Ceasefire

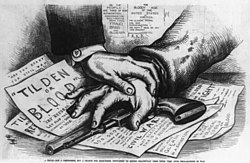

By Thomas Nast in Harper's Weekly, February 17, 1877, p. 132.

A ceasefire (also known as a truce),[1] also spelled cease-fire (the antonym of 'open fire'),[2] is a stoppage of a war in which each side agrees with the other to suspend aggressive actions often due to mediation by a third party.[3][4] Ceasefires may be between state actors or involve non-state actors.[1]

Ceasefires may be declared as part of a formal treaty but also as part of an informal understanding between opposing forces.[2] They may occur via mediation or otherwise as part of a peace process or be imposed by United Nations Security Council resolutions via Chapter VII of the United Nations Charter.[2] A ceasefire can be temporary with an intended end date or may be intended to last indefinitely. A ceasefire is distinct from an armistice in that the armistice is a formal end to a war whereas a ceasefire may be a temporary stoppage.[5]

The immediate goal of a ceasefire is to stop violence but the underlying purposes of ceasefires vary. Ceasefires may be intended to meet short-term limited needs (such as providing humanitarian aid), manage a conflict to make it less devastating, or advance efforts to peacefully resolve a dispute.[1] An actor may not always intend for a ceasefire to advance the peaceful resolution of a conflict but instead give the actor an upper hand in the conflict (for example, by re-arming and repositioning forces or attacking an unsuspecting adversary), which creates bargaining problems that may make ceasefires less likely to be implemented and less likely to be durable if implemented.[3][1][6]

The durability of ceasefire agreements is affected by several factors, such as demilitarized zones, withdrawal of troops and third-party guarantees and monitoring (e.g. peacekeeping). Ceasefire agreements are more likely to be durable when they reduce incentives to attack, reduce uncertainty about the adversary's intentions, and when mechanisms are put in place to prevent accidents from spiraling into conflict.[3]

Overview

[edit]Ceasefire agreements are more likely to be reached when the costs of conflict are high and when the actors in a conflict have lower audience costs.[7] Scholars emphasize that war termination is more likely to occur when actors have more information about each other, when actors can make credible commitments, and when the domestic political situation makes it possible for leaders to make war termination agreements without incurring domestic punishment.[8]

By one estimate, there were at least 2202 ceasefires across 66 countries in 109 civil conflicts over the period 1989–2020.[1]

Historical examples

[edit]Historically, the concept of a ceasefire existed at least by the time of the Middle Ages, when it was known as a 'truce of God'.[9]

World War I

[edit]During World War I, on December 24, 1914, there was an unofficial ceasefire on the Western Front as France, the United Kingdom, and Germany observed Christmas. There are accounts that claimed the unofficial ceasefire took place throughout the week leading to Christmas, and that British and German troops exchanged seasonal greetings and songs between their trenches.[10] The ceasefire was brief but spontaneous. Beginning when German soldiers lit Christmas trees, it quickly spread up and down the Western Front.[11] One account described the development in the following words:

It was good to see the human spirit prevailed amongst all sides at the front, the sharing and fraternity. All was well until the higher echelons of command got to hear about the effect of the ceasefire, whereby their wrath ensured a return to hostilities.[12]

There was no peace treaty signed during the Christmas truce, and the war resumed after a few days.

Karachi Agreement

[edit]The Karachi Agreement of 1949 was signed by the military representatives of India and Pakistan, supervised by the United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan, establishing a cease-fire line in Kashmir following the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947.[13]

Korean War

[edit]On November 29, 1952, the US president-elect, Dwight D. Eisenhower, went to Korea to see how to end the Korean War. With the UN's acceptance of India's proposed armistice, the ceasefire between the UN Command on the one side and the Korean People's Army (KPA) and the People's Volunteer Army (PVA) on the other took hold at approximately the 38th parallel north. These parties signed the Korean Armistice Agreement on July 27, 1953[14][15] but South Korean President Syngman Rhee, who attacked the ceasefire proceedings, did not.[16] Upon agreeing to the ceasefire which called upon the governments of South Korea, the United States, North Korea and China to participate in continued peace talks, the principal belligerents of the war established the Korean Demilitarized Zone (DMZ) and it has since been patrolled by the joint Republic of Korea Army, US, and UN Command on the one side and the KPA on the other. The war is considered to have ended at that point even though there still is no peace treaty.

