Marjorie Cameron

Marjorie Cameron | |

|---|---|

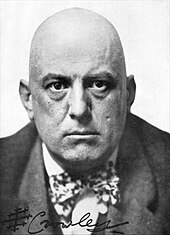

Cameron in the mid-1940s[1] | |

| Born | Marjorie Cameron April 23, 1922 Belle Plaine, Iowa, U.S. |

| Died | July 24, 1995 (aged 73) Los Angeles, California, U.S. |

| Known for | Drawing, painting, poetry |

| Movement | Beat generation, psychedelia, occultism, surrealism |

| Spouses |

|

| Children | 1 |

| Part of a series on |

| Thelema |

|---|

|

| The Rights of Man |

Marjorie Cameron Parsons Kimmel (April 23, 1922 – July 24, 1995), who professionally used the mononym Cameron, was an American artist, poet, actress and occultist. A follower of Thelema, the new religious movement established by the English occultist Aleister Crowley, she was married to rocket pioneer and fellow Thelemite Jack Parsons.

Born in Belle Plaine, Iowa, Cameron volunteered for service in the United States Navy during the Second World War, after which she settled in Pasadena, California. There she met Parsons, who believed her to be the "elemental" woman that he had invoked in the early stages of a series of sex magic rituals called the Babalon Working. They entered into a relationship and were married in 1946. Their relationship was often strained, although Parsons sparked her involvement in Thelema and occultism. After Parsons' death in an explosion at their home in 1952, Cameron came to suspect that her husband had been assassinated and began rituals to communicate with his spirit. Moving to Beaumont, she established a multi-racial occult group called The Children, which dedicated itself to sex magic rituals with the intent of producing mixed-race "moon children" who would be devoted to the god Horus. The group soon dissolved, largely because many of its members became concerned by Cameron's increasingly apocalyptic predictions.

Returning to Los Angeles, Cameron befriended the socialite Samson De Brier and established herself within the city's avant-garde artistic community. Among her friends were the filmmakers Curtis Harrington and Kenneth Anger. She appeared in two of Harrington's films, The Wormwood Star and Night Tide, as well as in Anger's film Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome. In later years, she made appearances in art-house films created by John Chamberlain and Chick Strand. Rarely remaining in one place for long, during the 1950s and 1960s she lived in Joshua Tree, San Francisco and Santa Fe. In 1955, she gave birth to a daughter, Crystal Eve Kimmel. Although intermittent health problems prevented her from working, her art and poetry resulted in several exhibitions. From the late 1970s until her death from cancer in 1995, Cameron lived in a bungalow in West Hollywood, where she raised her daughter and grandchildren, pursued her interests in esotericism, and produced artwork and poetry.

Cameron's recognition as an artist increased after her death, when her paintings made appearances in exhibitions across the U.S. As a result of increased attention on Parsons, Cameron's life also gained greater coverage in the early 2000s. In 2006, the Cameron–Parsons Foundation was created to preserve and promote her work, and in 2011 a biography of Cameron written by Spencer Kansa was published.

Biography

[edit]Early life: 1922–1945

[edit]Cameron was born in Belle Plaine, Iowa, on April 23, 1922.[2] Her father, railway worker Hill Leslie Cameron, was the adopted child of a Scots-Irish family; her mother, Carrie Cameron (née Ridenour), was of Dutch ancestry.[3] She was their first child, and was followed by three siblings: James (b. 1923), Mary (b. 1927), and Robert (b. 1929).[4] They lived on the wealthier north side of town, although life was nevertheless hard due to the Great Depression.[5] Cameron attended Whittier Elementary School and Belle Plaine High School, where she did well at art, English, and drama but failed algebra, Latin, and civics lessons. She also participated in athletics, glee club, and chorus.[6] Relating that one of her childhood friends had committed suicide and that she too had contemplated it, she characterized herself as a rebellious child, claiming that "I became the town pariah ... Nobody would let their kid near me".[7] She had sexual relationships with various men; after Cameron became pregnant, her mother performed an illegal home abortion.[8] In 1940, the Cameron family relocated to Davenport so Hill could work at the Rock Island Arsenal munitions factory. Cameron completed her final year of high school education at Davenport High School.[9] Leaving school, she worked as a display artist in a local department store.[9]

