a.

- ^ Harmon 2015.

- ^ a b Lawson 2015.

- ^ CDC 2022.

- ^ a b Kaplan 2022.

- ^ a b Brier 2009, p. 83.

- ^ a b c d e f g Petro 2015, p. 67.

- ^ a b Tumulty 2021a, p. 418.

- ^ Washington Post 1987.

- ^ a b Brier 2009, p. 84.

- ^ Kirchick 2022, p. 577: "A Los Angeles Times poll reported that more than half of American adults supported quarantining AIDS patients, and a conservative pollster found that a third of the public supported quarantining all male homosexuals, a distinction, apparently in the minds of many, without a difference. The antipathy was particularly strong among evangelicals, 78% of whom voted for Reagan in 1984."

- ^ Shilts 1987, p. 495.

- ^ a b c d e Green 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Francis 2012.

- ^ Shilts 1987, p. 143.

- ^ a b Shilts 1987, p. 186.

- ^ a b c PBS 2006.

- ^ a b c d e hiv.gov HIV/AIDS Timeline.

- ^ a b Shilts 1987, p. 214.

- ^ a b c Tumulty 2021a, p. 415.

- ^ Shilts 1987, p. 456.

- ^ Shilts 1987, p. 544.

- ^ a b The New York Times 1985.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Geidner 2015.

- ^ Shilts 1987, p. 573.

- ^ a b Shilts 1987, p. 577.

- ^ Tumulty 2021a, p. 417.

- ^ Kirchick 2022, p. 574.

- ^ a b Shilts 1987, p. 585.

- ^ Shilts 1987, p. 588.

- ^ Ronald Reagan Diary for 24 July 1985.

- ^ a b c The New York Times 1989.

- ^ a b c Kirchick 2022, p. 573.

- ^ a b c Presidential Press Conference on 17 September 1985.

- ^ a b c Weinraub 1986.

- ^ a b c d Tumulty 2021a, p. 419.

- ^ Brier 2009, p. 88.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i Boodman 1987.

- ^ a b c d e Tumulty 2021a, p. 420.

- ^ a b c d Profiles in Science 2019.

- ^ a b Petro 2015, p. 72.

- ^ Brier 2009, p. 90.

- ^ a b The New York Times 1988.

- ^ a b c d Tumulty 2021a, p. 422.

- ^ a b Tumulty 2021a, p. 412.

- ^ a b c d Tumulty 2021a, p. 424.

- ^ Reagan 1987.

- ^ Ronald Reagan Diary for 31 May 1987.

- ^ National Archives - Reagan Executive Orders of 1987.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Kirchick 2022, p. 616.

- ^ Kirchick 2022, p. 578.

- ^ a b c Tumulty 2021a, p. 426.

- ^ a b c Kirchick 2022, p. 617.

- ^ a b c d Brier 2009, p. 95.

- ^ Report of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic 1988.

- ^ a b c d e f g Tumulty 2021a, p. 429.

- ^ Report of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic 1988: "Age appropriate, comprehensive health education programs in our nation's schools, in kindergarten through grade twelve, should be a national priority. "

- ^ Report of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic 1988, p. 126.

- ^ Report of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic 1988, p. 78-80.

- ^ a b c d Orlando Sentinel 1988.

- ^ Tumulty 2021a, p. 620.

- ^ Katz 1997.

- ^ a b Tumulty 2021a, p. 414.

- ^ Kirchick 2022, p. 575: "During a meeting with his top national security officials to discuss a psychological warfare operation against the Libyan strongman Muammar Gaddafi, Reagan allegedly made a joke about his garish wardrobe. "Why not invite Gaddafi to San Francisco, he likes to dress up so much," the president said. "Why don't we give him AIDS!" Secretary of State George Shultz interjected. "Others at the table laughed," according to a report by Bob Woodward in the Washington Post."

- ^ a b c Tumulty 2021a, p. 421.

- ^ a b Tumulty 2021a, p. 427.

- ^ a b Tumulty 2021a, p. 428.

- ^ a b Tumulty 2021a, p. 430.

- ^ Higgins 2019.

- ^ Gibson 2015.

- ^ a b c d e f g amfAR Snapshots of an Epidemic.

- ^ White House Press Briefing 1983.

- ^ a b c King 2020.

- ^ Shepard 1985.

- ^ a b c d e f Mason 2014.

- ^ San Francisco AIDS Foundation 2011.

- ^ Davis 2022.

- ^ a b La Ganga 2016.

- ^ a b Fauci 2012.

- ^ a b c d Brydum 2016.

- ^ a b Villarreal 2016.

- ^ Kirchick 2022, p. 556.

- ^ a b c Murdock 2012.

- ^ Kirchick 2022, p. 619: "By contrast, in Great Britain, Reagan's conservative ally Margaret Thatcher implemented a robustly funded public health awareness campaign, and the incidence of HIV infection was one-tenth that of the United States."

- ^ a b Huber 2016.

- ^ Huneke 2022, p. 179.

- ^ a b Fitzsimons 2018.

