Statue of Liberty

| |

|---|---|

The Statue of Liberty in October 2015 | |

| Location | Liberty Island New York City |

| Coordinates | 40°41′21″N 74°2′40″W / 40.68917°N 74.04444°W |

| Height |

|

| Dedicated | October 28, 1886 |

| Restored | 1938, 1984–1986, 2011–2012 |

| Sculptor | Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi |

| Visitors | 3.2 million (in 2009)[1] |

| Governing body | National Park Service |

| Website | www |

| Type | Cultural |

| Criteria | i, vi |

| Designated | 1984 (8th session) |

| Reference no. | 307 |

| Region | Europe and North America |

| Designated | October 15, 1924 |

| Designated by | President Calvin Coolidge[2] |

| Official name | The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World[3][4] |

| Designated | September 14, 2017 |

| Reference no. | 100000829 |

| Official name | Statue of Liberty National Monument, Ellis Island and Liberty Island |

| Designated | May 27, 1971 |

| Reference no. | 1535[5] |

| Designated | June 23, 1980[6] |

| Reference no. | 06101.003324 |

| Type | Individual |

| Designated | September 14, 1976[7] |

| Reference no. | 0931 |

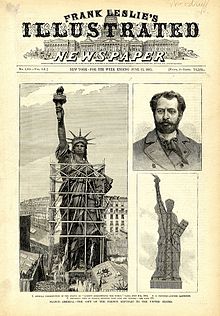

The Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World; French: La Liberté éclairant le monde) is a colossal neoclassical sculpture on Liberty Island in New York Harbor in New York City, United States. The copper statue, a gift from the people of France, was designed by French sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi and its metal framework was built by Gustave Eiffel. The statue was dedicated on October 28, 1886.

The statue is a figure of Libertas, the Roman goddess of liberty. She holds a torch above her head with her right hand, and in her left hand carries a tabula ansata inscribed JULY IV MDCCLXXVI (July 4, 1776, in Roman numerals), the date of the U.S. Declaration of Independence. A broken chain and shackle lie at her feet as she walks forward, commemorating the national abolition of slavery following the American Civil War.[8] After its dedication the statue became an icon of freedom and of the United States, being subsequently seen as a symbol of welcome to immigrants arriving by sea.

The idea for the statue was born in 1865, when the French historian and abolitionist Édouard de Laboulaye proposed a monument to commemorate the upcoming centennial of U.S. independence (1876), the perseverance of American democracy and the liberation of the nation's slaves.[9] The Franco-Prussian War delayed progress until 1875, when Laboulaye proposed that the people of France finance the statue and the United States provide the site and build the pedestal. Bartholdi completed the head and the torch-bearing arm before the statue was fully designed, and these pieces were exhibited for publicity at international expositions.

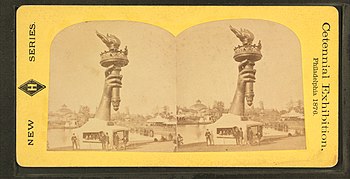

The torch-bearing arm was displayed at the Centennial Exposition in Philadelphia in 1876, and in Madison Square Park in Manhattan from 1876 to 1882. Fundraising proved difficult, especially for the Americans, and by 1885 work on the pedestal was threatened by lack of funds. Publisher Joseph Pulitzer, of the New York World, started a drive for donations to finish the project and attracted more than 120,000 contributors, most of whom gave less than a dollar (equivalent to $34 in 2023). The statue was built in France, shipped overseas in crates, and assembled on the completed pedestal on what was then called Bedloe's Island. The statue's completion was marked by New York's first ticker-tape parade and a dedication ceremony presided over by President Grover Cleveland.

The statue was administered by the United States Lighthouse Board until 1901 and then by the Department of War; since 1933, it has been maintained by the National Park Service as part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument, and is a major tourist attraction. Limited numbers of visitors can access the rim of the pedestal and the interior of the statue's crown from within; public access to the torch has been barred since 1916.

Design and construction process

Origin

According to the National Park Service, the idea of a monument presented by the French people to the United States was first proposed by Édouard René de Laboulaye, president of the French Anti-Slavery Society and a prominent and important political thinker of his time. The project is traced to a mid-1865 conversation between Laboulaye, a staunch abolitionist, and Frédéric Bartholdi, a sculptor. In after-dinner conversation at his home near Versailles, Laboulaye, an ardent supporter of the Union in the American Civil War, is supposed to have said: "If a monument should rise in the United States, as a memorial to their independence, I should think it only natural if it were built by united effort—a common work of both our nations."[10] The National Park Service, in a 2000 report, however, deemed this a legend traced to an 1885 fundraising pamphlet, and that the statue was most likely conceived in 1870.[11] In another essay on their website, the Park Service suggested that Laboulaye was minded to honor the Union victory and its consequences, "With the abolition of slavery and the Union's victory in the Civil War in 1865, Laboulaye's wishes of freedom and democracy were turning into a reality in the United States. In order to honor these achievements, Laboulaye proposed that a gift be built for the United States on behalf of France. Laboulaye hoped that by calling attention to the recent achievements of the United States, the French people would be inspired to call for their own democracy in the face of a repressive monarchy."[12]

According to sculptor Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi, who later recounted the story, Laboulaye's alleged comment was not intended as a proposal, but it inspired Bartholdi.[10] Given the repressive nature of the regime of Napoleon III, Bartholdi took no immediate action on the idea except to discuss it with Laboulaye. Bartholdi was in any event busy with other possible projects; in the late 1860s, he approached Isma'il Pasha, Khedive of Egypt, with a plan to build Progress or Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia,[13] a huge lighthouse in the form of an ancient Egyptian female fellah or peasant, robed and holding a torch aloft, at the northern entrance to the Suez Canal in Port Said. Sketches and models were made of the proposed work, though it was never erected. There was a classical precedent for the Suez proposal, the Colossus of Rhodes: an ancient bronze statue of the Greek god of the sun, Helios. This statue is believed to have been over 100 feet (30 m) high, and it similarly stood at a harbor entrance and carried a light to guide ships.[14] Both the khedive and Ferdinand de Lesseps, developer of the Suez Canal, declined the proposed statue from Bartholdi, citing the high cost.[15] The Port Said Lighthouse was built instead, by François Coignet in 1869.

Any large project was further delayed by the Franco-Prussian War, in which Bartholdi served as a major of militia. In the war, Napoleon III was captured and deposed. Bartholdi's home province of Alsace was lost to the Prussians, and a more liberal republic was installed in France.[10] As Bartholdi had been planning a trip to the United States, he and Laboulaye decided the time was right to discuss the idea with influential Americans.[16] In June 1871, Bartholdi crossed the Atlantic, with letters of introduction signed by Laboulaye.[17]

Arriving at New York Harbor, Bartholdi focused on Bedloe's Island (now named Liberty Island) as a site for the statue, struck by the fact that vessels arriving in New York had to sail past it. He was delighted to learn that the island was owned by the United States government—it had been ceded by the New York State Legislature in 1800 for harbor defense. It was thus, as he put it in a letter to Laboulaye: "land common to all the states."[18] As well as meeting many influential New Yorkers, Bartholdi visited President Ulysses S. Grant, who assured him that it would not be difficult to obtain the site for the statue.[19] Bartholdi crossed the United States twice by rail, and met many Americans who he thought would be sympathetic to the project.[17] But he remained concerned that popular opinion on both sides of the Atlantic was insufficiently supportive of the proposal, and he and Laboulaye decided to wait before mounting a public campaign.[20]

Bartholdi had made a first model of his concept in 1870.[21] The son of a friend of Bartholdi's, artist John LaFarge, later maintained that Bartholdi made the first sketches for the statue during his visit to La Farge's Rhode Island studio. Bartholdi continued to develop the concept following his return to France.[21] He also worked on a number of sculptures designed to bolster French patriotism after the defeat by the Prussians. One of these was the Lion of Belfort, a monumental sculpture carved in sandstone below the fortress of Belfort, which during the war had resisted a Prussian siege for over three months. The defiant lion, 73 feet (22 m) long and half that in height, displays an emotional quality characteristic of Romanticism, which Bartholdi would later bring to the Statue of Liberty.[22]

