Antigua and Barbuda

Antigua and Barbuda | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Each Endeavouring, All Achieving" | |

| Anthem: "Fair Antigua, We Salute Thee" | |

| |

| Capital and largest city | St. John's 17°7′N 61°51′W / 17.117°N 61.850°W |

| Vernacular language | Antiguan and Barbudan Creole |

| Working language | English[2] |

| Ethnic groups (2020[3]) |

|

| Religion (2020[4]) |

|

| Demonym(s) | Antiguan and Barbudan |

| Government | Unitary parliamentary constitutional monarchy |

• Monarch | Charles III |

| Sir Rodney Williams | |

| Gaston Browne | |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| Senate | |

| House of Representatives | |

| Formation | |

• Barbuda (Extension of Laws of Antigua) Act | 23 September 1859[5] |

• Annexation of Redonda | 26 March 1872 |

• Parish Boundaries Act | 17 December 1873[6] |

| 27 February 1967 | |

• Independence | 1 November 1981 |

| Area | |

• Total | 440 km2 (170 sq mi) (182nd) |

• Water (%) | negligible |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• 2011 census | |

• Density | 186/km2 (481.7/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2023 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| HDI (2022) | very high (54th) |

| Currency | East Caribbean dollar (XCD) |

| Time zone | UTC-4 (AST) |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +1-268 |

| ISO 3166 code | AG |

| Internet TLD | .ag |

Website ab | |

Antigua and Barbuda (UK: /ænˈtiːɡə ... bɑːrˈbuːdə/, US: /ænˈtiːɡwə ... bɑːrˈbjuːdə/) is a sovereign island country in the Caribbean. It lies at the conjuncture of the Caribbean Sea and the Atlantic Ocean in the Leeward Islands part of the Lesser Antilles.

The country consists of two major islands, Antigua and Barbuda, which are approximately 40 km (25 mi) apart, and several smaller islands, including Great Bird, Green, Guiana, Long, Maiden, Prickly Pear, York, and Redonda. The permanent population is approximately 97,120 (2019[update] estimates), with 97% residing in Antigua.[13] St. John's, Antigua, is the country's capital, major city, and largest port. Codrington is Barbuda's largest town.

In 1493, Christopher Columbus surveyed the island of Antigua, which he named for the Church of Santa María La Antigua.[14] Great Britain colonized Antigua in 1632 and Barbuda in 1678.[14] A part of the Federal Colony of the Leeward Islands from 1871, Antigua and Barbuda joined the West Indies Federation in 1958.[15] With the breakup of the federation in 1962, it became one of the West Indies Associated States in 1967.[16] Following a period of internal self-governance, it gained full independence from the United Kingdom on 1 November 1981. Antigua and Barbuda is a member of the Commonwealth and a Commonwealth realm; it is a constitutional monarchy with Charles III as its head of state.[17]

The economy of Antigua and Barbuda is largely dependent on tourism, which accounts for 80% of its GDP. Like other island nations, Antigua and Barbuda is vulnerable to the effects of climate change, such as sea level rise, and increased intensity of extreme weather like hurricanes. These cause coastal erosion, water scarcity, and other challenges.[18]

Antigua and Barbuda offers a citizenship by investment program.[19] The country levies no personal income tax.[20]

Etymology

[edit]Antigua is Spanish for 'ancient' and barbuda is Spanish for 'bearded'.[13] The island of Antigua was originally called Wadadli by the Arawaks and is locally known by that name today; the Caribs possibly called Barbuda Wa'omoni. Christopher Columbus, while sailing by in 1493, may have named it Santa Maria la Antigua, after an icon in the Spanish Seville Cathedral. The "bearded" of Barbuda is thought to refer either to the male inhabitants of the island, or the bearded fig trees present there.[21]

History

[edit]Pre-colonial period

[edit]Antigua was first settled by archaic age hunter-gatherer Native Americans called the Ciboney.[13][22][23] Carbon dating has established the earliest settlements started around 3100 BC.[24] They were succeeded by the ceramic age pre-Columbian Arawak-speaking Saladoid people who migrated from the lower Orinoco River.[25] They introduced agriculture, raising, among other crops, the famous Antigua Black Pineapple (Ananas comosus), corn, sweet potatoes, chiles, guava, tobacco, and cotton.[26] Later on the more bellicose Caribs also settled the island, possibly by force.

European arrival and slavery

[edit]Christopher Columbus was the first European to sight the islands in 1493.[22][23] The Spanish did not colonise Antigua until after a combination of European and African diseases, malnutrition, and slavery eventually extirpated most of the native population; smallpox was probably the greatest killer.[27]

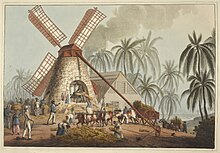

The English settled on Antigua in 1632;[23][22] Christopher Codrington settled on Barbuda in 1685.[23][22] Tobacco and then sugar was grown, worked by a large population of slaves transported from West Africa, who soon came to vastly outnumber the European settlers.[22]

Colonial era

[edit]The English maintained control of the islands, repulsing an attempted French attack in 1666.[22] The brutal conditions endured by the slaves led to revolts in 1701 and 1729 and a planned revolt in 1736, the last led by Prince Klaas, though it was discovered before it began and the ringleaders were executed.[28] Slavery was abolished in the British Empire in 1833, affecting the economy.[23][22] This was exacerbated by natural disasters such as the 1843 earthquake and the 1847 hurricane.[22] Mining occurred on the isle of Redonda, however, this ceased in 1929 and the island has since remained uninhabited.[29]

Part of the Leeward Islands colony, Antigua and Barbuda became part of the short-lived West Indies Federation from 1958 to 1962.[23][22] Antigua and Barbuda subsequently became an associated state of the United Kingdom with full internal autonomy on 27 February 1967.[22] The 1970s were dominated by discussions as to the islands' future and the rivalry between Vere Bird of the Antigua and Barbuda Labour Party (ABLP) (Premier from 1967 to 1971 and 1976 to 1981) and the Progressive Labour Movement (PLM) of George Walter (Premier 1971–1976). Eventually, Antigua and Barbuda gained full independence on 1 November 1981; Vere Bird became prime minister of the new country.[22] The country opted to remain within the Commonwealth, retaining Queen Elizabeth as head of state, with the first governor, Sir Wilfred Jacobs, as governor-general. Succeeding Sir Wilfred Jacobs were Sir James Carlisle (June 10, 1993 – June 30, 2007), Dame Louise Lake-Tack (July 17, 2007 – August 14, 2014.), and the present governor, Sir Rodney Williams: (August 14, 2014 – present).