Vietnam War

[edit]On New Years Day, 1968, Pope Paul VI convinced South Vietnam and the United States to declare a 24-hour-truce. However, the Viet Cong and North Vietnam did not adhere to the truce, and ambushed the 2nd Battalion, Republic of Vietnam Marine Division, 10 minutes after midnight in Mỹ Tho. The Viet Cong would also attack a U.S. Army fire support base near Saigon, causing more casualties.[17]

On January 15, 1973, US President Richard Nixon ordered a ceasefire of the aerial bombings in North Vietnam. The decision came after Henry Kissinger, the National Security Advisor to the President, returned to Washington, D.C., from Paris, France, with a draft peace proposal. Combat missions continued in South Vietnam. By January 27, 1973, all parties of the Vietnam War signed a ceasefire as a prelude to the Paris Peace Accord.

Gulf War

[edit]After Iraq was driven out of Kuwait by US-led coalition forces during Operation Desert Storm, Iraq and the UN Security Council signed a ceasefire agreement on March 3, 1991.[18] Subsequently, throughout the 1990s, the U.N. Security Council passed numerous resolutions calling for Iraq to disarm its weapons of mass destruction unconditionally and immediately. Because no peace treaty was signed after the Gulf War, the war still remained in effect, including an alleged assassination attempt of former US President George H. W. Bush by Iraqi agents while on a visit to Kuwait;[citation needed] Iraq being bombed in June 1993 as a response, Iraqi forces firing on coalition aircraft patrolling the Iraqi no-fly zones, US President Bill Clinton's bombing of Baghdad in 1998 during Operation Desert Fox, and an earlier 1996 bombing of Iraq by the US during Operation Desert Strike. The war remained in effect until 2003, when US and UK forces invaded Iraq and toppled Saddam Hussein's regime from power.

Kashmir conflict

[edit]A UN-mediated ceasefire was agreed between India and Pakistan, on 1 January 1949, ending the Indo-Pakistani War of 1947 (also called the 1947 Kashmir War). Fighting broke out between the two newly independent countries in Kashmir in October 1947, with India intervening on behalf of the princely ruler of Kashmir, who had joined India, and Pakistan supporting the rebels. The fighting was limited to Kashmir, but, apprehensive that it might develop into a full-scale international war, India referred the matter to the UN Security Council under Article 35 of the UN Charter, which addresses situations "likely to endanger the maintenance of international peace". The Security Council set up the dedicated United Nations Commission for India and Pakistan, which mediated for an entire year as the fighting continued. After several UN resolutions outlining a procedure for resolving the dispute via a plebiscite, a ceasefire agreement was reached between the countries towards the end of December 1948, which came into effect in the New Year. The Security Council set up the United Nations Military Observer Group for India and Pakistan (UNMOGIP) to monitor the ceasefire line.[19] India declared a ceasefire in Kashmir Valley during Ramadan in 2018.[citation needed]

Northern Ireland

[edit]The Irish Republican Army held several Christmas ceasefires (usually referred to as truces) during the Northern Ireland conflict.[20][21]

Israeli–Palestinian conflict

[edit]

An example of a ceasefire in the Israeli–Palestinian conflict was announced between Israel and the Palestinian National Authority on February 8, 2005. When announced, chief Palestinian negotiator Saeb Erekat publicly defined the ceasefire as follows: "We have agreed that today President Mahmoud Abbas will declare a full cessation of violence against Israelis anywhere and Prime Minister Ariel Sharon will declare a full cessation of violence and military activities against Palestinians anywhere."[22] On November 21, 2023, Qatar announced that they had negotiated a truce between Israel and Hamas would pause Gaza fighting, allow for the release of some hostages and bring more aid to Palestinian civilians. As part of the deal, 50 hostages held by Hamas were released while Israel released 150 Palestinian prisoners.[23]

Syrian Civil War

[edit]Several attempts have been made to broker ceasefires in the Syrian Civil War.[24][25][26]

Russo-Ukrainian War

[edit]Several attempts have been made to broker ceasefires during the Russian invasion of Ukraine.[27][28][29]

In May 2023, Donald Trump told the UK's GB news that as US president he would end the war within 24 hours, given that he had good relationships with the leaders of Ukraine and Russia. He added that it would be easy to conclude a ceasefire agreement to end the war. [30]

