William J. Conklin

William J. Conklin | |

|---|---|

| Born | May 2, 1923 |

| Died | November 22, 2018 Mitchellville, MD |

| Occupations | |

| Spouse | Barbara Mallon Conklin |

| Children | Chris Conklin |

| Parents |

|

William J. Conklin (May 2, 1923 – November 22, 2018) was an American architect and archaeologist.[1] In the field of architecture, he is best known as the designer of the U.S. Navy Memorial and co-designer of Reston, the planned community in Virginia. His work in archaeology focused on Incan textiles, Quipus, and textile preservation techniques used in unwrapping the Incan mummy Juanita.

Early life[edit]

William J. Conklin was born in 1923 in Hubbell, Nebraska.[2] His father J. E. Conklin[3] was a local banker and state legislator.[4] Conklin attended the Phillips Exeter Academy and, in 1944, he graduated with a degree in chemistry from Doane College, where he was the president of the student council.[5] After completing his classes, instead of attending the graduation ceremony he immediately joined the United States Navy, serving as an electronics technician in the Pacific during World War II.[6] He was stationed on a ship off the coast of Japan which recorded signals emitted from the first nuclear bombs dropped on Hiroshima and Nagasaki in 1945. In 1950 he earned a master's degree in architecture from the Harvard University Graduate School of Design.[1]

Architecture[edit]

Conklin founded the architectural firm Conklin & Rossant with James Rossant, a fellow student of Walter Gropius.[1] He later formed the firm Conklin Costantin Architects.[citation needed]

Conklin's works garnered over fifty awards in architecture and urban planning.[5] His most notable works included:

- The United States Navy Memorial in Washington, D.C. (1980–1987)[5]

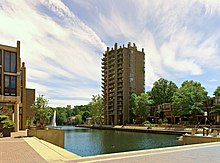

- The plan for Reston, Virginia (1964–1967), one of the leading "New Town" planned communities in the United States[7][8]

- Butterfield House in New York (1962)[9]

- Whitman Close Townhouses (1967)

- UN-sponsored master plan for Dodoma, Tanzania (1967–1972) [10]

- Brooklyn Borough Hall (renovation 1980–1989) [11]

- Myriad Botanical Gardens (1993),[12][13][14] which survived the 1995 Oklahoma City Bombing despite being located only 1,500 feet from the Murrah Federal Building[5]

Conklin served as president of the New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects[5] and vice chair of the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission.[15]

While an advocate of historic preservation, he also advocated for modern updates such as painting New York's Ward's Island Bridge in bright colors.[16]

Archaeology[edit]

After a trip to Machu Picchu in Peru, Conklin became fascinated with Incan textiles.[10] In particular, he studied how the Incas recorded information using Quipus - knotted strings used for record keeping. While it was previously understood that Quipus used three types of knots to represent a decimal system, Conklin observed to his friend Gary Urton that the knots were also tied facing forward or backward - storing additional information. This led to the realization that fibers which had been dyed with a red or blue tint may also have been part of the record keeping system. [17] Conklin's work preserving Incan textiles was demonstrated in the process of unwrapping the Incan mummy Juanita, which was documented in an episode of the PBS series Nova, Ice Mummies: Frozen In Heaven.[18]

He credited his long-time interest in historic textiles to his Nebraska grandmothers' tradition of quilt making; to the wife of a Doane professor who taught him to weave; and to his acquaintance with Junius Bird of the American Museum of Natural History in New York.[10][5]

Conklin wrote approximately 50 papers or books on ancient Andean textiles. In addition to Incan Quipus, he authored papers on some of the most ancient textiles found in the Americas 5,000 years ago.[5]

He was as a research associate at the Institute of Andean Studies in Berkeley and at the Textile Museum in Washington D.C.[citation needed]

Religion[edit]

Conklin formed ARC (Arts, Religion, and Contemporary Culture) in New York along with the mythologist Joseph Campbell, avant-garde artists Robert Motherwell and Ad Reinhardt, MOMA curator Alfred Barr Jr., literary critics Stanley Hoper and Amos Wilder, and psychiatrist Rollo May. The group was active for a quarter century, organizing a variety of talks and publications.[19]

Personal life[edit]

Conklin met Barbara Mallon at Doane College. In his junior year he led the senior graduation parade with Barbara.[5] After moving to New York, Barbara became the curator of the American Museum of Natural History. They had one son, Chris.

