Vorkutlag

The Vorkuta Corrective Labor Camp (Russian: Воркутинский исправительно-трудовой лагерь, tr. Vorkutinsky ispravitel'no-trudovoy lager'), commonly known as Vorkutlag (Воркутлаг), was a major Gulag labor camp in the Soviet Union located in Vorkuta, Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic, Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic from 1932 to 1962.

The Vorkutlag was one of the largest camps in the Gulag system, the camp housed 73,000 prisoners at its peak in 1951, containing Soviet and foreign prisoners including prisoners of war, dissidents, political prisoners ("enemies of the state") and common criminals who were used as forced labor in the construction of coal mines, coal mining works, and forestry. The camp was administered by the Joint State Political Directorate from 1932 to 1934, the NKVD from 1934 to 1946 and the Ministry of Internal Affairs (Soviet Union) from 1946 until its closure in 1962. The Vorkuta Gulag was the site of the Vorkuta Uprising in July 1953.

History[edit]

Establishment of Vorkutlag, 1930–1932[edit]

Large coal fields were discovered in the Pechora area in the early 19th century, it was discovered by T.C Bornovolokov in 1809 and various other geologists and explorers from 1828 to 1866. E.K Hoffman, a wealthy entrepreneur, wanted to develop the area for coal mining but couldn't as there were no funds for it.[1][2] In 1930 the geologist Georgy Chernov (1906–2009) discovered substantial coal fields by the river Vorkuta. Chernov's father, the geologist Alexander Chernov (1877–1963), promoted the development of the Pechora coal basin and wrote about it in 1924, which included the Vorkuta fields.[3][4] With this discovery the coal-mining industry started in the Komi ASSR. (At the time only the southern parts of the field were included in the Komi ASSR. The northern part, including Vorkuta, belonged to the Nenets Autonomous Okrug of Arkhangelsk Oblast.) In 1931 a geologist settlement was established by the coal field, with most of the workers being inmates of the Ukhta-Pechora Gulag camp. The Vorkuta camp was established by Soviet authorities a year later in 1932 for the expansion of the Gulag system and the discovery of coal fields by the river Vorkuta, on a site in the basin of the Pechora River, located within the Komi ASSR of the Russian SFSR (present-day Komi Republic, Russia), approximately 1,900 kilometres (1,200 mi) from Moscow and 160 kilometres (99 mi) above the Arctic Circle. The town of Vorkuta was established on 4 January 1936 to support the camp, which was constructed to exploit the resources of the Pechora Coal Basin, the second largest coal basin in the Soviet Union. The camp was constructed mainly for Coal Mining and Forestry, There were approximately 132 sub-camps in the Vorkuta Gulag system during the height of its use in the Soviet prison system. Town status was granted to Vorkuta on November 26, 1943.[3]

Trotskyist uprising of 1936[edit]

In the 1930s, Vorkuta was used temporarily as a camp for forced labour and "re-educating" political dissidents, especially Trotskyists. Most of Leon Trotsky's followers and supporters were sent away to the Gulags in Siberia, were executed, or were exiled by Joseph Stalin as a part of the Great Purge which started in August 1936. The purges and convictions of Trotsky's followers, Mensheviks, and other party factions started long before the Great Purge, but the killings and convictions were ramped up as Stalin grew more suspicious of the high-ranking members of the party. On 27 October 1936, Trotskyist prisoners started a hunger strike and a small uprising which turned into a very long and large one. Ivan Khoroshev, who made a report on the uprising and strike, wrote: “In the mid and late 1930s, the Trotskyists in Vorkuta were a very patchwork group; some of them still called themselves Bolshevik-Leninists.” Khoroshev estimates that the “genuine Trotskyists” numbered “almost 500 at the Vorkuta mine, close to 1,000 at the camp of Ukhta-Pechora, and certainly several thousands altogether around the Pechora district.” This report wouldn't reach the west until 1961.[5]

According to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, the strikers demanded, among other things, “separation of the politicals from the criminals, an eight-hour workday, the restoration of the special ration for politicals, and the issuing of rations independently of work performance”.[6] In his own account, Khoroshev's summary of the demands is similar, except for the one concerning special rations. According to Khoroshev, the hunger strikers insisted only that “the food quota of the prisoners should not depend on their norm of output. A cash bonus, not the food ration, should be used as a productive incentive”. On 8 March 1937, after 132 days of protesting and going on strike, the strikers received a “radiogram from the headquarters of the NKVD, drawn up in these words: ‘Inform the hunger strikers held in the Vorkuta mines that all their demands will be satisfied’”. The strike lasted for five months, which is considered the longest uprising that happened in the Gulag system. It ended as a victory for the Trotskyist strikers.[5] Soon after the strike ended, most of the political dissidents, including the Trotskyists in the camps and around the Soviet Union, would be executed in the Great Purge. An anonymous survivor of Vorkuta wrote an account that claimed there was another hunger strike which happened in 1934, before the Trotskyist uprising. That strike ended in a victory as well.[5][7]

Vorkutlag, 1932–1961[edit]

About 102 prisoners were housed in the camp, most were transported from the nearby camps Inta, Ukhta and others in 1932 and soon went up to 332 prisoners. In 1937 the construction of the Pechora Mainline started,[8] the new railway was an addition to the Northern Railway (Russia) which connected Moscow to Vorkuta, Konosha, Kotlas, the camps of Inta and other Northern parts of European Russia. The Railway was built by tens of thousands of prisoners from the Vorkutlag and other nearby Gulags and was completed in 1941, the first train in Vorkuta arrived on 28 December

1941, this important event was attended by residents of Vorkuta and photographed by Fomin Yakov Yakovlevich who was in charge of constructing the railway. From 1939, Polish prisoners were held at Vorkuta following the Occupation of Poland[9] until the German invasion of the Soviet Union in 1941.[10] Vorkuta was then also used to hold German prisoners of war captured on the Eastern Front in World War II as well as criminals,[11] Soviet citizens and those from Soviet-allied countries deemed to be dissidents and enemies of the state during the Soviet era, US soldier were also held in the camp, a majority of whom were captured from the Korean War.[12] Many prisoners didn't survive in the camp and died by freezing to death in the cold climate, dying from starvation as food was scarce in Vorkuta, or the inmates worked themselves to death. Prisoners were given rye bread, buckwheat, a little meat and fish and potatoes as food but in very small amounts, Prisoners resorted to killing rats or stray dogs for food. Self-harm was common in the camp, if an inmate sustained an injury they would be sent to the hospital where conditions were better. The average amount of working time in the camp was 16 hours a day for every inmate.[13] The guards who protected and managed the Gulag were a part of the NKVD, MVD and the Red Army. Guards were most often recruited on three-year contracts after completing their basic military service. Regulations allowed guards to shoot without warning any prisoner who strayed outside the designated work zone or too near a camp fence.[14]

