Selma Burke

Selma Burke | |

|---|---|

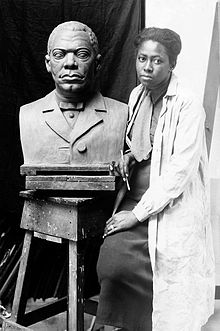

Burke with her portrait bust of Booker T. Washington, c. 1935 | |

| Born | Selma Hortense Burke December 31, 1900 |

| Died | August 29, 1995 (aged 94) |

| Nationality | American |

| Education | Columbia University, Winston-Salem State University |

| Known for | Sculpture |

| Awards | Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award, 1979 |

Selma Hortense Burke (December 31, 1900 – August 29, 1995) was an American sculptor and a member of the Harlem Renaissance movement.[1] Burke is best known for a bas relief portrait of President Franklin D. Roosevelt which may have been the model for his image on the obverse of the dime.[2] She described herself as "a people's sculptor" and created many pieces of public art, often portraits of prominent African-American figures like Duke Ellington, Mary McLeod Bethune and Booker T. Washington.[3][4] In 1979, she was awarded the Women's Caucus for Art Lifetime Achievement Award.[5] She summed up her life as an artist, "I really live and move in the atmosphere in which I am creating".[6]

Biography[edit]

Selma Burke was born on December 31, 1900, in Mooresville, North Carolina, the seventh of 10 children of Reverend Neil and Mary Elizabeth Colfield Burke.[7][8] Her father was an AME Church Minister who worked on the railroads for additional income. Her father died when she was twelve and in 1970 her mother was 101 years old.[6] As a child, she attended a one-room segregated schoolhouse, and often played with the riverbed clay found near her home.[3][9] She would later describe the feeling of squeezing the clay through her fingers as a first encounter with sculpture, saying "It was there in 1907 that I discovered me."[10] Burke's interest in sculpture was encouraged by her maternal grandmother, a painter, although her mother thought she should pursue a more financially stable career.[11] "You can't make a living at that," Burke recalls her mother saying about her desire to study art. [6]

Burke attended Winston-Salem State University before graduating in 1924 from the St. Agnes Training School for Nurses in Raleigh.[12] She married a childhood friend, Durant Woodward, in 1928, although the marriage ended with his death less than a year later.[13] She later moved to Harlem to work as a private nurse.[14][15] She was employed as a private nurse to a wealthy heiress. This heiress later became a patron of Burke and helped her become financially stable during the great depression. [16]

Harlem Renaissance and education[edit]

After moving to New York City in 1935, Burke began art classes at Sarah Lawrence College.[17] She also worked as a model in art classes to pay for that schooling. In 1935, during this time, she also became involved with the Harlem Renaissance cultural movement through her marriage with the writer Claude McKay, with whom she shared an apartment in the Hell's Kitchen neighborhood of Manhattan.[6] The relationship was brief and tumultuous – McKay would destroy her clay models when he did not find the work to be up to his standards – but it introduced Burke to an artistic community that would support her burgeoning career.[18] Burke began teaching for the Harlem Community Arts Center under the leadership of sculptor Augusta Savage, and would go on to work for the Works Progress Administration on the New Deal Federal Art Project.[9] One of her WPA works, a bust of Booker T. Washington, was given to Frederick Douglass High School in Manhattan in 1936.[19]

Burke traveled to Europe twice in the 1930s, first on a Rosenwald fellowship to study sculpture in Vienna in 1933-34. She returned in 1936 to study in Paris with Aristide Maillol. While in Paris she met Henri Matisse, who praised her work.[9] One of her most significant works from this period is "Frau Keller" (1937), a portrait of a German-Jewish woman in response to the rising Nazi threat which would convince Burke to leave Europe later that year.[4] With the onset of World War II, Burke chose to work in a factory as a truck driver for the Brooklyn Navy Yard. It was her opinion that, during the war, "artists should get out of their studios."[20]

After returning to the United States, Burke won a graduate school scholarship to Columbia University, where she would receive a Master of Fine Arts degree in 1941.[20][21]

Teaching and later life[edit]

