Walter Hunt (inventor)

Walter Hunt | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | July 29, 1796 Martinsburg, New York, U.S. |

| Died | June 8, 1859 (aged 62) |

| Known for | |

| Spouse | Polly Loucks (m1814) |

| Children | four |

Walter Hunt (July 29, 1796 – June 8, 1859) was an American mechanical engineer. Through the course of his work he became known for being a prolific inventor. He first became involved with mechanical innovations in a linseed producing community in New York state that had flax mills. While in New York City to promote his inventions he got involved in inventing the streetcar gong that was used throughout the United States. This then led him to invent other useful items like the safety pin and sewing machine. He invented the precursor to the repeating rifle and fountain pen. About two dozen of his inventions are used today in basically the same form as he had patented them. In spite of his many useful innovative creations he never became wealthy since he sold off most of his patent rights to others at low prices with no future royalties. Others made millions of dollars from his safety pin device.

Early life and education[edit]

Walter Hunt was born July 29, 1796, in the town of Martinsburg, in Lewis County in the state of New York. He was the first born child of Sherman Hunt and Rachel Hunt. He had twelve siblings. Hunt received his childhood education in a one-room schoolhouse. Hunt was muscular, tall and slender with a ruddy complexion.[1] He married Polly Loucks in 1814 and they had four children. Hunt went to college and earned a master's degree in masonry in 1817 at the age of 21.[2]

Mid life[edit]

Hunt traveled to New York City in 1826 to get money for one of his inventions. While there he witnessed an accident where a horse-drawn carriage ran over a child.[3] The accident event motivated him to come up with a metal bell that was operated with a hammer that could be controlled by one of driver's feet without letting go of the horse reins. Hunt patented his new innovation on July 30, 1827.[4][5] He promoted his concept to many prospects and eventually was able to sell his foot operated coach alarm mechanism idea to the stagecoach operators Kipp and Brown.[6] Hunt's innovation was soon adopted by most public horse-drawn vehicles throughout the city.[2][7][8] Hunt's coach alarm was further developed and used throughout the United States.[9]

Inventions[edit]

Hunt was a prolific inventor. From 1827 to 1830, while earning a living in the real estate field, he invented a fire engine, an improvement for hard coal-burning stoves, the first home knife sharpener,[10] and a restaurant steam table apparatus.[11] He also invented the precursor of the Winchester repeating rifle[12][13][14] and the forerunner of the American fountain pen as used in the twentieth century.[15][16][17] Additionally, Hunt invented a flax spinner, an improved oil lamp, artificial stone, the first rotary street sweeping machine,[10][18] mail sorting machinery, velocipedes, and ice plows.[19][20][21] He also made improvements to guns, cylindro-conoidal bullets,[22] ice-breaking wooden hull boats, paraffin oil candles, velocipedes, machines for making rivets and nails, and self-closing inkwells.[23][24] He also invented the Antipodean Performers suction-cup shoes claimed to be used by circus performers to ascend up solid side walls and walk upside down across high ceilings.[20][25] He did not realize the significance of many of his inventions when he produced them and sold off most of his patent rights to others for low prices making little for himself in the long run.[26] In the twentieth century many of his patented devices were widely used everyday common products.[3][27]

Sewing machine[edit]

He developed the first modern feasible operating sewing machine[20] sometime between the years 1835 and 1837[28] at his Amos Street shop that was up a narrow alley in Abingdon Square[29] at the borough of Manhattan in the city of New York.[3][30] He manufactured and sold a few of these machines at the time.[21] He never initially patented the mechanical device he created that used a lockstitch for sewing.[31] It had a characteristic of an eye-pointed needle and used two threads whereby one thread passed through a twisted loop in the other thread and then both interlocked.[32] The uniqueness of this was that it was the initial time an engineer or technician inventor had not imitated a single stitch done by hand and used two interlocking threads at a seam.[33] He used a technique for sewing which was revolutionary at the time.[31][33] The eye opening was near the point of the needle and operated on a vibrating arm and a loop was formed under the cloth by this thread through which a shuttle, reeling off another thread, was forced back and forth making an interlocked stitch.[34] Hunt completed his working model before he showed it to anyone.[35]

Hunt sold one-half the patent rights in 1834 to businessman and blacksmith George A. Arrowsmith who never manufactured it to sell.[36][37][38] He instead had Hunt's wooden version duplicated in iron by Adoniram, Hunt's brother. Adoniram was a skilled mechanic and duplicated the original wooden version. It performed better because no splinters of wood impeded the passage of the cloth.[39] Arrowsmith had no interest patenting the sewing machine then and had decided to postpone that step for a later time. He gave as reasons for not procuring a patent that 1) he was busy with other businesses then; 2) the expense of getting the appropriate drawings and paperwork together to register a patent was more than he could afford and; 3) the difficulty of introducing the new sewing machine into public use, saying it would have cost two thousand (equivalent to $61,040 in 2023) or three thousand (equivalent to $91,560 in 2023) dollars to start the sewing machine business.[34] Had he seen the newspaper article titled Sewing by Machinery of December 1835 and January 1836 that was in many nationwide newspapers he may have applied for a patent right away,[40][41] because it said that a mechanic of Rochester had invented a machine for making clothes which would thereafter take the place of fingers and thimbles.[42]

