Wang Yingkai

Wang Yingkai | |

|---|---|

王英楷 | |

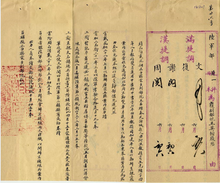

Resume of the Vice-Commander-in-Chief Wang Yingkai (覆副都統王英楷履歷) | |

| Personal details | |

| Born | 1861 Yingkou, Liaoning, Qing dynasty China |

| Died | 1908 (age 48) Beijing, Qing dynasty China |

| Alma mater | Tianjin Military Academy |

| Occupation | Military Officer |

Wang Yingkai (pinyin: Wáng Yīngkǎi; Wade–Giles: Wang Ying-k'ai; 1861–1908), whose courtesy name was Shaochen (紹宸), was a Chinese general in the Beiyang Army and first rank official of the late Qing dynasty, who served as the vice president of the Ministry of War and vice-commander-in-chief of the Plain White Banner. Wang graduated from the Tianjin Military Academy (天津武備學堂), also known as Beiyang Wubei Xuetang (北洋武備學堂), and fought with distinction in the First Sino-Japanese War. After China lost the war, he joined the Beiyang Army established by Yuan Shikai and became one of leading commanders of the army. However, during subsequent political struggles he sided with the court party against Yuan. Sun Chuanfang, who later became one of the most important warlords in the early Republican years, was his brother-in-law and protégée. Wang Yingkai died in Beijing in 1908.

Early life and career[edit]

Wang Yingkai was born into a wealthy farming family in Niuzhuang, Fengtian Province (now Yingkou, Liaoning), with his ancestral home in Shandong. Wang followed a conventional path for a young member of the gentry and participated in the imperial examination, obtaining a xiucai degree. Selected by the village as a xiāng gòng (乡贡),[1] or an intellectual chosen to work for the government, Wang served as a teacher at a private school in Haicheng but was unsuccessful in obtaining the juren degree.

In 1894, Japan sent troops to Korea and a war broke out with China. Before the year was out, the Japanese army had defeated the Chinese garrison in Pyongyang, thoroughly eliminating Chinese presence in the Korean Peninsula, and bringing the war to Chinese soil. When the Japanese laid siege to nearby Haicheng, the town elders suggested that Wang organize a local militia, which would go on to play a significant role in the five successive battles of Haicheng, which witnessed the fiercest scenes of the war.[2]

After Haicheng fell to the Japanese, Song Qing, the deputy commander of the Qing Army, and Yuan Shikai, at the time the Qing ambassador to Korea and commander of Qing troops garrisoned there, retreated to Shanhaiguan in the Zhili Province, and Wang Yingkai was instructed to bring the local militia there as well. It was at Shanhaiguan that Wang abandoned his administrative ambitions and devoted himself to becoming an army officer. Later, when Yuan Shikai became the governor of Shandong, he asked Wang to join him there, and the Wang family relocated to Jinan.

Officer of Beiyang Army[edit]

In view of the poor performance of the Huai Army during the war, the Qing government ordered the formation of a New Army competent enough to defend Chinese interests, with Yuan Shikai appointed as its first commander. In 1895, Wang joined the newly created Dingwu Army (later Beiyang Army), and rose to be one of the leading commanders in the army, serving variously as the head of the Discipline Enforcement Department, director of the First Division as well as the commander of the Second Division [3] of the Beiyang Army.

Yuan Shikai's growing power began to attract suspicion and hostility from Manchu royalty led by Yuan's former ally, court official Tie Liang (鐵良), who balked at the prospect of seeing an ambitious Han Chinese wielding power capable of toppling the ailing Qing dynasty. Mutual acrimony between Yuan and his Manchu opponents resulted in a reorganization of power and the establishment of a new Ministry of War with Tie Liang as its president. Despite being allied with Yuan since 1896, Wang Yingkai emerged from these political struggles unscathed, being elevated to become the vice president of the Ministry of War in 1907 and subsequently deputy to the Manchu General Feng Shang. That same year, an imperial edict appointed Wang Yingkai to the position of Vice-Commander-in-Chief of the Plain White Mongol Banner. In 1909, Yuan was forced to retire under the pretext of illness but would return to power in 1911.[4]

Wang also commanded half of imperial army in the autumn military exercise held before the Qing court in 1906, opposing Duan Qirui,[5] and was involved in the establishment of the Baoding Military Academy. At the time of his death, he maintained his family home in Baoding as well as an official residence at Shaojiu Hutong in Beijing.