Following the United States' entry into the Second World War, Cameron signed up for the Women Accepted for Volunteer Emergency Service, a part of the United States Navy, in February 1943. Initially sent to a training camp at Iowa State Teachers College in Cedar Falls, she was subsequently posted to Washington, D.C., where she served as a cartographer for the Joint Chiefs of Staff. In the course of these duties, she met U.K. Prime Minister Winston Churchill in May 1943.[10] She was reassigned to the Naval Photographic Unit in Anacostia, where she worked as a wardrobe mistress for propaganda documentaries, and during this period met various Hollywood stars.[11] When her brother James returned to the U.S. injured from service overseas, she went AWOL and returned to Iowa to see him, as a result of which she was court–martialed and confined to barracks for the rest of the war.[12] For reasons unknown to her, she received an honorable discharge from the military in 1945. To join her family, she traveled to Pasadena, California, where her father and brothers had found work at the Jet Propulsion Laboratory (JPL).[13]

Jack Parsons: 1946–1952

[edit]

In Pasadena, Cameron ran into a former colleague, who invited her to visit the large American Craftsman-style house where he was currently lodging, 1003 Orange Grove Avenue, also known as "The Parsonage". The house was so-called because its lease was owned by Jack Parsons, a rocket scientist who had been a founding member of the Jet Propulsion Laboratory and who was also a devout follower of Thelema, a new religious movement founded by English occultist Aleister Crowley in 1904. Parsons was the head of the Agape Lodge, a branch of the Thelemite Ordo Templi Orientis (O.T.O.).[14] Unbeknownst to Cameron, Parsons had just finished a series of rituals using Enochian magic with his friend and lodger L. Ron Hubbard, all with the intent of attracting an "elemental" woman to be his lover. Upon encountering Cameron with her distinctive red hair and blue eyes, Parsons considered her to be the individual whom he had invoked.[15] After they met at The Parsonage on January 18, 1946, they were instantly attracted to each other and spent the next two weeks in Parsons' bedroom together. Although Cameron was unaware of it, Parsons saw this as a form of sex magic that constituted part of the Babalon Working, a rite to invoke the birth of Thelemite goddess Babalon onto Earth in human form.[16]

During a brief visit to New York City to see a friend, Cameron discovered that she was pregnant and decided to have an abortion.[17] Parsons meanwhile had founded a company with Hubbard and Hubbard's girlfriend Sara Northrup, Allied Enterprises, into which he invested his life savings. It became apparent that Hubbard was a confidence trickster, who tried to flee with Parsons' money, resulting in the end of their friendship.[18] Returning to Pasadena, Cameron consoled Parsons, painting a picture of Northrup with her legs severed below the knee.[19] Parsons decided to sell The Parsonage, which was then demolished for redevelopment, and the couple moved to Manhattan Beach. On October 19, 1946, he and Cameron married at the San Juan Capistrano courthouse in Orange County, in a service witnessed by his best friend Edward Forman.[20] Having an aversion to all religion, Cameron initially took no interest in Parsons' Thelemite beliefs and occult practices, although he maintained that she had an important destiny, giving her the magical name of "Candida", often shortened to "Candy", which became her nickname.[21]

In the winter of 1947, Cameron travelled from New York to Paris aboard the SS America with the intention of studying art at the Académie de la Grande Chaumière, which she hoped would admit her with a letter of recommendation from Pasadena's Art Center School. She also wanted to visit England and meet with Crowley and explain to him Parsons' Babalon Working. Cameron learned upon her arrival in Paris that Crowley had died and that she had not been admitted to the college. She found post-war Paris "extreme and bleak", befriended Juliette Gréco, and spent three weeks in Switzerland before returning home.[22] When Cameron developed catalepsy, Parsons suggested that she read Sylvan Muldoon's books on astral projection and encouraged her to read James Frazer's The Golden Bough, Heinrich Zimmer's The King and the Corpse, and Joseph Campbell's The Hero with a Thousand Faces.[23] Although she still did not accept Thelema, she became increasingly interested in the occult, and in particular the use of the tarot.[23]