2020 global ceasefire

[edit]The 2020 global ceasefire was a response to a formal appeal by United Nations Secretary-General António Manuel de Oliveira Guterres on March 23 for a global ceasefire as part of the United Nations' response to the COVID-19 coronavirus pandemic. On 24 June 2020, 170 UN Member States and Observers signed a non-binding statement in support of the appeal, rising to 172 on 25 June 2020, and on 1 July 2020, the UN Security Council passed a resolution demanding a general and immediate global cessation of hostilities for at least 90 days.[31][32]

2024 Israel–Hezbollah ceasefire

[edit]The 2024 Israel–Hezbollah ceasefire was announced by United States President Joe Biden on November 26, 2024.[33]

See also

[edit]- 2020 Nagorno-Karabakh ceasefire agreement

- Armistice

- De-escalation

- Demilitarized zone

- Olympic Truce

- Korean Armistice Agreement

- Peacebuilding

- Peacemaking

- Peace process

- Peace treaty

- Surrender (military)

References

[edit]- ^ a b c d e Clayton, Govinda; Nygård, Håvard Mokleiv; Rustad, Siri Aas; Strand, Håvard (2023). "Ceasefires in Civil Conflict: A Research Agenda". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 67 (7–8): 1279–1295. doi:10.1177/00220027221128300. hdl:20.500.11850/576568. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 252793375.

- ^ a b c Forster, Robert A. (2019), "Ceasefires", in Romaniuk, Scott; Thapa, Manish; Marton, Péter (eds.), The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Global Security Studies, Springer, pp. 1–8, doi:10.1007/978-3-319-74336-3_8-2, ISBN 978-3-319-74336-3, S2CID 239326729

- ^ a b c Fortna, Virginia Page (2004). Peace Time: Cease-Fire Agreements and the Durability of Peace. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-18795-2. OCLC 1044838807.

- ^ "Ceasefire". Oxford Public International Law. doi:10.1093/law:epil/9780199231690 (inactive 1 November 2024). Retrieved 2024-03-14.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: DOI inactive as of November 2024 (link) - ^ "Ceasefires are fragile: Can Israel and Hamas find peace?". Good Authority. 2025.

- ^ Sosnowski, Marika (2023). Redefining Ceasefires: Wartime Order and Statebuilding in Syria. Cambridge University Press. doi:10.1017/9781009347204. ISBN 978-1-009-34722-8.

- ^ Clayton, Govinda; Nygård, Håvard Mokleiv; Rustad, Siri A.; Strand, Håvard (2022). "Costs and Cover: Explaining the Onset of Ceasefires in Civil Conflict". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 67 (7–8): 1296–1324. doi:10.1177/00220027221129195. hdl:10852/99393. ISSN 0022-0027. S2CID 252739885.

- ^ "How the War in Ukraine Might End". The New Yorker. 2022-09-29.

- ^ Bailey, Sydney D. (1977). "Cease-Fires, Truces, and Armistices in the Practice of the UN Security Council". The American Journal of International Law. 71 (3): 461–473. doi:10.2307/2200012. ISSN 0002-9300. JSTOR 2200012. S2CID 147435735.

- ^ Evans, Abigail; Bartollas, Clemens; Graham, Gordon; Henke, Kenneth (2011). The Long Shadow of Emile Cailliet: Faith, Philosophy, and Theological Education. Eugene, OR: Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 9781610971126.

- ^ Brockell, Gillian (December 24, 2017). "The Christmas Truce miracle: Soldiers put down their guns to sing carols and drink wine". Washington Post. Retrieved 2018-08-27.

- ^ Wilson, Ross (2016). Cultural Heritage of the Great War in Britain. Oxon: Routledge. p. 74. ISBN 9781409445739.

- ^ Wirsing, Robert (1998). War Or Peace on the Line of Control?: The India-Pakistan Dispute Over Kashmir Turns Fifty. IBRU. p. 9. ISBN 978-1-897643-31-0.

- ^ "Document for July 27th: Armistice Agreement for the Restoration of the South Korean State". Archived from the original on 19 October 2012. Retrieved 13 December 2012.

- ^ "Korean War Armistice Agreement". FindLaw. Canada and United States: Thomson Reuters. 27 July 1953. Archived from the original on 5 March 2014. Retrieved 5 March 2014.

- ^ Kollontai, Ms Pauline; Kim, Professor Sebastian C. H.; Hoyland, Revd Greg (2013-05-28). Peace and Reconciliation: In Search of Shared Identity. Ashgate Publishing, Ltd. p. 111. ISBN 978-1-4094-7798-3.

