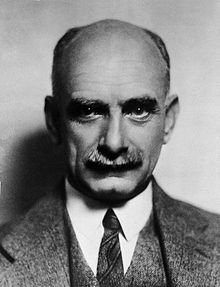

Thomas Lewis (cardiologist)

Sir Thomas Lewis, CBE, FRS, FRCP[1] (26 December 1881 – 17 March 1945) was a Welsh cardiologist.[A][2][3][4][5][6][7][8] He coined the term "clinical science" and is also known for the Lewis P Factor.[2][9]

Early life and education[edit]

Lewis was born in Taffs Well,[10][11][12] Cardiff, Wales, the son of Henry Lewis, a mining engineer, and his wife Catherine Hannah (née Davies). He was educated at home by his mother, apart from a year at Clifton College,[13] which he left due to ill-health, and the final two years by a tutor. Already planning to become a doctor, at the age of sixteen he began a Bachelor of Science (BSc) course at University College, Cardiff, graduating three years later with first class honours. In 1902 he entered University College Hospital (UCH) in London to train as a doctor, graduating MBBS with the gold medal in 1905. The same year he was awarded a Doctor of Science (DSc) degree from the University of Wales for his research work.

Career[edit]

Lewis remained at UCH for the rest of his life, beginning as a house physician. From 1907 he also worked at the Royal Naval Hospital, Greenwich and the City of London Hospital and the same year he took his Doctor of Medicine (MD) degree. In 1911 he was appointed lecturer in cardiac pathology at UCH and in 1913 was promoted to assistant physician in clinical work. He was elected Fellow of the Royal College of Physicians (FRCP) in 1913.

While still a house physician, Lewis began physiological research, carrying out fundamental research on the heart, the pulse and blood pressure. From 1906, he corresponded with the Dutch physiologist Willem Einthoven concerning the latter's invention of the string galvanometer and electrocardiography, and Lewis pioneered its use in clinical settings. Accordingly, Lewis is considered the "father of clinical cardiac electrophysiology". The first use of electrocardiography in clinical medicine was in 1908. In that year, Thomas Lewis and Arthur MacNalty (later the Chief Medical Officer of the United Kingdom) employed electrocardiography to diagnose heart block.[14] In 1909, with James MacKenzie, Lewis founded the journal Heart: A Journal for the Study of the Circulation, which he renamed Clinical Science in 1933. In 1913, he published the book Clinical Electrocardiography, the first treaty on electrocardiography. Lewis was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society (FRS) in 1918.[1] He was promoted to full physician at UCH in 1919.

During the First World War, Lewis worked at the Military Heart Hospital in Hampstead and was appointed to the first full-time clinical research post in Britain, at the Medical Research Committee (later Medical Research Council). He directed a study of the condition known as "soldier's heart" and, having established it was not a cardiological problem, renamed it the "effort syndrome".[2] In 1918 he wrote the monograph The Soldier's Heart and the Effort Syndrome. He devised remedial exercises that allowed many soldiers suffering from the condition to return to duty and was appointed honorary consulting physician to the Ministry of Pensions in April 1919, and for this work he was appointed Commander of the Order of the British Empire (CBE) in January 1920[15] and was knighted in the 1921 Birthday Honours.[16]

After the war, Lewis established the clinical research department at UCH and continued his work on cardiac arrhythmia. In 1925 he switched his focus from cardiography to vascular reactions of the skin. In 1917 he had shown that capillaries had independent contractions and he now investigated the response of the skin to injury, leading to the 1927 monograph The Blood Vessels of the Human Skin and their Responses. He was awarded the Royal Society's Royal Medal in 1927 "for his researches on the vascular system, following upon his earlier work on the mammalian heart-beat." Next, he switched his focus to peripheral vascular disease, especially Raynaud's disease, and finally to the mechanism of pain, summarising his findings in Pain in 1942. His 1932 book Diseases of the Heart became a standard medical text. In 1930 he described the Hunting reaction, alternating vasodilation and vasoconstriction of peripheral capillaries in cold environments.