Vorkutlag during World War II[edit]

Working conditions[edit]

Working conditions during World War II were especially brutal. Working hours were increased from eight to ten hours for non-prisoners, and from ten to twelve hours for prisoners.[15] A nationwide lack of food because of compromised farmland and the mass diversion of food to the Red Army meant that feeding Gulag prisoners was not a high priority. In 1943 and 1944, the majority of Vorkutlag prisoners lived on the cusp of starvation. The death rate of the Gulag system as a whole rose as well. In 1939 and 1940, the death rates were 38.3 per thousand prisoners, and 34.7 per thousand prisoners respectively. In 1941, this rose to 67.3/thousand, in 1942 to 175.8/thousand, and in 1943, 169.7/thousand.[16]

Coal production[edit]

As a significant producer of coal, Vorkutlag played a major role in the Soviet Union's war economy, supplying the factories of the war machine. Because of Germany's initial strides in the war, the Soviet Union's major coal supplier was Ukraine. By the end of 1941, the Nazi army had occupied

virtually all of Ukraine, cutting Soviet coal production in half.[15] In 1943 the Vorkutlag's prisoner population exploded, as did the rate of coal extraction. On March 17, 1943, the importance of Vorkutlag coal was underscored with the replacement of camp director Leonid Tarkhanov with Engineer-Colonel (and later Major-General) Mikhail Maltsev. Maltsev was personally selected by NKVD director Beria to oversee the camp's production.[15]

Maltsev utilized his military experience to drastically increase production. He increased the working hours of both prisoners and non-prisoners, and to improve discipline, rewarded hard-working prisoners and punished their opposites.[15] Typically, a reward for hard work would come in the form of an early release, while punishments were usually execution.

The growth of coal production in Vorkuta during Maltsev's tenure from 1943 to 1947 was tremendous. Over this five-year period yearly coal output more than doubled. From 1940 to 1948, the year after Maltsev left Vorkuta, yearly coal production increased eighteen-fold.[15] This is due not only to Maltsev's administration, but also to the large investment by the Soviet government into the camp.

Importance to Leningrad[edit]

The city of Leningrad, during the Siege of Leningrad - the longest siege of the Second World War - was a major customer of Vorkutlag coal. Following the collapse of the Don and Moscow coal basins in Ukraine, Vorkuta became the nearest coal source to Leningrad, which experienced an almost total blockade from September 1941 to January 1944. The widespread coal scarcity across the Soviet Union, and specifically the dire requirement in Leningrad, instilled a pressing need to expedite the expansion of the Vorkuta coal infrastructure. Vorkutlag's coal was a vital source of energy for the encircled Leningrad.[17]

Lesoreid uprising, 1942[edit]

The armed Lesoreid uprising began on January 24 in the Lesoreid lagpunkt (Russian: лагпункт «Лесорейд») of Vorkutlag, a remote logging camp. The uprising involved over 100 prisoners and non-prisoners. Led by the non-prisoner chief of Lesoreid, Mark Retyunin, the rebels aimed to capture the nearby small town of Ust-Usa, though their ultimate goal remains unclear. Retiunin and his group disarmed and overpowered the camp guards, then invited other prisoners to join the uprising. They acquired food, equipment, and clothing from the camp storehouses before heading towards Ust-Usa.[17]

The rebels successfully attacked the town's communication office, State Bank, NKVD office, and jail, freeing prisoners in the process. However, they were repelled at the airfield and faced a fierce battle at the local militia office. Reinforcements, including militarized guards from the nearby Polia-Kur'ia camp section, forced the rebels to retreat from Ust-Usa.[17]

Forty-one rebels fled on sleds, attempting to reach Kozhva, the nearest station on the Northern Pechora Mainline. Along their journey, they acquired more supplies and weapons from various sources, including an arms convoy. Despite their efforts, the rebels realized they were being pursued and changed their course to head west down the Lyzha River.[17]

Government forces, led by Deputy Narkom and Obkom Second Secretary Vazhnov, engaged in several encounters with the rebels, with casualties on both sides. The main group of rebels, led by Retiunin, was defeated on February 2, and several rebels chose to take their own lives instead of being captured. The last group of rebels was captured on March 4. In total, 48 rebels were killed, and eight were captured.[17]

Vorkuta Uprising, 1953[edit]

The Vorkuta uprising occurred in Vorkuta at the Rechlag from 19 July 1953 to 1 August 1953, when inmates from various camp detachments who were forced to work in the region's coal mines went on strike. The uprising—initially in the form of a passive walkout—began on or before July 19, 1953, at a single "department" and quickly spread to five others. Initial demands—to give inmates access to a state attorney and due justice—quickly changed to political demands. Even without foreign assistance, strikes at nearby sites were clearly visible as the wheels of the mine headframes stopped rotating, and word was spread by trains, which had slogans painted by prisoners on the sides, and whose crews spread news. The total number of inmates on strike reached 18,000. The inmates remained static within the barbed wire perimeters.[18][19][20] For a week following the initial strike the camp administration apparently did nothing; they increased perimeter guards but took no forceful action against inmates. The mines were visited by State Attorney of the USSR, Roman Rudenko, Internal Troops Commander, Ivan Maslennikov, and other top brass from Moscow. The generals spoke to the inmates who sat idle in camp courtyards, peacefully. However, on July 26 the mob stormed the maximum security punitive compound, releasing 77 of its inmates. The commissars from Moscow remained in Vorkuta, planning their response. The inmates demanded lower production targets, wages and to be allowed to write more than two letters a year. Concessions were made, including being allowed to write more than two letters a year and to be allowed one visitor a year but the inmates demanded more. On July 31 camp chief Kuzma Derevyanko started mass arrests of "saboteurs"; inmates responded with barricades. The next day, on August 1, after further bloodless clashes between inmates and guards, Derevyanko ordered direct fire at the mob resulting in the deaths of at least 53 workers and injuring 135 (many of them, deprived of medical help, died later) although estimates vary. According to Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn, there were 66 killed. Among those shot was the Latvian Catholic priest Jānis Mendriks.[21][22]

Closing of Vorkuta camp, 1962[edit]

