Vilnius University

Vilniaus universitetas | |

| |

| Latin: Universitas Vilnensis | |

Former names | Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Jesu (1579) Principal School of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (1783) Principal School of Vilnius (1795) Imperial University of Vilnius (1803) Stephen Bathory University (1919) State University of Vilnius (1944) [1] |

|---|---|

| Motto | Hinc itur ad astra (in Latin) |

Motto in English | From here the way leads to the stars |

| Type | Public |

| Established | 1579 |

| Founder | King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania Stephen Báthory |

Religious affiliation | St. John's Church |

| Endowment | ~US$3.7 million[2] (2023) |

| Budget | ~US$200 million[3] (2022) |

| Chancellor | Raimundas Balčiūnaitis |

| Rector | Rimvydas Petrauskas (lt) |

Academic staff | 3,348 |

| Students | 23,517 |

| Undergraduates | 14,025 |

| Postgraduates | 7,071 |

| 797[4] | |

Other students | 825 (MDs in residency) 1995 (international students) |

| Location | , , 54°40′57″N 25°17′14″E / 54.68250°N 25.28722°E |

| Campus | Urban |

| Colors | Maroon |

| Affiliations | EUA, ARQUS European University Alliance, Santander Network, UNICA, Utrecht Network |

| Website | vu.lt |

| |

Vilnius University (Lithuanian: Vilniaus universitetas) is a public research university, which is the first and largest university in Lithuania, as well as one of the oldest and most prominent higher education institutions in Central and Eastern Europe. Today, it is Lithuania's leading research institution.

The university was founded in 1579 as the Jesuit Academy (College) of Vilnius by Stephen Báthory. It was the third oldest university (after the Cracow Academy and the Albertina) in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth. Due to the failure of the November Uprising (1830–1831), the university was closed down and suspended its operation until 1919. In the aftermath of World War I, the university saw failed attempts to restart it by the local Poles, Lithuanians, and by invading Soviet forces. It finally resumed operations as Polish Stefan Batory University in August 1919.

After the Soviet invasion of Poland in September 1939, the university was briefly administered by the Lithuanian authorities (from October 1939), and then after Soviet annexation of Lithuania (June 1940), punctuated by a period of German occupation after Operation Barbarossa, from 1941 to 1944, when it was administrated as the Vilnius State University. In 1945, the Polish community of students and scholars of Stefan Batory University was transferred to Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń.[5] After Lithuania regained its independence in 1990, following the dissolution of the Soviet Union, it resumed its status as one of the prominent universities in Lithuania.

Established in 1579 in Lithuania’s capital city Vilnius, with a faculty in the second-largest city, Kaunas, and another in the fourth-largest city, Šiauliai. The University is composed of fifteen academic faculties that offer more than 200 study programmes in a wide range of academic disciplines for over 24 000 students.[4] Vilnius University is known for its strong community ties, interaction and participation in additional activities offered by the non-academic departments of the University, such as the Cultural Centre, Health and Sports Centre, Library, Museum, Botanical Gardens, and other institutions.

Since 2016, Vilnius University has been a member of a network of prestigious universities–the Coimbra Group–and since 2019, it has belonged to the European University Alliance (ARQU).The alliance aims to create joint, long-term, sustainable structures and mechanisms for close inter-institutional cooperation in the fields of studies, science and social partnerships.[6] The Vilnius University Foundation was established on 6 April 2016, becoming the first university endowment in Lithuania. The Foundation supports scientific research of the highest quality and the creation of study programmes that correspond to global demands, while encouraging other high added-value projects.[7]

Academics[edit]

Teaching and learning

More than 23,000 students are currently studying in 98 Bachelor’s and 113 Master’s degree programmes, with PhD studies offered in 29 scientific fields. Students can also choose from more than 60 medicine and dentistry residency programmes.

International students may choose from the 56 study programmes in English in such fields as medicine, odontology, business and management, economics, mathematics and informatics, philology, law, and communications. More than 2500 international students are studying at Vilnius University, which is around 10% of all students.[8]

The University also offers joint study programmes together with foreign higher education institutions, like the Arqus joint Master’s programme “European Studies” and “Master in International Cybersecurity and Cyberintelligence”. During these collaborative studies, part of the programme takes place at the University, with the other part taking place at a foreign higher education institution. After the completion of these joint studies, a joint qualification degree can be awarded, if the requirements are met.

Research[edit]

The research areas of Vilnius University are:

- Humanities

- Lithuanian Studies

- Structure and Development of Society

- Biological and Sociopsychological Cognition and the Evolution of Man

- Healthy Mankind, Prevention, Diagnostics and Treatment of Diseases

- Genomics, Biomolecules and Biotechnologies

- Changes in Ecosystems, Protection and Natural Resources

- New Functional Materials and Derivatives

- Theoretical and Condensed Matter Physics

- Laser Physics and Light Technologies

- Fundamental and Applied Mathematics

- Informatics and Information Technologies

More than 1/3 of the PhD theses created in Lithuania are defended at Vilnius University, where over 3,000 research publications are published, and more than 400 research projects are implemented annually. Vilnius University has over 160 research teams, which are acknowledged across the globe.[9] The university offers over 450 customizable R&D services in diverse areas such as life sciences, photonics, IT, and psychology

By attracting targeted funding or using the University’s funds, the University currently represents the country or participates as a partner in the following international research infrastructures: EMBL; EMBC (European Conference on Molecular Biology); Instruct-ERIC (Structural Biology Infrastructure); ELI (Extreme Light Infrastructure); CERN; WAEVE Consortium (Next Generation Spectroscopy Facility for the William Herschel Telescope); and the Biobanks and Biomolecular Resources Research Infrastructure (BBMRI-ERIC). The Semiconductor Technology Centre (PTC) and the Innovative Chemistry (INOCHEM) Centre are currently being developed. In addition to these research infrastructures, the University is actively involved in other research networks, associations and continuous research activities.

The EMBL Partnership Institute was established in the Vilnius University Life Sciences Centre (LSC), based on an agreement concluded in 2020, the main goal of which is to initiate and develop new directions and technologies in relation to genome editing research and applications in LSC, and to promote the application of genome editing technologies in LSC and Lithuanian research and study institutions and businesses.[10][11][12]

From 2021, Vilnius University Business School coordinates and implements Global Entrepreneurship Monitoring (GEM) in Lithuania. GEM is the world's largest survey of the state of entrepreneurship, conducted since 1999.[13]

Vilnius University participates in different national and international research projects such as the EU Seventh Framework Programme, Horizon 2020, COST, EUREKA, CERN, etc. To enhance the interrelation between science and business, Vilnius University has established four open access centres aimed at providing access to available research and laboratory equipment not only to students and researchers but also to representatives of business or to personnel of other institutions of science and research.[14]

Prominent researchers[edit]

Professor Virginijus Šikšnys is recognized for his contributions to the development of CRISPR/Cas9 gene editing technology, often referred to as 'gene scissors'. He currently serves as the Head of the Department of Protein–DNA Interactions at the Institute of Biotechnology, Vilnius University.[15]

Prof. Andrej Spiridonov is famous for the discovery of drivers of evolutionary changes at mega-scale. His latest research suggests that life rather than climate influences diversity at scales greater than 40 million years.[16]

Dr. Mangirdas Malinauskas has been working in laser and optical technologies for more than ten years. At the Laser Research Centre, Dr. M. Malinauskas develops technologies popularly known as ‘4D printing’. Such technologies can produce so-called intelligent objects that can change shape and other properties in response to appropriate conditions: electricity, light, heat, humidity, acidity, solvent composition, etc.[17][18]

Dr. Linas Mažutis is developing microfluidic technologies at Vilnius University Life Sciences Centre. He is a co-founder of two biotech and biomedical companies. The first one, Platelet BioGenesis, is an allogeneic cell therapy company focused on platelet biology, discovering a new category in therapeutics. He has also co-founded a start-up: the biotechnology company Droplet Genomics. The company’ is based on droplet microfluidic technology, enabling the study of single cells and molecules. One year ago, the company attracted an investment of €1 million.[19][20]

In 2004, Prof. Valentina Dagienė has established an International Challenge on Informatics and Computational Thinking called BEBRAS (‘Beaver’) which is implemented in over 60 countries. It is an international initiative aiming to promote informatics (Computer Science, or Computing) and computational thinking among school students at all ages. Participants are usually supervised by teachers who may integrate the BEBRAS challenge in their teaching activities. The challenge is performed at schools using computers or mobile devices.[21][22]

History[edit]

Changes of the name[edit]

The university has been known by many names during its history. Due to its long history of Jewish, Polish and Russian influence or rule, the city portion of its name is rendered as Vilna (Latin), Wilna (German) or Wilno (Polish), in addition to Lithuanian Vilnius (see History of Vilnius).

