Translating The Lord of the Rings

J. R. R. Tolkien's The Lord of the Rings has been translated, with varying degrees of success, into dozens of languages from the original English. Tolkien, an expert in Germanic philology, scrutinized those that were under preparation during his lifetime, and made comments on early translations that reflect both the translation process and his work. To aid translators, and because he was unhappy with the work of early translators such as Åke Ohlmarks with his Swedish version,[1] Tolkien wrote his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings in 1967 (released publicly in 1975 in A Tolkien Compass, and in full in 2005, in The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion).

Challenges to translation[edit]

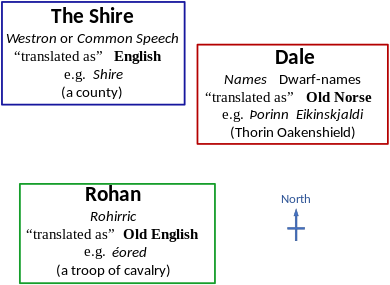

Because The Lord of the Rings purports to be a translation of the Red Book of Westmarch, with the English language in the translation purporting to represent the Westron of the original, translators need to imitate the complex interplay between English and non-English (Elvish) nomenclature in the book. An additional difficulty is the presence of proper names in Old English and Old Norse. Tolkien chose to use Old English for names and some words of the Rohirrim, for example, "Théoden", King of Rohan: his name is simply a transliteration of Old English þēoden, "king". Similarly, he used Old Norse for "external" names of his Dwarves, such as "Thorin Oakenshield": both Þorinn and Eikinskjaldi are Dwarf-names from the Völuspá.[2]

The relation of such names to English, within the history of English, and of the Germanic languages more generally, is intended to reflect the relation of the purported "original" names to Westron. The Tolkien scholar Tom Shippey states that Tolkien began with the words and names that he wanted, and invented parts of Middle-earth to resolve the linguistic puzzle he had accidentally created by using different European languages for those of peoples in his legendarium.[2]

Early translations[edit]

The first translations of The Lord of the Rings to be prepared were those in Dutch (1956–7, Max Schuchart) and Swedish (1959–60, Åke Ohlmarks). Both took considerable liberties with their material, apparent already from the rendition of the title, In de Ban van de Ring "Under the Spell of the Ring" and Härskarringen "The Ruling Ring", respectively.[3]

Most later translations, beginning with the Polish Władca Pierścieni in 1961, render the title more literally. Later non-literal title translations however include the Japanese 指輪物語 (Hepburn: Yubiwa Monogatari) "Tale of the Ring", Finnish Taru Sormusten Herrasta "Legend of the Lord of the Rings", the first Norwegian translation Krigen om ringen "The War of the Ring", Icelandic Hringadróttinssaga "The Lord of the Rings' Saga", and West Frisian, Master fan Alle Ringen "Master of All Rings".

Tolkien in both the Dutch and the Swedish cases objected strongly while the translations were in progress, in particular regarding the adaptation of proper names. Despite lengthy correspondence, Tolkien did not succeed in convincing the Dutch translator of his objections, and was similarly frustrated in the Swedish case.

Dutch (Schuchart) 1956–1957[edit]

On Max Schuchart's Dutch version, In de Ban van de Ring, Tolkien wrote

In principle I object as strongly as is possible to the 'translation' of the nomenclature at all (even by a competent person). I wonder why a translator should think himself called on or entitled to do any such thing. That this is an 'imaginary' world does not give him any right to remodel it according to his fancy, even if he could in a few months create a new coherent structure which it took me years to work out. [...] May I say at once that I will not tolerate any similar tinkering with the personal nomenclature. Nor with the name/word Hobbit.

— 3 July 1956, to Rayner Unwin, Letters, #190, pp. 249–51

Despite this, the Dutch version stayed largely unchanged except for the names of certain characters. Schuchart's translation remains, as of 2008, the only authorized translation in Dutch. An unauthorized translation was made by E.J. Mensink-van Warmelo in the late 1970s.[4][5] A revision of Schuchart's translation was initiated in 2003, but the publisher Uitgeverij M decided against publishing it.