Parsons' and Cameron's relationship was deteriorating and they contemplated divorce.[24] While Cameron visited the artistic commune at San Miguel de Allende in Mexico and befriended the artist Renate Druks, Parsons moved into a house in Redondo Beach and was involved in a brief relationship with an Irishwoman named Gladis Gohan before Cameron returned.[25] By March 1951, Parsons and Cameron had moved to the coach house at 1071 South Orange Grove, while he began work at the Bermite Powder Company, constructing explosives for the film industry.[26] They started holding parties once more that were attended largely by bohemians and members of the beat generation, and Cameron attended the jazz clubs of Central Avenue with her friend, the sculptor Julie Macdonald.[27] Cameron produced illustrations for fashion magazines and sold some of her paintings, including some purchased by a friend, the artist Jirayr Zorthian.[28] Parsons and Cameron had decided to travel to Mexico for a few months.[29] On the day before they planned to leave—June 17, 1952—he received a rush order of explosives for a film set, and began work on the order at his house.[30] In the midst of this project, an explosion destroyed the building, fatally wounding Parsons. He was rushed to hospital, but was declared dead.[31] Cameron did not want to see his body and retreated to San Miguel, asking her friend George Frey to oversee the cremation.[32]

The Children, Kenneth Anger, and Curtis Harrington: 1952–1968

[edit]In medical language Cameron is a lunatic. Elementals and forces and ideas like Babalon when uncontrolled are dangerous. She is now uncontrolled because Jack is dead. Her lunatic four or five fold black and white moonchild operations or attempted operations are summarised by AC's [Aleister Crowley's] comment; 'I get fairly frantic when I contemplate the idiocy of these louts.' I would insist on a vow of Holy obedience and forbid all workings. In my opinion the poor girl is too far gone now to stop. You should dissolve and excommunicate her if she does not take and keep the oath ... She will be shut up and rightly so in a lunatic asylum as soon as she comes out in the open.

– Gerald Yorke, writing to Karl Germer[33]

While in Mexico, Cameron began performing blood rituals in the hope of communicating with Parsons' spirit; during these, she cut her own wrists. As part of these rituals, she claimed to have received a new magical identity, Hilarion.[34] When she heard that an unidentified flying object had allegedly been seen over Washington D.C.'s Capitol Building, she considered it a response to Parsons' death.[34] After two months, she returned to California and attempted suicide.[35] Increasingly interested in occultism, she read through her husband's papers. Embracing his Thelemic beliefs, she came to understand his purpose in carrying out the Babalon Working and also came to believe that the spirit of Babalon had been incarnated into herself.[36] She came to believe that Parsons had been murdered by the police or anti-Zionists, and continued her attempts at astral projection to commune with his spirit.[37]

Her mental stability was deteriorating, and she became convinced that a nuclear test on Eniwetok Atoll would result in the destruction of the California coast.[38] There is inconclusive evidence that she was institutionalized in a psychiatric ward during this period, before having a brief affair with African-American jazz player Leroy Booth, a relationship that would have been illegal at the time.[39] At some point in this period, she stayed with the Thelemite Wilfred Talbot Smith and his wife,[40] although he thought that she had "bats in the belfry" and ignored what he described as her "Mad Mental Meanderings".[41]

In December 1952, Cameron moved to a derelict ranch in Beaumont, California, about 90 miles (140 km) from Redondo Beach.[42] With the aid of Druks and Paul Mathison, she gathered a loose clique of magical practitioners around herself which she called "The Children". Intentionally comprising members from various races, she oversaw a range of sex magic rituals with the intent of creating a breed of mixed-race "moonchildren" who would be devoted to Horus.[43] She became pregnant as a result of these rites, and termed her forthcoming child "the Wormwood Star", although the pregnancy ended in miscarriage.[44] Over time, many of Cameron's associates within The Children distanced themselves from her, in particular because of her increasingly apocalyptic pronouncements; she claimed that Mexico was about to conquer the U.S., that a race war was about to break out in the Old World, and that a comet would hit the Earth, and that a flying saucer would rescue her and her followers and take them to Mars.[45] During her magical rituals she used a range of drugs, including marijuana, peyote, and magic mushrooms, and in June 1953 she visited Los Angeles to attend a Gerald Heard lecture on the mind-expanding uses of hallucinogens.[46] Cameron was suffering from auditory hallucinations, frequent bouts of depression, and dramatic mood swings.[47] During this period, she corresponded with the Thelemite Jane Wolfe,[48] although other Thelemites and Crowley associates such as Karl Germer and Gerald Yorke deemed her insane.[49]