- 1579–1782: Alma Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Iesu.[23] The Latin name is rendered into English as Jesuit Academy, Jesuit College, or Academy of Vilnius (Vilna/Wilna/Wilno).[24][25][26][27][28][29][30][31][32][33][34][35]

- 1782–1803: Schola Princeps Magni Ducatus Lithuaniae: Principal School of the Grand Duchy of Lithuania (the name was changed 8 years after Third Partition of Poland)[36]

- 1803–1832: Imperatorski Uniwersytet Wileński.[37] Rendered into English as Imperial University of Vilnius (Vilna/Wilna/Wilno)[38][39][40][41][42]

- 1832–1919: Closed, originally by order of Tsar Nicholas I[43]

- 1919–1939: Stefan Batory University[44] (Uniwersytet Stefana Batorego in Poland)

- 1940–1943: Vilnius University[44] (this period encompassed the first Soviet occupation and German occupation)

- 1944–1955: Vilnius State University[39]

- 1955–1990: Vilnius State University of Vincas Kapsukas[45]

- 1971–1979: Vilnius Order of the Red Banner of Labour State University of Vincas Kapsukas (Vilniaus Darbo raudonosios vėliavos ordino valstybinis Vinco Kapsuko universitetas)

- 1979–1990: Vilnius Orders of the Red Banner of Labour and Friendship of Peoples State University of Vincas Kapsukas (Vilniaus Darbo raudonosios vėliavos ir Tautų draugystės ordinų valstybinis V. Kapsuko universitetas)

- 1990–present: Vilnius University

History by period[edit]

Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth[edit]

In 1568, the Lithuanian nobility[46] asked the Jesuits to create an institution of higher learning either in Vilnius or Kaunas. The following year Walerian Protasewicz, the bishop of Vilnius, purchased several buildings in the city center and established the Vilnian Academy (Almae Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Jesu). Initially, the academy had three divisions: humanities, philosophy, and theology. The curriculum at the college and later at the academy was taught in Latin.[46][47] The first students were enrolled into the academy in 1570. A library at the college was established in the same year, and Sigismund II Augustus donated 2500 books to the new college.[46] In its first year of existence the college enrolled 160 students.[46]

On April 1, 1579, Stefan Batory, King of Poland and Grand Duke of Lithuania, upgraded the academy and granted it equal status with the Kraków Academy, creating the Alma Academia et Universitas Vilnensis Societatis Iesu. His edict was approved by Pope Gregory XIII's bull of October 30, 1579. The first rector of the academy was Piotr Skarga. He invited many scientists from various parts of Europe and expanded the library, with the sponsorship of many notable persons: Sigismund II Augustus, Bishop Walerian Protasewicz, and Kazimierz Lew Sapieha. Lithuanians at the time comprised about one third of the students (in 1586 there were circa 700 students), others were Germans, Poles, Swedes, and even Hungarians.[46]

In 1575, Duke Mikołaj Krzysztof Radziwiłł and Elżbieta Ogińska sponsored a printing house for the academy, one of the first in the region. The printing house issued books in Latin and Polish and the first surviving book in Lithuanian printed in the Grand Duchy of Lithuania was in 1595. It was Kathechismas, arba Mokslas kiekvienam krikščioniui privalus authored by Mikalojus Daukša.

The academy's growth continued until the 17th century. The Deluge era that followed led to a dramatic drop in the number of students who matriculated and in the quality of its programs. In the middle of the 18th century, education authorities tried to restore the academy. This led to the foundation of the first observatory in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth (the fourth such professional facility in Europe), in 1753, by Tomasz Żebrowski. The Commission of National Education (Polish: Komisja Edukacji Narodowej), the world's first ministry of education, took control of the academy in 1773, and transformed it into a modern University. The language of instruction (as everywhere in the commonwealth's higher education institutions) changed from Latin to Polish.[48][49][50] Thanks to the rector of the academy, Marcin Poczobutt-Odlanicki, the academy was granted the status of "Principal School" (Polish: Szkoła Główna) in 1783. The commission, the secular authority governing the academy after the dissolution of the Jesuit order, drew up a new statute. The school was named Academia et Universitas Vilnensis.

Partitions[edit]

After the Partitions of Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth, Vilnius was annexed by the Russian Empire. However, the Commission of National Education retained control over the academy until 1803, when Tsar Alexander I of Russia accepted the new statute and renamed it The Imperial University of Vilna (Императорскій Виленскій Университетъ). The institution was granted the rights to the administration of all education facilities in the former Grand Duchy of Lithuania. Among the notable personae were the curator (governor) Adam Jerzy Czartoryski and rector Jan Śniadecki.

The university flourished. It used Polish as the instructional language, although Russian was added to the curriculum.[47][51] It became known for its studies of Belarusian and Lithuanian culture.[51] By 1823, it was one of the largest in Europe; the student population exceeded that of the Oxford University. A number of students, among them poet Adam Mickiewicz, were arrested in 1823 for conspiracy against the tsar (membership in Filomaci). In 1832, after the November Uprising, the university was closed by Tsar Nicholas I of Russia.

Two of the faculties were turned into separate schools: the Medical and Surgical Academy (Akademia Medyko-Chirurgiczna) and the Roman Catholic Academy (Rzymsko-Katolicka Akademia Duchowna). But soon they were closed as well with Medical and Surgical Academy transformed into Medical faculty of University of Kyiv (now Bogomolets National Medical University), and latter one being transformed into Saint Petersburg Roman Catholic Theological Academy (after the October Revolution of 1917 moved to Poland where it became Catholic University of Lublin). The repression that followed the failed uprising included banning the Polish and Lithuanian languages; all education in those languages was halted.

1918–1939[edit]

The first attempts to reestablish scientific institution in Vilnius were made after the 1905 revolution; on 22 October 1906 the Society of Friends of Science in Wilno (TPN) was created by the Polish intelligentsia. After the outbreak of World War I and the German occupation of the city TPN made an attempt to recreate a university with a creation of so-called Higher Scientific Courses.[52] Unfortunately both TPN and the Courses were soon closed by German officials.[52]

Lithuania declared its independence in February 1918. The university, with the rest of Vilnius and Lithuania, was opened three times between 1918 and 1919. The Lithuanian National Council re-established it in December 1918, with classes to start on January 1, 1919. An invasion by the Red Army interrupted this plan. A Lithuanian communist, Vincas Kapsukas-Mickevičius, then sponsored a plan to re-open it as "Labor University" in March 1919 in the short-lived Lithuanian Soviet Socialist Republic (later, Lithuanian–Belorussian Soviet Socialist Republic), but the city was taken by Poland in April 1919. Marshall Józef Piłsudski reopened it as Stefan Batory University (Uniwersytet Stefana Batorego) on August 28, 1919. The city would fall to the Soviets again in 1920, who transferred it to the Lithuanian state after their defeat in the battle of Warsaw. Finally, in the aftermath of the Żeligowski's Mutiny and 1922 Republic of Central Lithuania general election, the Vilnius Region was subsequently annexed by Poland.[53] In response to the dispute over the region, many Lithuanian scholars moved to Vytautas Magnus University in Kaunas, the interwar capital.[54]

The university quickly recovered and gained international prestige, largely because of the presence of notable scientists such as Władysław Tatarkiewicz, Marian Zdziechowski, and Henryk Niewodniczański. Among the students of the university at that time was future Nobel prize winner Czesław Miłosz. The university grew quickly, thanks to government grants and private donations. Its library contained 600,000 volumes, including historic and cartographic items which are still in its possession.[54]