- ^ Ghaziani 2008, p. 168.

- ^ a b Percy 2005.

- ^ a b Lopez 2016b.

Works cited[edit]

Books[edit]

- Tumulty, Karen (April 13, 2021a). The Triumph of Nancy Reagan. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 9781501165207.

- Djupe, Paul A.; Olson, Laura R. (May 1, 2003). Encyclopedia of American Religion and Politics. Facts on File, Inc. ISBN 978-0816045822. Retrieved October 29, 2013.

- Williams, Daniel K. (2020). The Election of the Evangelical. University Press of Kansas. ISBN 9780700629121.

- Petro, Anthony Michael (2015). After the Wrath of God: AIDS, Sexuality, and American Religion. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780199391288.

- Brier, Jennifer (2009). Infectious Ideas: U.S. Political Responses to the AIDS Crisis. University of North Carolina Press. ISBN 9780807833148.

- Kirchick, James (2022). Secret City: The Hidden History of Gay Washington. Henry Holt and Company. ISBN 9781627792332.

- Shilts, Randy (1987). And the Band Played on: Politics, People, and the AIDS Epidemic. Penguin Books. ISBN 9780140113693.

- Huneke, Samuel Clowes (2022). States of Liberation: Gay Men between Dictatorship and Democracy in Cold War Germany. University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-1-4875-4213-9.

- Ghaziani, Amin (2008). The Dividends of Dissent: How Conflict and Culture Work in Lesbian and Gay Marches on Washington. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 9780226289960.

Journals[edit]

- Miller, Arthur H.; Wattenberg, Martin P. (January 1, 1984). "Politics from the Pulpit: Religiosity and the 1980 Elections" (PDF). Public Opinion Quarterly. 48 (1B): 301–317. doi:10.1093/poq/48.1B.301. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Katz, M H (1997). "AIDS Epidemic in San Francisco Among Men Who Report Sex with Men". Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes and Human Retrovirology. 14: S38–S46. doi:10.1097/00042560-199700002-00008. PMID 9070513. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- Francis, Donald (August 2012). "Commentary: Deadly AIDS policy failure by the highest levels of the US government: A personal look back 30 years later for lessons to respond better to future epidemics" (PDF). Journal of Public Health Policy. 33 (3): 290–300. doi:10.1057/jphp.2012.14. JSTOR 23253449. PMID 22895498. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- Sabin, Caroline A (November 27, 2013). "Do people with HIV infection have a normal life expectancy in the era of combination antiretroviral therapy?". BMC Medicine. 11: 251. doi:10.1186/1741-7015-11-251. PMC 4220799. PMID 24283830.

- Shampo, Marc A.; Kyle, Robert A. (June 2002). "Luc Montagnier—Discoverer of the AIDS Virus". Mayo Clinic Proceedings. 77 (6): 506. doi:10.4065/77.6.506. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

Other[edit]

- King, Jack (October 19, 2020). "The drama that raged against Reagan's America". BBC News. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Ambinder, Marc (January 11, 2015). "When Ronald Reagan (sort of) fought for the dignity of gays". The Week. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Evans, Robert (October 9, 2018). "Ronald and Nancy Reagan: The Bastards Behind the AIDS Crisis" (Podcast). Behind the Bastards. iHeartRadio. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Fauci, Anthony (November 27, 2012). Dr. Fauci's Remarks: Introduction and Presentation of 2012 C. Everett Koop Award to Rep. Waxman (Speech). 2012 C. Everett Koop Award. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Graham, Billy (March 22, 1997). "When worlds collide: politics, religion, and media at the 1970 East Tennessee Billy Graham Crusade. (appearance by President Richard M. Nixon)". Journal of Church and State. Archived from the original on May 17, 2011. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Tumulty, Karen (April 12, 2021b). "Nancy Reagan's Real Role in the AIDS Crisis". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- "40 Years Of Hiv Discovery: The First Cases Of A Mysterious Disease In The Early 1980s". pasteur.fr. Pasteur Institute. May 5, 2023. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- "How HIV Impacts LGBTQ+ People". www.hrc.org. Human Rights Campaign. February 2017. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- "Pat Buchanan's Greatest Hits". The Washington Post. February 3, 1987. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- Weinraub, Bernard (February 6, 1986). "Reagan Orders Aids Report, Giving High Priority To Work For Cure". The New York Times. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- "Snapshots of an Epidemic: An HIV/AIDS Timeline". www.amfar.org. amfAR. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- "US Will Mail AIDS Advisory to All Households". The New York Times. May 5, 1988. Retrieved April 14, 2024.

- "AIDS, the Surgeon General, and the Politics of Public Health". C. Everett Koop - Profiles in Science. March 12, 2019. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- Reagan, Ronald (May 31, 1987). President Reagan's amFAR Speech (Speech). 1987 amFAR Fundraising Dinner. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- Harmon, Leon (December 1, 2015). "Listen to the Reagan Administration Laughing at the AIDS Epidemic". Vice. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- "Ways HIV Can be Transmitted". cdc.gov. Center for Disease Control. March 4, 2022. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- Kaplan, Jonathan E. (December 12, 2022). "Common Myths About HIV and AIDS". WebMD. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- "Interviews - Margaret Heckler - The Age Of Aids - FRONTLINE - PBS". PBS. May 30, 2006.

