Electrode

An electrode is an electrical conductor used to make contact with a nonmetallic part of a circuit (e.g. a semiconductor, an electrolyte, a vacuum or air). Electrodes are essential parts of batteries that can consist of a variety of materials (chemicals) depending on the type of battery.

The electrophore, invented by Johan Wilcke, was an early version of an electrode used to study static electricity.[1]

Anode and cathode in electrochemical cells

[edit]

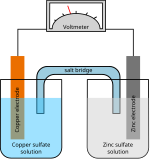

Electrodes are an essential part of any battery. The first electrochemical battery was devised by Alessandro Volta and was aptly named the Voltaic cell.[2] This battery consisted of a stack of copper and zinc electrodes separated by brine-soaked paper disks. Due to fluctuation in the voltage provided by the voltaic cell, it was not very practical. The first practical battery was invented in 1839 and named the Daniell cell after John Frederic Daniell. It still made use of the zinc–copper electrode combination. Since then, many more batteries have been developed using various materials. The basis of all these is still using two electrodes, anodes and cathodes.

Anode (-)

[edit]'Anode' was coined by William Whewell at Michael Faraday's request, derived from the Greek words ἄνο (ano), 'upwards' and ὁδός (hodós), 'a way'.[3] The anode is the electrode through which the conventional current enters from the electrical circuit of an electrochemical cell (battery) into the non-metallic cell. The electrons then flow to the other side of the battery. Benjamin Franklin surmised that the electrical flow moved from positive to negative.[4] The electrons flow away from the anode and the conventional current towards it. From both can be concluded that the charge of the anode is negative. The electron entering the anode comes from the oxidation reaction that takes place next to it.

Cathode (+)

[edit]The cathode is in many ways the opposite of the anode. The name (also coined by Whewell) comes from the Greek words κάτω (kato), 'downwards' and ὁδός (hodós), 'a way'. It is the positive electrode, meaning the electrons flow from the electrical circuit through the cathode into the non-metallic part of the electrochemical cell. At the cathode, the reduction reaction takes place with the electrons arriving from the wire connected to the cathode and are absorbed by the oxidizing agent.

Primary cell

[edit]

A primary cell is a battery designed to be used once and then discarded. This is due to the electrochemical reactions taking place at the electrodes in the cell not being reversible. An example of a primary cell is the discardable alkaline battery commonly used in flashlights. Consisting of a zinc anode and a manganese oxide cathode in which ZnO is formed.

The half-reactions are:

- Zn(s) + 2OH−(aq) → ZnO(s) + H2O(l) + 2e− [E0oxidation = -1.28 V]

- 2MnO2(s) + H2O(l) + 2e− → Mn2O3(s) + 2OH−(aq) [E0reduction = +0.15 V]

Overall reaction:

- Zn(s) + 2MnO2(s) ⇌ ZnO(s) + Mn2O3(s) [E0total = +1.43 V]

The ZnO is prone to clumping and will give less efficient discharge if recharged again. It is possible to recharge these batteries but is due to safety concerns advised against by the manufacturer. Other primary cells include zinc–carbon, zinc–chloride, and lithium iron disulfide.

Secondary cell

[edit]

Contrary to the primary cell a secondary cell can be recharged. The first was the lead–acid battery, invented in 1859 by French physicist Gaston Planté. This type of battery is still the most widely used in among others automobiles.[5] The cathode consists of lead dioxide (PbO2) and the anode of solid lead. Other commonly used rechargeable batteries are nickel–cadmium, nickel–metal hydride, and Lithium-ion. The last of which will be explained more thoroughly in this article due to its importance.

Marcus' theory of electron transfer

[edit]Marcus theory is a theory originally developed by Nobel laureate Rudolph A. Marcus and explains the rate at which an electron can move from one chemical species to another,[6] for this article this can be seen as 'jumping' from the electrode to a species in the solvent or vice versa. We can represent the problem as calculating the transfer rate for the transfer of an electron from donor to an acceptor

- D + A → D+ + A−

The potential energy of the system is a function of the translational, rotational, and vibrational coordinates of the reacting species and the molecules of the surrounding medium, collectively called the reaction coordinates. The abscissa the figure to the right represents these. From the classical electron transfer theory, the expression of the reaction rate constant (probability of reaction) can be calculated, if a non-adiabatic process and parabolic potential energy are assumed, by finding the point of intersection (Qx). One important thing to note, and was noted by Marcus when he came up with the theory, the electron transfer must abide by the law of conservation of energy and the Frank-Condon principle. Doing this and then rearranging this leads to the expression of the free energy activation () in terms of the overall free energy of the reaction ().

