Black Brunswickers

| Herzoglich Braunschweigisches Feldcorps | |

|---|---|

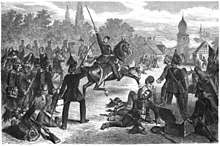

The Brunswick Ducal Corps at the Battle of Halberstadt led by the Black Duke | |

| Active | 1809-1820s |

| Nickname(s) | Schwarze Schar (Black Troop/Horde/Host) Schwarze Legion (Black Legion) Black Brunswickers |

| Motto(s) | Sieg oder Tod! (Victory or Death!) |

| March | Marsch Herzog von Braunschweig |

| Engagements | Battle of Halberstadt Battle of Olper Battle of Quatre Bras Battle of Waterloo |

The Brunswick Ducal Field-Corps (German: Herzoglich Braunschweigisches Feldkorps), commonly known as the Black Brunswickers in English and the Schwarze Schar (Black Troop, Black Horde, or Black Host) or Schwarze Legion (Black Legion) in German, were a military unit in the Napoleonic Wars. The corps was raised from volunteers by German-born Frederick William, Duke of Brunswick-Wolfenbüttel (1771–1815). The Duke was a harsh opponent of Napoleon Bonaparte's occupation of his native Germany.[1] Formed in 1809 when war broke out between the First French Empire and the Austrian Empire, the corps initially comprised a mixed force, around 2,300 strong, of infantry, cavalry and later supporting artillery.[1][2][3]

Most units of the corps wore black uniforms, leading to the "black" nicknames of the unit, though some light units (such as sharpshooters and uhlans) wore green uniforms. The Brunswickers wore silvered skull "totenkopf" badges on their hats. Their title originated from Duke Frederick William, who claimed the Duchy of Brunswick-Lüneburg, which the French had abolished in order to incorporate its lands into the French satellite Kingdom of Westphalia. The Black Brunswickers earned themselves a fearsome reputation over the following decade, taking part in several significant battles including the prelude to the Battle of Waterloo, at Quatre Bras on 16 June 1815, where the Duke lost his life. However, recruiting, the replacement of casualties, and finance had always been problematic, and the corps was disbanded in the early 1820s.

The exploits of the Brunswickers caught the British Victorian public's imagination: an example of this can be found in John Everett Millais's painting The Black Brunswicker. Completed in 1860, the painting depicts a Brunswicker in his black uniform bidding goodbye to an unnamed woman.

Formation and early years[edit]

War of the Fifth Coalition[edit]

In 1806 the Duke of Brunswick-Lüneburg, Charles William Ferdinand, was fatally wounded during the Prussian defeat at the Battle of Jena–Auerstedt. Following Prussia's defeat and the collapse of the Fourth Coalition against Napoleon, his duchy remained under French control. Rather than permit the Duke's heir, Frederick William, to succeed to his father's title, Napoleon seized the duchy and, in 1807, incorporated it into his newly created model Kingdom of Westphalia ruled by his brother Jérôme. Two years later in 1809 the Fifth Coalition against Napoleon was formed between the Austrian Empire and the United Kingdom. The dispossessed Frederick William, who had been a strenuous critic of French domination in Germany, seized this opportunity to seek Austrian help to raise an armed force. To finance this venture he mortgaged his principality in Oels. In its initial incarnation (dated to 25 July 1809), the 2300-strong 'free' corps consisted of two battalions of infantry, one Jäger battalion, a company of sharpshooters, and a mixed cavalry contingent including hussars and uhlans.[1][4]

Despite a successful campaign with their Austrian allies, the defeat of the latter at the Battle of Wagram on 6 July 1809 led to the Armistice of Znaim on 12 July. William refused to accept this and led his Schwarze Schar ("Black Host") into Germany, succeeding in briefly taking control of the city of Brunswick. Faced with superior Westphalian forces, the Brunswickers conducted a remarkable fighting retreat across Germany, twice holding off the pursuing armies, at the Battle of Halberstadt and the Battle of Ölper; finally being evacuated by the Royal Navy from the mouth of the river Weser. Landing in England, the Duke was welcomed by his cousin and brother-in-law, the Prince Regent (later King George IV) and the Black Brunswickers entered British service.[5] During the next few years, the Brunswickers earned themselves a sound reputation through service with the British in the Peninsular Campaign. However, steady attrition in battles and skirmishes through Portugal and Spain, combined with a lack of political support and financial difficulties, led to a situation where the unit's imminent disbandment looked likely.[6]