- Lopez, German (December 1, 2016a). "The Reagan administration's unbelievable response to the HIV/AIDS epidemic". Vox. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- Lawson, Richard (December 1, 2015). "The Reagan Administration's Unearthed Response to the AIDS Crisis Is Chilling". Vanity Fair. Retrieved April 15, 2024.

- Corbett, Meecha (September 9, 2010). "A brief history of AZT". National Museum of American History. Retrieved April 16, 2024.

- "Ronald Reagan Executive Orders - 1987". archives.gov. National Archives. December 7, 2018. Retrieved April 17, 2024.

- "Hudson Has AIDS, Spokesman Says". The New York Times. July 26, 1985. Retrieved November 24, 2016.

- Reagan, Ronald (July 24, 1985). "Wednesday, July 24, 1985". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- Reagan, Ronald (May 31, 1987). "Sunday, May 31, 1987". Ronald Reagan Presidential Foundation and Institute. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- "Report of the Presidential Commission on the Human Immunodeficiency Virus Epidemic" (PDF). www.ojp.gov. June 1988. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- "President Orders Aids Test Notices Those Who Had Blood Transfusions Between 1977 and 1985 Affected". Orlando Sentinel. August 3, 1988. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- Higgins, Bill (July 13, 2019). "Hollywood Flashback: Ronald Reagan Atoned for AIDS Neglect at 1990 Fundraiser". Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- Geidner, Chris (February 2, 2015). "Nancy Reagan Turned Down Rock Hudson's Plea For Help Nine Weeks Before He Died". Buzzfeed News. Retrieved April 19, 2024.

- "Actor's Illness Helped Reagan To Grasp AIDS, Doctor Says". The New York Times. September 2, 1989. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- "President Ronald Reagan's Press Conference in the East Room". catalog.archives.gov. September 17, 1985. Retrieved April 20, 2024.

- Green, Joshua (June 8, 2011). "The Heroic Story of How Congress First Confronted AIDS". The Atlantic. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- "History". oar.nih.gov. August 23, 2022. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- "A plea for more funding". pbs.org. May 30, 2006. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- Boodman, Sandra G. (November 14, 1987). "Caution the Surgeon General of the United States Can Be Hazardous to Your Complacency". Washington Post. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- "A Timeline of HIV and AIDS". hiv.gov. Retrieved April 21, 2024.

- Warren, Jennifer; Paddock, Richard (February 18, 1994). "Randy Shilts, Chronicler of AIDS Epidemic, Dies at 42; Journalism: Author of 'And the Band Played On' is credited with awakening nation to the health crisis". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on March 26, 2022. Retrieved April 22, 2024.

- Brydum, Sunnivie (March 13, 2016). "Bernie Sanders Gets the Reagans' AIDS Legacy Right". The Advocate. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- Lopez, German (March 12, 2016b). "The best explanation for Hillary Clinton's bizarre comments about the Reagans and HIV/AIDS". Vox. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- Mason, James Duke (June 5, 2014). "The Gay Truth About Ronald Reagan". The Advocate. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- Huber, Peter W. (2016). "Ronald Reagan's Quiet War on AIDS". City Journal. Retrieved April 23, 2024.

- Schudel, Matt (December 8, 2018). "Lester Kinsolving, Episcopal priest and pesky White House questioner, dies at 90". Washington Post. Retrieved April 24, 2024.

- "Reagan's Legacy". sfaf.org. February 10, 2011. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- Villarreal, Yezmin (March 11, 2016). "HRC Reminds Hillary Clinton: Nancy Reagan Was 'No Hero' on HIV and AIDS". The Advocate. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- Davis, Wynne (June 9, 2022). "Here's why the new Nancy Reagan stamp prompted backlash from the LGBTQ+ community". NPR. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- Murdock, Deroy (July 28, 2012). "The Gay Left Lies about Reagan — Again". National Review. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- La Ganga, Maria L (March 11, 2016). "The first lady who looked away: Nancy and the Reagans' troubling Aids legacy". The Guardian. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- Harrity, Christopher (March 7, 2016). "Nancy and the Gays". The Advocate. Retrieved April 25, 2024.

- Gibson, Caitlin (December 1, 2015). "A disturbing new glimpse at the Reagan administration's indifference to AIDS". Washington Post. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- "Remarks by Larry Speakes during daily press briefing. (subject: AIDS) White House Press Room". reaganlibrary.gov. June 13, 1983. Retrieved April 26, 2024.

- Fitzsimons, Tim (October 15, 2018). "LGBTQ History Month: The early days of America's AIDS crisis". NBC News. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- Shepard, Robert (October 3, 1985). "House approves millions for AIDS research". United Press International. Retrieved April 30, 2024.

- Percy, William A. (2005). "Percy & Glover 2005". Archived from the original on June 21, 2008. Retrieved April 30, 2024.