Swedish[edit]

Ohlmarks 1959–1961[edit]

Åke Ohlmarks was a prolific translator, who during his career published Swedish versions of Shakespeare, Dante and the Qur'an as well as Tolkien. Tolkien intensely disliked Ohlmarks' translation of The Lord of the Rings (which Ohlmarks named Härskarringen, 'The Ruling Ring'), however, more so even than Schuchart's Dutch translation. Ohlmarks' translation remained the only one available in Swedish for forty years, and until his death in 1984, Ohlmarks remained impervious to the numerous complaints and calls for revision from readers.[3]

After The Silmarillion was published in 1977, Christopher Tolkien consented to a Swedish translation only on the condition that Ohlmarks have nothing to do with it. After a fire at his home in 1982, Ohlmarks incoherently charged Tolkien fans with arson, and subsequently published the book Tolkien och den svarta magin (Tolkien and the black magic) - a book connecting Tolkien with "black magic" and Nazism.[6]

Andersson and Olsson 2005[edit]

Ohlmarks' translation was superseded only in 2005, by a new translation by Erik Andersson with poems interpreted by Lotta Olsson. The work was retitled Ringarnas herre, 'The Rings' Lord'.[7]

| Tolkien | Ohlmarks 1959–1961 | Andersson and Olsson 2005 |

|---|---|---|

| Indeed, few Hobbits had ever seen or sailed upon the Sea, and fewer still had ever returned to report it. | Det var ju så, att sjömanslivet alls inte passade samman med hobernas allmänna läggning. Ytterst få hade sett havet, ännu färre befarit det, och av dem som verkligen seglat hade blott ett försvinnande fåtal återvänt och kunnat berätta om vad de upplevat. | Över huvud taget var det få hobbitar som hade sett havet eller färdats på det, och ännu färre hade återvänt och berättat om det. |

| (Translation of samples:) | It was the case that a sailor's life did not fit in at all with the general disposition of the hobbits. Extremely few had seen the sea, even fewer had sailed it, and of those who really had sailed, only a vanishingly few had returned and been able to tell what they had experienced. | Indeed there were few hobbits who had seen the sea or travelled on it, and even fewer had returned and told about it. |

German[edit]

Carroux 1969–1970[edit]

As a reaction to his disappointment with the Dutch and Swedish translations, Tolkien wrote his Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings, gaining himself a larger influence on translations into other Germanic languages, namely Danish and German. Frankfurt-based Margaret Carroux qualified for the German version published by Klett-Cotta on basis of her translation of Tolkien's short story "Leaf by Niggle", that she had translated solely to give him a sample of her work. In her preparation for The Lord of the Rings (Der Herr der Ringe), unlike Schluchart and Ohlmarks, Carroux even visited Tolkien in Oxford with a suitcase full of his published works and questions about them. Yet, mainly due to a cold that both Tolkien and his wife were going through at the time, the meeting was later described as inhospitable and 'chilly', Tolkien being 'harsh', 'taciturn' and 'severely ill'.[8] Later correspondences with Carroux turned out to be much more encouraging with Tolkien being generally very pleased with Carroux's work, with the sole exception of the poems and songs, that would eventually be translated by poet Ebba-Margareta von Freymann.

On several instances Carroux departed from the literal, e.g. for the Shire. Tolkien endorsed the Gouw of the Dutch version and remarked that German Gau "seems to me suitable in Ger., unless its recent use in regional reorganization under Hitler has spoilt this very old word." Carroux decided that this was indeed the case, and opted for the more artificial Auenland "meadow-land" instead.

"Elf" was rendered with linguistic care as Elb, the plural Elves as Elben. The choice reflects Tolkien's suggestion:

With regard to German: I would suggest with diffidence that Elf, elfen, are perhaps to be avoided as equivalents of Elf, elven. Elf is, I believe, borrowed from English, and may retain some of the associations of a kind that I should particularly desire not to be present (if possible): e.g. those of Drayton or of A Midsummer Night's Dream [...] I wonder whether the word Alp (or better still the form Alb, still given in modern dictionaries as a variant, which is historically the more normal form) could not be used. It is the true cognate of English elf [...] The Elves of the 'mythology' of The L.R. are not actually equatable with the folklore traditions about 'fairies', and as I have said (Appendix F[...]) I should prefer the oldest available form of the name to be used, and leave it to acquire its own associations for readers of my tale.

The Elb chosen by Carroux instead of the suggested Alb is a construction by Jacob Grimm in his 1835 Teutonic Mythology. Grimm, like Tolkien, notes that German Elf is a loan from the English, and argues for the revival of the original German cognate, which survived in the adjective elbisch and in composed names like Elbegast. Grimm also notes that the correct plural of Elb would be Elbe, but Carroux does not follow in this and uses the plural Elben, denounced by Grimm as incorrect in his German Dictionary (s.v. Alb).

On many instances, though, the German version resorts to literal translations. Rivendell Tolkien considered as a particularly difficult case, and recommended to "translate by sense, or retain as seems best.", but Carroux opted for the literal Bruchtal. The name "Baggins" was rendered as Beutlin (containing the word Beutel meaning "bag").

Another case where Carroux translated the meaning rather than the actual words was the name of Shelob, formed from the pronoun she plus lob, a dialectal word for "spider" (according to Tolkien; the OED is only aware of its occurrence in Middle English). Tolkien gives no prescription; he merely notes that "The Dutch version retains Shelob, but the Swed. has the rather feeble Honmonstret ["she-monster"]." Carroux chose Kankra, an artificial feminine formation from dialectal German Kanker ('Daddy-longlegs', cognate to cancer).