In which the is the reorganisation energy. Filling this result in the classically derived Arrhenius equation

leads to

With A being the pre-exponential factor which is usually experimentally determined,[7] although a semi classical derivation provides more information as will be explained below.

This classically derived result qualitatively reproduced observations of a maximum electron transfer rate under the conditions .[8] For a more extensive mathematical treatment one could read the paper by Newton.[9] An interpretation of this result and what a closer look at the physical meaning of the one can read the paper by Marcus.[10]

the situation at hand can be more accurately described by using the displaced harmonic oscillator model, in this model quantum tunneling is allowed. This is needed in order to explain why even at near-zero Kelvin there still are electron transfers,[11] in contradiction to the classical theory.

Without going into too much detail on how the derivation is done, it rests on using Fermi's golden rule from time-dependent perturbation theory with the full Hamiltonian of the system. It is possible to look at the overlap in the wavefunctions of both the reactants and the products (the right and the left side of the chemical reaction) and therefore when their energies are the same and allow for electron transfer. As touched on before this must happen because only then conservation of energy is abided by. Skipping over a few mathematical steps the probability of electron transfer can be calculated (albeit quite difficult) using the following formula

With being the electronic coupling constant describing the interaction between the two states (reactants and products) and being the line shape function. Taking the classical limit of this expression, meaning , and making some substitution an expression is obtained very similar to the classically derived formula, as expected.

The main difference is now the pre-exponential factor has now been described by more physical parameters instead of the experimental factor . One is once again revered to the sources as listed below for a more in-depth and rigorous mathematical derivation and interpretation.

Efficiency

[edit]The physical properties of electrodes are mainly determined by the material of the electrode and the topology of the electrode. The properties required depend on the application and therefore there are many kinds of electrodes in circulation. The defining property for a material to be used as an electrode is that it be conductive. Any conducting material such as metals, semiconductors, graphite or conductive polymers can therefore be used as an electrode. Often electrodes consist of a combination of materials, each with a specific task. Typical constituents are the active materials which serve as the particles which oxidate or reduct, conductive agents which improve the conductivity of the electrode and binders which are used to contain the active particles within the electrode. The efficiency of electrochemical cells is judged by a number of properties, important quantities are the self-discharge time, the discharge voltage and the cycle performance. The physical properties of the electrodes play an important role in determining these quantities. Important properties of the electrodes are: the electrical resistivity, the specific heat capacity (c_p), the electrode potential and the hardness. Of course, for technological applications, the cost of the material is also an important factor.[12] The values of these properties at room temperature (T = 293 K) for some commonly used materials are listed in the table below.

| Properties | Lithium (Li) | Manganese (Mn) | Copper (Cu) | Zinc (Zn) | Graphite |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Resistivity (Ωm) | 8.40e-8 | 1.44e-6 | 1.70e-8 | 5.92e-8 | 6.00e-6 |

| Electrode potential (V) | -3.02 | -1.05 | -0.340 | -0.760 | - |

| Hardness (HV) | <5 | 500 | 50 | 30 | 7-11 |

| Specific heat capacity (J/(gK)) | 2.997 | 0.448 | 0.385 | 0.3898 | 0.707 |

Surface effects

[edit]The surface topology of the electrode plays an important role in determining the efficiency of an electrode. The efficiency of the electrode can be reduced due to contact resistance. To create an efficient electrode it is therefore important to design it such that it minimizes the contact resistance.

Manufacturing

[edit]The production of electrodes for Li-ion batteries is done in various steps as follows:[14]

- The various constituents of the electrode are mixed into a solvent. This mixture is designed such that it improves the performance of the electrodes. Common components of this mixture are:

- The active electrode particles.

- A binder used to contain the active electrode particles.

- A conductive agent used to improve the conductivity of the electrode.

- The mixture created is known as an ‘electrode slurry’.

- The electrode slurry above is coated onto a conductor which acts as the current collector in the electrochemical cell. Typical current collectors are copper for the cathode and aluminum for the anode.

- After the slurry has been applied to the conductor it is dried and then pressed to the required thickness.