The Vorkuta camp was liquidated by order of the USSR Ministry of Internal Affairs and eventually closed in 1962, the closure of Gulags started when Nikita Khrushchev came into power, Khrushchev started a series of reforms known as De-Stalinization which caused the closure of most Gulags. Vorkuta became one of the most well known Gulags, it gained a reputation of being one of the worst in the Soviet Union. About two million prisoners had gone to Vorkutlag from 1932 until the closure in 1962, the number of deaths in the camp was estimated to be 200,000. Most prisoners were released after the closure of Vorkuta but large numbers of Soviet citizens who were former prisoners remained living in Vorkuta, either due to the restrictions on their settlement or their poor financial situation, or having nowhere to go. Memorial, a Russian human rights organization that focuses on recording and publicising the human rights violations of the Soviet Union's totalitarianism,[23] estimates that of the 40,000 people collecting state pensions in the Vorkuta area, 32,000 are former Gulag inmates or their descendants.[24]

Location[edit]

Vorkuta Gulag camp was located in Vorkuta, Komi Autonomous Soviet Socialist Republic in the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic, Soviet Union. It was 160 km above the arctic circle and roughly 50 km from the Ural mountain range. The town and the camp were located in the North Eastern part of the Komi ASSR 8 km (4.9 mi) below the urban locality of Oktyabrskii (Октябрьский), 13 km (8 mi) West of the village Sovetsky (Советский) and 14 km (8.6. mi) East of Zapolyarny (Заполярный). The surrounding localities, villages, towns and lands were all located in one larger district called Vorkuta City or Vorkuta District (город Воркута) which made up the whole Northeastern tip of the Komi ASSR. Komi ASSR and Vorkuta City are located in the very northern part of European Russia.

Climate[edit]

Vorkuta was extremely cold since it was located in the very northern part of European Russia in the Arctic Circle. The average temperatures from winter to summer being -25 °C (-13 °F) to 18 °C (64.4 °F) and reaching as low as −52 °C (−61 °F) Vorkuta has a subarctic climate (Köppen Dfc) with short cool summers and very cold and snowy winters. Midnight sun or "Polar Day" was common in Vorkuta where the sun wouldn't set for three months, it lasted from 30 May to 14 July, Vorkuta also had Polar night. The polar night lasted from 17 December to 27 December which greatly affected the prisoners in Vorkutlag, prisoners weren't given good enough clothing to survive the climate and many froze to death.

The average February temperature is about −20 °C (−4 °F), and in July it is about +13 °C (55 °F).[25] Vorkuta's climate is influenced both by its distance from the North Atlantic and the proximity to the Arctic Ocean, bringing cold air in spring.

Vorkuta in the present day[edit]

Vorkuta is now a town in the Komi Republic, Russia.[26] The remains of the Gulag camps are abandoned and partly or almost entirely destroyed. Vorkuta is heavily declining in population and is slowly being abandoned, after the Dissolution of the Soviet Union, Mining companies moved farther into the southern regions of Russia. The majority of the population in Vorkuta worked in the nearby coal mines, after the coal mine companies moved many lost jobs and started moving out of Vorkuta. The estimated population in 2019 was about 50,000 and is still decreasing.[27][28]

Inmate accounts of Vorkutlag[edit]

John H. Noble[edit]

In the 1930s the Noble family, a family of German Americans living in Detroit, returned to Dresden, Germany to start operating a camera factory. During World War II, the Noble family tried to leave Germany but were denied by the Gestapo, and the factory was taken over by the East German government. John H. Noble and his father Charles A. Noble were arrested by the Stasi to keep them from protesting the takeover, Noble was never charged with any crime but was still sent to the Gulag system. Noble wrote in his accounts "My life in Vorkuta was the closest thing possible to a living death. It was a grueling combination of slow but continuous starvation, exhausting work, killing cold, and abject monotony that destroyed many a healthier man than I. There was no wasted time in Vorkuta. I went to work producing coal for the Reds the day I got there. My job was to push a two-ton car full of slate by hand. I worked on the surface that first year in the worst Vorkuta winter in a decade. After morning mess, I lined up in excruciating thirty-five-below-zero cold. My job was a mile and a half away from the camp. Fifty of us, covered by ten guards and two police dogs, made the trip every morning through a forty foot wide corridor. About twenty guard towers were alternately spaced on either side of the corridor."

Noble further wrote about the daily suffering in Vorkutlag “Three days passed and no food was distributed to us. At last on the fourth day a few ounces of bread and some thin soup were handed to me; on the fifth day, more of the same, but as I lay down that evening I had no idea that on the following morning would begin a twelve-day starvation period. When it became apparent on the first of those days that there was to be no food, loud protests, uncontrolled curses and screaming were let loose. Men went out of their minds, women prisoners became hysterical. Some Moslem prisoners chanted their prayers. Then death struck, right and left. Cell doors were opened and dead bodies pulled out by an arm or a leg. Some seven hundred prisoners had entered that starvation period. I was one of twenty-two or twenty-three that survived, along with my father". Noble also wrote about his survival in the Gulag “Learning Russian was my first survival project. My teacher was a barracks mate, Ivan, a former student at Moscow University, one of the many disgruntled Soviet intellectuals. Without realizing it, I had already picked up a few words on the slate job – ‘pull,’ ‘stop,’ and others from the guards commands. In no time I was making excellent progress. I worked at it every spare minute, and in a short time could speak halting, grammatically poor Russian. Now that I was out of my cocoon, my circle of friends grew rapidly. My new friends made life a little more bearable. I shared in their meager food packages sent from home. Sometimes a friend in the kitchen would find a little extra cabbage soup or fat to help protect my 95 pounds against the cold. When I went to the camp hospital later, my friends brought me bread saved from their own rations.” Nobles release, “Early in June, I was eating my cabbage soup in the stolovaya [cafeteria] when the nevalney, my barracks master, rushed in excitedly. ‘Americanitz, the camp commander is looking for you. You have orders to proceed to Moscow.’ I looked up at him and laughed in my soup. A few minutes later, a friend came in with the same news. I rushed nervously to the Administration Building and stood at attention before MVD Lieutenant Antrashkevich. ‘You are to leave for Moscow at 7 A.M.,’ he said. ‘As far as I know, you're going home.’ I heard him, but the words didn't sink in. I wouldn't let them. The thought was wild. Why should I be released? There was no general amnesty. I had so lost touch with the world that Vorkuta and its regulations were the only reality I understood. But I prayed, just in case”.[29]

Edward Buca[edit]

Edward Buca was a soldier in the Polish Home Army, the Polish underground resistance movement in German-occupied Poland, Buca was arrested with a group of other soldiers for alleged treason to the Soviet Union. He spent thirteen years in the Gulag working in Vorkuta, “We were marched to the site of the new mine: no. 20. The mine already in operation was no. 19, and both were surrounded by barbed-wire fences with watch-towers at each corner. When we arrived at the site, some of our guards went to man the towers and the rest stayed with us. Some of us were given picks and shovels, others crowbars, heavy sledgehammers weighing about ten kilos, axes or saws. We were divided into work brigades each with different assignments: clearing snow where the smithy was to be built, preparing the site for the instrumentalka or toolshop, sawing planks for the buildings. A desetnik, or civilian foreman, was in charge. He was to be a department chief of the new mine".