Peninsular War[edit]

When organized for British service, the corps was renamed the Brunswick Oels Jäger and Brunswick Oels Hussar regiments. Prussians represented a large part of the original officer corps, while the enlisted men were motivated by German patriotism. However, once the Oels entered English service, they were cut off from their natural recruiting grounds. Compelled to enlist men from the prisoner of war camps to fill up the ranks, the quality of soldiers in the Oels decreased. Also, the King's German Legion obtained the best of the German recruits, leaving the Oels with the less desirable ones. In addition to Germans, the Oels recruited Poles, Swiss, Danes, Dutch, and Croats. Charles Oman, the Peninsular War historian, calls the Oels a "motley crew, much given to desertion" and records one occasion where ten men were caught deserting in a body. Of these, four were shot and the rest flogged.[7]

Nevertheless, the Brunswick Oels Jägers gave a good account of themselves during the war. The regiment — really a single battalion—arrived in Portugal in early 1811. The Duke of Wellington distributed one company to the 4th Division and two companies to the 5th Division as skirmishers, while the remaining nine companies served in the newly formed 7th Division. The Oels remained in this organization until the end of the war in April 1814.[8] During this period, the Oels served in most of the major battles including Fuentes de Oñoro, Salamanca, Vitoria, the Pyrenees, Nivelle, the Nive, and Orthez.[9]

Waterloo campaign[edit]

Following Napoleon's failed invasion of Russia in 1812, and his subsequent retreat back into France, William was able to return to Brunswick in 1813 to reclaim his title. He also took the opportunity to replenish the ranks of his Black Brunswickers. Upon Napoleon's escape from Elba in 1815 he once more placed himself under the Duke of Wellington's command and joined the allied forces of the Seventh Coalition in Belgium. The "Brunswick Corps", as it is called in the order of battle for the Waterloo campaign, formed up as a discrete division in the allied reserve. Its strength is given as 5,376 men, composed of eight infantry battalions: one advance guard or Avantgarde, one life guard or Leib-Bataillon, three light and three line battalions. They were supported by both a horse and foot artillery battery of eight guns each. Also included were a regiment of Brunswicker hussars while a single squadron of uhlans were often attached to the allied cavalry corps.[10]

Battle of Quatre Bras[edit]

Quatre Bras was a hamlet at a strategic crossroads on the road to Brussels. French control of it would not only threaten the city, but divide Wellington's allied army from Blucher's Prussians. At 14:00 on 16 June 1815, after some initial skirmishing, the main French force under Marshal Ney, approached Quatre Bras from the south. They came up against the 2nd Netherlands Division who had formed a line well in advance of the crossroads. Facing three French infantry divisions and a cavalry brigade, the Dutch and Nassau troops were forced back but did not break. Reinforcements arrived at 15:00, being a Dutch cavalry brigade, Picton's 5th British Division, followed closely by the Brunswick Corps. The sharpshooters of the Brunswick Advance Guard regiment were sent to support Dutch skirmishers in Bossou Wood on the allied right (western) flank; the rest of the corps took up a reserve position across the Brussels road.[11] The Duke reassured his inexperienced troops by walking up and down in front of them, calmly puffing on his pipe.[12]

A French infantry attack was halted by the allied front line, which was attacked in turn by French cavalry. Wellington moved the Brunswick infantry into the front line, where they were subjected to intense French artillery fire, forcing them to fall back a short distance. As a mass of French infantry advanced up the main road, the Duke led a charge by his uhlans, but they were beaten back. Swept by canister shot at short range, the Brunswickers broke and rallied at the crossroads itself. At this point, the Duke, who was reforming his troops, was hit by a musket ball, which passed through his hand and into his liver. He was rescued by the men of the Leib Regiment, who carried him back using their muskets as a stretcher. He died shortly afterwards. The Duke's final words, to his aide Major von Wachholtz, were:

Mein lieber Wachholtz, wo ist denn Olfermann? (My dear Wachholtz, where is Olfermann?)[13]