Design, style, and symbolism

Bartholdi and Laboulaye considered how best to express the idea of American liberty.[23] In early American history, two female figures were frequently used as cultural symbols of the nation.[24] One of these symbols, the personified Columbia, was seen as an embodiment of the United States in the manner that Britannia was identified with the United Kingdom, and Marianne came to represent France. Columbia had supplanted the traditional European Personification of the Americas as an "Indian princess", which had come to be regarded as uncivilized and derogatory toward Americans.[24] The other significant female icon in American culture was a representation of Liberty, derived from Libertas, the goddess of freedom widely worshipped in ancient Rome, especially among emancipated slaves. A Liberty figure adorned most American coins of the time,[23] and representations of Liberty appeared in popular and civic art, including Thomas Crawford's Statue of Freedom (1863) atop the dome of the United States Capitol Building.[23]

The statue's design evokes iconography evident in ancient history including the Egyptian goddess Isis, the ancient Greek deity of the same name, the Roman Columbia and the Christian iconography of the Virgin Mary.[25][26]

Artists of the 18th and 19th centuries striving to evoke republican ideals commonly used representations of Libertas as an allegorical symbol.[23] A figure of Liberty was also depicted on the Great Seal of France.[23] However, Bartholdi and Laboulaye avoided an image of revolutionary liberty such as that depicted in Eugène Delacroix's famed Liberty Leading the People (1830). In this painting, which commemorates France's July Revolution, a half-clothed Liberty leads an armed mob over the bodies of the fallen.[24] Laboulaye had no sympathy for revolution, and so Bartholdi's figure would be fully dressed in flowing robes.[24] Instead of the impression of violence in the Delacroix work, Bartholdi wished to give the statue a peaceful appearance and chose a torch, representing progress, for the figure to hold.[27] Its second toe on both feet is longer than its big toe, a condition known as Morton's toe or 'Greek foot'. This was an aesthetic staple of ancient Greek art and reflects the classical influences on the statue.[28]

Crawford's statue was designed in the early 1850s. It was originally to be crowned with a pileus, the cap given to emancipated slaves in ancient Rome. Secretary of War Jefferson Davis, a Southerner who would later serve as President of the Confederate States of America, was concerned that the pileus would be taken as an abolitionist symbol. He ordered that it be changed to a helmet.[29] Delacroix's figure wears a pileus,[24] and Bartholdi at first considered placing one on his figure as well. Instead, he used a radiate diadem, or crown, to top its head.[30] In so doing, he avoided a reference to Marianne, who invariably wears a pileus.[31] The seven rays form a halo or aureole.[32] They evoke the sun, the seven seas, and the seven continents,[33] and represent another means, besides the torch, whereby Liberty enlightens the world.[27]

Bartholdi's early models were all similar in concept: a female figure in neoclassical style representing liberty, wearing a stola and pella (gown and cloak, common in depictions of Roman goddesses) and holding a torch aloft. According to popular accounts, the face was modeled after that of Charlotte Beysser Bartholdi, the sculptor's mother,[34] but Regis Huber, the curator of the Bartholdi Museum is on record as saying that this, as well as other similar speculations, have no basis in fact.[35] He designed the figure with a strong, uncomplicated silhouette, which would be set off well by its dramatic harbor placement and allow passengers on vessels entering New York Bay to experience a changing perspective on the statue as they proceeded toward Manhattan. He gave it bold classical contours and applied simplified modeling, reflecting the huge scale of the project and its solemn purpose.[27] Bartholdi wrote of his technique:

The surfaces should be broad and simple, defined by a bold and clear design, accentuated in the important places. The enlargement of the details or their multiplicity is to be feared. By exaggerating the forms, in order to render them more clearly visible, or by enriching them with details, we would destroy the proportion of the work. Finally, the model, like the design, should have a summarized character, such as one would give to a rapid sketch. Only it is necessary that this character should be the product of volition and study, and that the artist, concentrating his knowledge, should find the form and the line in its greatest simplicity.[36]

Bartholdi made alterations in the design as the project evolved. Bartholdi considered having Liberty hold a broken chain, but decided this would be too divisive in the days after the Civil War. The erected statue does stride over a broken chain, half-hidden by her robes and difficult to see from the ground.[30] Bartholdi was initially uncertain of what to place in Liberty's left hand; he settled on a tabula ansata,[37] used to evoke the concept of law.[38] Though Bartholdi greatly admired the United States Constitution, he chose to inscribe JULY IV MDCCLXXVI on the tablet, thus associating the date of the country's Declaration of Independence with the concept of liberty.[37]

Bartholdi interested his friend and mentor, architect Eugène Viollet-le-Duc, in the project.[35] As chief engineer,[35] Viollet-le-Duc designed a brick pier within the statue, to which the skin would be anchored.[39] After consultations with the metalwork foundry Gaget, Gauthier & Co., Viollet-le-Duc chose the metal which would be used for the skin, copper sheets, and the method used to shape it, repoussé, in which the sheets were heated and then struck with wooden hammers.[35][40] An advantage of this choice was that the entire statue would be light for its volume, as the copper need be only 0.094 inches (2.4 mm) thick. Bartholdi had decided on a height of just over 151 feet (46 m) for the statue, double that of Italy's Sancarlone and the German statue of Arminius, both made with the same method.[41]

Announcement and early work

By 1875, France was enjoying improved political stability and a recovering postwar economy. Growing interest in the upcoming Centennial Exposition to be held in Philadelphia led Laboulaye to decide it was time to seek public support.[42] In September 1875, he announced the project and the formation of the Franco-American Union as its fundraising arm. With the announcement, the statue was given a name, Liberty Enlightening the World.[43] The French would finance the statue; Americans would be expected to pay for the pedestal.[44] The announcement provoked a generally favorable reaction in France, though many Frenchmen resented the United States for not coming to their aid during the war with Prussia.[43] French monarchists opposed the statue, if for no other reason than it was proposed by the liberal Laboulaye, who had recently been elected a senator for life.[44] Laboulaye arranged events designed to appeal to the rich and powerful, including a special performance at the Paris Opera on April 25, 1876, that featured a new cantata by the composer Charles Gounod. The piece was titled La Liberté éclairant le monde, the French version of the statue's announced name.[43]

Initially focused on the elites, the Union was successful in raising funds from across French society. Schoolchildren and ordinary citizens gave, as did 181 French municipalities. Laboulaye's political allies supported the call, as did descendants of the French contingent in the American Revolutionary War. Less idealistically, contributions came from those who hoped for American support in the French attempt to build the Panama Canal. The copper may have come from multiple sources and some of it is said to have come from a mine in Visnes, Norway,[45] though this has not been conclusively determined after testing samples.[46] According to Cara Sutherland in her book on the statue for the Museum of the City of New York, 200,000 pounds (91,000 kg) was needed to build the statue, and the French copper industrialist Eugène Secrétan donated 128,000 pounds (58,000 kg) of copper.[47]

Although plans for the statue had not been finalized, Bartholdi moved forward with fabrication of the right arm, bearing the torch, and the head. Work began at the Gaget, Gauthier & Co. workshop.[48] In May 1876, Bartholdi traveled to the United States as a member of a French delegation to the Centennial Exhibition,[49] and arranged for a huge painting of the statue to be shown in New York as part of the Centennial festivities.[50] The arm did not arrive in Philadelphia until August; because of its late arrival, it was not listed in the exhibition catalogue, and while some reports correctly identified the work, others called it the "Colossal Arm" or "Bartholdi Electric Light". The exhibition grounds contained a number of monumental artworks to compete for fairgoers' interest, including an outsized fountain designed by Bartholdi.[51] Nevertheless, the arm proved popular in the exhibition's waning days, and visitors would climb up to the balcony of the torch to view the fairgrounds.[52] After the exhibition closed, the arm was transported to New York City, where it remained on display in Madison Square Park for several years before it was returned to France to join the rest of the statue.[52]

During his second trip to the United States, Bartholdi addressed a number of groups about the project, and urged the formation of American committees of the Franco-American Union.[53] Committees to raise money to pay for the foundation and pedestal were formed in New York, Boston, and Philadelphia.[54] The New York group eventually took on most of the responsibility for American fundraising and is often referred to as the "American Committee".[55] One of its members was 19-year-old Theodore Roosevelt, the future governor of New York and president of the United States.[53] On March 3, 1877, on his final full day in office, President Grant signed a joint resolution that authorized the President to accept the statue when it was presented by France and to select a site for it. President Rutherford B. Hayes, who took office the following day, selected the Bedloe's Island site that Bartholdi had proposed.[56]