Buca wrote about the labor in Vorkuta: “The hard work in the arctic cold and the poor food wore away our energy and our health. After only three weeks most of the prisoners were broken men, interested in nothing but eating. They behaved like animals, disliked and suspected everyone else, seeing in yesterday's friend a competitor in the struggle for survival. When work brigades returned to the camp and formed up at the gate you could see only rows of yellow-grey faces, rimmed with snow and ice, their eyes leaking tears which froze on their cheeks. These weren't normal tears, but were caused by the bitter cold and the feeling of hopeless desperation. This feeling limited our horizons to the thought of the next meal and the chance of getting a little warmer. At the gate we simply stood and waited to be counted and transferred to the camp guard". Buca had conflicts with guards in Vorkuta writing “I was sitting, naked, on the concrete floor of the lavatory corridor in Zamarstynov Prison in Lvov, waiting for my clothes to be disinfected, when an NKVD officer came in. Without a word, he knocked me down. I doubled up to protect my groin. He went on kicking. ‘You bloody Polish fascist! It's a pity I can't watch you being executed today, but your sentence will be confirmed, you can be sure. It'll be a pleasure to watch you die.’ Then he was interrupted. My clothes, and the clothes of the others waiting with me were returned and I began to dress. But I had only got into my underpants when he began kicking me again. I held my clothes in front of me and fled down the corridor, with him behind. Suddenly I slipped on the concrete and fell, just in front of a heavy iron grille. He kicked me again, then stopped, breathless from his efforts".[30]

Joseph Scholmer[edit]

Joseph Scholmer was a doctor working for the Central Health Authority in Berlin during World War II. He studied medicine at the University of Bonn. After the end of the Second World War, Schölmerich lived in the Soviet occupation zone of Germany (SBZ) and joined the Communist Party of Germany (KPD). Scholmer was accused of being an agent of the Gestapo and of the American and British Secret Services in May 1949, In April 1949, Schölmerich was arrested by the Ministry of State Security (Soviet Union) (MGB) in East Berlin for his opposition to Stalinism and imprisoned in its central pre-trial detention centre. He spent the years from 1949 to 1953 in the Gulag camp at Vorkuta, Scholmer wrote about Vorkuta “In the three months between my arrival at Vorkuta and the beginning of November I lost more than two stone in weight. Each time we went for a bath, which was every ten days, I could see the signs of malnutrition developing rapidly. My ribs began to stick out, my legs grew thin, my arm and shoulder muscles disappeared. Severe malnutrition was staring me in the face. As a result of continually lifting heavy weights I had developed a double rupture. This seemed to offer a possible respite. I went to the surgeon during his consultation hour and asked him to operate. ‘I can't,’ he answered. ‘Ruptures can't be operated on during the winter. One prisoner in every three or four has a rupture. They're very common in the camp due to the combination of hard work and undernourishment. But everyone waits till the winter for the operation. An operation means four weeks’ rest in hospital. Now do you understand?”.

Scholmer wrote about first arriving in Vorkuta “We said very little to each other on this first day. We loaded up our sledges and pulled them over to the building site. I saw to it that the old man didn't do too much. When we said good-bye to each other he made a little bow and said: ‘Thank you very much.’ The next day I put him wise to the basic rules of camp life: (1) Do as little work as possible. (2) Eat as much as possible. (3) Get as much rest as possible. (4) Take every opportunity you can to get warm. (5) Don't stand any nonsense from anybody. (6) If anyone hits you, hit back immediately without a moment's hesitation. ‘But I've never hit a human being in my life,’ answered Moireddin. ‘If you hit anyone here you're not hitting a human being but a bit of human scum. If you once allow anyone to hit you without sticking up for yourself they'll never stop. A week later he was transferred to a brigade loading up slag. It was a filthy job for him. I saw Moireddin every day when the shifts changed. One day he wasn't there. I asked the people in his brigade what had become of him and they said: ‘Moireddin's got five days in the bur [punishment barracks]!’ ‘What for?’ ‘For hitting the brigade leader!". Scholmer wrote about the guards of vorkuta stating “Most of the soldiers at Vorkuta are simple creatures, who are really just as much prisoners of the tundra and victims of the cold as the prisoners themselves. Service up there in the north is a sort of exile for them. Their life consists of guard duties, drill and occasional visits to the cinemas in the town to which they are marched off in little columns. They put up little black targets in the snow for rifle practice. The whining of the bullets reminds the prisoners why these soldiers are being trained at all. Today they are shooting at targets, tomorrow it may be at them. People are always asking themselves how the soldiers would behave in the event of trouble. ‘Will they shoot, or will they refuse to? Will they come over to us? The government recognizes the dangers of fraternization between guards and prisoners clearly enough".

“A considerable part of my illegal medical practice in the camp consisted of trying to delay the recovery of my patients. I also had many cases in which the prisoners were being made to do such very heavy work that their only chance of survival lay in getting me to make them ill. I had the opportunity of learning a whole host of methods which prisoners use to induce or fake illness. They inject themselves under the skin with petrol. This leads to a chronic festering which stubbornly defies every form of treatment. A sore on the lower part of the leg is produced easily enough by breaking the skin and rubbing in dirt. I took over all these methods myself and perfected them. Nose bleeds are engineered easily enough by tickling the mucous membranes of the nose with a piece of wire". In mid-December 1953, Scholmer left Vorkuta with a prisoner transport train. The transport came on the 21st. January 1954 in the Fürstenwalde release camp in East Germany. Released from captivity, Schölmerich immediately fled to West Berlin, where he registered as a returnee.[31]

Alla Tumanova[edit]

Alla Tumanova was twenty years old when she was arrested in 1951, Tumanova was a student at Lenin State Pedagogical Institute, Tumanova was charged with membership in an anti-Soviet youth group. During the arrests of the anti-Soviet youth group members, Of the seventeen students who were arrested, three were executed while the rest were sent to the Gulags. Tumanova was sentenced to twenty-five years of hard labor in the Gulag, which she spent in the Abez Invalid Camp and Vorkuta Gulag. Tumanova wrote about Vorkuta "For some time our brigade worked at a coal mine face. We had to lug waste heaps from place to place, shifting the smoking rock with shovels. The work was unbearable, and not only because we were suffocating and made ill by the clouds of reddish smoke, but because no one had bothered to explain why we should move it from one place to another. It was like a kind of torture, another punishment. But later, under different circumstances, when we loaded the smoking rock onto trucks that were laying a local road, it was much easier to accept. Still, it is difficult to imagine now how we managed to survive. For five minutes, or faces covered over up to the eyes, we would toss shovelful after shovelful, almost without breathing. Then we would race several metres away, tear rags off our faces, convulsively swallow air, and then return to the scorching heat".