In 1940 Burke founded the Selma Burke School of Sculpture in New York City.[14] She was committed to teaching art. She opened the Selma Burke Art School in New York City in 1946, and later opened the Selma Burke Art Center in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.[2][22] Open from 1968 to 1981, the center "was an original art center that played an integral role in the Pittsburgh art community," offering courses ranging from studio workshops to puppetry classes.[23]

Burke used her art to make opportunities to bring people together. In Mooresville, black children were banned from use of the public library. With her rising fame, Burke chose to donate a bust of a local doctor on the condition that the ban be removed. The town accepted.[20]

In 1949 Burke married architect Herman Kobbe, and moved with him to an artists' colony in New Hope, Pennsylvania.[9] Kobbe died in 1955, but Burke continued to live in her New Hope home until her death in 1995, at the age of 94.[13]

She taught at Livingstone College, Swarthmore College, and Harvard University, as well as Friends Charter School in Pennsylvania and Harlem Center in New York.[6]

Sculpture[edit]

Selma Burke sculpted portraits of famous African-American figures as well as lesser-known subjects. She also explored human emotion and family relationships in more expressionistic works.[13] While she admired the abstract modernists, her work was more concerned with rendering the symbolic human form in ways both dignified and symbolic.[4] She worked in a wide variety of media including wood, brass, alabaster, and limestone.[24]

Burke's public sculpture pieces include a bust of Duke Ellington at the Performing Arts Center in Milwaukee, as well as works on display at the Hill House Center in Pittsburgh, the Schomburg Center for Research in Black Culture in New York City, Atlanta University, Spelman College, and the Smithsonian Museum of American Art.[25] Her last monumental work, created in 1980 when she was 80 years old, is a bronze statue of Martin Luther King, Jr. in Charlotte, N.C.[3]

Burke was among the artists featured at The National Urban League's inaugural exhibition at Gallery 62 in 1978.[26] She had solo exhibitions at Princeton University and the Carnegie Museum, among other venues. Her work is held in the collections of the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the Whitney Museum of American Art, the Philadelphia Museum of Art,[9] and the James A. Michener Museum of Art in Doylestown, Pennsylvania.

Portrait of F.D.R.[edit]

Burke's best-known work is a portrait honoring President Franklin D. Roosevelt and the Four Freedoms. In 1943, she competed in a national contest to win a commission for the sculpture, created from sketches made during a 45-minute sitting with Roosevelt at the White House.[2] Burke herself "wrote to Roosevelt to request a live sitting, to which the president generously agreed, scheduling the first of two sittings on February 22, 1944."[8] The President died before the third such appointment could be met. His wife Eleanor Roosevelt objected to how young Burke chose to present him, but she responded by saying, "This profile is not for today, but for tomorrow and all time."[20] When asked about her experience sketching the president, "she said he wiggled too much when she began to sketch him that day. She told him to sit still and he did."[27] The 3.5-by-2.5-foot plaque was completed in 1944 and unveiled by President Harry S. Truman in September 1945 at the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington, D.C., where it still hangs today.[23] A number of sources contend that John R. Sinnock's obverse design on the Roosevelt dime was adapted from Burke's plaque[3][4][13][28] even though Sinnock denied that Burke's portrait was an influence, pointing to his earlier work that predated Burke's.[29][30][31] Sinnock's 1933 presidential medal for Roosevelt bears a striking resemblance to the 1946 dime, with Roosevelt facing the opposite direction.[32] Roosevelt's 1941 inaugural medal, which Sinnock was involved in designing, also resembles the 1946 dime.[33] Both the 1933 and 1941 medals predate Burke's bas relief.

- Selected Works

-

Untitled (Woman and Child), 1950

-

Burke, left, presenting her bust of Samuel Huntington (1938) to the principal of Samuel Huntington Junior High School in Jamaica, Queens

-

Bas-relief of Mary Charlton Holiday (1945) at the Iredell County Library, NC.

-

Bust of Mary McLeod Bethune

-

The Franklin Roosevelt plaque in the Recorder of Deeds Building in Washington.