Construction in France

On his return to Paris in 1877, Bartholdi concentrated on completing the head, which was exhibited at the 1878 Paris World's Fair. Fundraising continued, with models of the statue put on sale. Tickets to view the construction activity at the Gaget, Gauthier & Co. workshop were also offered.[57] The French government authorized a lottery; among the prizes were valuable silver plate and a terracotta model of the statue. By the end of 1879, about 250,000 francs had been raised.[58]

The head and arm had been built with assistance from Viollet-le-Duc, who fell ill in 1879. He soon died, leaving no indication of how he intended to transition from the copper skin to his proposed masonry pier.[59] The following year, Bartholdi was able to obtain the services of the innovative designer and builder Gustave Eiffel.[57] Eiffel and his structural engineer, Maurice Koechlin, decided to abandon the pier and instead build an iron truss tower. Eiffel opted not to use a completely rigid structure, which would force stresses to accumulate in the skin and lead eventually to cracking. A secondary skeleton was attached to the center pylon, then, to enable the statue to move slightly in the winds of New York Harbor and as the metal expanded on hot summer days, he loosely connected the support structure to the skin using flat iron bars[35] which culminated in a mesh of metal straps, known as "saddles", that were riveted to the skin, providing firm support. In a labor-intensive process, each saddle had to be crafted individually.[60][61] To prevent galvanic corrosion between the copper skin and the iron support structure, Eiffel insulated the skin with asbestos impregnated with shellac.[62]

Eiffel's design made the statue one of the earliest examples of curtain wall construction, in which the exterior of the structure is not load bearing, but is instead supported by an interior framework. He included two interior spiral staircases, to make it easier for visitors to reach the observation point in the crown.[63] Access to an observation platform surrounding the torch was also provided, but the narrowness of the arm allowed for only a single ladder, 40 feet (12 m) long.[64] As the pylon tower arose, Eiffel and Bartholdi coordinated their work carefully so that completed segments of skin would fit exactly on the support structure.[65] The components of the pylon tower were built in the Eiffel factory in the nearby Parisian suburb of Levallois-Perret.[66]

The change in structural material from masonry to iron allowed Bartholdi to change his plans for the statue's assembly. He had originally expected to assemble the skin on-site as the masonry pier was built; instead, he decided to build the statue in France and have it disassembled and transported to the United States for reassembly in place on Bedloe's Island.[67]

In a symbolic act, the first rivet placed into the skin, fixing a copper plate onto the statue's big toe, was driven by United States Ambassador to France Levi P. Morton.[68] The skin was not, however, crafted in exact sequence from low to high; work proceeded on a number of segments simultaneously in a manner often confusing to visitors.[69] Some work was performed by contractors—one of the fingers was made to Bartholdi's exacting specifications by a coppersmith in the southern French town of Montauban.[70] By 1882, the statue was complete up to the waist, an event Barthodi celebrated by inviting reporters to lunch on a platform built within the statue.[71] Laboulaye died in 1883. He was succeeded as chairman of the French committee by Lesseps. The completed statue was formally presented to Ambassador Morton at a ceremony in Paris on July 4, 1884, and Lesseps announced that the French government had agreed to pay for its transport to New York.[72] The statue remained intact in Paris pending sufficient progress on the pedestal; by January 1885, this had occurred and the statue was disassembled and crated for its ocean voyage.[73]

The committees in the United States faced great difficulties in obtaining funds for the construction of the pedestal. The Panic of 1873 had led to an economic depression that persisted through much of the decade. The Liberty statue project was not the only such undertaking that had difficulty raising money: construction of the obelisk later known as the Washington Monument sometimes stalled for years; it would ultimately take over three-and-a-half decades to complete.[74] There was criticism both of Bartholdi's statue and of the fact that the gift required Americans to foot the bill for the pedestal. In the years following the Civil War, most Americans preferred realistic artworks depicting heroes and events from the nation's history, rather than allegorical works like the Liberty statue.[74] There was also a feeling that Americans should design American public works—the selection of Italian-born Constantino Brumidi to decorate the Capitol had provoked intense criticism, even though he was a naturalized U.S. citizen.[75] Harper's Weekly declared its wish that "M. Bartholdi and our French cousins had 'gone the whole figure' while they were about it, and given us statue and pedestal at once."[76] The New York Times stated that "no true patriot can countenance any such expenditures for bronze females in the present state of our finances."[77] Faced with these criticisms, the American committees took little action for several years.[77]

Design

The foundation of Bartholdi's statue was to be laid inside Fort Wood, a disused army base on Bedloe's Island constructed between 1807 and 1811. Since 1823, it had rarely been used, though during the Civil War, it had served as a recruiting station.[78] The fortifications of the structure were in the shape of an eleven-point star. The statue's foundation and pedestal were aligned so that it would face southeast, greeting ships entering the harbor from the Atlantic Ocean.[79] In 1881, the New York committee commissioned Richard Morris Hunt to design the pedestal. Within months, Hunt submitted a detailed plan, indicating that he expected construction to take about nine months.[80] He proposed a pedestal 114 feet (35 m) in height; faced with money problems, the committee reduced that to 89 feet (27 m).[81]

Hunt's pedestal design contains elements of classical architecture, including Doric portals, as well as some elements influenced by Aztec architecture.[35] The large mass is fragmented with architectural detail, in order to focus attention on the statue.[81] In form, it is a truncated pyramid, 62 feet (19 m) square at the base and 39.4 feet (12.0 m) at the top. The four sides are identical in appearance. Above the door on each side, there are ten disks upon which Bartholdi proposed to place the coats of arms of the states (between 1876 and 1889, there were 38 of them), although this was not done. Above that, a balcony was placed on each side, framed by pillars. Bartholdi placed an observation platform near the top of the pedestal, above which the statue itself rises.[82] According to author Louis Auchincloss, the pedestal "craggily evokes the power of an ancient Europe over which rises the dominating figure of the Statue of Liberty".[81] The committee hired former army General Charles Pomeroy Stone to oversee the construction work.[83] Construction on the 15-foot-deep (4.6 m) foundation began in 1883, and the pedestal's cornerstone was laid in 1884.[80] In Hunt's original conception, the pedestal was to have been made of solid granite. Financial concerns again forced him to revise his plans; the final design called for poured concrete walls, up to 20 feet (6.1 m) thick, faced with granite blocks.[84][85] This Stony Creek granite came from the Beattie Quarry in Branford, Connecticut.[86] The concrete mass was the largest poured to that time.[85]

Norwegian immigrant civil engineer Joachim Goschen Giæver designed the structural framework for the Statue of Liberty. His work involved design computations, detailed fabrication and construction drawings, and oversight of construction. In completing his engineering for the statue's frame, Giæver worked from drawings and sketches produced by Gustave Eiffel.[87]

Fundraising

Fundraising in the U.S. for the pedestal had begun in 1882. The committee organized a large number of money-raising events.[88] As part of one such effort, an auction of art and manuscripts, poet Emma Lazarus was asked to donate an original work. She initially declined, stating she could not write a poem about a statue. At the time, she was also involved in aiding refugees to New York who had fled antisemitic pogroms in eastern Europe. These refugees were forced to live in conditions that the wealthy Lazarus had never experienced. She saw a way to express her empathy for these refugees in terms of the statue.[89] The resulting sonnet, "The New Colossus", including the lines "Give me your tired, your poor/Your huddled masses yearning to breathe free", is uniquely identified with the Statue of Liberty in American culture and is inscribed on a plaque in its museum.[90]

Even with these efforts, fundraising lagged. Grover Cleveland, the governor of New York, vetoed a bill to provide $50,000 for the statue project in 1884. An attempt the next year to have Congress provide $100,000, sufficient to complete the project, also failed. The New York committee, with only $3,000 in the bank, suspended work on the pedestal. With the project in jeopardy, groups from other American cities, including Boston and Philadelphia, offered to pay the full cost of erecting the statue in return for relocating it.[92]