Structure of the electrode

[edit]For a given selection of constituents of the electrode, the final efficiency is determined by the internal structure of the electrode. The important factors in the internal structure in determining the performance of the electrode are:[15]

- Clustering of the active material and the conductive agent. In order for all the components of the slurry to perform their task, they should all be spread out evenly within the electrode.

- An even distribution of the conductive agent over the active material. This makes sure that the conductivity of the electrode is optimal.

- The adherence of the electrode to the current collectors. The adherence makes sure that the electrode does not dissolve into the electrolyte.

- The density of the active material. A balance should be found between the amount of active material, the conductive agent and the binder. Since the active material is the important factor in the electrode, the slurry should be designed such that the density of the active material is as high as possible, without the conductive agent and the binder not functioning properly.

These properties can be influenced in the production of the electrodes in a number of manners. The most important step in the manufacturing of the electrodes is creating the electrode slurry. As can be seen above, the important properties of the electrode all have to do with the even distribution of the components of the electrode. Therefore, it is very important that the electrode slurry be as homogeneous as possible. Multiple procedures have been developed to improve this mixing stage and current research is still being done.[15]

Electrodes in lithium ion batteries

[edit]A modern application of electrodes is in lithium-ion batteries (Li-ion batteries). A Li-ion battery is a kind of flow battery which can be seen in the image on the right.

Furthermore, a Li-ion battery is an example of a secondary cell since it is rechargeable. It can both act as a galvanic or electrolytic cell. Li-ion batteries use lithium ions as the solute in the electrolyte which are dissolved in an organic solvent. Lithium electrodes were first studied by Gilbert N. Lewis and Frederick G. Keyes in 1913.[17] In the following century these electrodes were used to create and study the first Li-ion batteries. Li-ion batteries are very popular due to their great performance. Applications include mobile phones and electric cars. Due to their popularity, much research is being done to reduce the cost and increase the safety of Li-ion batteries. An integral part of the Li-ion batteries are their anodes and cathodes, therefore much research is being done into increasing the efficiency, safety and reducing the costs of these electrodes specifically.[18]

Cathodes

[edit]In Li-ion batteries, the cathode consists of a intercalated lithium compound (a layered material consisting of layers of molecules composed of lithium and other elements). A common element which makes up part of the molecules in the compound is cobalt. Another frequently used element is manganese. The best choice of compound usually depends on the application of the battery. Advantages for cobalt-based compounds over manganese-based compounds are their high specific heat capacity, high volumetric heat capacity, low self-discharge rate, high discharge voltage and high cycle durability. There are however also drawbacks in using cobalt-based compounds such as their high cost and their low thermostability. Manganese has similar advantages and a lower cost, however there are some problems associated with using manganese. The main problem is that manganese tends to dissolve into the electrolyte over time. For this reason, cobalt is still the most common element which is used in the lithium compounds. There is much research being done into finding new materials which can be used to create cheaper and longer lasting Li-ion batteries [18] For example, Chinese and American researchers have demonstrated that ultralong single wall carbon nanotubes significantly enhance lithium iron phosphate cathodes. By creating a highly efficient conductive network that securely binds lithium iron phosphate particles, adding carbon nanotubes as a conductive additive at a dosage of just 0.5 wt.% helps cathodes to achieve a remarkable rate capacity of 161.5 mAh g-1 at 0.5 C and 130.2 mAh g-1 at 5 C, whole maintaining 87.4% capacity retention after 200 cycles at 2 C.[19]