- ^ Kurlansky, Mark. (2004). 1968 : the year that rocked the world (1st ed.). New York: Ballantine. pp. 3, 13. ISBN 0-345-45581-9. OCLC 53929433.

- ^ "BBC News | Saddam's Iraq: Key events". news.bbc.co.uk. Archived from the original on 2003-12-17. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ Schofield, Victoria (2003) [First published in 2000], Kashmir in Conflict, London and New York: I. B. Taurus & Co, pp. 68–69, ISBN 978-1860648984

- ^ "I.R.A. Provisionals Announce a Christmas Truce". The New York Times. 21 December 1974.

- ^ "IRA Declares Usual Christmas Truce". Los Angeles Times. 24 December 1993.

- ^ Wedeman, Ben; Raz, Guy; Koppel, Andrea (2005-02-07). "Mideast cease-fire expected Tuesday". CNN. Archived from the original on 2005-02-08. Retrieved 2007-01-03.

- ^ Federman, Josef; Jeffrey, Jack (21 November 2023). "Qatar announces Israel-Hamas truce-for-hostages deal that would pause Gaza fighting, bring more aid". AP News. Associated Press. Retrieved 22 November 2023.

- ^ Lundgren, Magnus (2016). "Mediation in Syria: initiatives, strategies, and obstacles, 2011–2016". Contemporary Security Policy. 37 (2): 273–288. doi:10.1080/13523260.2016.1192377. S2CID 156447200.

- ^ Karakus, Dogukan Cansin; Svensson, Isak (2020-05-18). "Between the Bombs: Exploring Partial Ceasefires in the Syrian Civil War, 2011–2017". Terrorism and Political Violence. 32 (4): 681–700. doi:10.1080/09546553.2017.1393416. ISSN 0954-6553. S2CID 149165856.

- ^ Lundgren, Magnus; Svensson, Isak; Karakus, Dogukan Cansin (2020-05-18). "Local Ceasefires and De-escalation: Evidence From the Syrian Civil War". Journal of Conflict Resolution. 67 (7–8): 1350–1375. doi:10.1177/00220027221148655.

- ^ "Xi Jinping Hosts Brazil's Lula in Controversial Diplomatic Push for Ukraine Cease-Fire". Time. 12 April 2023.

- ^ "Putin Quietly Signals He Is Open to a Cease-Fire in Ukraine". The New York Times. 23 December 2023.

- ^ "Exclusive: Putin's suggestion of Ukraine ceasefire rejected by United States, sources say". Reuters. 13 February 2024.

- ^ Soraya Ebrahimi (4 May 2023). "'I could end Ukraine war in 24 hours', Donald Trump tells UK TV". The Nationals.

- ^ "S/RES/2532(2020) - E - S/RES/2532(2020)". undocs.org. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ "Stalled Security Council resolution adopted, backing UN's global humanitarian ceasefire call". UN News. 2020-07-01. Retrieved 2020-08-01.

- ^ "Stalled Security Council resolution adopted, backing UN's global humanitarian ceasefire call". NBCAdde News. 2020-07-01. Retrieved 2024-11-26.

Further reading

[edit]- Clayton Govinda, Nygård Håvard Mokleiv, Strand Håvard, Rustad Siri Aas, Wiehler Claudia, Sagård Tora, Landsverk Peder, Ryland Reidun, Sticher Valerie, Wink Emma, Bara Corrine. 2022. “Introducing the Civil Conflict Ceasefire Dataset.” Journal of Conflict Resolution.

- Akebo, Malin. (2016). Ceasefire Agreements and Peace Processes: A Comparative Study. Routledge.

- Colletta, Nat. (2011). "Mediating ceasefires and cessations of hostilities agreements in the framework of peace processes." In Peacemaking: From Practice to Theory. Praeger, 135–147.

- Forster, Robert A. (2019). Ceasefires. In The Palgrave Encyclopedia of Global Security Studies. Palgrave.

- Fortna, Virginia Page. (2004). Peace Time: Cease-fire Agreements and the Durability of Peace. Princeton University Press.

- Williams, R., Gustafson, D., Gent, S., & Crescenzi, M. (2021). "A latent variable approach to measuring and explaining peace agreement strength." Political Science Research and Methods, 9(1), 89–105.