Honors[edit]

Burke is an honorary member of Delta Sigma Theta sorority.[34] She received several honorary doctorate degrees during her lifetime, including one awarded by Livingston College in 1970 and one from Spelman College in 1988.[3][14][35] Milton Shapp, then-governor of Pennsylvania, declared July 29, 1975, Selma Burke Day in recognition of the artist's contributions to art and education.[36] Her papers and archive are in the collection of Spelman College.[13]

Burke was a member of the first group of women – along with Louise Nevelson, Alice Neel, Georgia O'Keeffe, and Isabel Bishop – to receive lifetime achievement awards from the Women's Caucus for Art, in 1979.[37] She received the award from President Jimmy Carter in a private ceremony in the Oval Office.[38][39] She received a Candace Award from the National Coalition of 100 Black Women in 1983, the Pearl S. Buck Foundation Women's Award in 1988, and the Essence Magazine Award in 1989.[40][41][6]

Her work was featured in the 2015 exhibition We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s at the Woodmere Art Museum.[42]

Death[edit]

Selma Burke died at the age of 94 on August 29, 1995, in New Hope, Pennsylvania, where she had lived since the 1950s.[43][44]

References[edit]

- ^ "Burke, Selma". Oxford Reference. Oxford University Press. 2007. doi:10.1093/acref/9780195373219.001.0001. ISBN 9780195373219.

- ^ a b c "Selma Burke; Sculptor, 94". The New York Times. September 2, 1995. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Wallace, Andy (September 1, 1995). "Selma Burke, 94, Black Sculptor Whose Profile Of Fdr Graces Dime". Seattle Times. Retrieved March 4, 2016.

- ^ a b c d Heller, Jules; Heller, Nancy G. (December 19, 2013). North American Women Artists of the Twentieth Century: A Biographical Dictionary. Routledge. ISBN 9781135638825.

- ^ Djossa, Christina Ayele (January 17, 2018). "Who Really Designed the American Dime?". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved September 17, 2018.

- ^ a b c d e f Carney Smith, Jessie (1992). "Selma Hortense Burke". Notable Black American Women. Gale. ISBN 978-0-8103-9177-2.

- ^ Julian, Beatrice (December 1983). "Selma Burke, Dream Shaper". Ebony Jr.: 9 – via Google Books.

- ^ a b Kirschke, Amy Helene, ed. (August 26, 2014). Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. doi:10.14325/mississippi/9781628460339.001.0001. ISBN 9781628460339.

- ^ a b c d e Kort, Carol; Sonneborn, Liz (May 14, 2014). A to Z of American Women in the Visual Arts. Infobase Publishing. ISBN 9781438107912.

- ^ Lewis, Samella S. (2003). African American Art and Artists. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520239357.

- ^ Kirschke, Amy (2014). Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi. p. 119.

- ^ "St. Agnes Hospital School of Nursing | North Carolina Nursing History | Appalachian State University". nursinghistory.appstate.edu. May 2, 2011. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

- ^ a b c d e Ware, Susan (2004). Notable American Women: A Biographical Dictionary Completing the Twentieth Century. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674014886.

- ^ a b c Mack, Felicia (December 15, 2007). "Burke, Selma Hortense (1900-1995)". BlackPast. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ Santandrea, Lisa (January 1, 2001). "Nurses Making a Difference". The American Journal of Nursing. 101 (2): 86–87. doi:10.1097/00000446-200102000-00059. JSTOR 3522121. PMID 11227236.

- ^ "Selma (Hortense) Burke". Contemporary Women Artists. Gale. 1999. ISBN 978-1-55862-372-9.

- ^ Kirschke, Amy Helene (August 4, 2014). Women Artists of the Harlem Renaissance. University Press of Mississippi. ISBN 9781626742079.

- ^ Cooper, Wayne F. (February 1996). Claude McKay, Rebel Sojourner in the Harlem Renaissance: A Biography. LSU Press. ISBN 9780807167298.

- ^ Carr, Eleanor (January 1, 1972). "New York Sculpture during the Federal Project". Art Journal. 31 (4): 397–403. doi:10.2307/775543. JSTOR 775543.

- ^ a b c d Ellin, Nancy (January 1984). "Notable Black Women". Internet Archive. Retrieved March 3, 2020.

- ^ Lewis, David Levering (January 1, 1984). "Parallels and Divergences: Assimilationist Strategies of Afro-American and Jewish Elites from 1910 to the Early 1930s". The Journal of American History. 71 (3): 543–564. doi:10.2307/1887471. JSTOR 1887471.