Anodes

[edit]The anodes used in mass-produced Li-ion batteries are either carbon based (usually graphite) or made out of spinel lithium titanate (Li4Ti5O12).[18] Graphite anodes have been successfully implemented in many modern commercially available batteries due to its cheap price, longevity and high energy density.[20] However, it presents issues of dendrite growth, with risks of shorting the battery and posing a safety issue.[21] Li4Ti5O12 has the second largest market share of anodes, due to its stability and good rate capability, but with challenges such as low capacity.[22] During the early 2000s, silicon anode research began picking up pace, becoming one of the decade's most promising candidates for future lithium-ion battery anodes.[23] Silicon has one of the highest gravimetric capacities when compared to graphite and Li4Ti5O12 as well as a high volumetric one. Furthermore, Silicon has the advantage of operating under a reasonable open circuit voltage without parasitic lithium reactions.[24][25] However, silicon anodes have a major issue of volumetric expansion during lithiation of around 360%.[26] This expansion may pulverize the anode, resulting in poor performance.[27] To fix this problem, scientists looked into varying the dimensionality of the Si.[23] Many studies have been developed in Si nanowires, Si tubes as well as Si sheets.[23] As a result, composite hierarchical Si anodes have become the major technology for future applications in lithium-ion batteries. In the early 2020s, technology is reaching commercial levels with factories being built for mass production of anodes in the United States.[28] Furthermore, metallic lithium is another possible candidate for the anode. It boasts a higher specific capacity than silicon, however, does come with the drawback of working with the highly unstable metallic lithium.[29] Similarly to graphite anodes, dendrite formation is another major limitation of metallic lithium, with the solid electrolyte interphase being a major design challenge.[30] In the end, if stabilized, metallic lithium would be able to produce batteries that hold the most charge, while being the lightest.[29]

Mechanical properties

[edit]A common failure mechanism of batteries is mechanical shock, which breaks either the electrode or the system's container, leading to poor conductivity and electrolyte leakage.[31] However, the relevance of mechanical properties of electrodes goes beyond the resistance to collisions due to its environment. During standard operation, the incorporation of ions into electrodes leads to a change in volume. This is well exemplified by Si electrodes in lithium-ion batteries expanding around 300% during lithiation.[32] Such change may lead to the deformations in the lattice and, therefore stresses in the material. The origin of stresses may be due to geometric constraints in the electrode or inhomogeneous plating of the ion.[33] This phenomenon is very concerning as it may lead to electrode fracture and performance loss. Thus, mechanical properties are crucial to enable the development of new electrodes for long lasting batteries. A possible strategy for measuring the mechanical behavior of electrodes during operation is by using nanoindentation.[34] The method is able to analyze how the stresses evolve during the electrochemical reactions, being a valuable tool in evaluating possible pathways for coupling mechanical behavior and electrochemistry.

More than just affecting the electrode's morphology, stresses are also able to impact electrochemical reactions.[33][35] While the chemical driving forces are usually higher in magnitude than the mechanical energies, this is not true for Li-ion batteries.[36] A study by Dr. Larché established a direct relation between the applied stress and the chemical potential of the electrode.[37] Though it neglects multiple variables such as the variation of elastic constraints, it subtracts from the total chemical potential the elastic energy induced by the stress.

In this equation, μ represents the chemical potential, with μ° being its reference value. T stands for the temperature and k the Boltzmann constant. The term γ inside the logarithm is the activity and x is the ratio of the ion to the total composition of the electrode. The novel term Ω is the partial molar volume of the ion in the host and σ corresponds to the mean stress felt by the system. The result of this equation is that diffusion, which is dependent on chemical potential, gets impacted by the added stress and, therefore changes the battery's performance. Furthermore, mechanical stresses may also impact the electrode's solid-electrolyte-interphase layer.[31] The interface which regulates the ion and charge transfer and can be degraded by stress. Thus, more ions in the solution will be consumed to reform it, diminishing the overall efficiency of the system.[38]

Other anodes and cathodes

[edit]In a vacuum tube or a semiconductor having polarity (diodes, electrolytic capacitors) the anode is the positive (+) electrode and the cathode the negative (−). The electrons enter the device through the cathode and exit the device through the anode. Many devices have other electrodes to control operation, e.g., base, gate, control grid.

In a three-electrode cell, a counter electrode, also called an auxiliary electrode, is used only to make a connection to the electrolyte so that a current can be applied to the working electrode. The counter electrode is usually made of an inert material, such as a noble metal or graphite, to keep it from dissolving.

Welding electrodes

[edit]In arc welding, an electrode is used to conduct current through a workpiece to fuse two pieces together. Depending upon the process, the electrode is either consumable, in the case of gas metal arc welding or shielded metal arc welding, or non-consumable, such as in gas tungsten arc welding. For a direct current system, the weld rod or stick may be a cathode for a filling type weld or an anode for other welding processes. For an alternating current arc welder, the welding electrode would not be considered an anode or cathode.

Alternating current electrodes

[edit]For electrical systems which use alternating current, the electrodes are the connections from the circuitry to the object to be acted upon by the electric current but are not designated anode or cathode because the direction of flow of the electrons changes periodically, usually many times per second.