In 1938 the university had:

- 7 institutes

- 123 professors

- 104 scientific units (including two hospitals)

- 3110 students

The university's international students included 212 Russians, 94 Belarusians, 85 Lithuanians, 28 Ukrainians and 13 Germans.[55] Anti-Semitism increased during the 1930s and a system of ghetto benches, in which Jewish students were required to sit in separate areas, was instituted at the university.[56][57] Violence erupted; the university was closed for two weeks during January 1937.[56] In February Jewish students were denied entrance to its grounds.[56] The faculty was then authorized to decide on an individual basis whether the segregation should be observed in their classrooms and expel those students who would not comply.[56] 54 Jewish students were expelled but were allowed to return the next day under a compromise in which in addition to Jewish students, Lithuanian, Belarusian, and "Polish democratic" students were to be seated separately.[56] Rector of the university, Władysław Marian Jakowicki, resigned his position in protest over the introduction of the ghetto benches.[58]

World War II[edit]

Following the invasion of Poland the university continued its operations. The city was soon occupied by the Soviet Union. Most of the professors returned after the hostilities ended, and the faculties reopened on October 1, 1939. On October 28, Vilnius was transferred to Lithuania which considered the previous eighteen years as an occupation by Poland of its capital.[59] The university was closed on 15 December 1939 by the authorities of the Republic of Lithuania.[60] All the faculty, staff, and its approximately 3,000 students dismissed.[61] Students were ordered to leave the dormitories; 600 ended in a refugee camp.[60] Professors had to leave their university flats. Following the Lithuanization policies, in its place, a new university, named Vilniaus universitetas, was created. Its faculty came from the Kaunas University.[60] The new charter specified that Vilnius University was to be governed according to the statute of the Vytautas Magnus University of Kaunas, and that Lithuanian language programs and faculties would be established. Lithuanian was named as the official language of the university.[60] A new academic term started on 22 January; only 13 of the new students had former Polish citizenship.[60]

Polish Law and Social Sciences, Humanities, Medical, Theological, Mathematical-Life sciences faculties continued to work underground with lectures and exams held in private flats until 1944.[62] Polish professors who took part in the underground courses included Iwo Jaworski, Kazimierz Petrusewicz and Bronisław Wróblewski.[62] The diplomas of the underground universities were accepted by many Polish universities after the war. Soon after the annexation of Lithuania by the Soviet Union, while some Polish professors were allowed to resume teaching, many others (along with some Lithuanian professors) who were deemed "reactionary" were arrested and sent to prisons and gulags in Russia and Kazakhstan. Between September 1939 and July 1941, the Soviets arrested and deported nineteen Polish faculty and ex-faculty of the University of Stefan Batory, of who nine perished: Professors Stanisław Cywinski, Władysław Marian Jakowicki, Jan Kempisty, Józef Marcinkiewicz, Tadeusz Kolaczyński, Piotr Oficjalski, Włodzimierz Godłowski, Konstanty Pietkiewicz, and Konstanty Sokol-Sokolowski, the last five victims of the Katyn massacre.[61]

The city was occupied by Germany in 1941, and all institutions of higher education for Poles were closed. From 1940 until September 1944, under Lithuanian professor and activist Mykolas Biržiška, the University of Vilnius was open for Lithuanian students under the supervision of the German occupation authorities.[63] In 1944, many of Polish students took part in Operation Ostra Brama. The majority of them were later arrested by the NKVD and suffered repressions from their participation in the Armia Krajowa resistance.

Soviet period (1945-1990)[edit]

The sovietisation of Vilnius University, which started in the summer of 1940, continued after World War II. Furthermore, the University community suffered some major upheavals during the Nazi occupation. On the order of the Nazi occupying authorities, all Jewish teachers and later all Polish and Jewish students were expelled from the University. Nearly all the Jewish members of the University community subsequently became victims of the Holocaust. In the summer of 1944, a few dozen former University lecturers retreated to the West, in fear of possible repression by the Soviet Regime. The arrests of lecturers started at the beginning of 1945 and continued until Stalin’s death. Even more professors were dismissed on political grounds.

Educated Poles were transferred to People's Republic of Poland after World War II under the guidance of State Repatriation Office. As the result, many former students and professors of Stefan Batory joined universities in Poland. To keep in contact with each other, the professors decided to transfer whole faculties. After 1945, most of the mathematicians, humanists and biologists joined the Nicolaus Copernicus University in Toruń, while a number of the medical faculty formed the core of the newly founded Medical University of Gdańsk. The Toruń university is often considered to be the successor to the Polish traditions of Stefan Batory University.

Many famous scientists ended up on the list of the victims of Stalinist terror, including Antanas Žvironas, Tadas Petkevičius, Levas Karsavinas and Vosylius Sezemanas, among others. During the post-Stalin period, when the classical Vilnius University had been converted into a Soviet university and in 1955 was awarded the name of the Vilnius Order of the Red Banner of Labour State University of Vincas Mickevičius-Kapsukas, there were no more mass repressions against the University community.[64] However, separate cases of political persecution still occurred. One of the best-known cases was that instituted against the Department of Lithuanian Literature that lasted from 1958 to 1961, after which four teachers from the Department were forced to leave the University The 1960s could be considered as a prominent threshold in the historical development of Vilnius University. During that period, the University was finally converted into a typical higher education institution, where priority was given to a specialised and simultaneously ideologised technocratic education rather than to the development of a full-fledged personality. In 1968-1978, the academic town was built in Saulėtekio Alley in Antakalnis, where the Faculties of Physics, Economic, Law and Communication, as well as the majority of the student dormitories are now located[64]

After 1990[edit]

On 12 June 1990, three months after the Restoration of Lithuanian Independence, the Supreme Council of Lithuania-Restoration Seimas approved the Statute of Vilnius University, declaring the autonomy of the University, which was granted by the Law on Science and Studies in 1991.

In 1991, the University signed the Great Charter of European Universities – the main declaration of the academic freedom, rights and responsibilities of European universities – thus expressing its goal to re-shape Vilnius University. Moreover, the study programmes at the University were reorganised into three cycles at the Bachelor, Master and Doctoral (or PhD) level.

In 2016, Vilnius University joined the Coimbra Group, a network of prestigious European universities.[65]

Also in 2016, Vilnius University started the Recovering Memory project. The University recognises its responsibility to remember and evaluate the past, especially the tragic events that took place in the pre-war and post-war Lithuania, particularly at Vilnius University. The aim of the project is to commemorate and pay respect to the members of the Vilnius University community, both staff and students, who were expelled from the university, losing the ability to continue their academic careers or studies, because of the actions of the totalitarian regimes and their local collaborators. The symbolic Memory Diploma of Vilnius University has been established in commemoration of these people.[66]

Vilnius University is a member of The Arqus European University Alliance that brings together the Universities of Granada, Graz, Leipzig, Lyon 1, Maynooth, Minho, Padua, Vilnius and Wroclaw.[67][68]

Structure[edit]

Faculties[edit]

- Business School

- Faculty of Chemistry and Geosciences

- Faculty of Communication

- Faculty of Economics and Business Administration

- Faculty of History

- Faculty of Law

- Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics

- Faculty of Medicine

- Faculty of Philology

- Faculty of Philosophy

- Faculty of Physics

- Institute of International Relations and Political Science

- Kaunas Faculty[69]

- Life Sciences Center

- Šiauliai Academy

Campuses[edit]

The faculties and research institutes of Vilnius University are scattered all over Vilnius, with one faculty in Kaunas, and one in Šiauliai.

Vilnius Old Town

In the central part of Vilnius, where the historical buildings of the University are located, there are faculties of Philology, History, and Philosophy. Part of the central administration and rector‘s office is also located here.

The Institute of International Relations and Political Science and the Department of Organizational Information and Communication Research of Communications faculty are also located in the city centre.

The Faculties of Medicine, Chemistry and Geosciences, and Mathematics and Informatics are also located near the city centre. Near the Faculty of Medicine, M.K. Čiurlionis St. Dormitory Complex is located.