- ^ Stahl, Joan. "Selma Burke". Smithsonian American Art Museum. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ a b Verderame, Lori. "The Sculptural Legacy Of Selma Burke, 1900-1995". Archived from the original on March 20, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ Gay, Vernon (1983). Discovering Pittsburgh's Sculpture. University of Pittsburgh Press. ISBN 9780822934677.

- ^ "SIRIS - Smithsonian Institution Research Information System". siris-artinventories.si.edu. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Hajosy, Dolores (January 1, 1985). "Gallery 62: An Outlet... A Bridge". Black American Literature Forum. 19 (1): 22–23. doi:10.2307/2904467. JSTOR 2904467.

- ^ “Selma Burke Dead at the Age of 94.” All Things Considered [NPR] (USA), 1995.

- ^ Meschutt, David (January 1, 1986). "Portraits of Franklin Delano Roosevelt". American Art Journal. 18 (4): 3–50. doi:10.2307/1594463. JSTOR 1594463.

- ^ Yanchunas, Dom. "The Roosevelt Dime at 60." COINage Magazine, February 2006.

- ^ "John R. Sinnock, Coin Designer". The Numismatic Scrapbook Magazine: 261. March 15, 1946.

- ^ "Selma Burke, Renowned for FDR Portrait on the Dime". North Carolina Department of Natural and Cultural Resources. December 31, 2016. Retrieved September 18, 2018.

- ^ "FDR medal struck by Mint not official inaugural piece". Coin World. Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Franklin D. Roosevelt Presidential Library and Museum - Inaugural Medal, 1941". Retrieved July 15, 2022.

- ^ "Dr. Selma Burke: A Gifted Artist with Many Accomplishments with". African American Registry. Archived from the original on June 6, 2012. Retrieved December 17, 2011.

- ^ "COLLECTION HIGHLIGHTS - Spelman College Museum of Fine Art". Spelman College Museum of Fine Art. Retrieved October 2, 2017.

- ^ Gumbo Ya Ya: Anthology of Contemporary African-American Women Artists. New York: Midmarch Arts Press. 1995. p. 29.

- ^ Porter, Nancy (January 1, 1979). "Surviving as Women Artists: Two Art History Sessions". Women's Studies Newsletter. 7 (3): 12–14. JSTOR 40042492.

- ^ Halamka, Kathy A. (2007). "Report on the History of the Women's Caucus For Art" (PDF). Cambridge Scholars Press. Archived from the original (PDF) on March 13, 2017. Retrieved March 12, 2017.

- ^ Broude, Norma (January 1, 1979). "Reports on the 67th Annual College Art Association Meeting". Art Journal. 38 (4): 283–285. doi:10.1080/00043249.1979.10793519. JSTOR 776380.

- ^ "Candace Award Recipients 1982–1990, page 1". National Coalition of 100 Black Women. Archived from the original on March 14, 2003.

- ^ Lewis, Samella S. (2003). African American Art and Artists. University of California Press. ISBN 9780520239357.

- ^ "We Speak: Black Artists in Philadelphia, 1920s-1970s". Woodmere Art Museum. Retrieved June 3, 2022.

- ^ "Selma Burke". Encyclopedia.com.

- ^ "Selma Burke; Sculptor, 94". New York Times. September 2, 1995.

Further reading[edit]

- Jones, Frederick N.; Burke, Selma (2007). Out of the miry clay : artistic creativity and spirituality in the making of Selma Burke's art : a study of history, theory/theology, methodology and impact. Columbus, Ga. : Brentwood Christian Press.

- Farrington, Lisa E. (2011). Creating their own image : the history of African-American women artists. Oxford ; New York: Oxford University Press.

External links[edit]

- Entry for Selma Burke on the Union List of Artist Names

- Selma Burke's entry on the African-American Registry

- October Gallery

- Kennedy Center biography of Selma Burke

- Long Island University biography

- 1900 births

- 1995 deaths

- People from Mooresville, North Carolina

- Artists from Pittsburgh

- African-American sculptors

- Sculptors from North Carolina

- Columbia University School of the Arts alumni

- Delta Sigma Theta members

- 20th-century American sculptors

- Federal Art Project artists

- African-American women artists

- Sculptors from Pennsylvania

- 20th-century African-American women

- 20th-century African-American artists

- 20th-century American women sculptors

- African-American women sculptors