Krege 2000[edit]

In 2000, Klett-Cotta published a new translation of The Lord of the Rings by Wolfgang Krege, not as a replacement of the old one, which throughout the years had gained a loyal following, but rather as an accompaniment. The new version focuses more on the differences in linguistic style that Tolkien employed to set apart the more biblical prose and the high style of elvish and human 'nobility' from the more colloquial 1940s English spoken by the Hobbits, something that he thought Carroux's more unified version was lacking. Krege's translation met mixed reception, the general argument of critics being that he took too many liberties in modernising the language of the Hobbits with the linguistic style of late 90s German that not only subverted the epic style of the narrative as a whole but also went beyond the stylistic differences intended by Tolkien. Klett-Cotta has continued to offer and continuously republishes both translations. Yet, for the 2012 republication of Krege's version, his most controversial decisions were partly reverted.

Russian[edit]

Interest in Russia awoke soon after the publication of The Lord of the Rings in 1955, long before the first Russian translation. A first effort at publication was made in the 1960s, but in order to comply with literary censorship in Soviet Russia, the work was considerably abridged and transformed. The ideological danger of the book was seen in the "hidden allegory 'of the conflict between the individualist West and the totalitarian, Communist East'", while, ironically, Marxist readings in the West conversely identified Tolkien's anti-industrial ideas as presented in the Shire with primitive communism, in a struggle with the evil forces of technocratic capitalism.[9][10]

Russian translations of The Lord of the Rings circulated as samizdat and were published only after the collapse of the Soviet Union, but then in great numbers; no less than ten official Russian translations appeared between 1990 and 2005.[9] Tolkien fandom grew especially rapidly during the early 1990s at Moscow State University. Many unofficial and incomplete translations are in circulation. The first translation appearing in print was that by Kistyakovski and Muravyov (volume 1, published 1982).

Hebrew[edit]

The first translation of The Lord of the Rings into Hebrew (שר הטבעות, Sar ha-Tabbaot) was done by Canaanite movement member Ruth Livnit, aided by Uriel Ofek as the translator of the verse. The 1977 version was considered a unique book for the sort of Hebrew that it used, until it was revised by Dr. Emanuel Lottem according to the second English edition, although still under the name of the previous translators, with Lottem as merely "The editor".[12]

The difference between the two versions is clear in the translation of names. "Elves", for an example, was first translated as "בני לילית" (Bneyi Lilith, i.e. the "Children of Lilith") but in the new edition was transcribed in the form of "Elefs" maintained through Yiddish as "עלף". The change was made because "Bneyi Lilith" essentially relates to the Babylonian-derived Jewish folklore character of Lilith, mother of all demons, an inappropriate name for Tolkien's Elves.[11] Since all seven appendices and part of the foreword were dropped in the first edition, the rules of transcription therein were not kept. In the New edition Dr. Lottem translated the appendices by himself, and transcribed names according to the instructions therein. Furthermore, the old translation was made without any connection to the rest of Tolkien's mythological context, not The Silmarillion nor even The Hobbit. Parts of the story relating to events mentioned in the above books were not understood and therefore either translated inaccurately, or even dropped completely. There are major inconsistencies in transcription or in repetitions of similar text within the story, especially in the verse.[13]

Tolkien's Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings[edit]

In 1966-67, Tolkien wrote the Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings as a guideline on the nomenclature in The Lord of the Rings, for the benefit of translators, especially those seeking to render the novel into Germanic languages. The first translations to profit from the guideline were those into Danish (Ida Nyrop Ludvigsen) and German (Margaret Carroux); both appeared in 1972.

Frustrated by his experience with Schuchart's Dutch and Ohlmarks's Swedish translations, Tolkien asked that

when any further translations are negotiated, [...] I should be consulted at an early stage. [...] After all, I charge nothing, and can save a translator a good deal of time and puzzling; and if consulted at an early stage my remarks will appear far less in the light of peevish criticisms.

— Letter of 7 December 1957 to Rayner Unwin, Letters, p. 263

With a view to the planned Danish translation, Tolkien decided to take action in order to avoid similar disappointments in the future. On 2 January 1967, he wrote to Otto B. Lindhardt, of the Danish publisher Gyldendals Bibliotek:

I have therefore recently been engaged in making, and have nearly completed, a commentary on the names in this story, with explanations and suggestions for the use of a translator, having especially in mind Danish and German.

— Tolkien-George Allen & Unwin archive, HarperCollins, cited after Hammond and Scull 2005

Photocopies of this "commentary" were sent to translators of The Lord of the Rings by Allen & Unwin from 1967. After Tolkien's death, it was published as Guide to the Names in The Lord of the Rings, edited by Christopher Tolkien in Jared Lobdell's A Tolkien Compass (1975). Wayne G. Hammond and Christina Scull (2005) have newly transcribed and slightly edited Tolkien's typescript, and re-published it under the title of Nomenclature of The Lord of the Rings in their book The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion.