Independence era

[edit]The first two decades of Antigua's independence were dominated politically by the Bird family and the ABLP, with Vere Bird ruling from 1981 to 1994, followed by his son Lester Bird from 1994 to 2004.[22] Though providing a degree of political stability, and boosting tourism to the country, the Bird governments were frequently accused of corruption, cronyism and financial malfeasance.[23][22] Vere Bird Jr., the elder son, was forced to leave the cabinet in 1990 following a scandal in which he was accused of smuggling Israeli weapons to Colombian drug-traffickers.[30][31][23] Another son, Ivor Bird, was convicted of selling cocaine in 1995.[32][33]

In 1995, Hurricane Luis caused severe damage on Barbuda.[34]

The ABLP's dominance of Antiguan politics ended with the 2004 Antiguan general election, which was won by Winston Baldwin Spencer's United Progressive Party (UPP).[22] Winston Baldwin Spencer was Prime Minister of Antigua and Barbuda from 2004 to 2014.[35] However the UPP lost the 2014 Antiguan general election, with the ABLP returning to power under Gaston Browne.[36] ABLP won 15 of the 17 seats in the 2018 snap election under the leadership of incumbent Prime Minister Gaston Browne.[37]

In 2016, Nelson's Dockyard was designated as a UNESCO World Heritage Site.[38]

Most of Barbuda was devastated in early September 2017 by Hurricane Irma, which brought winds with speeds reaching 295 km/h (185 mph). The storm damaged or destroyed 95% of the island's buildings and infrastructure, leaving Barbuda "barely habitable" according to Prime Minister Gaston Browne. Nearly everyone on the island was evacuated to Antigua.[39] Amidst the following rebuilding efforts on Barbuda that were estimated to cost at least $100 million,[40] the government announced plans to revoke a century-old law of communal land ownership by allowing residents to buy land; a move that has been criticised as promoting "disaster capitalism".[41]

Geography

[edit]Limestone formations, rather than volcanic activity, have had the most impact on the topography of both Antigua and Barbuda, which are both relatively low-lying islands. Boggy Peak, also known as Mt. Obama from 2008 to 2016, is the highest point on both Antigua and Barbuda. It is the remnant of a volcanic crater and rises a total of 402 meters. Boggy Peak is located in the southwest of Antigua (1,319 feet).[13][22]

Both of these islands have very irregularly shaped coastlines that are dotted with beaches, lagoons, and natural harbors. There are reefs and shoals that surround the islands on all sides. Because of the low amount of rainfall, there are not many streams. On neither of these islands can sufficient quantities of fresh groundwater be found.[13]

Redonda is a small, uninhabited island located about 40 kilometers (25 miles) to the south-west of Antigua. Redonda is a rocky island.[22]

Cities and villages

[edit]The most populous cities in Antigua and Barbuda are mostly on Antigua, being Saint John's, All Saints, Piggotts, and Liberta.[42] The most populous city on Barbuda is Codrington. It is estimated that 25% of the population lives in an urban area, which is much lower than the international average of 55%.[43][44]

Islands

[edit]Antigua and Barbuda consists mostly of its two namesake islands, Antigua, and Barbuda. Other than that, Antigua and Barbuda's biggest islands are Guiana Island and Long Island off the coast of Antigua, and Redonda island, which is far from both of the main islands.

Climate

[edit]Rainfall averages 990 mm (39 in) per year, with the amount varying widely from season to season. In general the wettest period is between September and November. The islands generally experience low humidity and recurrent droughts. Temperatures average 27 °C (80.6 °F), with a range from 23 °C (73.4 °F) to 29 °C (84.2 °F) in the winter to from 25 °C (77.0 °F) to 30 °C (86.0 °F) in the summer and autumn. The coolest period is between December and February.

Hurricanes strike on an average of once a year, including the powerful Category 5 Hurricane Irma, on 6 September 2017, which damaged 95% of the structures on Barbuda.[45] Some 1,800 people were evacuated to Antigua.[46]

Officials quoted by Time indicated that over $100 million would be required to rebuild homes and infrastructure. Philmore Mullin, Director of Barbuda's National Office of Disaster Services, said that "all critical infrastructure and utilities are non-existent – food supply, medicine, shelter, electricity, water, communications, waste management". He summarised the situation as follows: "Public utilities need to be rebuilt in their entirety... It is optimistic to think anything can be rebuilt in six months ... In my 25 years in disaster management, I have never seen something like this."[47]

Environmental issues

[edit]Like other island nations, Antigua and Barbuda faces unique environmental issues created by its proximity to the ocean, and small size. These include pressures on drinking water resources, natural ecosystems, and deforestation more generally.

Existing issues on the island are further made worse by climate change, where, not unlike other island nations affected by climate change, sea level rise and increased weather variability, create increased pressures on the communities on the islands and the land, through processes like coastal erosion and saltwater intrusion.[48]

Not only do these issues threaten the residents of the island, but also interfere with the economy – where tourism is 80% of the GDP.[49] The 2017 hurricane season was particularly destructive, with Hurricane Maria and Hurricane Irma, repeatedly damaging vulnerable infrastructure on the islands of Antigua and Barbuda.[50]Demographics

[edit]

Ethnic groups

[edit]Antigua has a population of 93,219,[51][52] mostly made up of people of West African, British, and Portuguese descent. The ethnic distribution consists of 91% Black, 4.4% mixed race, 1.7% White, and 2.9% other (primarily East Indian). Most Whites are of British descent. Christian Levantine Arabs and a small number of East Asians and Sephardic Jews make up the remainder of the population.