Hunt did not seek a patent for his sewing machine at the time because he worried it would create unemployment with seamstresses.[43][44] History records show that his wife and daughter advised him against marketing his sewing apparatus.[45][46][47] Hunt's daughter Caroline operated a corset-making shop with twelve seamstress ladies and was watching out for their interest and thousands of other seamstresses.[27] This ultimately led to a court case in 1854 when the lockstitch sewing machine concept was applied for by Elias Howe in a patent application.[48] Hunt submitted his initial application for his 1834 sewing machine on April 2, 1853. Records at the Supreme Court show Hunt's invention was made before Howe's machine and the Patent Office identified Hunt's preexistence but it did not issue a patent to him for this.[49] The reason was because he had not filled out the proper paperwork for a patent before Howe's paperwork application and had abandoned the design experiment of the 1830s.[50] Hunt acquired public acknowledgement for his invention, however Howe's official patent remained lawful because of the technicality of the timing of the paperwork. Isaac Singer arranged to give Hunt $50,000 (equivalent to $1,760,770 in 2023) in installments for his sewing machine design in 1858 in order to clear up the patent confusion about sewing machines, but Hunt died before Singer was able to consummate the agreement.[2][3][45]

Safety pin[edit]

Hunt thought little of the safety pin, his best-known invention. He sold his patent of it for $400 (equivalent to $14,650 in 2023) to W R Grace and Company, to pay a draftsman he owed $15 to (equivalent to $550 in 2023).[3] J.R. Chapin pressured Hunt to pay off what was due to him for the drafting work he had done on previous inventions that needed patent drawings for application submissions.[51]

Hunt came up the safety pin ("C") in 1849 through experimentation with high tension wire.[3][20][52] His invention was an improvement on the current way clothing items were attached together before because of a protective clasp ("D") at the end and a coiled wire design ("B") with a spring tension on the pointed end leg ("A") to keep it in the protective clasp even if the pin device was moved around. The basic design is the same in the twentieth century as when Hunt came up with the device in the nineteenth century and is manufactured inexpensively now.[53] W R Grace and Company made millions of dollars profit off the product.[54]

Other inventions[edit]

drawing, patent number # 14,019.

One of Hunt's popular inventions was a paper shirt collar. This time he sold the patented design and negotiated for royalty payments, but the item only became popular after he died.[3] The unusual item was first put on sale in New York City in 1854 and used then mostly for stage purposes. In time it became fashionable and the general public then started using them. High production of the item came about and at one time there were as many as forty factories making paper collars in the United States. The manufactured output in 1868 became 400,000 that were sold to the general public.[55]

tombstone 2012

Hunt often used the legal services and patent research work of Charles Grafton Page, a certified patent lawyer who had worked at the Patent Office before, when seeking a potential patent for one of his inventions.[56] His inventions covered a wide variety of fields and subjects. About two dozen of Hunt's inventions are still used in the form in which he created them over one hundred years ago.[57]

Some of Hunt's important inventions are shown below with the patent drawings.

-

Fountain pen

Patent 4927 -

Safety pin

Patent 6281 -

Nail making machine

Patent 3305 -

Sewing machine Patent #11,161 (issued June 27, 1854)

-

Swivel-Cap Stopper

Patent 9,527 -

Inkstand

Patent 4221 -

Firing cock repeating gun

Patent 6663 -

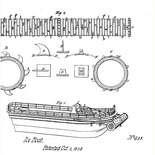

Ice Boat

Patent 958

Later life and death[edit]

Hunt created numerous usable everyday inventions in his lifetime, however he never became independently wealthy from them.[33] He died of pneumonia at his place of business in New York City on June 8, 1859.[2] He is interred in Green-Wood Cemetery at Brooklyn, New York.[58][59] His grave is marked by a small red granite shaft about a hundred feet from Howe's massive bust monument.[57][60]

Legacy[edit]

Hunt was inducted into the Inventors Hall of Fame in 2006 for the safety pin invention.[61][62] Many of Hunt's invention ideas are in actual use today and are basically the same device as when he patented them more than a hundred years ago. Some of those others besides the safety pin and sewing machine[63] are a device which regulates the amount of liquid that comes from a bottle with each tilt, a bottle stopper, springy attachment for adjustments to belts and suspenders, and a nail making machine.[60][64][65]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 1, 13.