Vilnius, Saulėtekis

Saulėtekis – or “Sunrise valley”– is on the outskirts of Vilnius, where student life is concentrated. The campus on Saulėtekis Avenue is home to the faculties of Economics, Physics, Communication, Law, Business School, and the Life Sciences Center, that started operating in 2016 with laboratories.[70] Scholarly Communication and Information Centre and student dormitories are also located here.

In Saulėtekis, Five-Storey Dormitory Complex and Sixteen-Storey Dormitory Complex are located. Students from the faculties of Physics, Law, Economics, History, Communication, Philology and Philosophy, as well as the Business School, the Life Sciences Centre, the Centre of Oriental Studies, schools of International Relations and Politics, and the Foreign Languages Institute are accommodated here.

Kaunas

For as long as more than 55 years (since 1964), Kaunas Faculty is situated in a Old Town nook near the Aleksotas (otherwise known as Vytautas Magnus) bridge. The premises of the 16th – 17th centuries in the Muitinės Street resemble the ensemble of the longstanding Vilnius University premises.

The Faculty has a staff of scientists, pedagogues and administration. The Faculty is interdisciplinary, i.e. it encompasses study programmes from three different fields of science: Humanities, Social and Physical Sciences (Informatics). The Faculty’s scientists carry out interdisciplinary scientific research.

The Kaunas Faculty offers comprehensive programs across Bachelor, Master, and PhD levels, including after-college and additional studies, integrating modern communication and information technologies to maximize practical skills. Exceptional students engage in the ERASMUS Exchange program for international learning experiences, and graduates can pursue various MA specializations such as Audiovisual Translation, Financial Technology, and International Business Management.

Šiauliai

The beginning of higher education in Šiauliai is considered to be since 1948 when Teacher Institute was established which soon became to be titled Šiauliai Pedagogical Institute. In 1997 Šiauliai Pedagogical Institute has been merged with a faculty of Kaunas Technological University, acting in Šiauliai town, and contemporary Šiauliai University began its activity as an independent higher education school. As of 1 January 2021, Šiauliai University became academic unit of Vilnius University — Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy.[71][72]

Šiauliai Academy also has Dormitory. Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy is suggesting study programmes for Full or Part-time studies in the fields of Humanities, Informatics, Engineering, Mathematics, Social, Educational, Life Sciences, Business and Public Management. Three levels of studies are being implemented in Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy: Bachelor‘s degree (first cycle), Master‘s degree (second cycle) and Doctoral degree (third cycle). University carries out also the studies of Continuing Education, Non-Formal Public Education Programs, Supplementary Studies for the Graduates of the Colleges who intend to study for a Master's degree.

-

Business School

-

Center of Physical Sciences and Technology

-

Faculty of Philology

-

Faculty of Philosophy

-

Faculty of Chemistry and Geosciences

-

Faculty of Mathematics and Informatics

-

Faculty of Medicine

-

Faculties of Physics, Economics and business administration, Law and Communication

-

Institute of International Relations and Political Science

-

Kaunas Faculty

-

Life Sciences Center

-

STEAM centre

-

Student dormitories

Other divisions[edit]

- Botanical garden

- “Romuva” Conference, Seminar and Leisure Centre

- Cultural Centre

- Health and Sport Centre

- Library

- Museum

- Publishing House[73]

Library, Museum and Botanical Garden

Vilnius University Library is an academic library of national significance that was founded back in 1570 in Vilnius. As the earliest academic library in the Baltic region, it has holdings of over five million documents, with about 45 thousand registered users and it employs over 200 people. The library consists of the Central Library and the Scholarly Communication and Information Centre (SCIC), as well as libraries for the faculties and centres. The Central Library still works in the authentic 16th-century premises. 5.1 million publications are kept in the Library. The pride of the Library is its collections of old printed books, manuscripts, old engravings and other special collections. https://www.unesco.org/en/articles/lithuania-historical-collections-vilnius-university-library

The Scholarly Communication and Information Centre (SCIC) is the part of the library, equipped with most advanced technologies and situated on Saulėtekis Avenue.

The Vilnius University Museum started its activities during the University’s 431st anniversary, on 1 April 2010. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/355020469_The_museum_of_the_History_of_Medicine_of_Vilnius_University The basis for the new university museum was the old Vilnius University Museum of Progressive Scientific Thought, which was established in the Church of St. Johnson 16 September 1979. The Vilnius University Museum also consists of the Church of St. Johns Bell Tower, Adam Mickiewicz Museum and the Astronomical Observatory on Čiurlionis Street. The museum organises guided tours, educational activities and events.

Botanical Garden – University’s Botanical Garden has been relocated four times. The first Botanical Garden was arranged in the courtyard of Collegium Medicum (Pilies Street 22) in 1781-1799. The core of the Garden was a collection of plants brought by Professor Jean Emmanuel Gilibert from Grodno. The second Garden flourished in Sereikiškės during 1799-1842. In 1919, the Garden was recreated in the territory of Vingis Manor House (M. K. Čiurliono Street 110) and was then relocated to a suburb in the territory of Kairėnai Manor House in 1974.

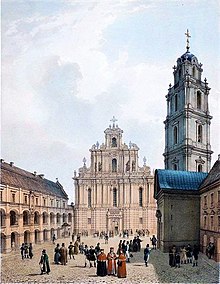

Courtyards

The Vilnius University old ensemble, a significant national architectural heritage complex, remains active in its original educational role. Comprising around thirteen courtyards of varied sizes and significance, it includes:[74][75][76]

- Library Courtyard (Bibliotekos kiemas): Initially a secluded space with various buildings, it evolved in the 19th century to gain a representative role, now housing major parts of the University Library and significant halls.[77]

- Sarbievijus Courtyard (Motiejus Kazimieras Sarbievijus Courtyard): Named after poet and professor Mathias Casimirus Sarbievius, this courtyard, once serving residential and utility functions, features art like Petras Repšys's frescoes and a memorial relief for Baltic tribes.[78]

- Grand Courtyard (Didysis kiemas): The most prominent courtyard, home to the Church of St. Johns and the University Aula, holds historical celebrations, portraits of foundational figures, and the tallest belfry in Vilnius.[79]

- Observatory Courtyard (Observatorijos kiemas): The oldest, dating back to the late 16th century, housed a pharmacy, a printing press, and features the old Astronomical Observatory with the motto "Hinc itur ad astra" (from here one rises to the stars).[80][81]

Ranking[edit]

| University rankings | |

|---|---|

| Global – Overall | |

| ARWU World[82] | 501–600 (2023) |

| QS World[83] | =473 (2024) |

| THE World[84] | 801–1000 (2024) |

| USNWR Global[85] | =801 (2023) |

| Regional – Overall | |

| QS Emerging Europe and Central Asia[86] | 19 (2020) |

| National – Overall | |

| QS National[87] | 72 (2023) |

In the QS World University Rankings 2024, VU ranked 473th among more than one-and-a-half thousand other higher education institutions. VU also ranked 72th position among Nothern Europe universities. Also, Vilnius University ranked 474th in the QS Sustainability ranking.[88]

Vilnius University is ranked 423 among World top universities by 2021 QS World University Rankings. In 2020 QS WU Rankings by Subject, Vilnius University is ranked 201–250 in Linguistics and 251–300 in Physics and Astronomy. In QS rankings of Emerging Europe and Central Asia, Vilnius University is ranked 18.[89]

VU included in the Global QS Rankings and rose by a total of more than 200 positions. When it was first evaluated in 2014, VU ranked 601-650.

Vilnius University is ranked 635 in the world by Best Global Universities Rankings by U.S. News & World Report.[90]

Awards[edit]

- Prof. Saulius Klimašauskas: 1st ERC award winner in Lithuania (Horizon 2020 project “EpiTrack”)[91]

- Galileo Masters prize for technology that allows a big radar system to be installed on a UAV to minimise the costs[92]

- L'Oréal – UNESCO Fellowships for Women in Science: Dr. Rima Budvytytė and Dr. Giedrė Keen, as well as the PhD students Dominyka Dapkutė, Joana Smirnovienė, Milda Alksnė and Greta Jarockytė.[93]

- Prof. Ramūnas Vilpišauskas: winner of the prestigious Jean Monnet Chair position for 2020-2023[94]

- The L’Oréal Baltic For Women in Science International Rising Talents prize winners: Dr Urtė Neniškytė for research on the interaction of neurons and immune cells in the brain, and Dr. Ieva Plikusienė for studies on SARS-CoV-2 protein-antibody interactions

- “Vilnius-Lithuania iGEM”: an award-winning synthetic biology technology development team[95]

- Prof. Virginijus Šikšnys: pioneer in CRISPR/Cas9 technology, and winner of the Kavli Prize in nanosciences, Warren Alpert prize and the Novozymes prize[96]

University Life[edit]

The student life and activities are generally organised within each faculty of Vilnius University.