An increasingly large percentage of the population lives abroad, most notably in the United Kingdom (Antiguan Britons), the United States and Canada. A minority of Antiguan residents are immigrants from other countries, particularly from Dominica, Guyana and Jamaica, and, increasingly, from the Dominican Republic, St. Vincent and the Grenadines and Nigeria. An estimated 4,500 American citizens also make their home in Antigua and Barbuda, making their numbers one of the largest American populations in the English-speaking Eastern Caribbean.[53] 68.47% of the population was born in Antigua and Barbuda.[54]

Languages

[edit]The language most commonly used in business is English. There is a noticeable distinction between the Antiguan accent and the Barbudan one.

When compared to Antiguan Creole, Standard English was the language of choice in the years leading up to Antigua and Barbuda's attainment of their independence. The Antiguan Creole language is looked down upon by the upper and middle classes in general. The Antiguan Creole language is discouraged from use in the educational system, and instruction is carried out in Standard (British) English instead.

A significant number of the words that are used in the Antiguan dialect are derived from both the British and African languages. This is readily apparent in phrases such as "Innit?" which literally translates to "Isn't it?" Many common island proverbs can be traced back to Africa, such as the pidgin language.

Approximately 10,000 people are able to speak in Spanish.[55]

Education

[edit]Education in Antigua and Barbuda is compulsory and free for children between the ages of 5 and 16 years.[56] The system is modeled on the British educational system. The current Minister of Education, Sport & Creative Industries is Daryll Sylvester Matthew.[57]

The adult literacy rate in Antigua and Barbuda is approximately 99%.[58][59]

Religion

[edit]-

St. John's Cathedral, St. John's

-

Baxter Memorial Methodist Church, St.Paul Parish

A majority (77%)[13] of Antiguans are Christians, with the Anglicans (17.6%) being the largest single denomination. Other Christian denominations present are Seventh-day Adventist Church (12.4%), Pentecostalism (12.2%), Moravian Church (8.3%), Roman Catholics (8.2%), Methodist Church (5.6%), Wesleyan Holiness Church (4.5%), Church of God (4.1%), Baptists (3.6%),[60] Mormonism (<1.0%), as well as Jehovah's Witnesses.

Government and politics

[edit]Government

[edit]

Antigua and Barbuda is a unitary[61] parliamentary democracy under a constitutional monarchy.[62] The current Constitution of Antigua and Barbuda was adopted upon independence on 1 November 1981.[63] This replaced the pre-independence constitution of the Associated State of Antigua, which did not thoroughly define the relationship between the two islands.[64] The island of Barbuda maintains much autonomy, while the island of Antigua is directly governed by the national government.[63]

The executive branch has two primary leaders. The Governor-General, currently Rodney Williams, exercises the functions of the Monarch of Antigua and Barbuda, in whom executive power is vested in. The Governor-General serves at the pleasure of the Monarch,[63] and usually serves a similar term to that of the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister, currently Gaston Browne, is the head of government, and is appointed by the Governor-General. The Prime Minister must be a member of the House of Representatives, and must be the member of the House of Representatives who is most likely to command the support of the majority of members. The Governor-General has the ability to dissolve Parliament on the advice of the Prime Minister, or when the majority of the members of the House of Representatives pass a motion of no confidence, and the Prime Minister does not within seven days resign or advise the Governor-General to dissolve Parliament.[63]

The legislative power of Antigua and Barbuda is vested in Parliament, which is composed of the Monarch, the Senate, and the House of Representatives. The Senate is composed of seventeen members, who are appointed by the Governor-General. Ten of the members are appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister, these members being known as government senators. An eleventh government senator is also appointed on the advice of the Prime Minister, who must be an inhabitant of Barbuda. Four of the members are appointed on the advice of the Leader of the Opposition, these senators being known as opposition senators. One of the members is appointed on the advice of the Barbuda Council, and an independent senator is appointed under the discretion of the Governor-General himself. The House of Representatives is currently composed of seventeen elected members, as well as the Speaker of the House, who is elected by the members of the House itself. The Attorney General, while currently an elected member of Parliament, Steadroy Benjamin, may also be appointed to the House of Representatives as an ex officio member. The Attorney-General also attends sittings of the Senate. Any bill except money bills may be introduced in either chamber: money bills may only be introduced in the House. Parliament may not amend the Barbuda Local Government Act without the consent of the Barbuda Council.[63]

The judiciary of Antigua and Barbuda is composed of the magistrates' courts, the Supreme Court including the High Court and the Court of Appeal, and finally the Judicial Committee of the Privy Council, the country's final court.[65] Antiguan and Barbudan voters rejected a proposal to make the Caribbean Court of Justice the final court in 2018.[66] Antigua and Barbuda is composed of three magistrates' courts districts,[67] and is part of the Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court system.[68] The acting chief justice of the Supreme Court is Mario Michel, serving since 5 May 2024.

Since the 1990s, the two major parties in Antigua have been the centre-right (formerly left-wing) Antigua and Barbuda Labour Party, and the left-wing social democratic United Progressive Party. The Labour Party and its predecessors have traditionally been the dominant party on the national level since the 1946 general elections, with brief pauses during the Progressive Labour Movement government (predecessor of the UPP) from 1971 to 1976, and the United Progressive Party government from 2004 until 2014.[69] On Barbuda, dominant party is traditionally the Barbuda People's Movement, being the only political grouping in the Barbuda Council since 2023.[70][69]

Administrative divisions

[edit]

Antigua and Barbuda is composed of six parishes and two dependencies. Saint John is the most populous parish, home to well over half of Antigua and Barbuda's population.[71] During colonial times, the parishes were governed by parish vestries, however, the parishes now lack any sort of government.[72] Since the 2023 general elections, various proposals have been made to establish parish councils, however, as of June 2024, none have been established.[73][74] The dependency of Redonda is part of the parish of Saint John under the Redonda Annexation Act, in Magistrates' District "A".[75]

|

|

Local government in Antigua and Barbuda is completely inactive, except for the Barbuda Council which is enshrined in the Constitution.[76] Antigua historically had a system of village councils in the 1940s (although the legislation was never repealed), however, the Gaston Browne administration has expressed opposition to all forms of local governance.[77][78] St. John's also historically had a city council during the late 1800s and early 1900s,[79][80] however the St. John's Development Corporation has since consumed most of its functions.[81]