Tolkien uses the abbreviations CS for "Common Speech, in original text represented by English", and LT for the target language of the translation. His approach is the prescription that if in doubt, a proper name should not be altered but left as it appears in the English original:

All names not in the following list should be left entirely unchanged in any language used in translation (LT), except that inflexional s, es should be rendered according to the grammar of the LT.

The names in English form, such as Dead Marshes, should in Tolkien's view be translated straightforwardly, while the names in Elvish should be left unchanged. The difficult cases are those names where

the author [Tolkien], acting as translator of Elvish names already devised and used in this book or elsewhere, has taken pains to produce a CS name that is both a translation and also (to English ears) a euphonious name of familiar English style, even if it does not actually occur in England.

An example is Rivendell, the translation of Sindarin Imladris "Glen of the Cleft", or Westernesse, the translation of Númenor. The list gives suggestions for "old, obsolescent, or dialectal words in the Scandinavian and German languages".

Ida Nyrop Ludvigsen's Danish and Margaret Carroux's German translations were the only ones profiting from Tolkien's "commentary" to be published before Tolkien's death in 1973.

List of translations[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Letters, 305f.; c.f. Martin Andersson "Lord of the Errors or, Who Really Killed the Witch-King?"

- ^ a b c Shippey, Tom (2005) [1982]. The Road to Middle-Earth (Third ed.). Grafton (HarperCollins). pp. 131–133. ISBN 978-0261102750.

- ^ a b c Strömbom, Charlotte (29 January 2009). "God åkermark eller fet och fruktbar mylla? – Om Erik Anderssons och Åke Ohlmarks översättningar av J.R.R. Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings" [Good arable land or fertile and fruitful soil? – On Erik Andersson's and Åke Ohlmarks' translations of J.R.R. Tolkiens The Lord of the Rings]. Vetsaga (in Swedish). ISSN 1654-0786.

- ^ Hooker, Mark T. (2004). "Dutch Samizdat: The Mensink-van Warmelo Translation of The Lord of the Rings". Translating Tolkien: Text and Film. Walking Tree Publishers. pp. 83–92.

- ^ "Newly Revised Dutch Edition of the Lord of the Rings". Archived from the original on 16 February 2008. Retrieved 7 March 2008.

- ^ Tolkien och den svarta magin (1982), ISBN 978-91-7574-053-9.

- ^ Löfvendahl, Bo (30 December 2003). "Vattnadal byter namn i ny översättning" [Waterdale changes name in new translation]. Svenska Dagbladet (in Swedish). Retrieved 7 September 2016.

- ^ "Margaret Carroux". Ardapedia. Retrieved 28 December 2016.

- ^ a b Markova, Olga (2004). "When Philology Becomes Ideology: The Russian Perspective of J.R.R. Tolkien". Tolkien Studies. 1. Translated by Hooker, Mark T.: 163–170. doi:10.1353/tks.2004.0011. S2CID 51684428.

- ^ See also Hooker, Mark T. (2003). Tolkien Through Russian Eyes. Walking Tree Publishers. ISBN 3-9521424-7-6.

- ^ a b The new version, Editor's endnote.

- ^ The second edition therefore soon replaced the older one on the shelves, under the name: "שר הטבעות, תרגמה מאנגלית: רות לבנית. ערך מחדש: עמנואל לוטם ("The Lord of the Rings". Translated by Ruth Livnit, revised by Emanuel Lottem. Zmora Beitan [זמורה ביתן] publication: Tel Aviv, 1991)

- ^ Yuvl Kfir, who assisted Dr. Lottem in the revision, wrote an article in favour of the new edition, translated by Mark Shulson: "Alas! The Aged and Good Translation!" [1]

Bibliography[edit]

- Hammond, Wayne G.; Scull, Christina (2005). The Lord of the Rings: A Reader's Companion. London: HarperCollins. 750-782. ISBN 0-00-720907-X.

- Honegger, Thomas (2011) [2004]. Translating Tolkien: Text and Film. Cormarë series. Vol. 6. Walking Tree Publishers. ISBN 978-3-9521424-9-3.

- Honegger, Thomas; Segura, Eduardo (2011). Tolkien in Translation. Cormarë series. Vol. 4. Zurich: Walking Tree Publishers. ISBN 978-3-9521424-6-2.

- Turner, Allan (2005). Translating Tolkien: Philological Elements in "The Lord of the Rings. Duisburger Arbeiten zur Sprach– und Kulturwissenschaft. Vol. 59. Frankfurt: Peter Lang. ISBN 3-631-53517-1.