Beta-adrenergic agonist

| Beta adrenergic receptor agonists | |

|---|---|

| Drug class | |

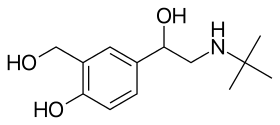

Skeletal structure formula of salbutamol (albuterol) — a widely used medication to treat asthma attacks | |

| Class identifiers | |

| Use | Bradycardia, Asthma, heart failure, etc. |

| ATC code | R03 |

| Biological target | Adrenergic receptors (β subtype) |

| External links | |

| MeSH | D000318 |

| Legal status | |

| In Wikidata | |

Beta adrenergic agonists or beta agonists are medications that relax muscles of the airways, causing widening of the airways and resulting in easier breathing.[1] They are a class of sympathomimetic agents, each acting upon the beta adrenoceptors.[2] In general, pure beta-adrenergic agonists have the opposite function of beta blockers: beta-adrenoreceptor agonist ligands mimic the actions of both epinephrine- and norepinephrine- signaling, in the heart and lungs, and in smooth muscle tissue; epinephrine expresses the higher affinity. The activation of β1, β2 and β3 activates the enzyme, adenylate cyclase. This, in turn, leads to the activation of the secondary messenger cyclic adenosine monophosphate (cAMP); cAMP then activates protein kinase A (PKA) which phosphorylates target proteins, ultimately inducing smooth muscle relaxation and contraction of the cardiac tissue.[3]

Function

[edit]

Activation of β1 receptors induces positive inotropic, chronotropic output of the cardiac muscle, leading to increased heart rate and blood pressure, secretion of ghrelin from the stomach, and renin release from the kidneys.[4]

Activation of β2 receptors induces smooth muscle relaxation in the lungs, gastrointestinal tract, uterus, and various blood vessels. Increased heart rate and heart muscle contraction are associated with the β1 receptors; however, β2 cause vasodilation in the myocardium.[citation needed]

β3 receptors are mainly located in adipose tissue.[5] Activation of the β3 receptors induces the metabolism of lipids.[6]

Medical uses

[edit]Indications of administration for β agonists include:

- Bradycardia (slow heart rate)

- Asthma

- Chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD)

- Heart failure

- Allergic reactions

- Hyperkalemia

- Beta blocker poisoning

- Premature labor (this is an off-label use and could be detrimental)[7]

Side effects

[edit]Although minor compared to those of epinephrine, beta agonists usually have mild to moderate adverse effects, which include anxiety, hypertension, increased heart rate, and insomnia. Other side effects include headaches and essential tremor. Hypoglycemia was also reported due to increased secretion of insulin in the body from activation of β2 receptors.[citation needed]

In 2013, zilpaterol, a β agonist sold by Merck, was temporarily withdrawn due to signs of sickness in some cattle that were fed the drug.[8]

Receptor selectivity

[edit]Most agonists of the beta receptors are selective for one or more beta-adrenoreceptors. For example, patients with low heart rate are given beta agonist treatments that are more "cardio-selective" such as dobutamine, which increases the force of contraction of the heart muscle. Patients who are suffering from chronic inflammatory lung diseases such as asthma or COPD may be treated with medication targeted to induce more smooth muscle relaxation in the lungs and less contraction of the heart, including first-generation drugs like salbutamol (albuterol) and later-generation medications in the same class.[9]

β3 agonists are currently under clinical research and are thought to increase the breakdown of lipids in obese patients.[10]

β1 agonists

[edit]β1 agonists stimulate adenylyl cyclase activity and opening of calcium channel (cardiac stimulants; used to treat cardiogenic shock, acute heart failure, bradyarrhythmias). Selected examples are:

- Denopamine

- Dobutamine

- Dopexamine (β1 and β2)

- Epinephrine (non-selective)

- Isoprenaline (INN), isoproterenol (USAN) (β1 and β2)

- Prenalterol

- Xamoterol

β2 agonists

[edit]β2 agonists stimulate adenylyl cyclase activity and closing of calcium channel (smooth muscle relaxants; used to treat asthma and COPD). Selected examples are:

- Arformoterol

- Buphenine

- Clenbuterol

- Dopexamine (β1 and β2)

- Epinephrine (non-selective)

- Fenoterol

- Formoterol

- Isoetarine

- Isoprenaline (INN), isoproterenol (USAN) (β1 and β2)

- Levosalbutamol (INN), levalbuterol (USAN)

- Orciprenaline (INN), metaproterenol (USAN)

- Pirbuterol

- Procaterol

- Ritodrine

- Salbutamol (INN), albuterol (USAN)

- Salmeterol

- Terbutaline

β3 agonists

[edit]Undetermined/unsorted

[edit]These agents are also listed as agonists by MeSH.[11]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ "WHAT ARE BETA-AGONISTS?". Thoracic.org. American Thoracic Society. Archived from the original on 13 June 2010. Retrieved 17 October 2014.

- ^ Adrenergic+beta-Agonists at the U.S. National Library of Medicine Medical Subject Headings (MeSH)

- ^ Wallukat G (November 2002). "The beta-adrenergic receptors". Herz. 27 (7): 683–690. PMID 12439640.

- ^ Yoo B, Lemaire A, Mangmool S, Wolf MJ, Curcio A, Mao L, et al. (October 2009). "Beta1-adrenergic receptors stimulate cardiac contractility and CaMKII activation in vivo and enhance cardiac dysfunction following myocardial infarction". American Journal of Physiology. Heart and Circulatory Physiology. 297 (4): H1377–H1386. PMID 19633206.

- ^ Johnson M (January 2006). "Molecular mechanisms of beta(2)-adrenergic receptor function, response, and regulation". The Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology. 117 (1): 18–24, quiz 25. PMID 16387578.

- ^ Lowell BB, Flier JS (1997). "Brown adipose tissue, beta 3-adrenergic receptors, and obesity". Annual Review of Medicine. 48: 307–316. PMID 9046964.

- ^ "FDA Drug Safety Communication: New warnings against use of terbutaline to treat preterm labor". FDA. 18 June 2019.

- ^ "Exclusive: FDA says working with Merck, USDA on cattle drug Zilmax - Yahoo! News". Archived from the original on 2013-08-27. Retrieved 2013-08-16.

- ^ Pias MT. "The Pharmacology of Adrenergic Receptors". Archived from the original on 12 March 2016.

- ^ Meyers DS, Skwish S, Dickinson KE, Kienzle B, Arbeeny CM (February 1997). "Beta 3-adrenergic receptor-mediated lipolysis and oxygen consumption in brown adipocytes from cynomolgus monkeys". The Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism. 82 (2): 395–401. PMID 9024225.

- ^ MeSH list of agents 82000318

External links

[edit] Media related to Beta-adrenergic agonists at Wikimedia Commons

Media related to Beta-adrenergic agonists at Wikimedia Commons