After using the Chinese divination text the I Ching, Cameron returned to Los Angeles, moving in with Booth until the duo were arrested for illegal drug possession.[51] Released on bail, she moved into Druks' Malibu home, and through her joined the avant-garde artistic circle surrounding the socialite Samson De Brier.[52] It was through this circle that Cameron met the Thelemite film maker Kenneth Anger, and after a party titled "Come As Your Madness" which was organised by Mathison and Druks, he decided to produce a film featuring Cameron and others in the group. The resulting film was Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome.[53] After seeing the film, the English Thelemite Kenneth Grant wrote to Cameron hoping that she might move to England and join his London-based group, the New Isis Lodge; Cameron never responded.[54]

Through common friends Cameron met Sheridan "Sherry" Kimmel, and the two entered a relationship. A veteran of the Second World War from Florida, Kimmel suffered from posttraumatic stress disorder, often causing him severe mood swings. He developed an interest in occultism and became intensely jealous of Parsons' continuing influence over Cameron, destroying Parsons' notes on the Babalon Working that she had kept.[55] Cameron again became pregnant, although she was unsure who the father was. She gave birth to a daughter, Crystal Eve Kimmel, on Christmas Eve 1955.[56] She allowed her daughter to behave how she pleased, believing that this was the best way for her to learn.[57] With her friend, the film-maker Curtis Harrington, Cameron then produced a short film, The Wormwood Star, which was filmed at the home of multi-millionaire art collector Edward James; the film features images of Cameron's paintings, and recitations of her poems.[58]

In autumn 1956, Cameron's first exhibition was held, at Walter Hopps's studio in Brentwood; several paintings were destroyed when the gallery caught fire.[59] Around this time, Cameron was introduced to the actor Dean Stockwell at a public recital of her poetry; he then introduced her to his friend and fellow actor Dennis Hopper.[60] She was also an associate of the artist Wallace Berman, who used a photograph of her on the front of the first volume of his art journal, Semina. The volume also included Cameron's drawing, Peyote Vision.[61] This artwork was featured in Berman's 1957 exhibition at Los Angeles' Feris Gallery, which was raided and shut down by the police. Investigating officers claimed that Peyote Vision, which featured two copulating figures, was pornographic and indecent, thus legitimising their actions.[62]

In late 1957, Cameron moved to San Francisco with her friends Norman Rose and David Metzer.[63] There she mingled within the same bohemian social circles as many of the beat generation of artists and writers, and was a regular at avant-garde poetry readings.[64] She began a relationship with the artist Burt Shonberg of Cafe Frankenstein, and with him moved into a ranch outside of Joshua Tree.[65] Together they began exploring the subject of Ufology, and became friends with the ufologist George Van Tassel.[66] After Kimmel was released from a psychiatric ward, Cameron re-established her relationship with him, and in 1959, they were married in a civil ceremony at Santa Monica City Hall; their relationship was strained and they separated soon after.[67]

In 1960, Cameron appeared alongside Hopper in Harrington's first full-length film, Night Tide. The film was a critical success and—despite not receiving a wide distribution—became a cult classic.[68] She was invited to appear in Harrington's next film, Games, although ultimately never did so.[69] After Cameron moved to Venice, Los Angeles,[70] a local arts shop exhibited her work in August 1961.[71] On his return to the U.S. from Europe, Anger moved in with Cameron for a time,[72] before the duo moved into a flat on Silverlake Boulevard in early 1964; Anger remained there before departing for New York City.[73] According to Anger biographer Bill Landis, Cameron had become "a rather formidable maternal figure" in Anger's life.[74] In October 1964, the Cinema Theatre in Los Angeles held an event known as The Transcendental Art of Cameron, which displayed her art and poetry and screened some of her films; Anger arrived and disrupted the event by objecting to the screening of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome without his permission.[75] He then launched a poster campaign, The Cameron File, against his former friend, labelling her "Typhoid Mary of the Occult World".[76] The pair later reconciled, Cameron visiting Anger in San Francisco, where he introduced her to Anton LaVey, the founder of the Church of Satan. LaVey was delighted to meet her, having been a fan of Night Tide.[77]

Later life: 1969–1995

[edit]