Chemically modified electrodes

[edit]Chemically modified electrodes are electrodes that have their surfaces chemically modified to change the electrode's physical, chemical, electrochemical, optical, electrical, and transportive properties. These electrodes are used for advanced purposes in research and investigation.[39]

Uses

[edit]Electrodes are used to provide current through nonmetal objects to alter them in numerous ways and to measure conductivity for numerous purposes. Examples include:

- Electrodes for fuel cells

- Electrodes for medical purposes, such as EEG (for recording brain activity), ECG (recording heart beats), ECT (electrical brain stimulation), defibrillator (recording and delivering cardiac stimulation)

- Electrodes for electrophysiology techniques in biomedical research

- Electrodes for execution by the electric chair

- Electrodes for electroplating

- Electrodes for arc welding

- Electrodes for cathodic protection

- Electrodes for grounding

- Electrodes for chemical analysis using electrochemical methods

- Nanoelectrodes for high-precision measurements in nanoelectrochemistry

- Inert electrodes for electrolysis (made of platinum)

- Membrane electrode assembly

- Electrodes for Taser electroshock weapon

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Whitaker, Harry (2007). Brain, Mind and Medicine: Essays in eighteenth-century neuroscience. New York, NY: Springer. p. 140. ISBN 978-0387709673.

- ^ Bellis, Mary. Biography of Alessandro Volta – Stored Electricity and the First Battery.

- ^ Ross, S. (30 November 1961). "Faraday consults the scholars: the origins of the terms of electrochemistry". Notes and Records of the Royal Society of London. 16 (2): 187–220. doi:10.1098/rsnr.1961.0038. S2CID 145600326.

- ^ Conventional Current Flow and Electron Flow. (2021, September 12). Mohawk Valley Community College. https://eng.libretexts.org/@go/page/25106

- ^ "The 4 Types of Rechargeable Batteries Explained". RB Battery. 2 June 2020.

- ^ "Electron Transfer Reactions in Chemistry: Theory and Experiment". Nobelstiftung. 8 December 1992. Retrieved 2 April 2007.

- ^ Gold, Victor, ed. (2019). "The IUPAC Compendium of Chemical Terminology". doi:10.1351/goldbook.

- ^ "Marcus Theory for Electron Transfer". 12 December 2020. Retrieved 24 January 2021.

- ^ Newton, Marshall D. (1991). "Quantum chemical probes of electron-transfer kinetics: The nature of donor-acceptor interactions". Chemical Reviews. 91 (5): 767–792. doi:10.1021/cr00005a007.

- ^ Marcus, Rudolph A. (1993). "Electron transfer reactions in chemistry. Theory and experiment". Reviews of Modern Physics. 65 (3): 599–610. Bibcode:1993RvMP...65..599M. doi:10.1103/RevModPhys.65.599.

- ^ DeVault, D. (1984) Quantum Mechanical Tunneling in Biological Systems; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge.

- ^ Engineering360. "Electrodes and Electrode Materials Selection Guide: Types, Features, Applications". www.globalspec.com.

- ^ "Online Materials Information Resource". www.matweb.com.

- ^ Hawley, W. Blake; Li, Jianlin (2019). "Electrode manufacturing for lithium-ion batteries—Analysis of current and next generation processing". Journal of Energy Storage. 25: 100862. doi:10.1016/j.est.2019.100862. OSTI 1546514. S2CID 201301519.

- ^ a b Konda, Kumari; Moodakare, Sahana B.; Kumar, P. Logesh; Battabyal, Manjusha; Seth, Jyoti R.; Juvekar, Vinay A.; Gopalan, Raghavan (2020). "Comprehensive effort on electrode slurry preparation for better electrochemical performance of LiFePO4 battery". Journal of Power Sources. 480: 228837. Bibcode:2020JPS...48028837K. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2020.228837. S2CID 224980374.

- ^ Qi, Zhaoxiang; Koenig, Gary M. (2017-05-12). "Review Article: Flow battery systems with solid electroactive materials". Journal of Vacuum Science & Technology B. 35 (4): 040801. Bibcode:2017JVSTB..35d0801Q. doi:10.1116/1.4983210. ISSN 2166-2746.