In 1930, he founded the Medical Research Society. He was awarded the Royal Society's Copley Medal in 1941 "for his clinical and experimental investigations upon the mammalian heart." He was only the second clinician to receive it, after Lord Lister in 1902. He served as vice-president of the Royal Society from 1943 to 1945.

Lewis suffered a myocardial infarction at the age of 45 and gave up his 70-cigarette-a-day habit, being one of the first to realise that smoking damaged the blood vessels.[2] He died from coronary heart disease at his home at Loudwater, Hertfordshire, on 17 March 1945, at age 63.

Family[edit]

Lewis married Alice Lorna Treharne James in 1916. They had three children.

Publications[edit]

- The Mechanism of the Heart Beat (1911)

- Clinical Electro-Cardiography (1913)

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ Lewis personally disliked the term "cardiologist" and preferred to describe himself as a cardiovascular disease specialist.[2]

Citations[edit]

- ^ a b Drury, A. N.; Grant, R. T. (1945). "Thomas Lewis. 1881-1945". Obituary Notices of Fellows of the Royal Society. 5 (14): 179. doi:10.1098/rsbm.1945.0012. S2CID 72220548.

- ^ a b c d e Biography, Oxford Dictionary of National Biography

- ^ Cygankiewicz, I. (2007). "Sir Thomas Lewis (1881-1945)". Cardiology Journal. 14 (6): 605–606. PMID 18651531.

- ^ Pearce, J. M. S. (2006). "Sir Thomas Lewis MD, FRS. (1881–1945)". Journal of Neurology. 253 (9): 1246–1247. doi:10.1007/s00415-006-0166-3. PMID 16990996. S2CID 33093678.

- ^ Haas, L. F. (2005). "Sir Thomas Lewis 1881-1945". Journal of Neurology, Neurosurgery & Psychiatry. 76 (8): 1157. doi:10.1136/jnnp.2004.055269. PMC 1739765. PMID 16024897.

- ^ Krikler, D. M. (1997). "Thomas Lewis, a father of modern cardiology". Heart. 77 (2): 102–103. doi:10.1136/hrt.77.2.102. PMC 484655. PMID 9068389.

- ^ Hollman, Arthur (1997). Sir Thomas Lewis: Pioneer Cardiologist and Clinical Scientist. Santa Clara, CA: Springer-Verlag TELOS. ISBN 978-3-540-76049-8.

- ^ Hollman, A. (1994). "Sir Thomas Lewis: Clinical scientist and cardiologist, 1881-1945". Journal of Medical Biography. 2 (2): 63–70. doi:10.1177/096777209400200201. PMID 11639239. S2CID 22520472.

- ^ Birdsong, William T. (18 November 2010). "Sensing Muscle Ischemia: Coincident Detection of Acid and ATP via Interplay of Two Ion Channels". Neuron. 68 (4): 739–749 – via Cell Press.

- ^ "Obituary". British Medical Journal. 461 (British Medical Journal): 1. 31 March 1945. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ "The National Library of Wales :: Dictionary of Welsh Biography". The National Library of Wales. Retrieved 17 June 2015.

- ^ Hollman, Arthur (1997). Sir Thomas Lewis : pioneer cardiologist and clinical scientist. London: Springer. ISBN 978-3540760498.

- ^ "Clifton College Register" Muirhead, J.A.O. p180: Bristol; J.W Arrowsmith for Old Cliftonian Society; April, 1948

- ^ ”A note on the simultaneous occurrence of sinus and ventricular rhythm in man”, Lewis T, Macnalty AS, J. Physiol. 1908 Dec 15;37(5–6):445-58

- ^ "No. 31760". The London Gazette (Supplement). 27 January 1920. p. 1237.

- ^ "No. 32346". The London Gazette (Supplement). 4 June 1921. p. 4531.

- 1881 births

- 1945 deaths

- People from Taff's Well

- Medical doctors from Cardiff

- People educated at Clifton College

- Alumni of Cardiff University

- Alumni of the UCL Medical School

- 20th-century Welsh medical doctors

- British cardiologists

- British physiologists

- Commanders of the Order of the British Empire

- Knights Bachelor

- Fellows of the Royal Society

- Fellows of the Royal College of Physicians

- Recipients of the Copley Medal

- Royal Medal winners