In the latter part of the 1960s, Cameron and her daughter moved to the pueblos of Santa Fe, New Mexico,[78] where she developed a friendship with sculptor John Chamberlain and appeared in his art movie, Thumb Suck, which was never released.[79] While in New Mexico she suffered a collapsed lung and required hospitalization.[80] Her health was poor, as she suffered from chronic bronchitis and emphysema (both of which were exacerbated by her chain smoking), while hand tremors prevented her from being able to paint for four years.[81] Returning to California, by 1969 she was living in the Pioneertown sector of Joshua Tree.[82] From there she and her daughter moved to a small bungalow on North Genesee Avenue in the West Hollywood area of Los Angeles, which at the time had become impoverished and associated with crime, sex stores, and adult movie theatres; she remained there for the rest of her life.[83]

By the mid-1980s, Cameron was focusing to a greater extent on her family life, particularly in looking after her grandchildren, who were known to go joyriding in her jeep.[84] Neighbors recall her playing a Celtic harp in her garden and slowly walking her dog around the block while smoking a joint of marijuana.[85] At one point, she was arrested for cultivating cannabis in her home.[86] Cameron became a regular practitioner of Tai chi, took part in group sessions in Bronson Park under the tutelage of Marshall Ho'o, and earned a teaching certificate in the subject.[87] She became very interested in José Argüelles' The Mayan Factor and Charles Musès' The Lion Path, and undertook the Neo-shamanic practices endorsed in the latter.[88] She was also influenced by claims made in the writings of archaeologist Marija Gimbutas about a prehistoric matriarchal society devoted to a goddess.[89] Cameron was very interested in A. S. Raleigh's Woman and Superwoman, taped her own reading of it, and sent copies to her friends and local public radio for broadcast.[89] Throughout all of these disparate spiritual interests, she retained faith in the Thelemic ideas of Crowley.[89]

As well as entertaining old friends who came to visit her in her home,[90] Cameron also met with younger occultists, such as the Thelemite William Breeze and the industrial musician Genesis P-Orridge.[91] Cameron aided Breeze in co-editing a collection of Parsons' occult and libertarian writings, which were published as Freedom is a Two-Edged Sword in 1989.[92] Cameron was acquainted with the experimental film-maker Chick Strand and appeared in the latter's 1979 project Loose Ends, during which she narrated the story of an exorcism.[86] In 1989, an exhibition of her work titled The Pearl of Reprisal was held at the Los Angeles Municipal Art Gallery. It included a selection of her paintings and a screening of Inauguration of the Pleasure Dome and The Wormwood Star, while Cameron attended to provide a candle-lit reading of her poetry.[93]

Death

[edit]In the mid-1990s, Cameron was diagnosed with a brain tumor and underwent radiotherapy treatment, which she supplemented with alternative medicines. The tumor was cancerous and metastasized to her lungs.[94] She died at the age of 73 in the VA Medical Center on July 24, 1995,[95] and underwent the Thelemic last rites, carried out by a high priestess of Ordo Templi Orientis.[50] Her body was cremated and her ashes were scattered in the Mojave Desert.[50] A memorial event was held at Venice's Beyond Baroque Literary Arts Center in August.[50]

Personality

[edit]Cameron preferred to be known by her surname as a mononym.[96] According to historian of Thelema Martin P. Starr, Cameron's "very dominating personality could not brook rivals of any kind".[97] The fashion writer Tim Blanks noted that Cameron was "a charismatic woman" active in the mid-20th century "macho art world", and that it was not surprising how "alluring and dangerous" she must have seemed to Hopper and Stockwell.[98]

Stockwell described Cameron as "a very, very intense personality, but very fascinating".[99] Considering her to be "an out and out witch",[100] Hopper described her as having an "infectious personality" through her presence; she was someone "that you knew [was] different and [she] had a magnetic quality that you wanted to be closer to".[99] The photographer Charles Brittin, who knew Cameron on Los Angeles' artistic circuit, called her "a sweet person with a great personality, not the way some of her friends wanted to picture her to be".[101] Her friend Shirley Berman described her as having "many different crowds of friends, and I think she was a different personality with each crowd ... She wasn't an even personality at all, but she was always a very gracious person."[7]

Artistic style

[edit][Cameron's] art and spiritual life were one. They were indivisible ... But that said, you can be a total sceptic or atheist, or know nothing of her spiritual practice, and still be deeply moved or blown away by her exquisitely rendered, and beautiful envisioned drawings and paintings. It's the work that remains. These sublime treasures that she seems to have captured and brought back from a netherworld for us all to view.