Foreign relations

[edit]

The Minister of Foreign Affairs, Agriculture, Trade & Barbuda Affairs is responsible for overseeing the foreign relations of Antigua and Barbuda.[82] The current minister is Paul Chet Greene.[83] Antigua and Barbuda is a founding member of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States,[84] as well as a member of the United Nations,[85] the Caribbean Community,[86] the Alliance of Small Island States,[87] and the World Trade Organization.[88]

Antigua and Barbuda's foreign policy has been described by Gaston Browne as a system of "we are friends of all; enemies of none". Antigua and Barbuda has also rejected the notion that it is in any country's "backyard".[89][90] Antigua and Barbuda usually maintains close relations with other Small Island Developing States, and has hosted various summits on that subject.[91] The United Nations has also praised Antigua and Barbuda for its "United Nations-based multilateralism" efforts.[92] Antigua and Barbuda also has close relations with many Caribbean countries and territories, especially Montserrat,[93] which Antigua and Barbuda accepted 3,000 refugees from in 1997 after the Soufrière Hills eruption.[94] Many policies adopted by the Antiguan and Barbudan government have also often had an impact on Montserrat, due to Antigua and Barbuda hosting the only air and transportation links into the territory.[95]

Defence and national security

[edit]

The Minister of Finance, Corporate Governance & Public Private Partnerships is responsible for the Antigua and Barbuda Defence Force, the country's military.[96] The Minister of Legal Affairs, Public Safety, Immigration and Labour is responsible for the national security of Antigua and Barbuda.[97] The Defence Force consists of the Regiment (army), the Air Wing, the Coast Guard, and the Service and Support Battalion. The Defence Force is led by the Chief of Defence Staff, who is subject to the orders of the Governor-General.[98] The Defence Force is headquartered at Camp Blizzard.

The National Security Council is responsible for the coordination of Antigua and Barbuda's national security. The National Security Adviser is a member of the council and is responsible for the gathering of intelligence and information on national security matters.[99]

The Royal Police Force of Antigua and Barbuda is the national police force of Antigua and Barbuda.[100] The Special Service Unit is Antigua and Barbuda's police tactical unit.[101] The Police Force is composed of four lettered regional divisions, and subordinated service districts.[102]

Human rights

[edit]As of July 2022, Same-sex sexual activity is legal in Antigua and Barbuda.[103][104]

Economy

[edit]Tourism dominates the economy, accounting for more than half of the gross domestic product (GDP).[13][22] As a destination for the most affluent travelers, Antigua is well known for its extensive collection of five-star resorts. However, weaker tourist activity in lower and middle market segments since the beginning of the year 2000 has slowed the economy and put the government into a tight fiscal corner.[13] Antigua and Barbuda has enacted policies to attract high-net-worth citizens and residents, such as enacting a 0% personal income tax rate in 2019.[20]

The provision of investment banking and financial services also constitutes a significant portion of the economy. Major international financial institutions such as the Royal Bank of Canada (RBC) and Scotiabank both maintain offices in Antigua. PriceWaterhouseCoopers, Pannell Kerr Forster, and KPMG are some of the other companies in the financial services industry that have offices in Antigua.[105] The United States Securities and Exchange Commission has leveled allegations against the Antigua-based Stanford International Bank, which is owned by the Texas billionaire Allen Stanford, of orchestrating a massive fraud that may have resulted in the theft of approximately $8 billion from investors.[106]

The nation, which consists of two islands, directs the majority of its agricultural production toward the markets that are found within the nation. This is done despite the fact that the nation has a limited water supply and a shortage of laborers as a result of the higher wages offered in the tourism and construction industries.[60]

Manufacturing comprises 2% of GDP and is made up of enclave-type assembly for export, the major products being bedding, handicrafts, and electronic components.[107] Prospects for economic growth in the medium term will continue to depend on income growth in the industrialised world, especially in the United States,[60] from which about one-third to one-half of all tourists come.[108]

Access to biocapacity is lower than world average. In 2016, Antigua and Barbuda had 0.8 global hectares[109] of biocapacity per person within its territory, much less than the world average of 1.6 global hectares per person.[110] In 2016, Antigua and Barbuda used 4.3 global hectares of biocapacity per person – their ecological footprint of consumption. This means they use more biocapacity than Antigua and Barbuda contains. As a result, Antigua and Barbuda are running a biocapacity deficit.[109]

The Citizenship by Investment Unit (CIU) is the government authority responsible for processing all applications for Agent's Licenses as well as all applications for Citizenship by Investment made by applicants and their family members. This unit was established by the Prime Minister and is known as the Citizenship by Investment Unit.[111]

Culture

[edit]

The music of Antigua and Barbuda has a primarily African character, with minimal influence from European music.[112] The first known records of music in Antigua and Barbuda dates back to Christopher Columbus' discovery of the island nation in 1493, when it was still home to Arawak and Carib people. Still, very little research has been done on early music from the islands. African labourers are documented in history to have danced outside in the 1780s to the toombah (later tum tum), a drum adorned with tin and shell jingles, and the banjar (later bangoe, maybe related to the banjo).[113] Antigua's indigenous music, known as Benna, came into being after slavery was abolished. Benna uses a call-and-response format, and its audience is typically interested in obscene gossip and rumours. Benna was widely utilised as a popular communication tool by the beginning of the 20th century, disseminating information around the island.[113][114]

The art of Antigua and Barbuda began with the Arawak people. Their artwork included pictographs and petroglyphs. These geometric shapes, animals, and plant artworks are said to have been used for ceremonial or religious purposes. Painting, sculpture, and ceramics were among the artistic traditions that European settlers brought to Antigua and Barbuda. Local painters used European art forms to produce Antiguan and Barbudan art in their own unique styles. Social issues, nature, and Caribbean identity were the subjects of this artwork.[115] Traditional crafts from Antigua and Barbuda include scrimshaw, pottery, sculptures, ethnic dolls, and photography.[116]