Student Government[edit]

The Vilnius University Students’ Representation (VU SR) is the oldest and largest non-profit, non-political, expert education organisation in Lithuania representing the interests of students at Vilnius University and beyond.

In total, VU SA has 14 units in each core academic unit (faculty, institute or center) and one Central Office, located in the VU Central Building in the Observatory Courtyard. The organisation has Debate, Photography, Film and Kendo Clubs, as well as an Energy Society and tutors, mentors, “Label-Free” (lith. Be etikečių), “Honestly” (lith. Sąžiningai) and other programmes.[97] Student Government involve more than 1000 active members.

Erasmus Student Network Vilnius University[edit]

Erasmus Student Network (ESN) Vilnius University is a program that promotes student mobility and helps international students integrate at Vilnius University.

Culture Centre and Student Art Groups[edit]

Vilnius University Culture Centre includes 12 art groups, including choirs, orchestras, theatres, ensembles and dance groups. The Centre’s groups participate in Lithuanian and foreign song festivals and international competitions.

Students can join in various art groups such as the Song and Dance Ensemble, Academic Mixed Choir “Gaudeamus” Folk Music Group “Jaunimėlis”, Chamber Orchestra, Kinetic Theatre Troupe, Drama Troupe “Minimum”," Wind Orchestra “Oktava”, Mixed Choir “Pro Musica”," Folk Ensemble “Ratilio”, Girls Choir “Virgo” and the Lindyhop dance group. There are also opportunities to learn to play the organ.[98][99]

The Health and Sports Centre[edit]

The Health and Sports Centre is a department of Vilnius University whose aim is to promote sport and a healthy lifestyle within the community. The Centre offers different sport options for anyone who want to improve their health and sports skills via practice in the gyms and stadium on Saulėtekis Campus and Čiurlionio St., as well as via different health-promoting projects.

The Centre organises interfaculty competitions in 11 sports disciplines. The Health and Sports Centre also trains high-performance athletes to develop their professional sports careers while studying.

Equality, Diversity and Inclusion[edit]

Equal rights at Vilnius University are pursued based on the Diversity and Equality Strategy for 2020-2025, which aims to create a study and work environment where individual, social, and cultural diversity is fostered, and equal opportunities for University community members are ensured. This strategy places particular emphasis on ensuring equal opportunities in the areas of disability, gender equality, different cultures, and social conditions.[100][101]

International relations[edit]

ERASMUS+[edit]

Vilnius University has signed more than 180 bilateral cooperation agreements with universities in 41 countries. Under the Erasmus+ programme the university has over 800 agreements with 430 European universities and 55 agreements with partner country universities for academic exchanges.

University students can actively participate in exchange programmes such as ERASMUS+, ERASMUS MUNDUS, ISEP, AEN-MAUI and CREPUQ.

The University is a signatory of the Magna Charta of European universities and is a member of the International Association of Universities, European University Association, Conference of Baltic University Rectors, Utrecht Network, UNICA Network and the Baltic Sea Region University Network. In addition, Vilnius University has been invited to join the Coimbra Group, a network of prestigious European universities, from 1 January 2016.

ARQUS European University Alliance[edit]

Vilnius University is a founding member of the ARQUS European University Alliance, in which eight comprehensive research universities from across Europe are united.[102][103]

Vilnius University R&D Solutions for Business[edit]

Vilnius University engages in partnerships with businesses and other organizations, providing a variety of research and development (R&D) services. These partnerships aim to convert innovative ideas into practical solutions for business and societal needs. The University's expertise spans multiple disciplines, including natural sciences, medicine, technology, social sciences, and humanities. It offers services such as research collaboration, consultancy, and access to R&D facilities. Vilnius University's approach is to tailor its offerings to meet the specific requirements of each partner, utilizing its research teams to deliver solutions.[104][105][106]

The University is also involved in the fields of entrepreneurship and innovation. It holds a substantial portfolio of patents in life sciences, physical sciences, and technology, with patents registered at various international patent offices. The University establish of over 25 startups and innovative companies. Through its collaborations with entities like the Sunrise Science and Technology Park and Visoriai Information Technology Park, the University supports the development of new ideas and the growth of startup ecosystems. Additionally, its international collaborations and networks provide avenues for companies to explore new partnerships and market opportunities.[107]

People[edit]

Nobel Prize winners[edit]

- Czesław Miłosz, poet, The Nobel Prize in Literature 1980

Notable professors of Vilnius University[edit]

- Alfredas Bumblauskas, professor, historian

- Edvardas Gudavičius, professor, historian

- Henryk Łowmiański, professor, historian

- Lev Karsavin, professor, philosopher, and historian

- Marcin Odlanicki Poczobutt, astronomer

- Šarūnas Raudys, professor, data analyst

- Jan Rustem, professor of painting

- Ferdynand Ruszczyc, professor of painting

- Joseph Saunders (engraver), English printmaker and original professor of art history (1810-1821)

- Piotr Skarga, theologian

- Jan Śniadecki, philosopher and astronomer

- Konstantinas Sirvydas, professor

- Andrius Vaišnys, professor and journalist

- Laima Vaitkunskienė, archaeologist

- Zigmas Zinkevičius, professor, linguist-historian.

Distinguished Guests[edit]

Vilnius University hosted a wide range of distinguished guests including presidents, politicians, and royals, enriching its academic and cultural environment:

- Pope John Paul II: The renowned Pope visited Vilnius University in 1993 during his apostolic journey to Lithuania. His visit was a significant event for both the University and the country, symbolizing the recognition of Lithuania's independence and the Catholic Church's influence.[108]

- King of the United Kingdom Charles III: The Prince of Wales at the time, Charles, visited Vilnius University in 2001.[109]

- Queen of the United Kingdom Elizabeth II and Duke of Edinburgh Prince Philip: The royal couple visited Vilnius University in 2006. During the visit Queen Elizabeth II enthusiastically interacted with the gathered students. Her Majesty inquired about the faculties represented by the students and expressed delight in learning that English Philology was the most popular philological study program. The Duke of Edinburgh, Prince Philip, visited the Botanical Garden of Vilnius University in Kairėnai. The guest arrived for a meeting with participants of the International Award for Young People. Prince Philip created this program in 1956.

- The King of Spain Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofia: Vilnius University had the honor of hosting the King of Spain Juan Carlos I and Queen Sofia in 2009. Their visit underscored the significance of diplomatic relations between Lithuania and Spain. The Royal pair met Spanish students of Vilnius University and Lithuanian students, who learn the Spanish language.[110]

- Dalai Lama: His Holiness the 14th Dalai Lama, the spiritual leader of Tibetan Buddhism, visited Vilnius University in 1991 and again in 2013. His visits were focused on promoting peace, compassion, and interfaith dialogue.[111]

- Robert Huber: The German biochemist and Nobel laureate, Robert Huber, has also graced Vilnius University as a guest in 2017. His visit allowed for discussions on his pioneering work in the field of protein crystallography, furthering the understanding of molecular structures and their functions.[112]

- Emmanuel Macron: President of France Emmanuel Macron visited Vilnius University in 2020. The President had a discussion with University students about the future of global Europe and was rewarded the title of Doctor Honoris Causa of the Vilnius University.[113]

- William Daniel Phillips: Professor William Daniel Phillips, a Nobel Prize winner in Physics and a Distinguished Researcher at the National Institute of Standards and Technology in the United States of America visited Vilnius University in 2022. His visit provided an opportunity for students to engage with his groundbreaking research in the field of laser cooling and atom trapping.[114]

- Katerina Sakellaropoulou: President of Greece Katerina Sakellaropoulou visited Vilnius University in 2022. The President‘s visit highlighted the close historical and cultural ties between Greece and Lithuania. President Katerina Sakellaropoulou's visit contributed to the enhancement of academic and cultural exchanges between Greece and Lithuania.[115][116]

- King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium: The Belgian royal couple visited Vilnius University in 2022. Their Royal Highnesses King Philippe and Queen Mathilde of Belgium visited Life Sciences Centre of Vilnius University and Vilnius University‘s Central Building, where, together with the President of Lithuania Gitanas Nausėda and the First Lady, had an informal encounter with Vilnius University students.[117]

Honorary Doctors of Vilnius University[118][edit]

An honorary doctorate (Doctor Honoris Causa) is a title awarded by universities or other institutions of higher education to individuals for outstanding contributions to the development of activities consistent with the mission of the university. The Vilnius University honorary doctorate has been awarded since 1979. Currently, the University has 68 international honorary doctors, including two Nobel Prize winners and president of France Emmanuel Macron.