Ranks and offices held[edit]

1902 Appointed to Second Rank

1905 Commander of First Division

1905 Advisor at Beiyang Training Bureau

1906 Brigade General, Zhili

1906 Acting Superintendent of Department of Military Administration

1906 Appointed to First Rank

1907 Vice-President of the Ministry of War

1907 Vice-Commander-in-Chief of the Plain White Banner

Death[edit]

He died in Beijing in 1908 at the age of 48 of tuberculosis.

Nickname[edit]

Owing to his obesity, he was called Fat Wang by his colleagues and subordinates alike.

Wang Yingkai and Sun Chuanfang[edit]

While in Jinan, Wang married the second eldest sister of Sun Chuanfang and provided financial support to the Sun family, which was very poor at the time. Sun was able to use natural abilities and his brother-in-law's position in the army to enroll in the newly created Baoding Military Academy. Wang also sent Sun abroad to Japan for further military study, where he graduated from the Imperial Japanese Army Academy. Upon Sun's return from Japan, Wang and his political ally, Tie Liang, happened to be the ones presiding over the examination aimed at testing fresh graduates' ability. Sun passed the tests and became an officer of the Beiyang army,[6][7] and later became a Zhili warlord and leader of the "League of Five Provinces" in the early 1920s.

Legacy[edit]

Initially, the new army formed in the Late Qing period largely modeled on its German counterpart, and therefore the instructions were all delivered in German, before the Qing government found out German designs upon Chinese territories and had the latter's military contracts terminated.[8] Knowing that the inability of Chinese officers to comprehend commands delivered by their German trainers would be a great impediment to training, he ordered the translation into vernacular Chinese of the German instructions. Phrases like 'Lizheng' (Attention) and 'Shaoxi' (Stand at ease) remain in use today.

See also[edit]

References[edit]

Citations[edit]

- ^ Wang Zhenduo, Wang Zhenduo Autobiography, http://www.doc88.com/p-8008613985704.html, Accessed July 14, 2017

- ^ Paine, S. C. The Sino-Japanese War of 1894-1895: Perceptions, power, and primacy. New York: Cambridge University Press. 2007. pg.225

- ^ Qian, J., & Han, W. (2011). Sun Chuanfang mu fu yu mu liao = Sunchuanfang mufu yu muliao. Hangzhou: Zhejiang wen yi chu ban she. pg.4

- ^ MacKinnon, S.R. (1973). The Peiyang Army, Yuan Shi-k'ai and the Origins of Modern Chinese Warlordism. Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. Vol. XXXII, No. 3. pg. 412.

- ^ Powell, R.L. (1955). Rise of the Chinese Military Power. Princeton University Press. Pg. 206.

- ^ Wang, X. (2000). Bei yang xiao jiang Sun Chuanfang = Beiyang xiaojiang Sunchuanfang. Shanghai: Shanghai ren min chu ban she. pg.23

- ^ Su, F. (2009). Sun Chuanfang. Huhehaote Shi: Nei Menggu ren min chu ban she. pg.2-3

- ^ Reynolds, D. R. (1995). China, 1895-1912 State-Sponsored Reforms and China's Late-Qing Revolution. New York: M. E. Sharpe pg.71

Sources[edit]

- Jiang, K. (1987). Republic of China Military History Volume 1. Beijing: Zhonghua shu ju.

- Qian, J., & Han, W. (2011). Sun Chuanfang mu fu yu mu liao. Hangzhou: Zhejiang wen yi chu ban she.

- Reynolds, D. R. (1995). China, 1895-1912 State-Sponsored Reforms and China's Late-Qing Revolution. New York: M. E. Sharpe

- Su, F. (2009). Sun Chuanfang. Huhehaote Shi: Nei Menggu ren min chu ban she.

- Yang, J. (1970). Haicheng Xian zhi:. Taipei: Cheng wen chu ban she.

Further reading[edit]

- Fairbank, J. K., & MacFarquhar, R. (1978). The Cambridge history of China. Late Ch'ing, 1800–1911. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.