Every year, on the island of Antigua, people celebrate their freedom from slavery with the Antigua Carnival. Over thirteen days, there are brightly coloured costumes, talent events, beauty pageants and music. The celebration runs from late July to Carnival Tuesday, the first Tuesday in August. On the island, Carnival Tuesday and Monday are both observed as public holidays. In an effort to boost travel to Antigua and Barbuda, the Old Time Christmas Festival was replaced in 1957 by the Antiguan Carnival.[117][118][119] Another annual festival held in Antigua is Antigua Sailing Week. Sailing Week is a week-long yacht regatta held in the waters of English Harbour. Sailing Week was founded in 1967 and is known for being one of the top regattas in the world.[120][121] The main festival held in Barbuda is Caribana. Caribana takes place every year during Whit Monday weekend[122] and features various pageants, calypso competitions, and weekend beach parties.[123]

Antigua and Barbuda has eleven public holidays.[122] On the advice of the Cabinet, the Governor-General may also proclaim other holidays.[124] Historically, about three weeks before Christmas Day, carol singers would roam the various villages, carrying carol trees and lanterns. "John Bulls" are replicas of "masked African witch doctors", that often dominated the country's Christmas festivities. Jazz bands were also common sights, dressed in red and green clown costumes.[125]

Cuisine

[edit]Fungee (pronounced "foon-jee") and pepperpot are the national dishes. Fungee is a cornmeal-based dish that resembles Italian polenta.[126] Other regional cuisines include saltfish, lobster (from Barbuda), ducana, and seasoned rice. Additionally, there are regional confections such peanut brittle, sugar cake, fudge, and raspberry and tamarind stew. The Antigua black pineapple is prized for its juicy, sweet flesh, which is claimed to taste different from other pineapple kinds. It is a well-liked fruit in the area and is included into many regional specialties and sweets. It is said to be the sweetest variety of pineapple.[127][128]

An important part of the Antiguan and Barbudan breakfast is Antigua Sunday bread. It is sold in many bakeries on both islands, and instead of being made with butter, it is made with lard. There are often decorative twists on the crust of the bread.[129][130] Antiguan raisin buns, often called "bun and cheese", is another traditional bread, which is sweet and most popular during Easter. It is sometimes made with spices such as nutmeg.[131]

Sport

[edit]

Cricket is the most popular sport within the islands. With Sir Isaac Vivian Alexander Richards KNH OBE OOC who represented the West Indies cricket team between 1974 and 1991, Antigua had one of the world's most famous batsmen ever.[132][133] The Antigua and Barbuda national cricket team represented the country at the 1998 Commonwealth Games, but Antiguan cricketers otherwise play for the Leeward Islands cricket team in domestic matches and the West Indies cricket team internationally. Teams from the various villages and parishes compete in the Parish League.[134]

Association football is the second most popular sport in the country,[135] with the Antigua and Barbuda national football team being founded in 1928.[136]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ The World Factbook, Central Intelligence Agency, 2012, p. 32, ISBN 9780160911422

- ^ "Government of Antigua and Barbuda". Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "ECLAC/CELADE Redatam+SP 03/21/2022" (PDF). redatam.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 March 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "National Profiles".

- ^ "CHAPTER 43 : THE BARBUDA (EXTENSION OF LAWS OF ANTIGUA) ACT" (PDF). Laws.gov.ag. Archived (PDF) from the original on 8 June 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Chapter 304: The Parish Boundaries Act". Laws of Antigua and Barbuda (PDF). laws.gov.ag. 17 December 1873. Archived (PDF) from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 14 April 2022.

- ^ "Population projections by age group, annual 1991 to 2026". Statistics Division, Ministry of Finance and Corporate Governance of Antigua and Barbuda. Archived from the original on 27 June 2022.

- ^ a b "World Economic Outlook October 2023 (Antigua and Barbuda)". International Monetary Fund. October 2023. Retrieved 13 December 2023.

- ^ "Human Development Report 2023/24" (PDF). United Nations Development Programme. 13 March 2024. pp. 274–277. Retrieved 15 March 2024.

- ^ "Government of Antigua and Barbuda". Archived from the original on 3 May 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Horsford, Ian. "An Assessment of Income Inequality and Poverty in Antigua and Barbuda in 2007". Archived from the original on 18 April 2022. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ "Comparison of Poverty measurement indicators" (PDF). Economic Commission for Latin America (ECLA). 2006. Archived (PDF) from the original on 2 May 2021. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Antigua and Barbuda". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 January 2021. (Archived 2021 edition.)

- ^ a b Crocker, John. "Barbuda Eyes Statehood and Tourists". The Washington Post. 28 January 1968. p. E11.

- ^ Fleck, Bryan. "Discover Unspoiled: Barbuda". Everybody's Brooklyn. 31 October 2004. p. 60.

- ^ Sheridan, Richard B. (1974). Sugar and Slavery: An Economic History of the British West Indies, 1623–1775. Canoe Press. p. 185. ISBN 978-976-8125-13-2. Archived from the original on 24 February 2021. Retrieved 10 November 2018.

- ^ "Antigua and Barbuda – Countries – Office of the Historian". history.state.gov. Archived from the original on 7 June 2022. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal:Antique and Barbuda". World Bank. Archived from the original on 30 January 2021. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Passport of Antigua and Barbuda | Rank = 23 | Passport Index 2022 | How powerful is yours?". Passport Index – Global Mobility Intelligence. Archived from the original on 31 March 2022. Retrieved 23 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Individual Income Tax Rates Table – KPMG Global". KPMG. 11 November 2020. Archived from the original on 1 May 2021. Retrieved 6 May 2021.