– Biographer Spencer Kansa[102]

The digital media theorist Peter Lunenfeld described Cameron as "one of those people for whom art was life and life was art", and thus an understanding of her life is needed to appreciate her work.[96] Cameron's occult beliefs strongly affected her artworks.[103] According to Priscilla Frank, writing for The Huffington Post, Cameron's artwork merges "Crowley's occult with the surrealism and symbolism of French poets, yielding dark yet whimsical depictions buzzing with otherworldly power".[104] The art curator Philippe Vergne described her work as being on "the edge of surrealism and psychedelia", embodying "an aspect of modernity that deeply doubts and defies cartesian logic at a moment in history when these values have shown their own limitations".[104]

Lunenfeld compared Cameron's black and white pen-and-ink drawings to those of the English artist Aubrey Beardsley, noting that she was capable of a "ferocious, paradoxical line work—simultaneously precise and seductively unrestrained—that functions as both figurative depiction and unabashed emotional talisman".[105] He believed that both "passion and craft" could be seen in her draughtsmanship, but that it also displayed "a guilelessness that is hard to relate to in our post post-ironic moment".[105] He also discussed her lost multi-coloured watercolour paintings that were featured in Harrington's The Wormwood Star, suggesting that they were akin to a storyboard for an unrealised film by the director Alejandro Jodorowsky.[105]

Cameron's biographer Spencer Kansa was of the opinion that Cameron exhibited parallels with the Australian artist and occultist Rosaleen Norton, both in terms of her physical appearance and the similarities between their artistic styles.[106] Harrington also saw similarities in the work of Cameron and the artists Leonora Carrington and Leonor Fini.[107] On the website of the Cameron–Parsons Foundation, Michael Duncan expressed the view that Cameron's work rivals that of "fellow surrealists" like Carrington, Fini, Remedios Varo, and Ithell Colquhoun, while also appearing "fascinatingly prescient" of the works by later artists Kiki Smith, Amy Cutler, Karen Kilimnik, and Hernan Bas.[108] In later years, Cameron would often be erroneously labelled a Beat artist because she inhabited many of the same social circles as prominent Beat poets and writers.[109] Rejecting this label, Kansa instead described Cameron as "a pre-Beat bohemian, whose heart lay in Romanticism".[109]

Legacy

[edit]Cameron's reputation as an artist grew after her death.[110] In 1995, her painting Peyote Vision was included as part of an exhibition on "Beat Culture and the New American" held at the Whitney Museum of American Art in New York City.[111]

Some of her artworks were exhibited alongside those of Crowley and other Thelemites for the 2001 exhibition "Reflections of a New Aeon", held at the Eleven Seven Gallery in California's Long Beach.[112] In 2006, her friend Scott Hobbs established the Cameron–Parsons Foundation to serve as an archive storing and promoting her work.[7] In 2007 a retrospective of Cameron's work was held at the Nicole Klagsbrun Gallery in New York City's Chelsea district, while that same year some of her works appeared in the traveling exhibition "Semina Culture", which was devoted to all of the artists who contributed to Wallace Berman's journal.[113] In 2008, her painting Dark Angel was featured in the "Traces du Sacré" exhibit at the Centre Georges Pompidou in Paris.[98]

Cameron's life was brought to wider attention through the publication of two biographies about Parsons: John Carter's Sex and Rockets and George Pendle's Strange Angel.[114] Cameron was portrayed by Heather Tom.[115] In 2011, Wormwood Star, a biography of Cameron authored by the Briton Spencer Kansa, was published,[116] though it was not authorized by the Cameron–Parsons Foundation.[117] Kansa had spent almost three years in the U.S. researching the book, interviewing many of those who knew Cameron, including several who died shortly after.[118] Kansa stated that most of those whom he interviewed "were immensely generous with their time and recollections".[118] Writing in the Los Angeles Review of Books, Steffie Nelson noted that Kansa did "his due diligence tracking down Cameron's childhood acquaintances and friends" but at the same time was critical of the lack of sources or footnotes.[117]