He had one sister, Ruth Conklin, who was married to the US Congressman and District Court Judge Robert V. Denney.

William and Barbara lived in New York for most of their lives. They later moved to Washington D.C. and bought a condo in the building overlooking the circular US Navy Memorial and the National Archive on the other side of Pennsylvania Avenue.

After the election of 2008, Conklin sent a letter to President-elect Barack Obama on November 22, 2008, with an idea for Obama's inauguration. He suggested that in the inaugural parade up Pennsylvania Avenue, Obama could emerge from his limo at the point between the Navy Memorial and the National Archive. “This momentary action on your part could express your admiration of (and support for) the Founding American Documents, and also perhaps show your appreciation of the military,” Conklin wrote. “Then you would return to your car and be on your way to the White House.” In the post-inauguration parade, despite elevated security concerns which called for a new highly armored limo, President Obama and the First Lady essentially followed Conklin's idea and walked a couple blocks in the frigid weather. The Conklins watched from their balcony over the Navy Memorial while hosting 16 journalism students and a professor from their alma mater Doane College.[20]

Selected publications[edit]

- William J. Conklin, "The Information System of Middle Horizon Quipus", The New York Academy of Science, May 1982

- William J. Conklin, "Notes on the Butterfield House", New York Chapter of the American Institute of Architects, 2005

- Conklin, W. J., Quilter, J., Chavín: Art, Architecture, and Culture, 2008, ISBN 978-1931745468

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ a b c "William J. Conklin, architect who designed Navy Memorial, parts of Reston, dies at 95". Washington Post. 15 December 2018. Retrieved 2019-03-10.

- ^ " POPULATION OF NEBRASKA INCORPORATED PLACES, 1860 to 1920, Nebraska.gov

- ^ " J E Conklin, Find A Grave

- ^ [1], Legislative Journal of the State of Nebraska, 49th (Extraordinary) Session

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Doane Commencement Spans May 14-16"

- ^ "Conklins cherish education, even after 65 years", Doane Line, February 12, 2009

- ^ "Guide to the Conklin and Rossant Reston project collection, 1960-1990", George Mason University Libraries

- ^ Robert E. Simon Jr. "Reston's Unsung Hero", Washington Post, April 4, 2014

- ^ "New Kid on the Block", Off The Grid, September 15, 2011

- ^ a b c "American Architecture Now: William Conklin", Diamonstein-Spielvogel Video Archive, 1982

- ^ "Three New York City Success Stories", New York Times, July 22, 1990

- ^ "Jubilant whoops greet botanical tube's hoops", NEWSOK, October 31, 1983

- ^ "Oklahoma’s 21st Century Park: Myriad Botanical Gardens", Texas Society of Architects, January 9, 2014

- ^ "Greening the City", Architect Magazine, September 20, 2012

- ^ Ben Baccash "Oral Histories: Charles A. Platt", The New York Preservation Archive Project, February 9, 2012

- ^ E. J. Kahn, "Bright Bridge" The New Yorker, December 20, 1976

- ^ Gareth Cook "Untangling the Mystery of the Inca", Wired, January 1, 2007

- ^ "Ice Mummies: Frozen In Heaven", Nova, November 24, 1998

- ^ John Dillenberger "The Visual Arts and Christianity in America", September 13, 2004

- ^ "Why the President “Stepped Out” During His Inaugural Parade", Huffington Post, May 03, 2009