Tumanova wrote about her survival, "Of the entire five years of my incarceration, the most terrible months were the fifteen I spent in solitary. Time passes most slowly and oppressively in the evening. The window begins to darken and turn into a black square. The dim electric light and the brown-green walls give the small space an oppressive atmosphere. That familiar sensation of fear creeps back: if they don't call me to the interrogator during the day, then for sure it will be at night. I attempt to read, but the book cannot distract me from my heavy thoughts. Now and then I catch my eyes roaming in vain across the lines on the page, even turning the pages, but I recall nothing of what I have just read. That feeling of absurdity returns: how could I have possibly ended up here? This is an impossible accident, a delusion". “For several months one of the distractions that helped me get by was ‘correspondence by knocking’ on the wall with the neighboring cell. Unfortunately, I was ill-prepared for prison life having never learned Morse code. My neighbor, though, didn't seem to have learned it either. So she and I had to invent our own personal code. I confess this was my first genuine feeling of joy for a long time: someone on the other side of the wall wanted to be friends! I liked my invisible neighbor from the start, and from the beginning of the day was impatient for each ‘meeting.’ But our contact was brief. One day the door unexpectedly opened and a furious sergeant, the one who was senior on the floor came in. ‘Why are you knocking on the wall? Don't you know that it is forbidden in prison? The interrogator will be informed of this".

“I was surrounded by strange women – crude, unlovely faces, half-naked bodies with enormous tattoos. They spoke in shouts, interspersing their words with profanity. For awhile it seemed to me that they were speaking a foreign language; I couldn't understand half of the words. All these loudmouthed women looked old, although their figures and their wild behaviour suggested youth instead. Lida whispered to me that these were blatznyazhki, thieves, and that I should tell them nothing about myself. But they didn't need any of our help to realize that we were ‘politicals.’ They asked me about something, shouting down from the racks at the top, but I had lost the power of speech in this terrifying place. ‘Hey, pinky, you mother fucker, don't be sulky. We're not going to bite you!’ a large half-naked devakha in a bra spoke to me pleasantly from the floor. On her stomach a dark blue snake wriggled at her every movement: the tattoo had been done masterfully”. “Get out of the cell! Hands in back!’ I don't really need the orders: I do it all automatically by now, I am used to it, and in fact it makes it easier to walk. We walk along narrow metallic corridors. The endless rows of crude iron doors with inset peepholes stretch along the walls. Someone's life is rotting behind each door. A nadzorka moves unhurriedly along the soft carpet from door to the next. She wears boots, a tunic, a beret on her head, and a grey pancake instead of a face. One door after another, she goes up to the peephole and for a few seconds inspects her ward. What is she thinking during those seconds, what does she feel? The satisfaction of a job well done, probably, displaces all her other feelings. But perhaps even this is going too far. Simply put, they are paid well for working in the prisons, more than in other places. There are special rations, privileges – that is the secret of their psychology”. Tumanova's release “Two months after that evening Stalin died. Very soon after that the alleged doctor-poisoners were rehabilitated and Beria was shot, along with Abakumov and Riumin – all those who were connected with our indictment. Events piled up one after another, so quickly you couldn't get used to one before a new one came rolling along. It was truly a joyful time! We were all full of hope. Soon they started letting people go, not waiting for the end of their terms. We all waited impatiently for the changes in our lives. My mother and the parents of the others who were convicted with me were petitioning for a review of our case. Illegally convicted persons could only be released on legal grounds so we rebels had to wait longer than most. It was only on the 25th of April 1956 that all of us were released into freedom”.[32]

Günter Albrecht[edit]

Günter Albrecht was a German student sailor in the Kriegsmarine who was captured as a Prisoner of war by the British in 1944. After he was released back to Germany in Stralsund he joined the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany (LDP), the FDGB and the FDJ in 1946 in hopes of exerting liberal influence, he was arrested by the Soviets in 1949 for his liberal activities and was sent to Vorkuta in 1950. Günter wrote "At the end of 1949, I was then taken back to the investigating judge. There was another Soviet officer there. The investigating judge explained to me that this was the prosecutor. He asked many trivial questions, took notes and then explained after about two hours that I would soon have to answer to the Soviet military tribunal. I had repeatedly explained to the investigating judge that I wanted a defender. I got the same answer over and over again: 'Later.' I also demanded a defender before the so-called prosecutor. He replied that I could have that, but there is only one defender in the entire German Democratic Republic, and he does not know when this time has. It could take one, two or three years. As a result, since I finally wanted to get out of prison, I gave up in the hope of coming to a camp".[33]

Konstantin Waleryanovich Flug[edit]

Konstantin Waleryanovich Flug was a student at Baumann University of Technology, he was arrested in 1932 possibly because he wrote an essay about "terror" which came into the possession of the Joint State Political Directorate (OGPU) through a friend. Konstantin was convicted in 1933 by a remote judgment according to Articles 58–8, 10 and 11 by a special court of the OGPU to ten years of warehouse detention in an improvement labor camp. After being transported to two unknown camps in Siberia and the Ukhta Gulag Konstantin was taken to Vorkuta in 1936 where he would remain until 1946. Konstantin wrote about the first known strike in Vorkuta which was organized by Trotskyist prisoners, he wrote: "So I drove in 1939 ... to the abandoned brickworks... In the barrack walls I saw bullet holes, on the floor under the platforms there were cartridge sleeves and rags, brown spots appeared on the platforms. The clay pit was filled, not with a bulldozer, rather hastily shoveled. Body parts protruded from the earth in some places, a naked heel, an elbow. The permafrost soil rises quickly, so the contents of the mass grave could not decompose in the short polar summer. Therefore, a hand with spread fingers could protrude from the filled clay pit. I couldn't stand this sight and drove my horse to leave this place".

Horst Hennig[edit]

Horst Hennig was one of the many prisoners that participated in the Vorkuta Gulag uprising. Hennig was a student in the Martin Luther University of Halle-Wittenberg (university of Halle) studying medicine. In 1950 Hennig was arrested by the Stasi and convicted by a Soviet military tribunal in Halle to 25 years of forced labor. Hennig was transported to Vorkuta immediately after, he spent five years in Vorkuta during which he took part in the uprising of 1953 and wrote a letter and prisoner demands to the Soviet authorities that were negotiating with the prisoners in the uprising. Hennig wrote: "Our decision to stop work is motivated by the firm conviction that great injustice has been committed against us, that our human dignity has been trampled underfoot contrary to the constitutional right of the personality, that we have fallen victim to the arbitrariness of the organs of the MGB and MWD. Due to this arbitrariness, we suffered during the entire period of imprisonment and we still suffer constant mockery, terror, beating, insults and humiliation at every step of our human existence."