Joseph Pulitzer, publisher of the New York World, a New York newspaper, announced a drive to raise $100,000 (equivalent to $3,391,000 in 2023). Pulitzer pledged to print the name of every contributor, no matter how small the amount given.[93] The drive captured the imagination of New Yorkers, especially when Pulitzer began publishing the notes he received from contributors. "A young girl alone in the world" donated "60 cents, the result of self denial."[94] One donor gave "five cents as a poor office boy's mite toward the Pedestal Fund." A group of children sent a dollar as "the money we saved to go to the circus with."[95] Another dollar was given by a "lonely and very aged woman."[94] Residents of a home for alcoholics in New York's rival city of Brooklyn—the cities would not merge until 1898—donated $15; other drinkers helped out through donation boxes in bars and saloons.[96] A kindergarten class in Davenport, Iowa, mailed the World a gift of $1.35.[94] As the donations flooded in, the committee resumed work on the pedestal.[97] France raised about $250,000 to build the statue,[98] while the United States had to raise up to $300,000 to build the pedestal.[99][100]

Construction

On June 17, 1885, the French steamer Isère arrived in New York with the crates holding the disassembled statue on board. New Yorkers displayed their newfound enthusiasm for the statue. Two hundred thousand people lined the docks and hundreds of boats put to sea to welcome the ship.[101][102] After five months of daily calls to donate to the statue fund, on August 11, 1885, the World announced that $102,000 had been raised from 120,000 donors, and that 80 percent of the total had been received in sums of less than one dollar (equivalent to $34 in 2023).[103]

Even with the success of the fund drive, the pedestal was not completed until April 1886. Immediately thereafter, reassembly of the statue began. Eiffel's iron framework was anchored to steel I-beams within the concrete pedestal and assembled.[104] Once this was done, the sections of skin were carefully attached.[105] Due to the width of the pedestal, it was not possible to erect scaffolding, and workers dangled from ropes while installing the skin sections.[106] Bartholdi had planned to put floodlights on the torch's balcony to illuminate it; a week before the dedication, the Army Corps of Engineers vetoed the proposal, fearing that ships' pilots passing the statue would be blinded. Instead, Bartholdi cut portholes in the torch—which was covered with gold leaf—and placed the lights inside them.[107] A power plant was installed on the island to light the torch and for other electrical needs.[108] After the skin was completed, landscape architect Frederick Law Olmsted, co-designer of Manhattan's Central Park and Brooklyn's Prospect Park, supervised a cleanup of Bedloe's Island in anticipation of the dedication.[109] General Charles Stone claimed on the day of dedication that no man had died during the construction of the statue. This was not true, however, as Francis Longo, a thirty-nine-year-old Italian laborer, had been killed when an old wall fell on him.[110] According to Reader's Digest, the copper’s shiny metallic surface began oxidizing upon assembly, quickly turning the exterior into a dark brown mineral coating called tenorite. This tenorite and oxidized copper then mixed with the sulfuric acid in the air to create the green color seen today.[111]

Dedication

A ceremony of dedication was held on the afternoon of October 28, 1886. President Grover Cleveland, the former New York governor, presided over the event.[112] On the morning of the dedication, a parade was held in New York City; estimates of the number of people who watched it ranged from several hundred thousand to a million. President Cleveland headed the procession, then stood in the reviewing stand to see bands and marchers from across America. General Stone was the grand marshal of the parade. The route began at Madison Square, once the venue for the arm, and proceeded to the Battery at the southern tip of Manhattan by way of Fifth Avenue and Broadway, with a slight detour so the parade could pass in front of the World building on Park Row. As the parade passed the New York Stock Exchange, traders threw ticker tape from the windows, beginning the New York tradition of the ticker-tape parade.[113]

A nautical parade began at 12:45 p.m., and President Cleveland embarked on a yacht that took him across the harbor to Bedloe's Island for the dedication.[114] Lesseps made the first speech, on behalf of the French committee, followed by the chairman of the New York committee, Senator William M. Evarts. A French flag draped across the statue's face was to be lowered to unveil the statue at the close of Evarts's speech, but Bartholdi mistook a pause as the conclusion and let the flag fall prematurely. The ensuing cheers put an end to Evarts's address.[113] President Cleveland spoke next, stating that the statue's "stream of light shall pierce the darkness of ignorance and man's oppression until Liberty enlightens the world".[115] Bartholdi, observed near the dais, was called upon to speak, but he declined. Orator Chauncey M. Depew concluded the speechmaking with a lengthy address.[116]

No members of the general public were permitted on the island during the ceremonies, which were reserved entirely for dignitaries. The only women granted access were Bartholdi's wife and Lesseps's granddaughter; officials stated that they feared women might be injured in the crush of people. The restriction offended area suffragists, who chartered a boat and got as close as they could to the island. The group's leaders made speeches applauding the embodiment of Liberty as a woman and advocating women's right to vote.[115] A scheduled fireworks display was postponed until November 1 because of poor weather.[117]

Shortly after the dedication, The Cleveland Gazette, an African American newspaper, suggested that the statue's torch not be lit until the United States became a free nation "in reality":

"Liberty enlightening the world," indeed! The expression makes us sick. This government is a howling farce. It can not or rather does not protect its citizens within its own borders. Shove the Bartholdi statue, torch and all, into the ocean until the "liberty" of this country is such as to make it possible for an inoffensive and industrious colored man to earn a respectable living for himself and family, without being ku-kluxed, perhaps murdered, his daughter and wife outraged, and his property destroyed. The idea of the "liberty" of this country "enlightening the world," or even Patagonia, is ridiculous in the extreme.[118]

After dedication

Lighthouse Board and War Department (1886–1933)

When the torch was illuminated on the evening of the statue's dedication, it produced only a faint gleam, barely visible from Manhattan. The World characterized it as "more like a glowworm than a beacon."[108] Bartholdi suggested gilding the statue to increase its ability to reflect light, but this proved too expensive. The United States Lighthouse Board took over the Statue of Liberty in 1887 and pledged to install equipment to enhance the torch's effect; in spite of its efforts, the statue remained virtually invisible at night. When Bartholdi returned to the United States in 1893, he made additional suggestions, all of which proved ineffective. He did successfully lobby for improved lighting within the statue, allowing visitors to better appreciate Eiffel's design.[108] In 1901, President Theodore Roosevelt, once a member of the New York committee, ordered the statue's transfer to the War Department, as it had proved useless as a lighthouse.[119] A unit of the Army Signal Corps was stationed on Bedloe's Island until 1923, after which military police remained there while the island was under military jurisdiction.[120]

Wars and other upheavals in Europe prompted large-scale emigration to the United States in the late 19th and early 20th century; many entered through New York and saw the statue not as a symbol of enlightenment, as Bartholdi had intended, but as a sign of welcome to their new home. The association with immigration only became stronger when an immigrant processing station was opened on nearby Ellis Island. This view was consistent with Lazarus's vision in her sonnet—she described the statue as "Mother of Exiles"—but her work had become obscure. In 1903, the sonnet was engraved on a plaque that was affixed to the base of the statue.[121]

Oral histories of immigrants record their feelings of exhilaration on first viewing the Statue of Liberty. One immigrant who arrived from Greece recalled:

I saw the Statue of Liberty. And I said to myself, "Lady, you're such a beautiful! [sic] You opened your arms and you get all the foreigners here. Give me a chance to prove that I am worth it, to do something, to be someone in America." And always that statue was on my mind.[122]

The statue rapidly became a landmark.[122] Originally, it was a dull copper color, but shortly after 1900 a green patina, also called verdigris, caused by the oxidation of the copper skin, began to spread. As early as 1902 it was mentioned in the press; by 1906 it had entirely covered the statue.[123] Believing that the patina was evidence of corrosion, Congress authorized US$62,800 (equivalent to $2,130,000 in 2023) for various repairs, and to paint the statue both inside and out.[124] There was considerable public protest against the proposed exterior painting.[125] The Army Corps of Engineers studied the patina for any ill effects to the statue and concluded that it protected the skin, "softened the outlines of the Statue and made it beautiful."[126] The statue was painted only on the inside. The Corps of Engineers also installed an elevator to take visitors from the base to the top of the pedestal.[126]

On July 30, 1916, during World War I, German saboteurs set off a disastrous explosion on the Black Tom peninsula in Jersey City, New Jersey, in what is now part of Liberty State Park, close to Bedloe's Island. Carloads of dynamite and other explosives that were being sent to Russia[127] for its war efforts were detonated. The statue sustained minor damage, mostly to the torch-bearing right arm, and was closed for ten days. The cost to repair the statue and buildings on the island was about $100,000 (equivalent to about $2,800,000 in 2023). The narrow ascent to the torch was closed for public-safety reasons, and it has remained closed ever since.[116]