- Bruno Robert, Professor, Head of the Department of Bioenergetics, Structural Biology and Mechanisms at Frédéric Joliot Institute for Life Sciences at CEA Paris-Saclay (France) (2022)

- Andrew Bush, Professor, London Imperial College (United Kingdom) (2022)

- Thomas Chung-Kuang Yang, Professor, National Taipei University of Technology (Taiwan) (2022)

- Emmanuel Macron, President of the Republic of France (2020)

- Ian B. Spielman, Professor, National Institute of Standards and Technology (USA) (2020)

- Gérard Mourou Professor, Nobel Prize Laureate, International Center for Zetta-Exawatt Science and Technology (France) (2020)

- Tomas Venclova, Professor, Yale University (USA) (2017)

- Marie-Claude Viano, Professor, Lille 1 University - Science and Technology (France) (2017)

- Otmar Seul, Professor, Paris Nanterre University (France) (2017)

- Peter Schemmer, Professor, University of Heidelberg (Germany) (2016)

- Sanjay Mathur, Professor, Cologne University (Germany) (2016)

- Jón Baldvin Hannibalsson, politician, economist and diplomat (Iceland) (2015)

- Michael Shur, Professor, Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute, (USA) (2015)

- Graham R. Fleming, Professor, University of California Berkeley (USA) (2013)

- Hartmut Fueß, Professor, Darmstadt University of Technology (Germany) (2013)

- Thomas Ruzicka, Professor, Ludwig Maximilian University of Munich (Germany) (2012)

- Markus Wolfgang Büchler, Professor, University of Heidelberg (Germany) (2012)

- Robert Huber, Professor of Biochemistry, Nobel Prize Laureate, director-emeritus of Max-Planck Institute and professor of the Technische Universität in Munich (Germany) (2011)

- Andrzej Gospodarowicz, Professor, Wroclaw University of Economics (Poland) (2011)

- Algis Mickunas, Professor of Philosophy and Phenomenology, Ohio University (USA) (2011)

- Jurij Kuzmenko, Professor of Philology, Humboldt-Universität zu Berlin (Germany) and the Institute for Linguistics Studies of Russian Academy of Sciences (2011)

- Andres Metspalu, Professor of Medicine, Tartu University (Estonia) (2010)

- Imre Kátai, Professor of Mathematics, Budapest Eötvös Loránd University (Hungary) (2010)

- Helmut Kohl, Professor, Johann Wolfgang Goethe University Frankfurt am Main (Germany) (2008)

- Georg Völkel, Professor, University of Leipzig (Germany) (2008)

- Wojciech Smoczyński, Professor, Jagiellonian University in Krakow (Poland) (2007)

- Reinhardt Bittner, Professor, Tubingen University Academic Hospital in Schtutgart (Germany) (2007)

- Gunnar Kulldorff, Professor, Umeå University (Sweden) (2006)

- Jacques Rogge, President of the International Olympic Committee (2006; deceased in 2021)

- Pietro Umberto Dini, Professor, University of Pisa (Italy) (2005)

- Vassilios Skouris, Professor, President of the European Court of Justice (2005)

- Vladimir Skulachev, Professor, Moscow M. Lomonosov University (Russia) (2005)

- Aleksander Kwaśniewski, President of the Republic of Poland (2005)

- Francis Robicsek, Carolinas Heart Institute at Carolinas Medical Centre in Charlotte, North Carolina (USA) (2004; deceased in 2020)

- Peter Gilles, Johan Wolfgang Geothe University (Frankfurt am Main, Germany) (2004; deceased in 2020)

- Peter Ulrich Sauer, Professor, Hanover University (Germany) (2004)

- Sven Ekdahl, Professor, Prussian Secret Archives in Berlin (Germany) (2004)

- Ernst Ribbat, Professor, Münster University (Germany) (2002)

- Jurij Stepanov, Professor, Moscow University (Russia) (2002; deceased in 2012)

- Dagfinn Moe, Professor, Bergen University (Norway) (2002)

- Andrzej Zoll, Professor, Cracow Jagellonian University (Poland) (2002)

- Eduard Liubimskij, Professor, Moscow University (Russia) (2000)

- Wolfgang P. Schmid, Professor, Göttingen University (Germany) (2000; deceased in 2010)

- Sven Lars Caspersen, Professor of Economics, President of the World Rector’s Association, Rector of Aalborg University (Denmark) (1999)

- Ludwik Piechnik, Professor of History, Cracow Papal Theological Academy (Poland) (1999; deceased in 2006)

- Maria Wasna, Doctor, Professor, psychologist, Rector of Münster University (Germany) (1999; deceased in 2019)

- Zbigniew Brzezinski, Professor of government (USA) (1998; deceased in 2017)

- Friedrich Scholz, Director of the Interdisciplinary Institute of Baltic Studies, Professor, Munich University (Germany) (1998)

- Theodor Hellbrugge, founder and Head of the Munich Children Centre, Institute of Social Paediatrics and Adolescent Medicine, Professor, Munich University (Germany) (1998; deceased in 2014)

- Juliusz Bardach, Professor, Warsaw University (Poland) (1997; deceased in 2010)

- Rainer Eckert, Professor, Director of the Institute of Baltic Studies, Greifswald University (1997)

- Nikolaj Bachvalov, Member of the Russian Academy of Sciences, Head of the Computational Mathematics Department, Faculty of Mathematics, Moscow M. Lomonosov University (1997; deceased in 2005)

- Alfred Laubereau, Head of the Experimental Physics Department, Munich Technical University, Professor, Bairoit University (1997)

- Václav Havel, President of the Czech Republic (1996; deceased in 2011)

- Vladimir Toporov, Professor, Institute of Slavonic Languages, Russian Academy of Sciences (1994; deceased in 2005)

- William Schmalstieg, Professor, Pennsylvania University (USA) (1994; deceased in 2021)

- Tomas Remeikis, professor, Indiana Calumet College (USA) (1994; deceased in 2013)

- Paulius Rabikauskas, Professor, Gregorius University (Rome, Italy) (1994; deceased in 1998)

- Martynas Yčas, Professor, New York State University (1992; deceased in 2014)

- Edvardas Varnauskas, Doctor of Medicine, Professor (Sweden) (1992)

- Vaclovas Dargužas (Andreas Hofer), Doctor of Medicine (Switzerland) (1991; deceased in 2009)

- Christian Winter, Professor, Frankfurt am Main University (Germany) (1989)

- Czeslaw Olech, Director of International Mathematical Banach Centre, Member of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Professor, Warsaw University (1989)

- Valdas Voldemaras Adamkus, Administrator of the 5th Regional Environmental Protection Agency, USA (1989)

- Werner Scheler, Professor, Germany (1979)

- Zdenek Češka, Associate Member of the Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Rector of Charles University, Prague (1979)

- Jan Safarewicz, Full Member of the Polish Academy of Sciences, Professor, Cracow Jagellonian University (1979; deceased in 1992)

See also[edit]

- List of early modern universities in Europe

- List of Universities in Lithuania

- Utrecht Network

- Protmušis

- Vilnius University Folklore Ensemble "Ratilio"

- History of Vilnius

- List of Jesuit sites

Lithuania portal

Lithuania portal

References[edit]

- ^ "Universitas Vilnensis 1579-2004" (PDF). vu.lt. Retrieved 31 August 2023.