- ^ Lewis, Gilbert N.; Keyes, Frederick G. (1913). "The Potential of the Lithium Electrode". Journal of the American Chemical Society. 35 (4): 340–344. doi:10.1021/ja02193a004.

- ^ a b c Kam, Kinson C.; Doeff, Marca M., "Electrode Materials for Lithium Ion Batteries", Sigma-Aldrich Technical Documents: Lab & Production Materials

- ^ Guo, Mingyi; Cao, Zengqiang; Liu, Yukang; Ni, Yuxiang; Chen, Xianchun; Terrones, Mauricio; Wang, Yanqing (May 2023). "Preparation of Tough, Binder‐Free, and Self‐Supporting LiFePO 4 Cathode by Using Mono‐Dispersed Ultra‐Long Single‐Walled Carbon Nanotubes for High‐Rate Performance Li‐Ion Battery". Advanced Science. 10 (13). doi:10.1002/advs.202207355. ISSN 2198-3844. PMC 10161069. PMID 36905241.

- ^ Zhang, Hao; Yang, Yang; Ren, Dongsheng; Wang, Li; He, Xiangming (2021-04-01). "Graphite as anode materials: Fundamental mechanism, recent progress and advances". Energy Storage Materials. 36: 147–170. doi:10.1016/j.ensm.2020.12.027. ISSN 2405-8297. S2CID 233072977.

- ^ Zhao, Qiang; Hao, Xiaoge; Su, Shiming; Ma, Jiabin; Hu, Yi; Liu, Yong; Kang, Feiyu; He, Yan-Bing (2019). "Expanded-graphite embedded in lithium metal as dendrite-free anode of lithium metal batteries". Journal of Materials Chemistry A. 7 (26): 15871–15879. doi:10.1039/C9TA04240G. ISSN 2050-7488. S2CID 195381622.

- ^ Zhang, Hao; Yang, Yang; Xu, Hong; Wang, Li; Lu, Xia; He, Xiangming (April 2022). "Li 4 Ti 5 O 12 spinel anode: Fundamentals and advances in rechargeable batteries". InfoMat. 4 (4). doi:10.1002/inf2.12228. ISSN 2567-3165.

- ^ a b c Zuo, Xiuxia; Zhu, Jin; Müller-Buschbaum, Peter; Cheng, Ya-Jun (2017-01-01). "Silicon based lithium-ion battery anodes: A chronicle perspective review". Nano Energy. 31: 113–143. doi:10.1016/j.nanoen.2016.11.013. ISSN 2211-2855.

- ^ Zhang, Wei-Jun (2011-01-01). "A review of the electrochemical performance of alloy anodes for lithium-ion batteries". Journal of Power Sources. 196 (1): 13–24. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2010.07.020. ISSN 0378-7753.

- ^ Liang, Bo; Liu, Yanping; Xu, Yunhua (2014-12-01). "Silicon-based materials as high capacity anodes for next generation lithium ion batteries". Journal of Power Sources. 267: 469–490. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2014.05.096. ISSN 0378-7753.

- ^ Li, Xiaolin; Gu, Meng; Hu, Shenyang; Kennard, Rhiannon; Yan, Pengfei; Chen, Xilin; Wang, Chongmin; Sailor, Michael J.; Zhang, Ji-Guang; Liu, Jun (2014-07-08). "Mesoporous silicon sponge as an anti-pulverization structure for high-performance lithium-ion battery anodes". Nature Communications. 5 (1): 4105. doi:10.1038/ncomms5105. ISSN 2041-1723. PMID 25001098.

- ^ Zhang, Huigang; Braun, Paul V. (2012-06-13). "Three-Dimensional Metal Scaffold Supported Bicontinuous Silicon Battery Anodes". Nano Letters. 12 (6): 2778–2783. doi:10.1021/nl204551m. ISSN 1530-6984. PMID 22582709.

- ^ Ohnsman, Alan. "Ex-Tesla Engineer Building Silicon Anode Plant As U.S. Amps Up EV Battery Production". Forbes. Retrieved 2022-11-19.

- ^ a b Alex Scott (April 7, 2019). "In the battery materials world, the anode's time has come". cen.acs.org. Retrieved 2022-11-19.

- ^ Liu, Bin; Zhang, Ji-Guang; Xu, Wu (2018-05-16). "Advancing Lithium Metal Batteries". Joule. 2 (5): 833–845. doi:10.1016/j.joule.2018.03.008. ISSN 2542-4785.