"So conditions have been created for us that lead to our gradual destruction. The administration installed by the popular enemy Beriya still prevents us from bringing the truth about our situation to the attention of the highest Soviet organs. We can no longer bear such a situation. All this must be ended according to the law."[34]

Albertine Hönig[edit]

Albertine Hönig was a public school teacher in Transylvania, Romania during World War II, in 1944 she started providing escape assistance to the German soldiers after Romania was occupied and joined the Soviet Union. Hönig was Arrested by the Romanian secret police in 1945 and handed over to the Soviet authorities. She was convicted of organized resistance against the Soviet Union and was sentenced to 8 years in the Gulag system. Hönig was transported to Vorkuta after and served her sentence until 1953, after her release she was exiled to Vorkuta where she would stay until 1959 when she was departed to West Germany. Hönig wrote about her experience in the camp, "A March day has begun. Outside, however, we only see a dark gray whirling and rippling, hear only howling, howling groans and rage when the "gong" sounds at four o'clock in the morning and the barracks supervisor wakes us with the hated "podjom" (get up)".

"Our Brigadier says: "The purga comes from the southwest and is hard. It won't be enough for exercising, for a day off." She's right, the required minus 36 degrees are allegedly or actually, who wants to decide, not reached. We don't want to wash until the evening," we consider, "and tie a cloth over the padded ear caps to avoid frostbite as much as possible"

"The morning soup is the purest water, the porridge burnt and inedible". "When counting at the guard, it really takes a long time. The storm lashes bits of snow and ice horizontally, making our faces wet, our eyes watering. Suddenly he is silent for seconds. In the silence, a distant, peculiar vibration can be heard, it almost sounds like the ringing of a bell. There are ventilation systems in the coal shafts. A voice behind me says in dialect-Swabian German: "The Easter bells are ringing! Today is Easter! These monsters have gotten us so far that we almost forgot." The woman in the row behind me is almost squat, with a round face in which a pair of blue eyes now flash angrily, quite toothless, although she may only be in her forties".[35]

Erwin Jöris[edit]

Erwin Jöris was a youth member of the Communist Party of Germany (KPD) who was arrested by the Gestapo in 1933 for communist activities in Fascist controlled Germany, he was sent to the Sonnenburg concentration camp (current day Brandenburg). Jöris was discharged from the concentration camp in late 1933 and on behalf of the party emigrated to Moscow, there he had a disillusionment and break with the communist worldview. Because of the break with his communist views he was arrested in 1937 by the NKVD and was sent to the Lubyanka, Jöris was sent back to Germany a year later and conscripted to the Wehrmacht in 1940, he was captured by the Red Army in 1941 and sent back to the Soviet Union as a Prisoner of war. After Jöris was sent back to East Berlin he was arrested once more and convicted by a Soviet military tribunal to 25 years of forced labor and Punishment as a political prisoner in Vorkuta, shafts 9 and 10. Jöris was released in 1955 and wrote about his time in the camp. Jöris wrote: "Initially, we worked with the so-called city brigades in the city of Vorkuta. A cold store was built there, and I had to dig a hole called Katlewan with two young German students. We were all still very weakened by the long stay in prison. The Russian prisoners received additional food through packages from home. They managed their "norm" better than we newcomers, as we had to feed on water soup for about a year. Those who did not meet the screwed-up standard got a much worse meal. In addition, we Germans were insulted by the Soviet supervisors as "fascist whores" etc.".

"After some time, I was assigned to work in the shaft. Together with my good and courageous comrade Peter Lange, I insisted on being instructed on how to work in the shaft (shaft minimum). We were successful and sat on the school desk for a week".

"After the training, I came to a brigade that dealt with the tunnelling, so it was a heavy job. Here, too, you were insulted as a "fascist pig." Surprisingly, a good relationship was created between me and the others. In the end, they realized that I was not a prisoner of war at all, as they thought, but a "fifty-eight", i.e. a political prisoner. And when I told them about my work in Moscow and the time of terror, the ice was broken. A good camaraderie was created. The work in the shaft was difficult and also very dangerous. You were often underground for 10 hours. And if the standard was not met, you got a correspondingly worse food ration. Especially we Germans didn't have it easy".

"Life in the camp was really unbearable. Many told me: "Either I'm free next year, or I'm a corpse." To cheer me up, I always said: "Next year you are not free and not dead, you just got used to this situation." And so it was then".[36]

Johannes Krikowski[edit]

Johannes Krikowski was a student living in Greifswald, in 1949 he started being openly critical of the political development in the GDR. He continued being critical of the government and the politics of East Germany and in 1951 he was arrested by the Stasi and put in a pre-trial detention in the Greifswald prison, a few days later Krikowski was handed over to the Soviet organs and transported to Schwerin. Krikowski was put in Solitary confinement, soon after he was accused of alleged espionage for the French secret service. Krikowski had a trial against several people, of whom he only knew one and was sentenced to 25 years in the Gulags, Three of the co-defendants in the trial were sentenced to death. In 1952 he was transported to Berlin and then to the Soviet Union where he would be taken to Vorkuta, Krikowski worked in the coal shaft, later (for health reasons) he was given another job. Krikowski wrote: "Whether you were sick or not, that was not further investigated. And then I finally got into this shaft VI, a lousy tunnel - maybe 60 centimeters high - where you had methane gas. I had to build stamps there with another former student. We couldn't hold this stamp because of all the powerlessness. I held the stamp, he took the hammer and immediately fell backwards from the weight of the hammer. In short, we never made the norm and accordingly always came to punishment. I knew that at 100 percent there was the full food ration. We had never reached them. ... That was the most terrible time down there in the camp. There were routes to shaft VI, they took two hours. Terrible in the Purga, the snowstorm. That is, in the morning someone always measured. If the temperatures were below forty-five degrees minus, you didn't have to stay in the shaft. But that was very, very rare. It happened once. And that was such a holiday for us not to have to go out once".[37]

Eduard Lindhammer[edit]

Eduard Lindhammer was a youth member of the Liberal Democratic Party of Germany, he was arrested in 1950 in Schwerin while in a class in high school. Lindhammer was convicted and according to Art. 58–10, para. 2 and 58–11, para. 2 StGB of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic sentenced him to 25 years in storage, he was soon after transported to Vhuta in the Soviet Union via Brest, Belarus. After being transported to Orsha and Gorky, Russia he was taken to Vorkuta and spent 4 years in the camp. Lindhammer wrote: "In my camp with about 3000 prisoners, around 35 different nations were gathered. All nations of Europe, including captured Japanese fishermen and Koreans. We ourselves had an Indian, who they had captured in Leipzig, with us and a Brazilian. In our camp, from heroes of the Soviet to the son of the President of the Supreme Soviet, sat all kinds of social strata, including the nomenklatura. The proportion of Jewish intelligence was also striking, some of which suffered particularly because many Russians were anti-Semitic".[38]