- ^ "Documents". Vilnius University Foundation.

- ^ "Veiklos dokumentai". Vilniaus universitetas.

- ^ a b "Facts and Figures". Vilnius University. Archived from the original on 2 February 2019. Retrieved 5 August 2023.

- ^ Iłowiecki, Maciej (1981). Dzieje nauki polskiej. Warszawa: Wydawnictwo „Interpress”. p. 241. ISBN 83-223-1876-6.

- ^ "Arqus". Arqus. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ "VU 444 • Congratulate VU with an everlasting birthday gift!". Vilnius University Foundation. Retrieved 14 June 2023.

- ^ "Facts and Figures". www.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Research Activities". www.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "MIMS researchers met members of the Vilnius University EMBL Partnership". projects.au.dk. 19 May 2022. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "CNRS and LT - Presentation INSB-CNRS". PremC. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Partnership Institute of European Molecular ... | Go Vilnius". www.govilnius.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vilniaus universiteto Verslo mokykla ir „Nasdaq Vilnius" tapo strateginiais partneriais". 15min.lt/verslas (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "VILNIUS UNIVERSITY" (PDF). www.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "The most talented students are awarded the first scholarships in the name of Prof. V. Šikšnys". 6 April 2022.

- ^ University, McGill. "Which rules evolutionary change: Life or climate?". phys.org. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Vilnius, Made in (17 July 2019). "The work of a physicist at the Laser Research Center is like an Olympic competition". MadeinVilnius.lt - Vilniaus naujienų dienoraštis. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Mangirdas Malinauskas | WRHI – Tokyo Tech World Research Hub Initiative". www.irfi.titech.ac.jp. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Andrijauskas, Donatas (11 October 2017). "Ein VU-Forscher wird dabei helfen, einen Atlas menschlicher Zellen zu erstellen". MadeinVilnius.lt - Vilniaus naujienų dienoraštis (in German). Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Linas Mažutis: „Tai, ką darome mes, pasaulyje sugeba tik keletas"". www.lrytas.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Dagienė, Valentina; Sentance, Sue (2016). Brodnik, Andrej; Tort, Françoise (eds.). "It's Computational Thinking! Bebras Tasks in the Curriculum". Informatics in Schools: Improvement of Informatics Knowledge and Perception. Cham: Springer International Publishing: 28–39. doi:10.1007/978-3-319-46747-4_3. ISBN 978-3-319-46747-4.

- ^ Dagienė, Valentina; Futschek, Gerald (2008). Mittermeir, Roland T.; Sysło, Maciej M. (eds.). "Bebras International Contest on Informatics and Computer Literacy: Criteria for Good Tasks". Informatics Education - Supporting Computational Thinking. Berlin, Heidelberg: Springer: 19–30. doi:10.1007/978-3-540-69924-8_2. ISBN 978-3-540-69924-8.

- ^ Lithuania Today. Gintaras. 1978. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Lola Romanucci-Ross; George A. De Vos (1995). Ethnic identity: creation, conflict, and accommodation. Rowman Altamira. p. 251. ISBN 978-0-7619-9111-3. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Czesław Miłosz (1983). The history of Polish literature. University of California Press. pp. 114–. ISBN 978-0-520-04477-7. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Antanas Jusaitis; Lithuanian Catholic Truth Society (1918). The history of the Lithuanian nation and its present national aspirations. The Lithuanian Catholic Truth Society. pp. 74–. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Giedrė Mickūnaitė (2006). Making a great ruler: Grand Duke Vytautas of Lithuania. Central European University Press. pp. 156–. ISBN 978-963-7326-58-5. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Norman Davies (May 2005). God's Playground: 1795 to the present. Columbia University Press. pp. 169–. ISBN 978-0-231-12819-3. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 629–. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development; Centre for Co-operation with Non-members (2002). Lithuania. OECD Publishing. p. 201. ISBN 978-92-64-18717-7. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Oskar Halecki (1958). From Florence to Brest (1439-1596). Fordham University Press. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Oskar Garstein (1992). Rome and the Counter-Reformation in Scandinavia: Jesuit educational strategy, 1553-1622. BRILL. p. 236. ISBN 978-90-04-09393-5. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ "JESUITS IN LITHUANIA (A SHORT HISTORY)". Baltic Jesuit advancement project. Archived from the original on 22 July 2011. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Chisholm, Hugh, ed. (1911). . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 28 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 88–89.

- ^ Bain, Robert Nisbet (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 25 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. p. 166.

- ^ Jonas Kubilius (1979). A Short history of Vilnius University. Mokslas. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Akt potwierdzenia Imperatorskiego Uniwersytetu w Wilnie. 1803. Retrieved 20 June 2021.

- ^ Tomas Venclova (2002). Vilnius: city guide. R. Paknio leidykla. ISBN 978-9986-830-48-1. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ a b Soviet physics-collection. Allerton Press. 1979. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Miriam A. Drake (2005). Encyclopedia of library and information science, second edition. CRC Press. pp. 327–. ISBN 978-0-8493-3894-6. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Laimonas Briedis (1 March 2009). Vilnius: city of strangers. CEU Press. ISBN 978-963-9776-44-9. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ Marcel Cornis-Pope; John Neubauer (15 July 2007). History of the literary cultures of East-Central Europe: junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th centuries. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 6–. ISBN 978-90-272-3455-1. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ David H. Stam (1 November 2001). International dictionary of library histories. Taylor & Francis. p. 926. ISBN 978-1-57958-244-9. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b Sarunas Liekis; Šarūnas Liekis (1 January 2010). 1939: the year that changed everything in Lithuania's history. Rodopi. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-90-420-2762-6. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ The Current digest of the Soviet Press. American Association for the Advancement of Slavic Studies. 1955. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ a b c d e Zinkevičius, Zigmas (1988). Lietuvų kalbos istorija (Senųjų raštų kalba) (in Lithuanian). Vilnius: Mintis. p. 159. ISBN 5-420-00102-0.

- ^ a b Kevin O'Connor (2006). Culture and customs of the Baltic states. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 81–. ISBN 978-0-313-33125-1. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Jerzy Jan Lerski (1996). Historical dictionary of Poland, 966-1945. Greenwood Publishing Group. pp. 74–. ISBN 978-0-313-26007-0. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Marcel Cornis-Pope; John Neubauer (13 September 2006). History of the literary cultures of East-Central Europe: junctures and disjunctures in the 19th and 20th centuries. John Benjamins Publishing Company. pp. 19–. ISBN 978-90-272-3453-7. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ Ted Tapper; David Palfreyman (23 December 2004). Understanding mass higher education: comparative perspectives on access. Psychology Press. pp. 141–. ISBN 978-0-415-35491-2. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ a b Piotr Stefan Wandycz (1974). The lands of partitioned Poland, 1795-1918. University of Washington Press. pp. 95–. ISBN 978-0-295-95358-8. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ a b Magdalena Gawrońska-Garstka, Uniwersytet Stefana Batorego w Wilnie. Uczelnia ziem północno-wschodnich Drugiej Rzeczypospolitej (1919-1939) w świetle źródeł, Poznań 2016 p. 17

- ^ Aleksander, Srebrakowski (1993). "Sejm Wileński 1922 roku. Idea i jej realizacja - Repository of University of Wroclaw". HST 25347 99.

- ^ a b Tomas Venclova (Summer 1981). FOUR CENTURIES OF ENLIGHTENMENT: A Historic View of the University of Vilnius, 1579-1979. Lituanus. Retrieved 13 January 2009.

- ^ Aleksander Srebrakowski, Litwa i Litwini na USB Archived 2020-07-16 at the Wayback Machine, Aleksander Srebrakowski, Białoruś i Białorusini na Uniwersytecie Stefana Batorego w Wilnie Archived 2020-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ a b c d e Emanuel Melzer (1997). No way out: the politics of Polish Jewry, 1935-1939. Hebrew Union College Press. pp. 74–76. ISBN 978-0-87820-418-2. Retrieved 10 March 2011.