That same year, Ralph Pulitzer, who had succeeded his father Joseph as publisher of the World, began a drive to raise $30,000 (equivalent to $840,000 in 2023) for an exterior lighting system to illuminate the statue at night. He claimed over 80,000 contributors, but failed to reach the goal. The difference was quietly made up by a gift from a wealthy donor—a fact that was not revealed until 1936. An underwater power cable brought electricity from the mainland and floodlights were placed along the walls of Fort Wood. Gutzon Borglum, who later sculpted Mount Rushmore, redesigned the torch, replacing much of the original copper with stained glass. On December 2, 1916, President Woodrow Wilson pressed the telegraph key that turned on the lights, successfully illuminating the statue.[128]

After the United States entered World War I in 1917, images of the statue were heavily used in both recruitment posters and the Liberty bond drives that urged American citizens to support the war financially. This impressed upon the public the war's stated purpose—to secure liberty—and served as a reminder that embattled France had given the United States the statue.[129]

In 1924, President Calvin Coolidge used his authority under the Antiquities Act to declare the statue a national monument.[119] A suicide occurred five years later when a man climbed out of one of the windows in the crown and jumped to his death.[130]

Early National Park Service years (1933–1982)

In 1933, President Franklin Roosevelt ordered the statue to be transferred to the National Park Service (NPS). In 1937, the NPS gained jurisdiction over the rest of Bedloe's Island.[119] With the Army's departure, the NPS began to transform the island into a park.[131] The Works Progress Administration (WPA) demolished most of the old buildings, regraded and reseeded the eastern end of the island, and built granite steps for a new public entrance to the statue from its rear. The WPA also carried out restoration work within the statue, temporarily removing the rays from the statue's halo so their rusted supports could be replaced. Rusted cast-iron steps in the pedestal were replaced with new ones made of reinforced concrete;[132] the upper parts of the stairways within the statue were replaced, as well. Copper sheathing was installed to prevent further damage from rainwater that had been seeping into the pedestal.[133] The statue was closed to the public from May until December 1938.[132]

During World War II, the statue remained open to visitors, although it was not illuminated at night due to wartime blackouts. It was lit briefly on December 31, 1943, and on D-Day, June 6, 1944, when its lights flashed "dot-dot-dot-dash", the Morse code for V, for victory. New, powerful lighting was installed in 1944–1945, and beginning on V-E Day, the statue was once again illuminated after sunset. The lighting was for only a few hours each evening, and it was not until 1957 that the statue was illuminated every night, all night.[134] In 1946, the interior of the statue within reach of visitors was coated with a special plastic so that graffiti could be washed away.[133]

In 1956, an Act of Congress officially renamed Bedloe's Island as Liberty Island, a change advocated by Bartholdi generations earlier. The act also mentioned the efforts to found an American Museum of Immigration on the island, which backers took as federal approval of the project, though the government was slow to grant funds for it.[135] Nearby Ellis Island was made part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument by proclamation of President Lyndon Johnson in 1965.[119] In 1972, the immigration museum, in the statue's base, was finally opened in a ceremony led by President Richard Nixon. The museum's backers never provided it with an endowment to secure its future and it closed in 1991 after the opening of an immigration museum on Ellis Island.[104]

In 1970, Ivy Bottini led a demonstration at the statue where she and others from the National Organization for Women's New York chapter draped an enormous banner over a railing which read "WOMEN OF THE WORLD UNITE!"[136][137]

Beginning December 26, 1971, 15 anti-Vietnam War veterans occupied the statue, flying a US flag upside down from her crown. They left December 28 following a federal court order.[138] The statue was also several times taken over briefly by demonstrators publicizing causes such as Puerto Rican independence, opposition to abortion, and opposition to US intervention in Grenada. Demonstrations with the permission of the Park Service included a Gay Pride Parade rally and the annual Captive Baltic Nations rally.[139]

A powerful new lighting system was installed in advance of the American Bicentennial in 1976. The statue was the focal point for Operation Sail, a regatta of tall ships from all over the world that entered New York Harbor on July 4, 1976, and sailed around Liberty Island.[140] The day concluded with a spectacular display of fireworks near the statue.[141]

Renovation and rededication (1982–2000)

The statue was examined in great detail by French and American engineers as part of the planning for its centennial in 1986.[142] In 1982, it was announced that the statue was in need of considerable restoration. Careful study had revealed that the right arm had been improperly attached to the main structure. It was swaying more and more when strong winds blew and there was a significant risk of structural failure. In addition, the head had been installed 2 feet (0.61 m) off center, and one of the rays was wearing a hole in the right arm when the statue moved in the wind. The armature structure was badly corroded, and about two percent of the exterior plates needed to be replaced.[143] Although problems with the armature had been recognized as early as 1936, when cast iron replacements for some of the bars had been installed, much of the corrosion had been hidden by layers of paint applied over the years.[144]

In May 1982, President Ronald Reagan announced the formation of the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Centennial Commission, led by Chrysler Corporation chair Lee Iacocca, to raise the funds needed to complete the work.[145][146][147] Through its fundraising arm, the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation, Inc., the group raised more than $350 million in donations for the renovations of both the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island.[148] The Statue of Liberty was one of the earliest beneficiaries of a cause marketing campaign. A 1983 promotion advertised that for each purchase made with an American Express card, the company would contribute one cent to the renovation of the statue. The campaign generated contributions of $1.7 million to the restoration project.[149]

In 1984, the statue was closed to the public for the duration of the renovation. Workers erected the world's largest free-standing scaffold,[35] which obscured the statue from view. Liquid nitrogen was used to remove layers of paint that had been applied to the interior of the copper skin over decades, leaving two layers of coal tar, originally applied to plug leaks and prevent corrosion. Blasting with baking soda powder removed the tar without further damaging the copper.[150] The restorers' work was hampered by the asbestos-based substance that Bartholdi had used—ineffectively, as inspections showed—to prevent galvanic corrosion. Workers within the statue had to wear protective gear, dubbed "Moon suits", with self-contained breathing circuits.[151] Larger holes in the copper skin were repaired, and new copper was added where necessary.[152] The replacement skin was taken from a copper rooftop at Bell Labs, which had a patina that closely resembled the statue's; in exchange, the laboratory was provided some of the old copper skin for testing.[153] The torch, found to have been leaking water since the 1916 alterations, was replaced with an exact replica of Bartholdi's unaltered torch.[154] Consideration was given to replacing the arm and shoulder; the National Park Service insisted that they be repaired instead.[155] The original torch was removed and replaced in 1986 with the current one, whose flame is covered in 24-karat gold.[38] The torch reflects the Sun's rays in daytime and is lighted by floodlights at night.[38]

The entire puddled iron armature designed by Gustave Eiffel was replaced. Low-carbon corrosion-resistant stainless steel bars that now hold the staples next to the skin are made of Ferralium, an alloy that bends slightly and returns to its original shape as the statue moves.[156] To prevent the ray and arm making contact, the ray was realigned by several degrees.[157] The lighting was again replaced—night-time illumination subsequently came from metal-halide lamps that send beams of light to particular parts of the pedestal or statue, showing off various details.[158] Access to the pedestal, which had been through a nondescript entrance built in the 1960s, was renovated to create a wide opening framed by a set of monumental bronze doors with designs symbolic of the renovation.[159] A modern elevator was installed, allowing disability access to the observation area of the pedestal.[160] An emergency elevator was installed within the statue, reaching up to the level of the shoulder.[161]

July 3–6, 1986, was designated "Liberty Weekend", marking the centennial of the statue and its reopening. President Reagan presided over the rededication, with French President François Mitterrand in attendance. July 4 saw a reprise of Operation Sail,[162] and the statue was reopened to the public on July 5.[163] In Reagan's dedication speech, he stated, "We are the keepers of the flame of liberty; we hold it high for the world to see."[162]

Closures and reopenings (2001–present)

Immediately following the September 11 attacks, the statue and Liberty Island were closed to the public. The island reopened at the end of 2001, while the pedestal and statue remained off-limits. The pedestal reopened in August 2004,[163] but the National Park Service announced that visitors could not safely be given access to the statue due to the difficulty of evacuation in an emergency. The Park Service adhered to that position through the remainder of the Bush administration.[164] New York Congressman Anthony Weiner made the statue's reopening a personal crusade.[165] On May 17, 2009, President Barack Obama's Secretary of the Interior, Ken Salazar, announced that as a "special gift" to America, the statue would be reopened to the public as of July 4, but that only a limited number of people would be permitted to ascend to the crown each day.[164]