In 2014, another retrospective, titled "Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman",[119] was held at the Museum of Contemporary Art, Los Angeles.[120] That year, the U.K.-based publisher Fulgur Esoterica released a book featuring images of Cameron's artworks and Parsons' poems.[121] In 2015, a retrospective of her work titled "Cameron: Cinderella of the Wastelands" was held at the Deitch Projects in Soho, New York City, which included an evening in which friends of Cameron's assembled to publicly discuss her legacy.[122] Cameron's aesthetic also influenced the fashion world, designers Pamela Skaist-Levy and Gela Nash-Taylor acknowledging Cameron as a partial inspiration for their Skaist-Taylor label.[98]

References

[edit]Citations

[edit]- ^ Carter 2004, p. 220.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 131; Duncan 2008; Kaczynski 2010, p. 538; Kansa 2011, p. 9; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 131; Kaczynski 2010, p. 538; Kansa 2011, pp. 9–11.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 11–12.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 12, 15.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 13–14.

- ^ a b c Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 17.

- ^ a b Kansa 2011, p. 18.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 131; Kaczynski 2010, p. 538; Kansa 2011, pp. 18–22; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 22–23.

- ^ Duncan 2008; Kaczynski 2010, p. 538; Kansa 2011, p. 24.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 131; Duncan 2008; Kaczynski 2010, p. 538; Kansa 2011, p. 27; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 130; Kansa 2011, pp. 28–29; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 130; Pendle 2005, pp. 259–260; Kansa 2011, pp. 35–37; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Pendle 2005, pp. 263–264; Kansa 2011, p. 29; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 151; Kansa 2011, pp. 37–38.

- ^ Pendle 2005, pp. 267–269; Kansa 2011, pp. 38–39.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 39.

- ^ Starr 2003, p. 320; Carter 2004, p. 158; Pendle 2005, pp. 275, 277; Kansa 2011, p. 39; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 130; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 39–41.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 43–45.

- ^ a b Kansa 2011, pp. 48–49.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 48.

- ^ Pendle 2005, p. 288; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 51–53; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Pendle 2005, pp. 294, 297; Kansa 2011, p. 57.

- ^ Pendle 2005, pp. 294–295; Kansa 2011, pp. 57–63.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 61.

- ^ Pendle 2005, pp. 296–297; Kansa 2011, p. 64.

- ^ Pendle 2005, p. 299; Kansa 2011, p. 65.

- ^ Carter 2004, pp. 177–179; Pendle 2005, pp. 1–6; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 65–66; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 67–68.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 94.

- ^ a b Kansa 2011, p. 74.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 74–75.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 75–77.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 77–79.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 79.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 80–81.

- ^ Starr 2003, p. 328; Carter 2004, p. 184.

- ^ Starr 2003, p. 328.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 82; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 85–86.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 67, 97.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 90, 92.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 88–89.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 90–92.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 188; Kansa 2011, pp. 82–84; Nelson 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 92, 94.

- ^ a b c d Kansa 2011, p. 253.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 97–98.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 100.

- ^ Landis 1995, pp. 74–76; Carter 2004, p. 190; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 104–106; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 114–115.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 190; Kansa 2011, pp. 118–121; Nelson 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 190; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 126, 130; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 47; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 191; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 135–139; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 131.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 140–141.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 121–122.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 141; Fredman 2010, p. 1.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 144; Nelson 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 143, 150.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 152–154, 157; Nelson 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 157–158.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 173–174; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 191; Kansa 2011, pp. 174–171; Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 207.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 174.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 177.

- ^ Landis 1995, pp. 100–101; Kansa 2011, pp. 183–187.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 190.

- ^ Landis 1995, p. 81.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 191–192.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 193–194.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 214.

- ^ Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, p. 215; Laden 2014.

- ^ Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 217–218; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 226–227.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 227.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 223–224; Nelson 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 227; Nelson 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 238; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 244.

- ^ a b Kansa 2011, pp. 233–234.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 236; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 241.

- ^ a b c Kansa 2011, p. 247.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 242.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 239.

- ^ Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, p. 249; Nelson 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 195; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, p. 249; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 250, 253.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 195; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, p. 252; Laden 2014.

- ^ a b Lunenfeld 2015, p. 91.

- ^ Starr 2003, p. 320.

- ^ a b c Blanks 2013, p. 246.

- ^ a b Kansa 2011, p. 141.

- ^ Landis 1995, p. 72.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 178.

- ^ Stevens 2011, p. 25.

- ^ Laden 2014; Martinez 2015.