- ^ a b c d "Walter Hunt". Encyclopedia of World Biography Online (subscription required). Gale, a Cengage Company. 2001. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g "Walter Hunt". World of Invention Online (subscription required). Gale, a Cengage Company. 2006. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ Hunt 1935, p. 3.

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 34–42.

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 43–44.

- ^ Kane 1997, p. 45.

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 45–56.

- ^ "Seeking Honor For Inventor of Sewing Machine". The Jackson Sun. Jackson, Tennessee. September 20, 1937. p. 2. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ a b Brandon 1977, p. 58.

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 57–68.

- ^ Bowman 1958, pp. 54, 55.

- ^ "Winchester / An American Legend". Chino Champion. Chino, California. June 28, 1991. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ "Sports Afield". Lake Geneva Regional News. Lake Geneva, New York. October 20, 1949. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ Kane 1997, p. 302.

- ^ Tonson 1848, p. 243.

- ^ Wilson 2017, p. 33.

- ^ Thanhauser 2022, p. 34.

- ^ Lamphier & Welch 2019, p. 284.

- ^ a b c d "Patent Laws Spur Inventiveness". The Geauga Record. Chardon, Ohio. April 9, 1955. p. 6.

- ^ a b Kaghan, Theodore (March 26, 1939). "Humanity's Hall of Fame". The Cincinnati Enquirer. Cincinnati, Ohio. p. 98 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Hellstrom 1953, pp. 13, 14.

- ^ Abbot 1944, p. 249.

- ^ Keeley 1950, p. 27.

- ^ Jimmy Stamp (2013). "The Inventive Mind of Walter Hunt, Yankee Mechanical Genius". Smithsonian arts-culture. Smithsonian. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

- ^ "Walter Hunt". Your Dictionary. 2021. Retrieved April 18, 2022.

- ^ a b Block, Jean Libman (February 22, 1952). "The Forgotten Inventor". The Sun Times. Owen Sound, Ontario, Canada. p. 4 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Byrn 1900, p. 184.

- ^ Parton 1872, p. 19.

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 69–76.

- ^ a b Cooper 1968, p. 11.

- ^ "The History of Sewing Machines !!". The Indiana Progress. Indiana, Pennsylvania. June 19, 1889. p. 13 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b c Fulton 2008, p. 846.

- ^ a b Singer Sewing Machine 1897, p. 13.

- ^ Kane 1997, p. 72.

- ^ "The Sewing Machine, Its History and Development". The Courier and Argus. Dundee, Tayside, Scotland. November 5, 1878. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "The Rise and Progress of the Sewing Machine Trade". Glasgow Herald. Glasgow, Glasgow, Scotland. April 18, 1868. p. 3 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 76–79.

- ^ Kane 1997, pp. 74.

- ^ "Sewing by Machinery". National Banner and Nashville Wig. Nashville, Tennessee. January 6, 1836. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Kane 1997, p. 79.

- ^ "Sewing by Machinery". The Weekly Mississippian. Jackson, Mississippi. January 29, 1836. Retrieved August 25, 2022.

- ^ Klooster 2009, p. 172.

- ^ Lewtin 1930, p. 559.

- ^ a b "1854 - Walter Hunt's Patent Model of a Sewing Machine". Americanhistory.si.edu. Smithsonian - National Museum of American History. Retrieved March 21, 2022.

- ^ "Do Inventions Injuren the Laborer?". The Jackson Standard. Jackson, Ohio. July 11, 1878. p. 1 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Kane 1997, p. 76.

- ^ O'Dwyer, Davin (April 29, 2011). "Inspiring innovators: Walter Hunt". Irish Times. Ireland. Retrieved October 28, 2011.

- ^ "Walter Hunt, Inventor". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. April 9, 1889. p. 23 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Keiper 1924, p. 60.

- ^ Meyer 1962, p. 267.

- ^ "The first modern safety pin". The Evening Review. East Liverpool, Ohio. April 17, 1971. p. 7 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Block, Jean Libman (September 30, 2002). "Joseph Kane, 103; Author Gug for Forgotten Facts and History". The Los Angeles Times. Los Angeles, California. p. 74 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Ayres 2021, p. 167.

- ^ "Brooklyn Man's Name submitted for Hall of Fame". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. August 1, 1920. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com

.

.  This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ Post 1976, p. 159.

- ^ a b Kane 1997, p. xi.

- ^ "Brooklyn Deadly serious / Guides lifetime love is tombs of departed". The Courier-Journal. Louisville, Kentucky. May 5, 1995. p. 2 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "'Here Lies America' is aimed at grave cultists". The Times-News. Twin Falls, Idaho. June 11, 1978. p. 68 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ a b "Today's Housewife Is Using Hunt's Everyday Inventions". Dayton Daily News. Dayton, Ohio. August 27, 1937. p. 14 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Walter Hunt / Safety Pin". Inductees - Walter Hunt/Safety Pin. National Inventors Hall of Fame. 2022. Retrieved March 22, 2022.