The statue, including the pedestal and base, closed on October 29, 2011, for installation of new elevators and staircases and to bring other facilities, such as restrooms, up to code. The statue was reopened on October 28, 2012,[166][167][168] but then closed again a day later in advance of Hurricane Sandy.[169] Although the storm did not harm the statue, it destroyed some of the infrastructure on both Liberty and Ellis Islands, including the dock used by the ferries that ran to Liberty and Ellis Islands. On November 8, 2012, a Park Service spokesperson announced that both islands would remain closed for an indefinite period for repairs to be done.[170] Since Liberty Island had no electricity, a generator was installed to power temporary floodlights to illuminate the statue at night. The superintendent of Statue of Liberty National Monument, David Luchsinger—whose home on the island was severely damaged—stated that it would be "optimistically ... months" before the island was reopened to the public.[171] The statue and Liberty Island reopened to the public on July 4, 2013.[172] Ellis Island remained closed for repairs for several more months but reopened in late October 2013.[173]

The Statue of Liberty has also been closed due to government shutdowns and protests, as well as for disease pandemics. During the October 2013 United States federal government shutdown, Liberty Island and other federally funded sites were closed.[174] In addition, Liberty Island was briefly closed on July 4, 2018, after a woman protesting against American immigration policy climbed onto the statue.[175] However, the island remained open during the 2018–19 United States federal government shutdown because the Statue of Liberty–Ellis Island Foundation had donated funds.[176] It closed beginning on March 16, 2020, due to the COVID-19 pandemic.[177] On July 20, 2020, the Statue of Liberty reopened partially under New York City's Phase IV guidelines, with Ellis Island remaining closed.[178][179] The crown did not reopen until October 2022.[180]

On October 7, 2016, construction started on the new Statue of Liberty Museum on Liberty Island.[181] The new $70 million, 26,000-square-foot (2,400 m2) museum may be visited by all who come to the island,[182] as opposed to the museum in the pedestal, which only 20% of the island's visitors had access to.[181] The new museum, designed by FXFOWLE Architects, is integrated with the surrounding parkland.[183][184] Diane von Fürstenberg headed the fundraising for the museum, and the project received over $40 million in fundraising by groundbreaking.[183] The museum opened on May 16, 2019.[185][186]

Access and attributes

Location and access

The statue is situated in Upper New York Bay on Liberty Island south of Ellis Island, which together comprise the Statue of Liberty National Monument. Both islands were ceded by New York to the federal government in 1800.[187] As agreed in an 1834 compact between New York and New Jersey that set the state border at the bay's midpoint, the original islands remain New York territory though located on the New Jersey side of the state line. Liberty Island is one of the islands that are part of the borough of Manhattan in New York. Land created by reclamation added to the 2.3-acre (0.93 ha) original island at Ellis Island is New Jersey territory.[188]

No charge is made for entrance to the national monument, but there is a cost for the ferry service that all visitors must use,[189] as private boats may not dock at the island. A concession was granted in 2007 to Statue Cruises to operate the transportation and ticketing facilities, replacing Circle Line, which had operated the service since 1953.[190] The ferries, which depart from Liberty State Park in Jersey City and the Battery in Lower Manhattan, also stop at Ellis Island when it is open to the public, making a combined trip possible.[191] All ferry riders are subject to security screening, similar to airport procedures, prior to boarding.[192]

Visitors intending to enter the statue's base and pedestal must obtain pedestal access for a nominal fee when purchasing their ferry ticket.[189][193] Those wishing to climb the staircase within the statue to the crown must purchase a special ticket, which may be reserved up to a year in advance. A total of 240 people per day can ascend: ten per group, three groups per hour. Climbers may bring only medication and cameras—lockers are provided for other items—and must undergo a second security screening.[194] The balcony around the torch was closed to the public following the munitions explosion on Black Tom Island in 1916.[116] The balcony can however be seen live via webcam.[195]

Inscriptions, plaques, and dedications

There are several plaques and dedicatory tablets on or near the Statue of Liberty.

- A plaque on the copper just under the figure in front declares that it is a colossal statue representing Liberty, designed by Bartholdi and built by the Paris firm of Gaget, Gauthier et Cie (Cie is the French abbreviation analogous to Co.).[196]

- A presentation tablet, also bearing Bartholdi's name, declares the statue is a gift from the people of the Republic of France that honors "the Alliance of the two Nations in achieving the Independence of the United States of America and attests their abiding friendship."[196]

- A tablet placed by the American Committee commemorates the fundraising done to build the pedestal.[196]

- The cornerstone bears a plaque placed by the Freemasons.[196]

- In 1903, a bronze tablet that bears the text of Emma Lazarus's sonnet, "The New Colossus" (1883), was presented by friends of the poet. Until the 1986 renovation, it was mounted inside the pedestal; later, it resided in the Statue of Liberty Museum, in the base.[196]

- "The New Colossus" tablet is accompanied by a tablet given by the Emma Lazarus Commemorative Committee in 1977, celebrating the poet's life.[196]

A group of statues stands at the western end of the island, honoring those closely associated with the Statue of Liberty. Two Americans—Pulitzer and Lazarus—and three Frenchmen—Bartholdi, Eiffel, and Laboulaye—are depicted. They are the work of Maryland sculptor Phillip Ratner.[197]

Historical designations

President Calvin Coolidge officially designated the Statue of Liberty as part of the Statue of Liberty National Monument in 1924.[2][198] The monument was expanded to also include Ellis Island in 1965.[199][200] The following year, the Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island were jointly added to the National Register of Historic Places,[201] and the statue individually in 2017.[4] On the sub-national level, the Statue of Liberty National Monument was added to the New Jersey Register of Historic Places in 1971,[5] and was made a New York City designated landmark in 1976.[7]

In 1984, the Statue of Liberty was designated a UNESCO World Heritage Site. The UNESCO "Statement of Significance" describes the statue as a "masterpiece of the human spirit" that "endures as a highly potent symbol—inspiring contemplation, debate and protest—of ideals such as liberty, peace, human rights, abolition of slavery, democracy and opportunity."[202]

Measurements

| Feature[79] | Imperial | Metric |

|---|---|---|

| Height of copper statue | 151 ft 1 in | 46 m |

| Foundation of pedestal (ground level) to tip of torch | 305 ft 1 in | 93 m |

| Heel to top of head | 111 ft 1 in | 34 m |

| Height of hand | 16 ft 5 in | 5 m |

| Index finger | 8 ft 1 in | 2.44 m |

| Circumference at second joint | 3 ft 6 in | 1.07 m |

| Head from chin to cranium | 17 ft 3 in | 5.26 m |

| Head thickness from ear to ear | 10 ft 0 in | 3.05 m |

| Distance across the eye | 2 ft 6 in | 0.76 m |

| Length of nose | 4 ft 6 in | 1.48 m |

| Right arm length | 42 ft 0 in | 12.8 m |

| Right arm greatest thickness | 12 ft 0 in | 3.66 m |

| Thickness of waist | 35 ft 0 in | 10.67 m |

| Width of mouth | 3 ft 0 in | 0.91 m |

| Tablet, length | 23 ft 7 in | 7.19 m |

| Tablet, width | 13 ft 7 in | 4.14 m |

| Tablet, thickness | 2 ft 0 in | 0.61 m |

| Height of pedestal | 89 ft 0 in | 27.13 m |

| Height of foundation | 65 ft 0 in | 19.81 m |

| Weight of copper used in statue | 60,000 pounds | 27.22 tonnes |

| Weight of steel used in statue | 250,000 pounds | 113.4 tonnes |

| Total weight of statue | 450,000 pounds | 204.1 tonnes |

| Thickness of copper sheeting | 3/32 of an inch | 2.4 mm |

Depictions

Hundreds of replicas of the Statue of Liberty are displayed worldwide.[203] A smaller version of the statue, one-fourth the height of the original, was given by the American community in Paris to that city. It now stands on the Île aux Cygnes, facing west toward her larger sister.[203] A replica 30 feet (9.1 m) tall stood atop the Liberty Warehouse on West 64th Street in Manhattan for many years;[203] it now resides at the Brooklyn Museum.[204] In a patriotic tribute, the Boy Scouts of America, as part of their Strengthen the Arm of Liberty campaign in 1949–1952, donated about two hundred replicas of the statue, made of stamped copper and 100 inches (2.5 m) in height, to states and municipalities across the United States.[205] Though not a true replica, the statue known as the Goddess of Democracy temporarily erected during the Tiananmen Square protests of 1989 was similarly inspired by French democratic traditions—the sculptors took care to avoid a direct imitation of the Statue of Liberty.[206] Among other recreations of New York City structures, a replica of the statue is part of the exterior of the New York-New York Hotel and Casino in Las Vegas.[207]