- ^ IT (3 March 2020). "History Of Antigua – Antigua And Barbuda". Antigua and Barbuda Embassy in Madrid – Ambassador Dario Item. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Niddrie, David Lawrence; Momsen, Janet D.; Tolson, Richard. "Antigua and Barbuda". Encyclopædia Britannica. Archived from the original on 3 April 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ a b c d e f g h "Antigua and Barbuda : History". The Commonwealth. Archived from the original on 24 June 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Napolitano, Matthew F.; DiNapoli, Robert J.; Stone, Jessica H.; Levin, Maureece J.; Jew, Nicholas P.; Lane, Brian G.; O'Connor, John T.; Fitzpatrick, Scott M. (18 December 2019). "Reevaluating human colonization of the Caribbean using chronometric hygiene and Bayesian modeling". Science Advances. 5 (12): eaar7806. Bibcode:2019SciA....5R7806N. doi:10.1126/sciadv.aar7806. ISSN 2375-2548. PMC 6957329. PMID 31976370.

- ^ "Caribbean Trade and Networks (U.S. National Park Service)". nps.gov. Retrieved 19 July 2022.

- ^ Duval, D. T. (1996). Saladoid archaeology on St. Vincent, West Indies: results of the 1993/1994 University of Manitoba survey

- ^ Austin Alchon, Suzanne (2003). A pest in the land: new world epidemics in a global perspective. University of New Mexico Press. pp. 62–63. ISBN 0-8263-2871-7. Archived from the original on 29 November 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

- ^ "Antigua's Disputed Slave Conspiracy of 1736". Archived from the original on 8 July 2019. Retrieved 8 July 2019.

- ^ Kras, Sara Louise (2008). Antigua and Barbuda. Cultures of the World. Vol. 26. Marshall Cavendish. p. 18. ISBN 9780761425700. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 11 September 2020.

a cableway using baskets was built to transfer the mined phosphate to a pier for shipping

- ^ "Antiguan Quits in Weapons Scandal". Sun-Journal. 26 April 1990. Archived from the original on 31 May 2022. Retrieved 4 July 2011.

- ^ "Antigua-Barbuda: Government Finally Orders Probe of Arms Shipment". IPS-Inter Press Service. 25 April 1990.

- ^ Massiah, David (7 May 1995). "Younger Brother of Prime Minister Lester Bird Is Arrested on Cocaine Charges". Associated Press Worldstream. Associated Press.

- ^ Massiah, David (8 May 1995). "Prime Minister Lester Bird Promises No Intervention in Brother's Arrest". Associated Press Worldstream. Associated Press.

- ^ "20th Anniversary of Hurricane Luis". Anumetservice.wordpress.com. 5 September 2015. Archived from the original on 12 September 2017. Retrieved 30 September 2017.

- ^ "Caribbean Elections Biography | Winston Baldwin Spencer". www.caribbeanelections.com. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ Charles, Jacqueline. "Browne becomes new prime minister of Antigua, youngest ever". The Miami Herald. Archived from the original on 14 July 2014. Retrieved 14 June 2014.

- ^ "Speculation about early election in Antigua". Barbados Today. 12 June 2021. Archived from the original on 18 December 2021. Retrieved 29 December 2021.

- ^ "Nelson's Dockyard in Antigua now a Unesco heritage site: Travel Weekly". travelweekly.com.

- ^ Panzar, Javier; Willsher, Kim (9 September 2017). "Hurricane Irma leaves Caribbean Islands Devastated". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ John, Tara (11 September 2017). "Hurricane Irma Flattens Barbuda, Leaving Population Stranded". Time. Archived from the original on 7 August 2020. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ Boger, Rebecca; Perdikaris, Sophia (11 February 2019). "After Irma, Disaster Capitalism Threatens Cultural Heritage in Barbuda". NACLA. Archived from the original on 25 December 2021. Retrieved 1 September 2020.

- ^ "Largest cities in Antigua and Barbuda". Mongabay. Archived from the original on 12 January 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Urban Population (%of total population)". The World Bank. Archived from the original on 7 November 2017. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ "Antigua and Barbuda – Urban Population". Index Mundi. Archived from the original on 18 April 2021. Retrieved 3 February 2021.

- ^ Hanna, Jason; Sterling, Joe; Almasy, Steve (6 September 2017). "Hurricane Irma: Powerful storm blamed for three deaths". ABS TV Radio Antigua & Barbuda. CNN. Archived from the original on 24 June 2018. Retrieved 6 September 2017.

- ^ Panzar, Javier (9 September 2017). "Hurricane Irma leaves Caribbean islands devastated". Los Angeles Times. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ John, Tara /. "'There Is No Home to Go Back to.' Hurricane Irma Flattens Barbuda, Leaving Population Stranded". Time. Archived from the original on 11 September 2017. Retrieved 11 September 2017.

- ^ "World Bank Climate Change Knowledge Portal". climateknowledgeportal.worldbank.org. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "Deforestation statistics for Antigua and Barbuda". RainForests Mongabay. Retrieved 24 November 2020.

- ^ "Vulnerability of Eastern Caribbean Countries - World". ReliefWeb. Retrieved 25 November 2020.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022". United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "World Population Prospects 2022: Demographic indicators by region, subregion and country, annually for 1950-2100" (XSLX) ("Total Population, as of 1 July (thousands)"). United Nations Department of Economic and Social Affairs, Population Division. Retrieved 17 July 2022.

- ^ "Background Note: Antigua and Barbuda". state.gov. Archived from the original on 22 January 2017. Retrieved 23 August 2007.

- ^ "ECLAC/CELADE Redatam+SP 11/12/2022" (PDF). redatam.org. Archived from the original (PDF) on 12 November 2022. Retrieved 12 November 2022.

- ^ Farquhar, Bernadette, "The Spanish Language in Antigua and Barbuda: Implications for Language Planning and Language Research" Archived 15 July 2013 at the Wayback Machine

- ^ "Antigua and Barbuda" Archived 2008-09-26 at the Wayback Machine. 2001 Findings on the Worst Forms of Child Labor. Bureau of International Labor Affairs, U.S. Department of Labor (2002). This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain.