Colonel Elias Olfermann was the Duke's adjutant general, who assumed immediate command of the corps.[14] Wellington then ordered the Brunswick hussars to make an unsupported counterattack on the French light cavalry brigade, but they were driven off by heavy fire. Later in the battle, French cuirassiers broke the allied front line and were only prevented from taking the crossroads by the Brunswick infantry who had formed themselves into squares. By 21:00, allied reinforcements, including the newly arrived Brunswick 1st and 3rd light regiments, had driven the French back to their starting positions.[15] Brunswick losses that day amounted to 188 killed and 396 wounded.[16]

Battle of Waterloo[edit]

Only two days later, on Sunday 18 June, the Duke of Wellington positioned his Anglo-allied army along a ridge near the village of Waterloo, in order to block Napoleon's advance along the road to Brussels. The Brunswick Corps formed part of Wellington's reserve corps, under his personal command.[17] In that capacity, they were kept well behind the crest of the ridge and avoided casualties during the opening French bombardment. In the early part of the afternoon, the British Foot Guards moved down the slope to reinforce the Château d'Hougoumont, which was under fierce French attack; the Brunswick Corps was brought forward to take their place.

At about 16:00, Ney decided to attempt to break the centre right of the Anglo-allied line with his cavalry. Some 4,800 French horsemen charged up the hill and into the allied infantry, who had formed themselves into squares to resist them. In all, 9,000 cavalry were involved in repeated attacks on the allied squares but were unable to break any of them, including the Brunswickers, who some British officers regarded as "shaky".[18] The Brunswick hussars and uhlans, who formed part of the 7th British Cavalry Brigade, made harrying attacks on the French whenever they retired to regroup. Eventually, Ney had no choice but to abandon the attacks.

The French capture of the fortified farm of La Haye Sainte had left a gap in the centre of Wellington’s line, and the Brunswick infantry were brought along to fill it. It was here that Napoleon sent one of two attacks by his imperial guard in a last effort to break Wellington’s army. Faced with the veterans of the grenadiers of the middle guard, the inexperienced Brunswickers broke from the line and "fell back in disorder", but rallied when they reached the cavalry reserve in the rear. The same fate befell the Nassau Infantry Regiment and two British battalions. Finally, the guards were halted and thrown back when they were surprised by a flank attack from allied troops.[19][unreliable source] The Brunswick Corps had recovered sufficiently to participate in the allied “general advance” that swept the French army from the field. British sources give the number of Brunswickers killed in action that day as 154 with 456 wounded and 50 missing.[20]

In the following days, they escorted 2,000 French prisoners back to Brussels and then marched on to Paris. They finally returned to Brunswick on 6 December 1815.[21]

Uniform[edit]

The Brunswickers were awarded various nicknames by their contemporaries, including the Black Crows, the Black Legion and the Black Horde. However, although the uniforms of the individual units that comprised the corps were, as the names suggest, predominantly black, they varied in their details.

- Infantry units in 1809 wore a black polrock or "Polish coat", a type of frock coat derived from a Lithuanian garment called a litewka which had six pairs of black lace fastenings down the front. Trousers were black with a side stripe of light blue. A tall collar and shoulder straps also in the regimental colour. The backpack and other equipment were of Austrian design and manufacture.[22] The Sharpshooter companies wore a dark green Prussian-style coatee and a tall hat of Austrian origin with an elongated brim turned-up at one side.[23] In the Peninsular War, the polrock was replaced by a short black koller or cavalry-style tunic. Equipment and badges of rank were of British pattern. Trousers were black with a side stripe of light blue; footwear was black shoes with buttoned gaiters. They wore a shako on their heads, with a death's head badge for the Leib battalion or a hunting horn badge for light infantry. The hussar cavalry were garbed in a black, light blue collared dolman, sometimes with a black pelisse. Black overalls were worn over tight breeches of the hussar style. The hussars also wore a black Shako. The sword and equipment were originally of Austrian design.[24] The Uhlan squadron wore a green kurtka or lancer's jacket with red facings and a traditional czapka cap, their uniform being a copy of the Austrian Graf von Meerveldt Uhlan Regiment. The lance had a red and yellow pennon.[25] By 1815, the Uhlans were wearing all-black uniforms, the czapka was now topped light blue and piped and crossed on top in yellow.[26] For the 1815 Waterloo Campaign, three new line battalions and three new light battalions were added to the ducal forces. These units wore the black koller, with black trousers with a side stripe in each regiment's facing colour; footwear was black shoes with buttoned gaiters. They wore a shako on their heads, with white metal "amazon" style plates for the line battalions or a white metal hunting horn badge for light infantry. The line battalions wore a short light blue over yellow "carrot" pompom; that of the light battalions was yellow over light blue and the Leib Battalion continued to wear the falling black horsehair plume and the death's head badge. Artillerymen wore similar clothing to the cavalry: mostly black in colour with a koller and black trousers. They were additionally equipped with a standard hussar sword should they have need to defend their guns.[27]

