Brussels–Charleroi Canal

| Brussels–Charleroi Canal | |

|---|---|

The course of the Brussels–Charleroi Canal | |

| |

| Specifications | |

| Length | 65 km (40 mi) |

| History | |

| Construction began | 1827 |

| Date completed | 1832 |

| Geography | |

| Start point | Brussels, Belgium |

| End point | Charleroi, Belgium |

| |

The Brussels–Charleroi Canal (French: Canal Bruxelles-Charleroi; Dutch: Kanaal Brussel-Charleroi), also known as the Charleroi Canal amongst other similar names, is an important canal in Belgium. The canal is quite large, with a Class IV Freycinet gauge, and its Walloon portion is 47.9 kilometres (29.8 mi) long. It runs from Charleroi (Wallonia) in the south to Brussels in the north.

The canal is part of a north–south axis of water transport in Belgium, whereby the north of France (via the Canal du Centre) including Lille and Dunkirk and important waterways in the south of Belgium including the Sambre valley and the sillon industriel are linked to the port of Antwerp in the north, via the Brussels–Scheldt Maritime Canal, which meets the Brussels–Charleroi Canal at the Sainctelette area of Brussels.

The Ronquières inclined plane is the canal's most remarkable feature and a tourist site.[1]

History

[edit]Early proposals

[edit]The idea of a waterway to serve the cities of Hainaut, linking them ultimately with Antwerp, was first put forward during the reign of Philip the Good, Duke of Burgundy (1396–1467). In 1436, an edict authorised the modification and deepening of the Senne river, though the project turned out to be more expensive than previously thought. The authorities of Mechelen, the sole city allowed to tax water transport on the Senne, protested extensively at the prospect of the construction of a parallel canal, and the project was abandoned.

During the 16th century, the prospect of a canal was renewed. In 1531, Emperor Charles V authorised the construction of a canal linking Charleroi and Willebroek, though work did not begin immediately. It was not until 1550 that Mary of Habsburg, Governor of the Netherlands, finally ordered work to begin. When work was finished in 1561, the canal linked Brussels to the Rupel river at Willebroek, though it did not continue south past Brussels.

As part of France from 1795 to 1815, proposals to build the canal were hampered by Napoleon's focus on waging expansionist wars.

Construction

[edit]During the Industrial Revolution, coal saw a tremendous rise in economic importance. The Sambre and Marne valleys are quite rich in coal, and during the reign of King William I of the Netherlands (1813–1840), concrete plans to extend the canal were at last made.

The project was undertaken by A. J. Barthélemy, member of the lower chamber of the States-General of the Netherlands and adviser to the regent in Brussels. He proposed inclined planes be used instead of locks, but his idea was ahead of its time. An inclined plane is quicker, and wastes less water, than a flight of canal locks, but is more costly to install and run. Jean-François Gendebien, a very prominent Belgian politician (although Belgium was then called the Southern Netherlands and was not independent) supported the idea, though finances had the last say in the matter, resulting in locks being chosen over inclined planes.

Today's canal is actually the fourth version. The first version, built from 1827 to 1832, has a gauge of only 70 tonnes (150,000 lb). Just over 20 years later, in 1854, work began to create a "large gauge" canal (today's medium gauge) of 300 tonnes (660,000 lb) on certain sections, which was completed in 1857. Ambitious enlargements began again with the lock at Flanders' Gate (French: Porte de Flandre, Dutch: Vlaamsepoort) in Brussels, which was expanded to a gauge of 600–800 tonnes (1,300,000–1,800,000 lb).

-

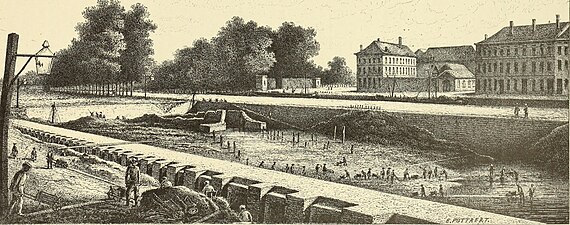

The excavations of the Brussels–Charleroi Canal near Molenbeek-Saint-Jean, c. 1830

-

General map of the canal, its waterways and railway forks (1839)

-

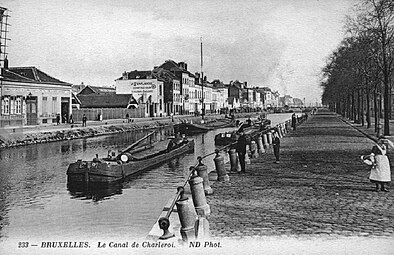

View into Brussels along the canal from Molenbeek, c. 1855

Later development

[edit]As Belgian industry began to flourish in the City of Brussels and its neighbouring municipalities, the land surrounding the canal became increasingly important and diverse. Two very prominent trade routes crossed paths in the valley of Brussels along the waterways, bringing in large numbers of merchants to lower Brussels. One of the major trade routes was from the Rhineland to Flanders, while the other one was from Antwerp to the industrial zone of Hainaut.[2] This area along the water was a booming marketplace crucial to the up-rise of urbanisation, and in turn to the modernisation of Brussels and the other cities connected by the canal.[3]

After a first period of rapid industrialisation that had taken place sometime between the 1750s and 1780s, the opening of the canal greatly increased the traffic of coal and thus the mechanisation of industry, which led to the development of foundries, engineering and metalworking companies.[4] Because of this, life around the canal expanded at very high rates. The canal was state of the art; the connection of waterways and roads allowed this area to become a centre of activity. The growth of international and domestic trade coupled with an increase in capital investment from wealthy landowners and merchants produced tons of jobs in the canal area.[3] The growth of the community continued unabated throughout the 19th century, leading to cramped living conditions near the canal.