- ^ "Meet your Minister - Daryll Matthew". Antigua News. 20 January 2023. Archived from the original on 20 January 2023.

- ^ "Literacy rate, adult total (% of people ages 15 and above) - Antigua and Barbuda | Data". data.worldbank.org. Retrieved 10 December 2022.

- ^ "Education Statistics (EdStats): Antigua and Barbuda". The World Bank. 2022. Archived from the original on 2 July 2023.

- ^ a b c

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Antigua and Barbuda". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 January 2021. (Archived 2021 edition.)

This article incorporates text from this source, which is in the public domain: "Antigua and Barbuda". The World Factbook (2024 ed.). Central Intelligence Agency. Retrieved 24 January 2021. (Archived 2021 edition.)

- ^ "Antigua and Barbuda - CLGF". www.clgf.org.uk. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ Antigua & Barbuda: Foreign Policy & Government Guide. International Business Publications, USA. May 2004. ISBN 0-7397-9643-7.

- ^ a b c d e "The Antigua and Barbuda Constitution Order 1981" (PDF).

- ^ "Antigua Constitution Order 1967" (PDF).

- ^ "Countries". Commonwealth Governance. Retrieved 10 September 2023.

- ^ 2018 Referendum Results ABEC

- ^ "Magistrate's Code of Procedure Act" (PDF).

- ^ "Eastern Caribbean Supreme Court". www.eccourts.org. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ a b "АНТИГУА И БАРБУДА | Энциклопедия Кругосвет". www.krugosvet.ru (in Russian). Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "Local Government". Barbudaful.

- ^ "Antigua and Barbuda 2018 Labour Force Survey Report" (PDF). Antigua & Barbuda Statistics Division (statistics.gov.ag). October 2020. Retrieved 3 September 2022.

Table 6.2.1

- ^ The Laws of the Island of Antigua: Consisting of the Acts of the Leeward Islands, Commencing 8. Novem. 1690 Ending 21. April 1798, and the Acts of Antigua Commencing 10. April 1668, Ending 7. May 1804 : with Prefixed to Each Volume, Analytical Tables of the Titles of the Acts, and at the End of the Whole, a Copious Digested Index. Bagster. 1805.

- ^ "Manifesto". Asot A Michael. Retrieved 19 January 2023.

- ^ "Policy Highlight: Parish Councils" (PDF).

- ^ "Redonda Annexation Act" (PDF).

- ^ "Voice, Participation and Governance: The Case of the Eastern Caribbean". web.worldbank.org. Retrieved 6 January 2023.

- ^ jennelsa.johnson (12 March 2020). "The political Neanderthal". Antigua Observer Newspaper. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Hurst Says Request For Barbuda To Separate Is "Nonsense Talk"". Antigua News Room. 4 September 2020. Retrieved 22 June 2024.

- ^ "The Public Health Act" (PDF).

- ^ Abbott, W.J. (13 August 1914). "At a meeting of the Saint John's City Commissioners held at their office in Church Lane on Thursday the 16th day of July, 1914" (PDF). The Leeward Islands Gazette. pp. 272–273. Archived (PDF) from the original on 24 June 2024. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "St. John's Development Corporation Act" (PDF).

- ^ "Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Agriculture, Trade & Barbuda Affairs | Montevideo Consensus on Population and Development". consensomontevideo.cepal.org. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Government of Antigua and Barbuda". ab.gov.ag. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Administrator, OECS (18 April 2024). "About Us". Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Nations, United. "Member States". United Nations. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Member States and Associate Members". Caribbean Community.

- ^ "Member States – AOSIS". Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "WTO Members and Observers". www.wto.org. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Reporter, Didi Kirsten Tatlow Senior; Investigations, International Affairs / (20 April 2024). "Antigua says it is a friend of both U.S. and China, after Newsweek article". Newsweek. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Facebook". www.facebook.com. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Small island development 'a test case' for climate and financial justice, says Guterres | UN News". news.un.org. 27 May 2024. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ Radio, ABS TV / (18 June 2024). "UNITED NATIONS PRAISES ANTIGUA & BARBUDA'S MULTILATERALISM EFFORTS - ABS TV Radio Antigua & Barbuda". Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Antigua and Barbuda and Montserrat Forge Closer Ties". Caribbean Community.

- ^ "Antigua wants Montserrat refugee help". United Press International. 23 August 1997.

- ^ "Unvaccinated Travelers To and From Montserrat Given the Green Light to Transit through Antigua". ZJB Radio: Community Radio At Its Best. 8 March 2022. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Government of Antigua and Barbuda". ab.gov.ag. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Government of Antigua and Barbuda". ab.gov.ag. Retrieved 23 June 2024.

- ^ "Defence Act" (PDF).

- ^ "National Security Council Act" (PDF).

- ^ "Police Act" (PDF).

- ^ "Special Service Unit". Ministry of Public Safety and Labour.

- ^ ""B" Division". Ministry of Public Safety and Labour.

- ^ Avery, Daniel (4 April 2019). "71 Countries Where Homosexuality is illegal". Newsweek. Archived from the original on 11 December 2019. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "State-Sponsored Homophobia". International Lesbian Gay Bisexual Trans and Intersex Association. 20 March 2019. Archived from the original on 8 February 2020. Retrieved 16 August 2019.

- ^ "Antigua: a Mature Financial Centre". IFC Review. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Krauss, Clifford; Creswell, Julie; Savage, Charlie (21 February 2009). "Fraud Case Shakes a Billionaire's Caribbean Realm". The New York Times. Archived from the original on 16 April 2009. Retrieved 14 April 2010.

- ^ "Manufacturing, value added (% of GDP) – Antigua and Barbuda, Germany | Data". World Bank. Retrieved 11 October 2022.

- ^ Newsdesk (15 September 2021). "Antigua and Barbuda's Tourism Growth Continues". Travel Agent Central. Archived from the original on 16 September 2021. Retrieved 24 April 2022.