There are a number of speculative theories on the origin of the Brunswickers' dark and seemingly grim choice of garb. It has been suggested that black was chosen to mourn Duke Frederick William's late father; as a sign of respect for the Duke; or in mourning for the Duke's occupied homeland.[28] Colonel Augustus Frazer, who had served alongside the Brunswickers, reported that black was adopted in mourning for the Duke's wife, Princess Marie of Baden, who had died in 1808, and that the black uniforms would not be put aside until Brunswick had been finally liberated.[29]

The black clothing of the Brunswicker soldier became closely associated across Germany with the liberation movement of 1813. Accordingly even after Brunswick became a member of the North German Confederation in 1866 and the German Empire in 1871 the military units of the Dukedom retained the special privilege of wearing uniforms in black, in marked contrast to the Prussian blue of most of the other member states. This distinction lasted until April 1892 when a new military convention between Brunswick and Prussia did away with the special status and uniforms of the Brunswick regiments.[30]

Inspired art[edit]

The Black Brunswicker (1860), by John Everett Millais was inspired in part by the exploits of the Brunswickers[2] and in part by the contrasts of black broadcloth and pearl-white satin in a moment of tender conflict.[31]

The artwork took an estimated three months to paint, and it was greatly admired at the time. It was also bought for the highest price Millais had received from dealer and publisher Ernest Gambart - the lucrative sum of 100 guineas.[2] Later, in 1898, William Hesketh Lever purchased the work for his private collection.[2] Charles Dickens' daughter Kate was used as a model for the woman seen in the painting.[2]

Later years[edit]

A single infantry regiment and the hussars were maintained by the Duchy of Brunswick after the end of the Napoleonic War. In 1830, the uniform colour was changed to blue, but reverted to black in 1850.[32] The Brunswick units were integrated into the Prussian Army in 1866 with the titles: Braunschweigisches Infanterie-Regiment Nr.92 and Braunschweigisches Husaren Regiment Nr.17 following the Prussian regimental numbering sequence. Both units kept the skulls with the crossed bones on their helmets and caps and carried the battle honours "Peninsula-Sicily-Waterloo" until the end of World War I in 1918, when they were disbanded.[33] At that time, a collection of artefacts and uniforms from the Napoleonic era were presented by the officers of the corps to the Braunschweigisches Landesmuseum, where they remain.[34]

The historic black of the Brunswick Corps was retained by the Husaren Regiment Nr.17 in full dress parade uniform until the outbreak of war in August 1914. The Brunswick Infanterie-Regiment Nr.92 however adopted the dark blue tunic of the Prussian line infantry.[35]

Sources[edit]

- ^ a b c "Osprey Publishing". Archived from the original on 27 September 2007. Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ^ a b c d e "Lady Lever Art Gallery - artwork of the month". Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ^ "Infoplease.com". Retrieved 7 April 2007.

- ^ von Kortzfleisch, Gustav (1999) [1894]. Des Herzogs Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig Zug durch Norddeutschland im Jahre 1809. Berlin: Biblio-Verlag. ISBN 978-3-7648-1216-4.

- ^ Haythornthwaite, Philip J (1990), The Napoleonic Source Book, Guild Publishing, ISBN 978-1854092878 (p. 147)

- ^ von Pivka, Otto (1992). Napoleon's German Allies: Vol 1 (Men-at-arms). Osprey. pp. 48. ISBN 978-0-85045-211-2.

- ^ Oman, Charles (1993). Wellington's Army 1809-1814. Stackpole Books. p. 225. ISBN 0-947898-41-7.

- ^ Oman, Charles (1993). Wellington's Army 1809-1814. Stackpole Books. pp. 351–372. ISBN 0-947898-41-7.

- ^ Glover, Michael (1974). The Peninsular War 1807-1814. Penguin Books. pp. 378–386.

