Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi | |

|---|---|

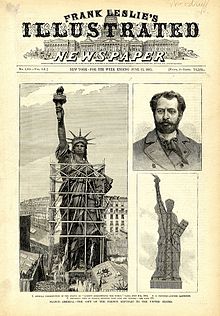

Portrait by Nadar, c. 1875 | |

| Born | 2 August 1834 Colmar, France |

| Died | 4 October 1904 (aged 70) Paris, France |

| Resting place | Montparnasse Cemetery |

| Education | Lycee Louis-le-Grand |

| Alma mater | École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts |

| Notable work | Statue of Liberty |

| Spouse |

Jeanne-Emile Baheux (m. 1876) |

| Signature | |

Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi (/bɑːrˈtɒldi, -ˈθɒl-/ bar-T(H)OL-dee,[1][2] French: [fʁedeʁik oɡyst baʁtɔldi]; 2 August 1834 – 4 October 1904) was a French sculptor and painter. He is best known for designing Liberty Enlightening the World, commonly known as the Statue of Liberty.[3]

Early life and education

[edit]

Bartholdi was born in Colmar, France, on August 2, 1834.[4] He was born to a family of Alsatian Protestant heritage, with his family name adopted from Barthold.[5] His parents were Jean Charles Bartholdi (1791–1836) and Augusta Charlotte Bartholdi (née Beysser; 1801–1891). Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi was the youngest of their four children, and one of only two to survive infancy, along with the oldest brother, Jean-Charles, who became a lawyer and editor.[citation needed]

Bartholdi's father, a property owner and counselor to the prefecture, died when Bartholdi was two years old.[5] Afterwards, Bartholdi moved with his mother and his older brother Jean-Charles to Paris, where another branch of their family resided.[5] With the family often returning to spend long periods of time in Colmar,[5] the family maintained ownership and visited their house in Alsace, which later became the Bartholdi Museum in 1922.[6] While in Colmar, Bartholdi took drawing lessons from Martin Rossbach. In Paris, he studied sculpture with Antoine Étex. He also studied architecture under Henri Labrouste and Eugène-Emmanuel Viollet-le-Duc.[5]

Bartholdi attended the Lycée Louis-le-Grand in Paris and received a baccalauréat in 1852. He then went on to study architecture at the École nationale supérieure des Beaux-Arts[citation needed] as well as painting under Ary Scheffer[3][5] in his studio in the Rue Chaptal, now the Musée de la Vie Romantique.[citation needed] Later, Bartholdi turned his attention to sculpture, which afterward exclusively occupied him and his life.[3]

Career

[edit]Early sculptures and work in Colmar

[edit]

In 1853, Bartholdi submitted a Good Samaritan-themed sculptural group to the Paris Salon of 1853. The statue was later recreated in bronze. Within two years of his Salon debut, Bartholdi was commissioned by his hometown of Colmar to sculpt a bronze memorial of Jean Rapp, a Napoleonic General.[5] In 1855 and 1856, Bartholdi traveled in Yemen and Egypt with travel companions such as Jean-Léon Gérôme and other "orientalist" painters. The trip sparked Bartholdi's interest in colossal sculpture.[5]

In 1869, Bartholdi returned to Egypt to propose a new lighthouse to be built at the entrance of the Suez Canal, which was newly completed. The lighthouse, which was to be called Egypt Carrying the Light to Asia and shaped as a massive, draped figure holding a torch, was not commissioned.[5] Both the khedive and Lesseps declined the proposed statue from Bartholdi, citing the high cost.[7] The Port Said Lighthouse was built instead, by François Coignet in 1869.

The war and Statue of Liberty

[edit]

Bartholdi served in the Franco-Prussian War of 1870 as a squadron leader of the National Guard, and as a liaison officer to Italian General Giuseppe Garibaldi, representing the French government and the Army of the Vosges.[citation needed] As an officer, he took part in the defense of Colmar from Germany. Distraught over his region's defeat, over the following years he constructed a number of monuments celebrating French heroism in the defense against Germany. Among these projects was the Lion of Belfort, which he started working on in 1871, not finishing the massive sandstone statue until 1880.[5]

In 1871, he made his first trip to the United States, where he pitched the idea of a massive statue gifted from the French to the Americans in honor of the centennial of American independence. The idea, which had first been broached to him in 1865 by his friend Édouard René de Laboulaye, resulted in the Statue of Liberty in New York Harbor.[5] After years of work and fundraising, the statue was inaugurated in 1886.[5] During this period, Bartholdi also sculpted monuments for other American cities, such as the Bartholdi Fountain in Washington, D.C., completed in 1878.[5]

Later years

[edit]In 1875, he joined the Freemasons Lodge Alsace-Lorraine in Paris.[8][9] In 1876, Bartholdi was one of the French commissioners in 1876 to the Philadelphia Centennial Exposition. There he exhibited bronze statues of The Young Vine-Grower, Génie Funèbre, Peace and Genius in the Grasp of Misery, receiving a bronze medal for the latter.[3] His 1878 statue Gribeauval became the property of the French state.[3]