- ^ a b "Country Trends". Global Footprint Network. Archived from the original on 8 August 2017. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- ^ Lin, David; Hanscom, Laurel; Murthy, Adeline; Galli, Alessandro; Evans, Mikel; Neill, Evan; Mancini, MariaSerena; Martindill, Jon; Medouar, FatimeZahra; Huang, Shiyu; Wackernagel, Mathis (2018). "Ecological Footprint Accounting for Countries: Updates and Results of the National Footprint Accounts, 2012–2018". Resources. 7 (3): 58. doi:10.3390/resources7030058.

- ^ Citizenship by Investment Unit. "Antigua and Barbuda Citizenship by Investment Program". Antigua and Barbuda. Archived from the original on 2 November 2019. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- ^ McDaniel, pp. 798-800

- ^ a b Luffman, John (1788). A Brief Account of the Island of Antigua. London. cited in McDaniel, pp 798-800

- ^ Antigua and Barbuda's Cultural Heritage Archived 2005-10-26 at the Wayback Machine and McDaniel, pp 798-800

- ^ "A' Design Award and Competition - Design Encyclopedia - History Of Art In Antigua And Barbuda". competition.adesignaward.com. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "Antigua and Barbuda / Pressroom". www.antigua-barbuda.org. Retrieved 16 August 2023.

- ^ "History of Antigua's Carnival". Antigua's Carnival | Antigua Barbuda Festivals Commission. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "Antigua's Carnival". Visit Antigua & Barbuda. 17 September 2018. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ "8 of the best Caribbean carnivals". Travel. 14 July 2023. Retrieved 28 April 2024.

- ^ Beckett, Luisa. Yachting Escapes: The Caribbean. The Escapes Group ltd. p. 50. ISBN 978-1-60643-795-7. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ Vaitilingam, Adam (31 January 2002). The Rough Guide to Antigua and Barbuda. Rough Guides. p. 129. ISBN 978-1-85828-715-7. Retrieved 24 March 2012.

- ^ a b "Antigua and Barbuda Public Holidays". ab.gov.ag. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "the barbudaful community". Barbudaful. Retrieved 22 July 2023.

- ^ "Public Holidays Act" (PDF).

- ^ "ANTIGUA & BARBUDA'S CULTURAL HERITAGE". antiguahistory.net. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Antigua & Barbuda National Dish & Recipe." Archived October 13, 2010, at the Wayback Machine Recipeisland.com. Accessed July 2011.

- ^ "Antigua Black Pineapple | Local Pineapple From Antigua and Barbuda". www.tasteatlas.com. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "The Antigua Black Pineapple: An Island Treasure | Sandals Blog". Hello Paradise - The Official Sandals Resorts Travel & Lifestyle Blog. 2 January 2019. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ admin (1 June 2016). "Antigua Sunday Bread". Cooking Sense Magazine. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Antigua's traditional bread shops struggle amid food price hikes". BBC News. 3 September 2022. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ ChainBaker (2 May 2021). "Antiguan Raisin Buns, Unique Bun & Cheese Recipe". ChainBaker. Retrieved 5 February 2023.

- ^ "Viv Richards was a complete genius: Imran Khan". Dawn. Pakistan. 2 April 2011. Retrieved 25 January 2021.

- ^ Featured Columnist (13 November 2013). "The ICC Ranking System's Top 10 Batsmen in ODI Cricket History". Bleacher Report. Retrieved 7 August 2014.

- ^ "ACB Antigua Parish League". Cricket268. 20 January 2024. Retrieved 24 June 2024.

- ^ "Antigua & Barbuda taking small steps towards respectability | World Soccer". worldsoccer.com. Archived from the original on 24 March 2014. Retrieved 25 March 2014.

- ^ "ANTIGUA AND BARBUDA". Concacaf. 7 March 2021. Retrieved 16 April 2024.

Further reading

[edit]- Nicholson, Desmond V., Antigua, Barbuda, and Redonda: A Historical Sketch, St. Johns, Antigua: Antigua and Barbuda Museum, 1991.

- Dyde, Brian, A History of Antigua: The Unsuspected Isle, London: Macmillan Caribbean, 2000.

- Gaspar, David Barry – Bondmen & Rebels: A Study of Master-Slave Relations in Antigua, with Implications for Colonial America.

- Harris, David R. – Plants, Animals, and Man in the Outer Leeward Islands, West Indies. An Ecological Study of Antigua, Barbuda, and Anguilla.

- Henry, Paget – Peripheral Capitalism and Underdevelopment in Antigua.

- Lazarus-Black, Mindie – Legitimate Acts and Illegal Encounters: Law and Society in Antigua and Barbuda.

- Riley, J. H. – Catalogue of a Collection of Birds from Barbuda and Antigua, British West Indies.

- Rouse, Irving and Birgit Faber Morse – Excavations at the Indian Creek Site, Antigua, West Indies.

- Thomas Hearne. Southampton.

External links

[edit]- The Official Website of the Government of Antigua and Barbuda

Wikimedia Atlas of Antigua and Barbuda

Wikimedia Atlas of Antigua and Barbuda- Antigua and Barbuda, United States Library of Congress

- Antigua and Barbuda. The World Factbook. Central Intelligence Agency.

- Antigua and Barbuda from UCB Libraries GovPubs

- Antigua and Barbuda at Curlie

- Antigua and Barbuda from the BBC News

- World Bank's country data profile for Antigua and Barbuda

- ArchaeologyAntigua.org – 2010March13 source of archaeological information for Antigua and Barbuda

- Antigua & Barbuda Official Business Hub

- Antigua and Barbuda

- Countries in the Caribbean

- Island countries

- Commonwealth realms

- Countries in North America

- Countries and territories where English is an official language

- Member states of the Caribbean Community

- Member states of the Commonwealth of Nations

- Member states of the Organisation of Eastern Caribbean States

- Member states of the United Nations

- Small Island Developing States

- British Leeward Islands

- Former British colonies and protectorates in the Americas

- Former colonies in North America

- 1630s establishments in the Caribbean

- 1632 establishments in the British Empire

- 1981 disestablishments in the United Kingdom

- States and territories established in 1981

- 1981 establishments in Antigua and Barbuda