Leonid-Torwald Alwianowitsch Mjutel[edit]

Leonid Mjutel was a Red Army conscript who was released from military service for health reasons, he worked as a mechanic in the “Avantgarde” plant after being released from service. Mjutel's father, Alwian Mjutel, was arrested in 1937 and soon in the following years Mjutel's mother and his two brothers were accused of sharing an apartment and income with an enemy of the people (the father). Within a three-day period, the three were banished from Leningrad and the surrounding area. Mjutel was convicted by a special committee at the NKVD according to the so-called letter paragraph ASA (anti-Soviet agitation) he and his brothers were sentenced to five years in camp. Mjutel first worked as a logger in the Krasnoyarsk area in 1939 and then he was transported to Vorkuta in 1940. Mjutel worked on the Pechora railway between Ukhta and Koschwa, he was imprisoned in Vorkuta for a total of 8 years and wasn't released until 1946 because of the War, later he was kept in the camp "until further notice". Mjutel wrote: "The creation and destruction of traitors to the fatherland was so extensive that not all of them could be shot at once, and this task was entrusted to the Great Constructions of the Fatherland: from the Arctic Sea to the Karakum Desert, from Brest to the Kuril Islands. It should be built - not well thought out, haphazard - but by His command!! And it was built: in permafrost, covered by frozen earth and great waters. Thus He had commanded! Laid tracks, from Vorkuta east along the arctic coast. The route was built, it went ahead and behind it sank together with the tracks. But it was built, built on human bones for more than four years. ... No one was responsible for the prisoners' lives. This perverse sadism took on medieval excesses. His cradle were the interrogation rooms and torture chambers".[39]

Notable inmates[edit]

Aleksei, who was Vorkutlag's most well-known prisoner at the time was a well known screenwriter, writing the films "Lenin in October" and "Lenin in 1918." Aleksei was sent to Vorkutlag not because he was a political dissident or criminal, but because of his love affair with dictator Joeseph Stalin's daughter Svetlana, which concluded in 1943 when Kapler was sentenced to five years on fabricated charges of anti-Soviet agitation.

Mal'tsev, impressed with Kapler, allowed him to work as the city photographer and live in relatively comfortable conditions, much better than those in the rest of Vorkutlag. Kapler lived and worked outside of the camp zone, and was allowed a flat from which he could come and go as he pleased.

- Homer Harold Cox (1921–1954)

Homer Harold Cox, kidnapped in East Berlin in 1949 and released in 1953, together with US Merchant Marine Leland Towers, Americans in the Gulag.[40]

One year after his release, in 1954 Cox died of pneumonia. Shortly after his death, Cox's fiancée made a statement to the press that “murder is the only explanation” for his death, which led to rumors of a KGB plot.[17]

- Heinz Baumkötter (1912–2001) SS concentration camp doctor in Mauthausen concentration camp, arrested in 1947, released in 1956.

- Walter Ciszek (1904–1984): American Catholic priest and memoirist arrested in 1941, released in 1955 - survived.

- Shlomo Dykman (1917–1965): Jewish-Polish translator and classical scholar.

- Valentín González (1904–1983): Spanish Communist and Spanish Republican Army brigade commander during the Spanish Civil War – successfully escaped in 1949.

- Anton Kaindl (1902–1948): SS commandant of Sachsenhausen concentration camp between 1942 and 1945, died in 1948.

- Jaan Kross (1920–2007): Estonian writer.

- Jānis Mendriks (1907–1953): Latvian Catholic priest, killed in the uprising.[21][22]

- Der Nister (1884–1950): Yiddish writer.

- Eric Pleasants (1913-1998): British national who joined the Waffen-SS serving in the British Free Corps during the Second World War.

- John H. Noble (1923–2007): American survivor of the Soviet Gulag system (released after ~10 years) who wrote two books about experiences there.[41]

- Zvi Preigerzon (1900–1969): Hebrew writer and coal enrichment scientist.

- Nikolay Punin (1888–1953): Russian art scholar, curator and writer. Common law husband of poet Anna Akhmatova.

- Georgy Safarov (1891–1942): Bolshevik revolutionary, member of the Communist Party of the Soviet Union – executed.

- Günter Stempel (1908–1981): East German politician and a member of the Liberal Democratic Party.

- Edward Buca. (1926-2013): Polish Home Army soldier who was arrested in August 1945, released in 1958.[30]

- Joseph Scholmer (1913–1995): doctor working for the Central Health Authority in Berlin, Accused of being an agent of the Gestapo and the American and British Secret Services (Office of Strategic Services and MI6) in May 1949, arrested in 1949, released in 1953.[31][42]

- Vytautas Svilas (1925-1992): Lithuanian resistance leader who attempted to start Guerrilla warfare in Lithuania, arrested in June 1945, after a brutal interrogation he was sentenced to 15 years of hard labour in the Gulags and 5 years of exile. released from Vorkuta in 1956.[43]

Notable guards and staff[edit]

- Popov, Boris Ivanovich, head of state security, senior lieutenant of state security (10.05.1938-?).

- Tarkhanov, Leonid Alexandrovich, captain of state security (16.06.1938-17.03.1943).

- Mikhail Maltsev, chief and head of Vorkutlag from March 17, 1943 to 8 January, 1947.

- Kukhtikov, Alexey Demyanovich, Colonel (08.01.1947-15.04.1952).

- Dyogtev, Stepan Ivanovich, chief, colonel (15.04.1952-?); in 1955 he was mentioned as the head of Rechlag in the rank of general; at the same time, Rechlag was reorganized by joining Vorkutlag on May 28, 1954.[44][45]

- Fadeev, Alexander Nikolaevich, acting chief, colonel (01.04.1953-25.06.1953).

- Kuzma Derevyanko, Derevyanko was the chief of the Vorkuta camp from 1951 until his death in 1954.

- Prokopyev, Georgy Matveevich, Acting Chief, Lieutenant Colonel of Internal Service (29.07.1953—30.05.1954)

- Prokopyev, Georgy Matveevich, chief, colonel (31.05.1954-30.01.1959).[44]

- Titov, Pavel Yakovlevich, chief, colonel (30.01.1959-?).

Deputy chief[edit]

- Chepiga G. I., deputy chief, major, mentioned on 11.12.1946.

- Fadeev A. N., Deputy Chief, Colonel, from 17.07.1948 to 01.04.1953.