A prolific creator of statues, monuments, and portraits, Bartholdi exhibited at the Paris Salons until the year of his death in 1904.[5] He also remained active with diverse mediums, including oil painting, watercolor, photography, and drawing,[5] and received the rank of Commander of the Legion of Honor in 1886. Bartholdi died of tuberculosis at age 70 in Paris on October 4, 1904.[10]

Personal life

[edit]In 1876, he married Jeanne-Emile Baheux in Providence, Rhode Island.[5] In 1893, Bartholdi and his wife visited the 1893 World's Columbian Exposition in Chicago, where his Washington and Lafayette sculptural group was exhibited.[11] Throughout his life Bartholdi maintained his childhood family home in Colmar; in 1922, it was made into the Musée Bartholdi.[5]

Major projects

[edit]The Statue of Liberty (Liberty Enlightening the World)

[edit]

The work for which Bartholdi is most famous is Liberty Enlightening the World, better known as the Statue of Liberty. Soon after the establishment of the French Third Republic, the project of building some suitable memorial to show the fraternal feeling existing between the republics of the United States and France was suggested, and in 1874 the Union Franco-Américaine (Franco-American Union) was established by Edouard de Laboulaye.[3]

Bartholdi's hometown in Alsace had just passed into German control in the Franco-Prussian War. These troubles in his ancestral home of Alsace are purported to have further influenced Bartholdi's own great interest in independence, liberty, and self-determination.[citation needed] Bartholdi subsequently joined the Union Franco-Américaine, among whose members were Laboulaye, Paul de Rémusat, William Waddington, Henri Martin, Ferdinand Marie de Lesseps, Jean-Baptiste Donatien de Vimeur, comte de Rochambeau, Oscar Gilbert Lafayette,[3] François Charles Lorraine, and Louis François Lorraine.[clarification needed]

Bartholdi broached the idea of a massive statue and once its design was approved, the Union Franco-Américaine raised more than 1 million francs throughout France for its building.[3] In 1879, Bartholdi was awarded design patent U.S. patent D11,023 for the Statue of Liberty.[clarification needed] On July 4, 1880, the statue was formally delivered to the American minister in Paris, the event being celebrated by a great banquet.[3] In October 1886, the structure was officially presented as the joint gift of the French and American people, and installed on Bedloe's Island in New York Harbor.[3] It was rumored in France that the face of the Statue of Liberty was modeled after Bartholdi's mother.[12] The statue is 46 metres (151 ft),[13] and the top of the torch is at an elevation of 93 metres (305 ft) from mean low-water mark.[14] It was the largest work of its kind that had been completed up to that time.[3]

Works in Colmar

[edit]

Bartholdi's hometown Colmar (modern political administrative region of Grand Est) has a number of statues and monuments by the sculptor, as well as a museum founded in 1922 in the house in which he was born, at 30 Rue des Marchands.

- Monument du Général Rapp – 1856 (first shown 1855 in Paris. Bartholdi's earliest major work)

- "Fontaine Schongauer" – 1863 (in front of the Unterlinden Museum)

- "Fontaine de l'Amiral Bruat" – 1864

- "Fontaine Roeselmann" – 1888

- "Monument Hirn" – 1894

- "Fontaine Schwendi", depicting Lazarus von Schwendi – 1898

- Les grands soutiens du monde − 1902 (statue in the courtyard of the museum)

Other major works

[edit]

Bartholdi's other major works include a variety of statues at Clermont-Ferrand; in Paris, and in other places. Notable works include:

- 1852: Francesca da Rimini[3]

- 1870: Le Vigneron[3]

- 1876 (plaster version in 1874) : Frieze and four angelic trumpeters on the tower of Brattle Square Church, Boston, Massachusetts, United States.

- 1876: Marquis de Lafayette (or Lafayette Arriving in America),[3] executed 1872, cast 1873[15] in Union Square, New York City, United States.

- 1878: The Bartholdi Fountain in Bartholdi Park, the United States Botanic Garden, Washington, D.C., United States.

- 1880: The Lion of Belfort, in Belfort, France, a massive sculpture of a lion depicting the huge struggle of the French to hold off the Prussian assault at the end of the Franco-Prussian War.[3] A plaster was exhibited in 1878.[3] Bartholdi was an officer himself during this period, attached to Garibaldi.

- 1889: Switzerland Succoring Strasbourg at Basel, Switzerland, which was a gift from the French city of Strasbourg, in appreciation of the humanitarian help it had received during the Franco-Prussian War.

- 1890: Statue of Liberty in Potosí, Bolivia.

- 1892: Fontaine Bartholdi, on the Place des Terreaux, in Lyon, France.