- ^ a b Palacín, M. R.; de Guibert, A. (2016-02-05). "Why do batteries fail?". Science. 351 (6273): 1253292. doi:10.1126/science.1253292. hdl:10261/148077. ISSN 0036-8075. PMID 26912708. S2CID 11534630.

- ^ Li, Dawei; Wang, Yikai; Hu, Jiazhi; Lu, Bo; Cheng, Yang-Tse; Zhang, Junqian (2017-10-31). "In situ measurement of mechanical property and stress evolution in a composite silicon electrode". Journal of Power Sources. 366: 80–85. Bibcode:2017JPS...366...80L. doi:10.1016/j.jpowsour.2017.09.004. ISSN 0378-7753.

- ^ a b Xu, Rong; Zhao, Kejie (2016-12-12). "Electrochemomechanics of Electrodes in Li-Ion Batteries: A Review". Journal of Electrochemical Energy Conversion and Storage. 13 (3). doi:10.1115/1.4035310. ISSN 2381-6872.

- ^ de Vasconcelos, Luize Scalco; Xu, Rong; Zhao, Kejie (2017). "Operando Nanoindentation: A New Platform to Measure the Mechanical Properties of Electrodes during Electrochemical Reactions". Journal of the Electrochemical Society. 164 (14): A3840–A3847. doi:10.1149/2.1411714jes. ISSN 0013-4651. S2CID 102588028.

- ^ Zhao, Kejie; Pharr, Matt; Cai, Shengqiang; Vlassak, Joost J.; Suo, Zhigang (June 2011). "Large Plastic Deformation in High-Capacity Lithium-Ion Batteries Caused by Charge and Discharge: Large Plastic Deformation in Lithium-Ion Batteries". Journal of the American Ceramic Society. 94: s226–s235. doi:10.1111/j.1551-2916.2011.04432.x.

- ^ Spaepen *, F. (2005-09-11). "A survey of energies in materials science". Philosophical Magazine. 85 (26–27): 2979–2987. Bibcode:2005PMag...85.2979S. doi:10.1080/14786430500155080. ISSN 1478-6435. S2CID 220330377.

- ^ Larché, F; Cahn, J. W (1973-08-01). "A linear theory of thermochemical equilibrium of solids under stress". Acta Metallurgica. 21 (8): 1051–1063. doi:10.1016/0001-6160(73)90021-7. ISSN 0001-6160.

- ^ Zhao, Kejie; Cui, Yi (2016-12-01). "Understanding the role of mechanics in energy materials: A perspective". Extreme Mechanics Letters. Mechanics of Energy Materials. 9: 347–352. doi:10.1016/j.eml.2016.10.003. ISSN 2352-4316.

- ^ Durst, R., Baumner, A., Murray, R., Buck, R., & Andrieux, C., "Chemically modified electrodes: Recommended terminology and definitions (PDF) Archived 2014-02-01 at the Wayback Machine", IUPAC, 1997, pp 1317–1323.

Further reading

[edit]- Kebede, Mesfin A.; Ezema, Fabian I., eds. (2022). Electrode materials for energy storage and conversion (First ed.). Boca Raton: CRC Press/Taylor & Francis. doi:10.1201/9781003145585. ISBN 978-0-367-70304-2. S2CID 240536462.

- Doeff, MM; Chen, G; Cabana, J; Richardson, TJ; Mehta, A; Shirpour, M; Duncan, H; Kim, C; Kam, KC; Conry, T (11 November 2013). "Characterization of electrode materials for lithium ion and sodium ion batteries using synchrotron radiation techniques". Journal of Visualized Experiments (81): e50594. doi:10.3791/50594. PMC 3989498. PMID 24300777.

![{\displaystyle k=A\,\exp \left[{\frac {-(\Delta G^{0}+\lambda )^{2}}{4\lambda kT}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/d5dce1cabe338c7c99de9017275f3f525aecd1f5)

![{\displaystyle w_{ET}={\frac {|J|^{2}}{\hbar }}{\sqrt {\frac {\pi }{\lambda kT}}}\exp \left[{\frac {-(\Delta E+\lambda )^{2}}{4\lambda kT}}\right]}](https://wikimedia.org/api/rest_v1/media/math/render/svg/3a9ac3bceea415577318ca69fea5d6a3073d9f81)