Chiefs of the special unit[edit]

- Zoya Voskresenskaya, the chief of the Special Section of Vorkuta prison-camp, who served between 1955 and 1956.

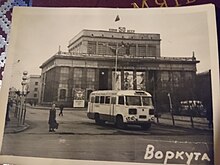

Vorkuta Gallery 1940–1968[edit]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Magidovich, Iosif Petrovich; Magidovich, Vadim Iosifovich (1985). Essay on the history of geographical discoveries. T. 4. Geographical discoveries and research of modern times (XIX - early XX centuries) (3rd ed.). p. 335.

- ^ Vekhov, N.B. (2014). Discoverer of the Urals, Science in Russia (1st ed.). p. 42.

- ^ a b "Vorkuta Tour". Vorkuta Tour. 2009.

- ^ "History of Vorkuta". History of Vorkuta (Russian: История Воркуты). 2023.

- ^ a b c "One Long Night, 1936-1938". read.aupress.ca. 2023.

- ^ The Gulag Archipelago, Volume II. 1973. p. 319. ISBN 9780061253720.

- ^ Samizdat: Voices of the Soviet Opposition, Memoirs of a Bolshevik-Leninist. PathfinderPress. 2002. p. 142. ISBN 9780873489140.

- ^ "The Pechora railway line-1937-1941". rtgcorp.ru. 2008.

- ^ "Poland WWII Kresy Deportation to USSR Gulags". KresyFamily (in Swedish). Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ S.A, Telewizja Polska. "Yet another Polish monument in Russia removed". tvpworld.com (in Polish). Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ "Various articles". ansipra.npolar.no. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ "The Gulag Study, Michael E. Allen. p.12. "Of course we have American prisoners from the Korean War here in Vorkuta"" (PDF).

- ^ Fraga, Kaleena (2022-08-11). "30 Years, 200,000 Deaths, And One Violent Uprising: Life Inside The Soviet Union's Most Brutal Gulag". All That's Interesting. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ "Vorkuta: From Labor Camps To Industrial Decline". RadioFreeEurope/RadioLiberty. Retrieved 2023-11-26.

- ^ a b c d e Barenberg, Alan (2014-08-26). Gulag Town, Company Town. Yale University Press. doi:10.12987/yale/9780300179446.001.0001. ISBN 978-0-300-17944-6.

- '^ Bacon, Edwin (January 1992). "Glasnost and the Gulag: New information on soviet forced labour around World War II". Soviet Studies. 44 (6): 1069–1086. doi:10.1080/09668139208412066. ISSN 0038-5859.

- ^ a b c d e f Barenberg, Alan (2014-08-26), "Vorkuta in Crisis", Gulag Town, Company Town, Yale University Press, pp. 120–160, doi:10.12987/yale/9780300179446.003.0005, ISBN 9780300179446, retrieved 2023-04-20

- ^ "Global Nonviolent Action Database". nvdatabase.swarthmore.edu. March 3, 2010.

- ^ "Latkovskis, Leonards. I. Baltic prisoners in the Gulag revolts of 1953". lituanus.org. September 6, 2019.

- ^ "Latkovskis, Leonards. II. Baltic prisoners of the Gulag revolts of 1953". September 6, 2019.

- ^ a b "Servant of God Fr. Janis (John) Mendriks (1907-1953)". padrimariani.org. 2023.

- ^ a b "Servant of God Fr. Janis Mendriks MIC 1907—1953". catholicmartyrs.org. April 5, 2004.

- ^ Memorial website(in Russian)

- ^ Robert Conquest, Paul Hollander: Political violence: belief, behavior, and legitimation p.55, Palgrave Macmillan;(2008) ISBN 978-0-230-60646-3

- ^ "Weather and climate in Vorkuta, Pogoda.ru.net". Pogoda.ru.net. 2004.

- ^ "ст. Сивая Маска, ул. Школьная, д. 5". October 8, 2011. Archived from the original on October 8, 2011. Retrieved March 14, 2011.

- ^ "Inside Russia's deep frozen ghost towns". www.cnn.com. 2016.

- ^ "Above the Arctic Circle, a once-flourishing Russian coal-mining town is in rapid decline". The Washington Post. December 20, 2019.

- ^ "John H. Noble-Gulag: Many Days, Many Lives". gulaghistory.org. 2008.

- ^ a b "Edward Buca "Many days, Many lives"". gulaghistory.org. 2008.

- ^ a b "Joseph Scholmer. Gulag: Many Days, Many Lives". gulaghistory.org. 2021.

- ^ "Alla Tumanova. Gulag: Many Days, Many Lives". gulaghistory.org. 2021.

- ^ "Gunter Albrecht, biography-Gulag.Memorial.de". gulag.memorial.de. 2023.

- ^ "Horst Hennig, Vorkuta prisoner". gulag.memorial.de. 2023.

- ^ "Albertine Hönig, Vorkuta prisoner". gulag.memorial.de. 2023.

- ^ "Jöris". gulag.memorial.de. Retrieved 2023-11-25.

- ^ "Krikowski". gulag.memorial.de. Retrieved 2023-10-07.

- ^ "Eduard Lindhammer, Vorkuta prisoner". gulag.memorial.de. 2023.

- ^ "Leonid-Torwald Alwianowitsch Mjutel, Vorkuta prisoner". gulag.memorial.de. 2023.

- ^ Allen, Michael E. (2023). Michael E. Allen (2005). The Gulag Study. p. 28. ISBN 9781428980020. DIANE. ISBN 9781428980020.

- ^ "An American Survivor of the Post-war Gulag". 2006. Archived from the original on November 11, 2006.

- ^ Forsbach, Ralf (2006). Ralf Forsbach: The medical faculty of the University of Bonn in the Third Reich. Oldenbourg, Munich 2006 (in German). Oldenbourg, Munich, Germany. pp. 598 f. ISBN 9783486579895.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ "He devoted his life to the freedom of the Motherland" (PDF). www3.lrs.lt. 2023.

- ^ a b "Глава VII ГУЛАГ: КАКИМ ОН БЫЛ - Воспоминания о ГУЛАГе и их авторы" (in Russian). Retrieved 2023-11-27.

- ^ "47. Июль 1955. Бунт на 4-ой шахте. Игорь Доброштан - Воспоминания о ГУЛАГе и их авторы" (in Russian). Retrieved 2023-11-27.

Further reading[edit]

- Barenberg, Alan (2014). Gulag Town, Company Town: Forced Labor and Its Legacy in Vorkuta. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-20682-1.

- Saunders, George (1974). Samizdat, Voices of the Soviet opposition. New York: Monad Press. ISBN 9780873489140.

67°30′51″N 64°05′02″E / 67.51417°N 64.08389°E