- 1893: Statue of Christopher Columbus, cast in silver for the 1892 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Illinois; a bronze replica was erected in Providence, Rhode Island in 1893 and was taken down in June 2020.[16][17]

- 1895: Lafayette and Washington Monument," in the Place des États-Unis, Paris, and an exact replica at Morningside Park, New York City, United States.

- 1903: Vercingetorix,[3] equestrian statue in Place de Jaude, Clermont-Ferrand.

-

Bartholdi's Lion of Belfort

-

Vercingetorix, Place de Jaude, Clermont-Ferrand.

-

Columbus statue, Providence, Rhode Island, erected 1892, removed 2020

-

Switzerland Succoring Strasbourg in Basel, Switzerland

-

Ancient California, painting in the Musée Bartholdi, Colmar. Height 150 cm (59 in), width 200 cm (79 in). Between 1871 and 1876.

-

The New California, pendant of the preceding work. Same dimensions and inception.

In popular culture

[edit]The Statue of Liberty is a 1985 documentary film by Ken Burns which focuses on the statue's history and its impact on society.

Bartholdi's life and creation of Liberty Enlightening the World are also featured in the 2019 documentary film, Liberty: Mother of Exiles.

In the youtube series The Monument Mythos, various episodes in the first season document his life and works.

See also

[edit]References

[edit]Notes

- ^ "Bartholdi". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- ^ "Bartholdi, Auguste". Lexico UK English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on 25 September 2020.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

- ^ "Biographie". musee-bartholdi.fr. Musée Bartholdi, Colmar. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q "Bartholdi, Frédéric-Auguste". www.nga.gov. National Gallery of Art. Retrieved 5 August 2016.

- ^ Schenk, Peter (30 March 2016). "Mein Leben im Dreiland: Die Freiheitsstatue steht in Colmar | bz Basel". bz - Zeitung für die Region Basel (in German). Retrieved 15 February 2021.

- ^ Karabell, Zachary (2003). Parting the desert: the creation of the Suez Canal. Alfred A. Knopf. p. 243. ISBN 0-375-40883-5.

- ^ Moreno, Barry (10 November 2004). The Statue of Liberty. Arcadia Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4396-3220-8.

- ^ Giuseppe Seganti, Massoni Famosi, Rome, Atanòr, 2005, ISBN 88-7169-223-3.

- ^ "1904, Décès, 06" (in French). Archives de Paris. pp. 30–31. Retrieved 14 November 2020.

- ^ "Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi's Visit to the 1893 Columbian Exposition in Chicago, Part 1". Chicagos 1893 Worlds Fair. 5 July 2021. Retrieved 12 September 2022.

- ^ "Frequently Asked Questions About the Statue of Liberty" on the United States National Park Service's Statue of Liberty website

- ^ Scoboria, Evan (6 May 2023). "Guide to the Statue of Liberty's Dimensions (Height, Weight, and More)". SKNY. Retrieved 23 November 2023.

- ^ "Statue of Liberty: Frequently Asked Questions", National Park Service website

- ^ "Union Square Highlights" on the New York City Parks Department website

- ^ Amaral, Brian (25 June 2020). "Providence removes statue of Christopher Columbus, its fate unclear". The Providence Journal. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

- ^ "Dedication of the Bartholdi statue of Columbus". Brown University Library. Brown University. Retrieved 29 June 2020.

Sources

- Wilson, J. G.; Fiske, J., eds. (1900). . Appletons' Cyclopædia of American Biography. New York: D. Appleton.

Further reading

[edit]- Belot, Robert; Daniel Bermond (2004). Bartholdi.

- Blanchet, Christian. Statue of Liberty: The First Hundred Years (American Heritage Publishing Co., 1985).

- Durante, Dianne (2007). Outdoor Monuments of Manhattan: A Historical Guide. New York University Press.

- Gschaedler, Andre (1966). True Light on the Statue of Liberty and Her Creator.

- Moreno, Barry (2000). The Statue of Liberty Encyclopedia. New York: Simon & Schuster. ISBN 0-684-86227-1.

- New York Public Library. Liberty: the French-American statue in art and history (Harper & Row, 1986).

- Price, Willadene. Bartholdi and the Statue of Liberty (Rand McNally, 1959).

External links

[edit]- Biography by the National Gallery of Art

- The Bartholdi Fountain and Bartholdi Park – Washington, DC

- The Musée Bartholdi (in French)

- The Statue of Liberty Enlightning the World, described by the sculptor Frédéric Bartholdi

- Works by or about Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi at the Internet Archive

- Works by Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Frédéric Auguste Bartholdi in American public collections, on the French Sculpture Census website

- 1834 births

- 1904 deaths

- People from Colmar

- Alsatian-German people

- 20th-century deaths from tuberculosis

- French Freemasons

- Statue of Liberty

- Tuberculosis deaths in France

- French military personnel of the Franco-Prussian War

- Burials at Montparnasse Cemetery

- Commanders of the Legion of Honour

- 19th-century French sculptors

- French male sculptors