After this, Brussels showed no signs of slowing down on its journey to becoming one of the most influential cities in all of Europe.[3] By 1930, Brussels population was up to over 200,000, compared to an estimated 65,000 in 1700.[2] During the early 1980s, the 25 neighbourhoods around the canal were home to one fifth of Brussels' population. The surrounding area holds a sense of youth, as it contributes to Brussels having the youngest population of any city in Belgium. The effects of this mass migration to the lower valley in Brussels can be seen in the diversity of cultures.[5] As the trade economy along the waterways continued to grow and attracted by the industrial opportunities, many workers moved in, first from the other Belgian provinces (mainly rural residents from Flanders)[6] and France, then from Southern European, and more recently from Eastern European and African countries. It has been estimated that the population of immigrants grew from 7% of the total population in the early 1960s to 56% of the total population in the early 2000s.[2]

By 1933, all locks downstream of Clabecq were modified to a capacity of 1,350 tonnes (2,980,000 lb). The last major improvement to the canal was the addition, in 1968, of the Class IV, 1350 tonne inclined plane at Ronquières, just uphill of Lock #5 at Ittre. The inclined plane is considered a masterpiece of civil engineering, while the lock has a rise of 13.5 m (44 ft), one of the highest in Belgium.[1]

-

Electrical traction by a trolley boat on the Charleroi Canal, c. 1899

-

Canal in Brussels, c. 1906–1908

-

Haecht Brewery along the canal in Anderlecht, 1980

Recent history

[edit]On 17 December 2005, the body of the former Rwandan cabinet minister Juvénal Uwilingiyimana was found in the canal. He had gone missing on 21 November 2005, and when his body was found, it was naked and badly decomposed.[7] Uwilingiyimana had been indicted by the International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda for his participation in the 1994 Rwandan genocide. He had been meeting with ICTR officials, and many thought he was to testify against high-ranking officials from the former Hutu regime.[7]

Ronquières inclined plane

[edit]

The Ronquières inclined plane has a length of 1,432 m (1,566 yd) and lifts boats through 68 m (223 ft) vertically.[8][9] It consists of two large caissons mounted on rails. Each caisson measures 91 m (299 ft) long by 12 m (39 ft) wide and has a water depth between 3 and 3.7 m (9.8 and 12.1 ft). It can carry one boat of 1,350 tonnes or many smaller boats within the same limits.

The weight of each caisson is held by a counterweight of 5,200 tonnes (11,500,000 lb) that runs beneath the rails.[8] Eight cables per caisson running around winches at the top allow each caisson to be moved independently of the other. They can be moved between the two canal levels at a speed of 1.3 m/s (4 ft/s), boats taking 50 minutes in total to pass through the entire structure.[8]

The inclined plane, while still in use, is now being promoted as a tourist site.[1]

Traffic

[edit]- 1987 – Tonnage: 1 094 000 T – 3084 Barges

- 1990 – Tonnage: 1 289 000 T – 3346 Barges

- 2000 – Tonnage: 2 100 000 T – 3471 Barges

- 2004 – Tonnage: 3 160 000 T – 5155 Barges

- 2005 – Tonnage: 3 019 000 T – 4812 Barges

- 2006 – Tonnage: 3 143 000 T – 5215 Barges

Gallery

[edit]-

The canal in Anderlecht

-

Canal in Anderlecht with liveaboard boats

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ a b c "Plan incliné de Ronquières" (in French). Association pour la Gestion et l'Exploitation touristiques et sportives des Voies d'Eau du Hainaut. 25 September 2007. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ a b c State, Paul, F (2015). "Historical Dictionary of Brussels". Rowman and Littlefield Publishers: 491.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - ^ a b c Polasky 1987, p. 19–23.

- ^ Charruadas 2005.

- ^ Vermeulen, Sofie (2015). The Brussels Canal Zone : Negotiating visions for urban planning. ASP. pp. 77–78.

- ^ Buron 2016, p. 80–82.

- ^ a b "Canal body 'was Rwandan minister'". BBC News. 23 December 2005. Retrieved 5 October 2007.

- ^ a b c "The inclined plane of Ronquières". Direction générale des services techniques [of Wallonia]. Archived from the original on 11 June 2008. Retrieved 6 October 2007.

- ^ Permanent International Association of Navigation Congresses. (1989). Ship lifts: report of a Study Commission within the framework of Permanent ... PIANC. ISBN 978-2-87223-006-8. Retrieved 14 December 2011.

Bibliography

[edit]- Buron, Thierry (2016). "Molenbeek, de sainte Gertrude au djihadisme". Conflits (in French). 9. Paris.

- Charruadas, Paulo (2005). "La formation de Molenbeek : industrialisation et urbanisation". Les Cahiers de la fonderie (in French). 33. Brussels.

- Polasky, Janet, L (1987). Revolution in Brussels, 1787–1793. University of New Hampshire. ISBN 978-0-87451-385-1.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link) - (in French) Sterling, A., Dambrain, M.: Le Canal de Charleroi à Bruxelles, témoin d'une tradition industrielle. Editions MET, 2001.