- ^ "National Inventors Hall of Fame Class of 2006". The Akron Beacon Journal. Akron, Ohio. May 5, 2006. p. Aoo4 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ "Brooklyn Man's Name submitted for Hall of Fame". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. Brooklyn, New York. August 1, 1920. p. 21 – via Newspapers.com

.

.

- ^ Hunt 1935, pp. 5–6.

- ^ "Walter Hunt". Smithsonian arts-culture. Smithsonian. 2021. Retrieved March 23, 2022.

Sources[edit]

- Abbot, Charles Greeley (1944). The Smithsonian series. Smithsonian Institution. OCLC 936943099.

His second patent was for a coach alarm, and through the years he received patents for a variety of things including a knife sharpener, heating stove, ice boat, nail machine, inkwell, fountain; pen, safety pin, bottle stopper, sewing machine (1854), paper collars, and a reversible metallic heel.

- Ayres, Robert U. (2021). The history and future of technology : can technology save humanity from extinction?. Cham: Marshall Cavendish Corporation. ISBN 978-3-030-71393-5. OCLC 1262192914.

- Bowman, Hank Wieand (1958). Famous guns from the Winchester Collection. Arco Company. OCLC 2481891.

- Brandon, Ruth (1977). Singer and the sewing machine : a capitalist romance. London: Barrie & Jenkins. ISBN 0-214-20156-2. OCLC 3270495.

- Byrn, Edward Wright (1900). Progress of Invention in Nineteenth Century. Munn & Company. OCLC 84303615.

Between 1832 and 1835 Walter Hunt made a lock-stitch sewing machine, but abandoned it.

- Cooper, Grace Rogers (1968). Invention of the Sewing machine. Smithsonian Institution. pp. 243 v. OCLC 453666.

Sometime between 1832 and 1834 he produced at his shop in New York a machine that made a lockstitch.

- Fulton, Robert (2008). Inventors and Inventions. Springer International Publishing. ISBN 9780761477617.

- Hellstrom, Carl R. (1953). Smith & Waeeon. Pioneer publishing company. OCLC 775873942.

- Hunt, Clinton N. (1935). Walter Hunt, American inventor. C.N. Hunt. OCLC 250585694.

Page 5 -1847, January13 - Foundation pen. The forerunner of the modern fountain pen.

- Kane, Joseph Nathan (1997). Necessity's child : the story of Walter Hunt, Americaʼs forgotten inventor (1st ed.). Jefferson, N.C.: McFarland Publishing. ISBN 978-0-7864-0279-3. OCLC 35777327.

1847, January13 - Foundation pen. The forerunner of the modern fountain pen.

- Keeley, Joseph Charles (1950). Making inventions pay. Whittlesey House. OCLC 2618845.

Hunt; obtained patents on many devices, among them the fountain pen, the breech-loading rifle, nail-making machines, and paper collars. ...

- Keiper, Frank (1924). Pioneer inventions + pioneer patents. Pioneer publishing company. OCLC 1382071.

- Klooster, John W. (2009). Icons of invention : the makers of the modern world from Gutenberg to Gates. Santa Barbara, California: Greenwood Press. ISBN 978-0-313-34744-3. OCLC 647903993.

- Lamphier, Peg A.; Welch, Rosanne (2019). Technical innovation in American history : an encyclopedia of science and technology. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO Publishing. ISBN 978-1-61069-093-5. OCLC 1054271035.

- Lewtin, Frederick Lewis (1930). Servant in the house - brief history of sewing machine. Publication ;3056. Washington DC Government Printing Office. United States National Museum / Curator, Division of Textiles. OCLC 45451578.

- Meyer, Jerome Sydney (1962). Great Inventions. Pocket Books. OCLC 655232775.

- Parton, James (1872). History of the sewing machine. The Howe machine company. OCLC 68784579.

- Post, Robert C. (1976). Physics, Patents, and Politics - Biography of Charles G. Page (1st ed.). New York: Science History Publications. ISBN 9780882020464. OCLC 2869290.

- Singer Sewing Machine (1897). Story of the Sewing Machine. Press of F. V. Strauss. OCLC 8998696.

- Thanhauser, Sofi (2022). Worn: a people's history of clothing (First ed.). New York: Doubleday Publishing. ISBN 9781524748395. OCLC 1248598617.

- Tonson, J and R (1848). The Tatler, Lucubrations of Isaac Bickerstaff, Volume 1. Buckland H. Woodfall.

Walter Hunt City of New York January 13, 1847 - for improvement in the Fountain Pen.

- Wilson, Paul C. (2017). How Inventions Really Happened. Dog Ear Publishing.

Hunt's fountain pen closely resembled the type universally used in the first half of the twentieth century.