- ^ "Allied order of battle: Wellington's Army (1815)". Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ^ Battle of Quatre Bras: Allies' reinforcements

- ^ Von Pivka 1973 (p.23)

- ^ von Pivka, O. p.23

- ^ Anglo-Allied Army in Flanders and France - 1815: Changes in Command and Organization

- ^ Battle of Quatre Bras: Wellington's offensive

- ^ Von Pivka 1973 (p.24)

- ^ McGuigan, Ron. "Anglo-Allied Army in Flanders and France - 1815". The Napoleon Series. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ Wootten, Geoffrey (1992). Waterloo 1815: The Birth of Modern Europe. Osprey Publishing. p. 76. ISBN 1-85532-210-2.

- ^ "Napoleon's Guard at Waterloo 1815 : Maps : Pictures : Merde : Garde Recule". Napoleon, His Army and Enemies. Retrieved 17 May 2017.

- ^ Von Pivka 1973, p. 29.

- ^ The Black Brunswickers, Ludwig Baer Archived April 27, 2013, at archive.today

- ^ Von Pivka, p.33

- ^ Von Pivka, p.34

- ^ Von Pivka, p.36

- ^ Von Pivka, p.35

- ^ Philip Haythornthwaite, Uniforms Of Waterloo In Colour, Blandford Press Ltd, Poole, 1974, ISBN 0-7137-0714-3 (p. 125)

- ^ Spehr, Louis Ferdinand (1861). Friedrich Wilhelm, Herzog von Braunschweig-Lüneburg-Oels. Braunschweig: Meyer.

- ^ Scott, Walter (2007) [1816]. Paul's Letters to His Kinsfolk. unknown. p. 524. ISBN 978-0-548-08572-1.

- ^ Kershaw, Robert (2014). 24 Hours at Waterloo: 18 June 1815. WH Allen. p. 41. ISBN 978-0-753-54144-9.

- ^ Herr, Ulrich. The German Artillery from 1871 to 1914. p. 192. ISBN 978-3-902526-80-9.

- ^ "The Royal Academy and Other Exhibitions". Blackwood's Edinburgh Magazine 88.537 (Excerpt, pp79-84). July 1860. Archived from the original on 2006-09-08. Retrieved 2007-09-19.

- ^ Prebben Kannik, Military Uniforms in Colour, Blandford Press 1968 ISBN 0-7137-0482-9 (p.224)

- ^ Wilson History & Research Centre: The Black Brunswickers by Ludwig Baer Archived April 27, 2013, at archive.today

- ^ Von Pivka (1973) p.9

- ^ Verlag Starnberg, "Die Uniformen der Deutschen Armee", ISBN 3-88706-249-3

See also[edit]

- The Sacred Band (1821) set up by Alexander Ypsilantis had uniforms inspired by the Black Brunswickers

Further reading[edit]

- Hugo von Franckenberg-Ludwigsdorff: Erinnerungen an das Schwarze Corps, welches Herzog Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig-Oels im Jahre 1809 errichtete. Aus dem Tagebuche eines Veteranen. Schwetschke, Braunschweig 1859, digitized.

- Ruthard von Frankenberg: Im Schwarzen Korps bis Waterloo. Memoiren des Majors Erdmann von Frankenberg. edition von frankenberg, Hamburg 2015, ISBN 978-3-00-048000-3

- Gustav von Kortzfleisch: Des Herzogs Friedrich Wilhelm von Braunschweig Zug durch Norddeutschland im Jahre 1809. In: Militär-Wochenblatt. Beiheft 9/10, 1894, ZDB-ID 207819-3, p. 300–396 (Auch Sonderabdruck: Mittler, Berlin 1894, digitized).

- Fred Mentzel: Der Vertrag Herzog Friedrich Wilhelms von Braunschweig mit der britischen Regierung über die Verwendung des Schwarzen Korps (1809). In: Braunschweigisches Jahrbuch. Bd. 55, 1974, ISSN 0068-0745, p. 230–239, digitized.

- Detlef Wenzlik: Unter der Fahne des Schwarzen Herzogs 1809 (= Die Napoleonischen Kriege. Bd. 9). VRZ-Verlag Zörb, Hamburg 2002, ISBN 3-931482-87-1.

External links[edit]