- ^ a b Frank 2014.

- ^ a b c Lunenfeld 2015, p. 92.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 137.

- ^ Kansa 2011, pp. 136, 137.

- ^ Duncan 2008.

- ^ a b Kansa 2011, p. 143.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 255; Laden 2014.

- ^ Carter 2004, p. 195; Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, p. 255.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 256.

- ^ Duncan 2008; Kansa 2011, pp. 257–258; Laden 2014.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 255.

- ^ Kansa 2011, p. 257.

- ^ Stevens 2011, p. 24; Blanks 2013, p. 246.

- ^ a b Nelson 2014.

- ^ a b Stevens 2011, p. 24.

- ^ Lipschutz 2014.

- ^ Nelson 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Frank 2014; Laden 2014.

- ^ Yaeger 2015; Chidester 2015; Martinez 2015.

Works cited

[edit]- Blanks, Tim (March 2013). "Witch's Crew" (PDF). W Magazine. pp. 244–245.

- Carter, John (2004). Sex and Rockets: The Occult World of Jack Parsons (new ed.). Port Townsend: Feral House. ISBN 978-0-922915-97-2.

- Chidester, Brian (September 8, 2015). "Cameron: Cinderella of the Wastelands". The Village Voice. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Duncan, Michael (2008). "Cameron". Cameron Parsons Foundation. Archived from the original on June 5, 2008. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Frank, Priscilla (August 8, 2014). "Meet Cameron, The Countercultural Icon Who Bewitched Los Angeles". The Huffington Post. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Fredman, Stephen (2010). Contextual Practice: Assemblage and the Erotic in Postwar Poetry and Art. Stanford: Stanford University Press. ISBN 978-0-804763-58-5.

- Kaczynski, Richard (2010). Perdurabo: The Life of Aleister Crowley (second ed.). Berkeley, CA: North Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-0-312-25243-4.

- Kansa, Spencer (2011). Wormwood Star: The Magickal Life of Marjorie Cameron. Oxford: Mandrake. ISBN 978-1-906958-08-4.

- Laden, Tanja M. (October 8, 2014). "Cameron's Connections to Scientology and Powerful Men Once Drew Headlines, But Now Her Art Is Getting Its Due". LA Weekly. Archived from the original on February 19, 2015.

- Landis, Bill (1995). Anger: The Unauthorized Biography of Kenneth Anger. New York: HarperCollins. ISBN 978-0-06-016700-4.

- Lipschutz, Yael (2014). Cameron: Songs for the Witch Woman. Cameron Parsons Foundation. ISBN 978-0-692-28952-5.

- Lunenfeld, Peter (January 2015). "Cameron: The Season of the Witch" (PDF). Artforum: 91–92.

- Martinez, Alanna (October 2, 2015). "Deitch Projects Presents the Uncensored Story of LA Artist/Occultist Marjorie Cameron". Observer. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

- Nelson, Steffie (October 8, 2014). "Cameron, Witch of the Art World". Los Angeles Review of Books. Archived from the original on April 14, 2015.

- Pendle, George (2005). Strange Angel: The Otherworldly Life of Rocket Scientist John Whiteside Parsons. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 978-0-7538-2065-0.

- Starr, Martin P. (2003). The Unknown God: W.T. Smith and the Thelemites. Bollingbrook: Teitan Press. ISBN 978-0-933429-07-9.

- Stevens, Matthew Levi (August 2011). "Interview with Spencer Kansa". The Cauldron. 141: 24–27. ISSN 0964-5594.

- Yaeger, Lynn (September 10, 2015). "The Cameron Retrospective Might Be the Most Stunning Show This Fall". Vogue. Archived from the original on January 26, 2016. Retrieved April 12, 2016.

External links

[edit]- Cameron-Parsons Foundation

- Marjorie Cameron at IMDb

- The Wormwood Star (1955), a short film portrait of Cameron by Curtis Harrington.

- 1922 births

- 1995 deaths

- 20th-century American actresses

- 20th-century American poets

- 20th-century apocalypticists

- American contemporary artists

- American occultists

- American Thelemites

- Art in Greater Los Angeles

- American feminist artists

- Feminist spirituality

- People from Belle Plaine, Iowa

- People from Joshua Tree, California

- Military personnel from Iowa

- United States Navy sailors

- WAVES personnel