As an American icon, the Statue of Liberty has been depicted on the country's coinage and stamps. It appeared on commemorative coins issued to mark its 1986 centennial, and on New York's 2001 entry in the state quarters series.[208] An image of the statue was chosen for the American Eagle platinum bullion coins in 1997, and it was placed on the reverse, or tails, side of the Presidential Dollar series of circulating coins.[33] Two images of the statue's torch appear on the current ten-dollar bill.[209] The statue's intended photographic depiction on a 2010 forever stamp proved instead to be of the replica at the Las Vegas casino.[210]

Depictions of the statue have been used by many regional institutions. Between 1986[211] and 2000,[212] New York State issued license plates with an outline of the statue.[211][212] The Women's National Basketball Association's New York Liberty use both the statue's name and its image in their logo, in which the torch's flame doubles as a basketball.[213] The New York Rangers of the National Hockey League depicted the statue's head on their third jersey, beginning in 1997.[214] The National Collegiate Athletic Association's 1996 Men's Basketball Final Four, played at New Jersey's Meadowlands Sports Complex, featured the statue in its logo.[215] The Libertarian Party of the United States uses the statue in its emblem.[216]

The statue is a frequent subject in popular culture. In music, it has been evoked to indicate support for American policies, as in Toby Keith's 2002 song "Courtesy of the Red, White and Blue (The Angry American)", and in opposition, appearing on the cover of the Dead Kennedys' album Bedtime for Democracy, which protested the Reagan administration.[217] In film, the torch is the setting for the climax of director Alfred Hitchcock's 1942 movie Saboteur.[218] The statue makes one of its most famous cinematic appearances in the 1968 picture Planet of the Apes, in which it is seen half-buried in sand.[217][219] It is knocked over in the science-fiction film Independence Day and in Cloverfield the head is ripped off.[220] In Jack Finney's 1970 time-travel novel Time and Again, the right arm of the statue, on display in the early 1880s in Madison Square Park, plays a crucial role.[221] Robert Holdstock, consulting editor of The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction, wondered in 1979:

Where would science fiction be without the Statue of Liberty? For decades it has towered or crumbled above the wastelands of deserted Earth—giants have uprooted it, aliens have found it curious ... the symbol of Liberty, of optimism, has become a symbol of science fiction's pessimistic view of the future.[222]

-

Head of Liberty, U.S. airmail stamp, 1971

-

Reverse side of a Presidential Dollar coin

-

3D model. Click to interact.

See also

- Goddess of Liberty, 1888 statue by Elijah E. Myers atop the Texas State Capitol dome in Austin, Texas

- Miss Freedom, 1889 statue on the dome of the Georgia State Capitol (US)

- Place des États-Unis, in Paris, France

- The Statue of Liberty (film), a 1985 Ken Burns documentary film

- Statues and sculptures in New York City

- List of tallest statues

References

Citations

- ^ Schneiderman, R.M. (June 28, 2010). "For tourists, Statue of Liberty is nice, but no Forever 21". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on January 24, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ a b "National Monument Proclamations under the Antiquities Act". National Park Service. January 16, 2003. Archived from the original on October 25, 2011. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "Liberty Enlightening the World". Washington, D.C.: National Park Service. Archived from the original on January 1, 2020. Retrieved February 12, 2020.

- ^ a b Weekly List of Actions Taken on Properties: 9/08/2017 through 9/14/2017, National Park Service, September 14, 2017, archived from the original on December 29, 2018, retrieved July 13, 2019.

- ^ a b "New Jersey and National Registers of Historic Places – Hudson County". New Jersey Department of Environmental Protection – Historic Preservation Office. Archived from the original on October 9, 2014. Retrieved August 2, 2014.

- ^ "Cultural Resource Information System (CRIS)". New York State Office of Parks, Recreation and Historic Preservation. November 7, 2014. Retrieved July 20, 2023.

- ^ a b "Statue of Liberty National Monument" (PDF). New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission. September 14, 1976. Archived (PDF) from the original on December 26, 2016. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "Abolition". Statue of Liberty National Monument. National Park Service. February 26, 2015. Archived from the original on November 8, 2019. Retrieved November 18, 2019.

- ^ "The French Connection". National Park Service. May 19, 2019. Retrieved June 10, 2023.

- ^ a b c Harris 1985, pp. 7–9.

- ^ Joseph, Rebecca M.; Rosenblatt, Brooke; Kinebrew, Carolyn (September 2000). "The Black Statue of Liberty Rumor". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved July 31, 2012.

- ^ "Abolition". National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 14, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "The Statue of Liberty and its Ties to the Middle East" (PDF). University of Chicago. Archived (PDF) from the original on April 20, 2015. Retrieved February 8, 2017.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 7–8.

- ^ Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 243. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 60–61.

- ^ a b Moreno 2000, pp. 39–40.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 12–13.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 102–103.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 16–17.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, p. 85.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 10–11.

- ^ a b c d e Sutherland 2003, pp. 17–19.

- ^ a b c d e Bodnar, John (2006). "Monuments and Morals: The Nationalization of Civic Instruction". In Warren, Donald R.; Patrick, John J. (eds.). Civic and Moral Learning in America. Macmillan. pp. 212–214. ISBN 978-1-4039-7396-2. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ The encyclopedia of ancient history. Bagnall, Roger S. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell. 2013. ISBN 978-1-4051-7935-5. OCLC 230191195.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: others (link) - ^ Roberts, J. M. (John Morris), 1928-2003. (1993). History of the world. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-19-521043-3. OCLC 28378422.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Turner, Jane (2000). The Grove Dictionary of Art: From Monet to Cézanne : Late 19th-century French Artists. Oxford University Press US. p. 10. ISBN 978-0-312-22971-9. Archived from the original on February 4, 2021. Retrieved October 3, 2020.

- ^ Harrison, Marissa A. (2010). "An exploratory study of the relationship between second toe length and androgen-linked behaviors". Journal of Social, Evolutionary, and Cultural Psychology. 4 (4): 241–253. doi:10.1037/h0099286.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 96–97.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, pp. 105–108.

- ^ Blume, Mary (July 16, 2004). "The French icon Marianne à la mode". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ "Get the Facts (Frequently Asked Questions about the Statue of Liberty)". Statue of Liberty. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 6, 2017. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ a b "Lady Liberty Reverse Statue of Liberty (1886)". Presidential $1 coin. United States Mint. Archived from the original on December 11, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ Moreno 2000, pp. 52–53, 55, 87.

- ^ a b c d e f g Interviewed for Watson, Corin. Statue of Liberty: Building a Colossus (TV documentary, 2001)

- ^ Bartholdi, Frédéric (1885). The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World. North American Review. p. 42.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, pp. 108–111.

- ^ a b c "Frequently asked questions". Statue of Liberty National Monument. National Park Service. Archived from the original on August 7, 2017. Retrieved August 10, 2010.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 120.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 118, 125.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 26.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 121.

- ^ a b c Khan 2010, pp. 123–125.

- ^ a b Harris 1985, pp. 44–45.

- ^ "News of Norway". 1999. Archived from the original on September 16, 2011. Retrieved July 29, 2010.

- ^ "Answers about the Statue of Liberty, Part 2". The New York Times. July 2, 2009. Archived from the original on March 15, 2012. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Sutherland 2003, p. 36.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 126–128.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 25.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 26.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 130.

- ^ a b Harris 1985, p. 49.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, p. 134.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 30.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 94.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 135.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, p. 137.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 32.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 136–137.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 22.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 139–143.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 30.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 33.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 32.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 34.

- ^ "La tour a vu le jour à Levallois". Le Parisien (in French). April 30, 2004. Archived from the original on April 7, 2019. Retrieved December 8, 2012.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 144.

- ^ "Statue of Liberty". PBS. Archived from the original on October 27, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 36–38.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 39.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 38.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 37.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 38.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, pp. 159–160.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 163.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 161.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, p. 160.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 91.

- ^ a b "Statistics". Statue of Liberty. National Park Service. August 16, 2006. Archived from the original on July 1, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, p. 169.