- ^ "A. Srebrakowski, Sprawa Wacławskiego, "Przegląd Wschodni" 2004, t. IX, z. 3(35), p. 575-601" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 16 July 2020. Retrieved 26 December 2020.

- ^ Ludwik Hass (1999). Wolnomularze polscy w kraju i na śwíecíe 1821-1999: słownik biograficzny. Rytm. p. 183. ISBN 978-83-87893-52-1. Retrieved 11 March 2011.

- ^ D. Trenin. The End of Eurasia: Russia on the Border Between Geopolitics and Globalization. 2002, p.164

- ^ a b c d e Sarunas Liekis; Šarūnas Liekis (1 January 2010). 1939: the year that changed everything in Lithuania's history. Rodopi. pp. 174–175. ISBN 978-90-420-2762-6. Retrieved 9 March 2011.

- ^ a b Adam Redzik, Polish Universities During the Second World War, Encuentros de Historia Comparada Hispano-Polaca / Spotkania poświęcone historii porównawczej hiszpańsko-polskiej conference, 2004

- ^ a b (in Polish) Mikołaj Tarkowski, Wydział Prawa i Nauk Społecznych Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego w Wilnie 1919-1939, - przyczynek do dziejów szkolnictwa wyższego w dwudziestoleciu międzywojennym Archived 2008-02-27 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "History" (PDF).

- ^ a b "Страны мира". Countries. Archived from the original on 3 March 2016. Retrieved 31 May 2015.

- ^ "The CG welcomes Vilnius University | Coimbra". www.coimbra-group.eu. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Bridging Heritage and History: A Conversation with Joslyn Felicijan | American Councils". www.americancouncils.org. 27 November 2023. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "UNICA members in European Universities Alliances | UNICA". www.unica-network.eu. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vilnius University". Arqus. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Vilnius University Kaunas Faculty

- ^ "Inforegio - Life Sciences Centre in Lithuania provides exciting opportunities for students and researchers". ec.europa.eu. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Šiaulių universitetas tapo Vilniaus universiteto Šiaulių akademija". Delfi mokslas (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vilnius University Šiauliai Academy | Academic Influence". academicinfluence.com. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Faculties, Institutes, Centres & Other Departments". Retrieved 18 July 2018.

- ^ "University Ensemble". www.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Ensemble Of Vilnius University | Book Ensemble Of Vilnius University Tour Packages - Travelolithuania". travelolithuania. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vilnius University 2004" (PDF).

- ^ "Library Courtyard". biblioteka.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "M. K. Sarbievius Courtyard". biblioteka.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Andrijauskas, Donatas (27 June 2020). "The 8 most interesting courtyards of the Old Town". MadeinVilnius.lt - Vilniaus naujienų dienoraštis. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Observatory Courtyard". biblioteka.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Klimka, L. (1 December 2003). "Overview of the History of Vilnius University Observatory". Open Astronomy. 12 (4): 649–656. doi:10.1515/astro-2017-00101. ISSN 2543-6376.

- ^ "2023 Academic Ranking of World Universities". Shanghai Ranking. Retrieved 6 April 2024.

- ^ "QS World University Rankings: Lithuania". Top Universities. 29 June 2023. Retrieved 29 June 2023.

- ^ "World University Rankings 2024: Lithuania". Times Higher Education (THE). 28 September 2023. Retrieved 28 September 2023.

- ^ U.S. News. "Best Global Universities in Lithuania". Retrieved 27 February 2024.

- ^ "Vilnius University Rankings".

- ^ "Vilnius University". Top Universities. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vilnius University". Top Universities. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vilnius University". Top Universities. 16 July 2015. Retrieved 31 August 2020.

- ^ "Vilnius University Rankings".

- ^ "Ending long wait, Lithuania lands first European Research Council grant". Science|Business. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "GNSS and SatCom for Multipurpose Lightweight UAV with Radar". Galileo Masters. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Women scientists: what challenges arise, and how can we encourage women to stay on the path of science?". www.lrytas.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Ramūnas Vilpišauskas". www.vle.lt (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Vilnius University Students Achieve Second Place at iGEM: Pioneering Advances in Synthetic Biology".

- ^ "Dr Ieva Plikusienė ranked among globally recognized future talents".

- ^ "Programs, clubs and projects - VU SA". www.vusa.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Dudeniene, Audre (9 June 2021). "The Culture Center of Vilnius University". ArcGIS StoryMaps. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "folk music group "Jaunimėlis"". www.kultura.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Jelena (6 December 2019). "Experience of the Vilnius University in promoting diversity and equal opportunities". www.genderportal.eu. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Lithuania | European Institute for Gender Equality". eige.europa.eu. 15 April 2024. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "The Alliance". Arqus. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Arnaldo Valdés, Rosa María; Gómez Comendador, Victor Fernando (January 2022). "European Universities Initiative: How Universities May Contribute to a More Sustainable Society". Sustainability. 14 (1): 471. doi:10.3390/su14010471. ISSN 2071-1050.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: unflagged free DOI (link) - ^ "Vilnius University". Startup Lithuania. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "UNITeD". EIT HEI Initiative. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "R&D Infrastructure and Services". www.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Park, Visoriai Information Technology. "Visoriai Information Technology Park Non Profit Partner". Up2Europe. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Saint John Paul II visit in Lithuania". City of Mercy. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Team, Editorial (6 November 2001). "Prince Of Wales Charles Arrives In Vilnius Tuesday". PravdaReport. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "News.lt". www.news.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Dalai Lama to give lecture at Vilnius University, to hold press conference". Delfi EN (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Andrijauskas, Donatas (3 July 2017). "A Nobel Prize laureate is coming to Vilnius University". MadeinVilnius.lt - Vilniaus naujienų dienoraštis. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "French president receives honourary doctorate degree from Vilnius University". lrt.lt. 29 September 2020. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ Vilnius, Made in (2 October 2022). "William Daniel Phillips, laureate of the Nobel Prize in Physics, is coming to Vilnius University". MadeinVilnius.lt - Vilniaus naujienų dienoraštis. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "The President of Greece will visit Vilnius – Baltics News". Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "President of Greece Visits Vilnius University". www.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Belgian royal couple starting state visit to Lithuania". Delfi EN (in Lithuanian). Retrieved 24 April 2024.

- ^ "Honorary Doctors". www.vu.lt. Retrieved 24 April 2024.

Bibliography[edit]

- Studia z dziejów Uniwersytetu Wileńskiego 1579–1979, K. Mrozowska, Kraków 1979.

- Uniwersytet Wileński 1579–1979, M. Kosman, Wrocław 1981.

- Vilniaus Universiteto istorija 1579–1803, Mokslas, Vilnius, 1976, 316 p.

- Vilniaus Universiteto istorija 1803–1940, Mokslas, Vilnius, 1977, 341 p.

- Vilniaus Universiteto istorija 1940–1979, Mokslas, Vilnius, 1979, 431 p.

- Łossowski, Piotr (1991). Likwidacja Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego przez władze litweskie w grudniu 1939 roku (in Polish). Warszawa: Interlibro. ISBN 83-85161-26-0.

External links[edit]

Media related to Vilnius University at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Vilnius University at Wikimedia Commons- Official website

- Institute of International Relations and Political Science

- Universitas Vilnensis 1579-2004, well written and illustrated book (92 pages)

- History of Vilnius University by Tomas Venclova

- (in Lithuanian) Vilniaus universitetas (reprezentacinis leidinys)

- (in Polish) Uniwersytet Wileński 1579-2004 Archived 2016-03-03 at the Wayback Machine

- (in Polish) A. Srebrakowski, Studenci Uniwersytetu Stefana Batorego w Wilnie. 1919-1939, Wrocław 2008 – part one Archived 2020-07-16 at the Wayback Machine

- Vilnius University Students' Representation

- Vilnius University Cyber Security Competition "VU Cyberthon"

- Vilnius University

- Universities in Lithuania

- Defunct universities and colleges in Poland

- Educational institutions established in the 1570s

- 1579 establishments in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Public universities

- 1579 establishments in Lithuania

- Universities and colleges in the Polish–Lithuanian Commonwealth

- Legal education in Lithuania

- Universities and colleges in Lithuania

- Education in Vilnius