- ^ a b c Auchincloss, Louis (May 12, 1986). "Liberty: Building on the Past". New York. p. 87. Archived from the original on February 3, 2021. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Bartholdi, Frédéric (1885). The Statue of Liberty Enlightening the World. North American Review. p. 62.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 71–72.

- ^ Sutherland 2003, pp. 49–50.

- ^ a b Moreno 2000, pp. 184–186.

- ^ "Branford's History Is Set in Stone". Connecticut Humanities. Archived from the original on November 29, 2013. Retrieved July 3, 2013.

- ^ "STRUCTUREmag – Structural Engineering Magazine, Tradeshow: Joachim Gotsche Giaver". November 27, 2012. Archived from the original on November 27, 2012.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 163–164.

- ^ Khan 2010, pp. 165–166.

- ^ Moreno 2000, pp. 172–175.

- ^ "A World Room Welcome". blogs.cul.columbia.edu. January 23, 2023. Retrieved January 25, 2023.

- ^ Levine, Benjamin; Story, Isabelle F. (1961). "Statue of Liberty". National Park Service. Archived from the original on February 1, 2014. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, pp. 40–41.

- ^ a b c Harris 1985, p. 105.

- ^ Sutherland 2003, p. 51.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 107.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 110–111.

- ^ Mitchell, Elizabeth (2014). Liberty's Torch: The Great Adventure to Build the Statue of Liberty. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 221. ISBN 978-0-8021-2257-5.

- ^ Andrews, Elisha Benjamin (1896). The History of the Last Quarter-century in the United States, 1870-1895. Scribner. p. 133.

- ^ The World Almanac & Book of Facts. Newspaper Enterprise Association. 1927. p. 543.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 112.

- ^ "The Isere-Bartholdi Gift Reaches the Horseshoe Safely" (PDF). The Evening Post. June 17, 1885. Archived (PDF) from the original on January 12, 2021. Retrieved February 11, 2013.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 114.

- ^ a b Moreno 2000, p. 19.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 49.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 64.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 36.

- ^ a b c Harris 1985, pp. 133–134.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 65.

- ^ Mitchell, Elizabeth (2014). Liberty's Torch: The Great Adventure to Build the Statue of Liberty. Atlantic Monthly Press. p. 259. ISBN 978-0-8021-9255-4.

- ^ "Statue Color". NBC News. Archived from the original on January 17, 2024. Retrieved January 19, 2024.

- ^ Khan 2010, p. 176.

- ^ a b Khan 2010, pp. 177–178.

- ^ Bell & Abrams 1984, p. 52.

- ^ a b Harris 1985, p. 127.

- ^ a b c Moreno 2000, p. 71.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 128.

- ^ "Postponing Bartholdi's statue until there is liberty for colored as well". The Cleveland Gazette. Cleveland, Ohio. November 27, 1886. p. 2.

- ^ a b c d Moreno 2000, p. 41.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 24.

- ^ "The immigrants' statue". National Park Service. February 26, 2015. Archived from the original on February 28, 2020. Retrieved April 8, 2020.

- ^ a b Sutherland 2003, p. 78.

- ^ "Answers about the Statue of Liberty". The New York Times. July 1, 2009. Archived from the original on September 22, 2011. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ "To paint Miss Liberty". The New York Times. July 19, 1906. p. 1. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ "How shall "Miss Liberty"'s toilet be made?". The New York Times. July 29, 1906. pp. SM2. Archived from the original on September 28, 2018. Retrieved October 19, 2011.

- ^ a b Harris 1985, p. 168.

- ^ Rielage, Dale C. (January 1, 2002). Russian Supply Efforts in America During the First World War. McFarland. p. 71. ISBN 978-0-7864-1337-9. Archived from the original on January 4, 2024. Retrieved January 21, 2024.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 136–139.

- ^ Moreno 2000, pp. 148–151.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 147.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 136.

- ^ a b Moreno 2000, p. 202.

- ^ a b Harris 1985, p. 169.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 141–143.

- ^ Moreno 2000, pp. 147–148.

- ^ "Honorees". Lapride.org. January 4, 2007. Archived from the original on September 6, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ "The Feminist Chronicles, 1953–1993 – 1970 – Feminist Majority Foundation". Feminist.org. Archived from the original on October 12, 2012. Retrieved November 6, 2012.

- ^ 1973 World Almanac and Book of Facts, p. 996.

- ^ Moreno 2000, pp. 72–73.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 143.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 20.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 165.

- ^ Harris 1985, pp. 169–171.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 38.

- ^ "Repairs due for Miss Liberty". Asbury Park Press. Associated Press. June 20, 1982. p. 3. Archived from the original on October 10, 2021. Retrieved June 5, 2019 – via newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Krebs, Albin; Thomas, Robert McG. Jr. (May 19, 1982). "NOTES ON PEOPLE; Iacocca to Head Drive to Restore Landmarks". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 8, 2019. Retrieved June 8, 2019.

- ^ Moreno 2000, pp. 204–205.

- ^ Moreno 2000, pp. 216–218.

- ^ Daw, Jocelyne (March 2006). Cause Marketing for Nonprofits: Partner for Purpose, Passion, and Profits. Hoboken, New Jersey: John Wiley & Sons. p. 4. ISBN 978-0-471-71750-8.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 81.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 76.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 55.

- ^ Harris 1985, p. 172.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 153.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 75.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, pp. 74–76.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 57.

- ^ Moreno 2000, p. 153.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 71.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 84.

- ^ Hayden & Despont 1986, p. 88.

- ^ a b Sutherland 2003, p. 106.

- ^ a b "History and Culture". Statue of Liberty. National Park Service. Archived from the original on July 13, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ a b Chan, Sewell (May 8, 2009). "Statue of Liberty's Crown Will Reopen July 4". The New York Times. Archived from the original on January 6, 2014. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ Neuman, William (July 5, 2007). "Congress to Ask Why Miss Liberty's Crown is Still Closed to Visitors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on May 17, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Statue of Liberty National Monument". National Park Service. December 31, 2007. Archived from the original on July 31, 2014. Retrieved October 12, 2011.

- ^ Raja, Nina (August 10, 2010). "Liberty Island to remain open during statue's renovation". CNN. Archived from the original on July 3, 2013. Retrieved October 20, 2011.

- ^ "Statue of Liberty interior to re-open next month". AP via Fox News. September 11, 2012. Archived from the original on June 3, 2016. Retrieved May 6, 2016.

- ^ Powlowski, A. (November 2, 2012). "Statue of Liberty closed for 'foreseeable future'". NBC News. Archived from the original on November 2, 2012. Retrieved November 2, 2012.

- ^ McGeehan, Patrick (November 8, 2012). "Storm leaves Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island cut off from visitors". The New York Times. Archived from the original on November 10, 2012. Retrieved November 9, 2012.

- ^ Barron, James (November 30, 2012). "Statue of Liberty was unscathed by hurricane, but its home took a beating". The New York Times. Archived from the original on December 1, 2012. Retrieved December 1, 2012.

- ^ Long, Colleen (July 4, 2013). "Statue of Liberty reopens as US marks July Fourth". Yahoo! News. Archived from the original on July 7, 2013. Retrieved July 4, 2013.

- ^ Foderaro, Lisa (October 28, 2013). "Ellis Island Welcoming Visitors Once Again, but Repairs Continue". The New York Times. Archived from the original on July 8, 2015. Retrieved October 19, 2014.

- ^ Armaghan, Sarah (October 1, 2013). "Statue of Liberty Closed in Shutdown". The Wall Street Journal. Archived from the original on August 18, 2017. Retrieved August 4, 2017.

- ^ Shannon, James. "Woman Climbs Base of the Statue of Liberty After ICE Protest". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on July 4, 2018. Retrieved July 5, 2018.

- ^ "Additional funds will keep Statue of Liberty, Ellis Island open during federal shutdown". NorthJersey.com. January 15, 2019. Archived from the original on March 1, 2019. Retrieved February 28, 2019.

- ^ Kim, Allen (March 16, 2020). "Statue of Liberty and Ellis Island close due to coronavirus outbreak". CNN. Archived from the original on March 17, 2020. Retrieved March 17, 2020.

- ^ "Statue of Liberty to Open Early Next Week, Ellis Island Kept Closed". NBC New York. July 13, 2020. Archived from the original on August 8, 2020. Retrieved August 3, 2020.