Mao Zedong

Mao Zedong | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

毛泽东 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

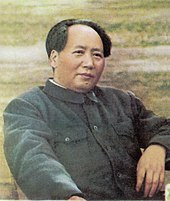

Mao in 1959 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Chinese Communist Party | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 20 March 1943 – 9 September 1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Zhang Wentian (as General Secretary) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| 1st Chairman of the People's Republic of China | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 27 September 1954 – 27 April 1959 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Zhou Enlai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy | Zhu De | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Liu Shaoqi | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central Military Commission | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 8 September 1954 – 9 September 1976 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Deputy |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Hua Guofeng | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Central People's Government | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 1 October 1949 – 27 September 1954 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Premier | Zhou Enlai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established Li Zongren (as President of the Republic of China) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chairman of the Chinese People's Political Consultative Conference | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| In office 9 October 1949 – 25 December 1954 | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Preceded by | Office established | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Succeeded by | Zhou Enlai | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Personal details | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Born | 26 December 1893 Shaoshan, Hunan, Qing China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Died | 9 September 1976 (aged 82) Beijing, China | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Resting place | Chairman Mao Memorial Hall, Beijing | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Political party | CCP (from 1921) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Other political affiliations | Kuomintang (1925–1926) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Spouses | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Parents | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Alma mater | Hunan First Normal University | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Signature | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Chinese name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 毛泽东 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 毛澤東 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Courtesy name | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Simplified Chinese | 润之 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Traditional Chinese | 潤之 | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Central institution membership Other offices held

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Mao Zedong[a] (26 December 1893 – 9 September 1976), also known as Chairman Mao, was a Chinese politician, political theorist, military strategist, poet, and revolutionary who was the founder of the People's Republic of China (PRC). He led the country from its establishment in 1949 until his death in 1976, while also serving as the chairman of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP) during that time. His theories are known as Maoism.

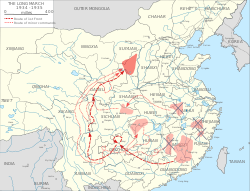

Mao was the son of a peasant in Shaoshan, Hunan. He supported Chinese nationalism and had an anti-imperialist outlook early in his life, and was influenced by the events of the Xinhai Revolution of 1911 and the May Fourth Movement of 1919. He later adopted Marxism–Leninism while working at Peking University as a librarian. He became a founding member of the Chinese Communist Party (CCP), leading the Autumn Harvest Uprising in 1927. During the Chinese Civil War between the Kuomintang (KMT) and the CCP, Mao helped to found the Chinese Red Army, led the Jiangxi Soviet's radical land reform policies, and ultimately became head of the CCP during the Long March. Although the CCP temporarily allied with the KMT under the Second United Front during the Second Sino-Japanese War (1937–1945), China's civil war resumed after Japan's surrender. Mao's forces defeated the Nationalist government, which withdrew to Taiwan in 1949.

On 1 October 1949, Mao proclaimed the foundation of the PRC, a Marxist–Leninist single-party state controlled by the CCP. In the following years he solidified his control through the land reform campaign against landlords, the Campaign to Suppress Counterrevolutionaries, the "Three-anti and Five-anti Campaigns", and through a truce in the Korean War, which altogether resulted in the deaths of several million Chinese. From 1953 to 1958, Mao played an important role in enforcing command economy in China, constructing the first Constitution of the PRC, launching an industrialisation program, and initiating military projects such as the "Two Bombs, One Satellite" project and Project 523. His foreign policies during this time were dominated by the Sino-Soviet split which drove a wedge between China and the Soviet Union. In 1955, Mao launched the Sufan movement, and in 1957 he launched the Anti-Rightist Campaign, in which at least 550,000 people, mostly intellectuals and dissidents, were persecuted. In 1958, he launched the Great Leap Forward that aimed to transform China's economy from agrarian to industrial, which led to the Great Chinese Famine and the deaths of 15–55 million people between 1958 and 1962.

In 1963, Mao launched the Socialist Education Movement, and in 1966 he initiated the Cultural Revolution, a program to remove "counter-revolutionary" elements in Chinese society which lasted 10 years and was marked by violent class struggle, widespread destruction of cultural artifacts, and an unprecedented elevation of Mao's cult of personality. Tens of millions of people were persecuted during the Revolution, while the estimated number of deaths ranges from hundreds of thousands to millions. After years of ill health, Mao suffered a series of heart attacks in 1976 and died at the age of 82. During the Mao era, China's population grew from around 550 million to over 900 million while the government did not strictly enforce its family planning policy. During his leadership tenure, China was heavily involved with other Asian communist conflicts such as the Korean War, the Vietnam War, and the Cambodian Civil War.

Mao is considered one of the most influential figures of the 20th century. Mao's policies were responsible for a vast number of deaths, with estimates ranging from 40 to 80 million victims due to starvation, persecution, prison labour, and mass executions, and his government has been described as totalitarian. He has been also credited with transforming China from a semi-colony to a leading world power by advancing literacy, women's rights, basic healthcare, primary education, and improving life expectancy. Mao is revered as a national hero who liberated the country from foreign occupation and exploitation in China. He became an ideological figurehead and a prominent influence over the international communist movement, being endowed with remembrance, admiration and a cult of personality both during and after his life.

English romanisation of name

During Mao's lifetime, the English-language media universally rendered his name as Mao Tse-tung, using the Wade–Giles system of transliteration though with the circumflex accent in the syllable Tsê dropped. Due to its recognizability, the spelling was used widely, even by the PRC's foreign ministry after Hanyu Pinyin became the PRC's official romanisation system for Mandarin Chinese in 1958; the well-known booklet of Mao's political statements, The Little Red Book, was officially entitled Quotations from Chairman Mao Tse-tung in English translations. While the pinyin-derived spelling Mao Zedong is increasingly common, the Wade–Giles-derived spelling Mao Tse-tung continues to be used in modern publications to some extent.[2]

Early life

Youth and the Xinhai Revolution: 1893–1911

Mao Zedong was born on 26 December 1893, near Shaoshan village in Hunan.[3] His father, Mao Yichang, was a formerly impoverished peasant who had become one of the wealthiest farmers in Shaoshan. Growing up in rural Hunan, Mao described his father as a stern disciplinarian, who would beat him and his three siblings, the boys Zemin and Zetan, as well as an adopted sister/cousin, Zejian.[4] Mao's mother, Wen Qimei, was a devout Buddhist who tried to temper her husband's strict attitude.[5] Mao too became a Buddhist, but abandoned this faith in his mid-teenage years.[5] At age 8, Mao was sent to Shaoshan Primary School. Learning the value systems of Confucianism, he later admitted that he did not enjoy the classical Chinese texts preaching Confucian morals, instead favouring classic novels like Romance of the Three Kingdoms and Water Margin.[6] At age 13, Mao finished primary education, and his father united him in an arranged marriage to the 17-year-old Luo Yixiu, thereby uniting their land-owning families. Mao refused to recognise her as his wife, becoming a fierce critic of arranged marriage and temporarily moving away. Luo was locally disgraced and died in 1910 at 20 years old.[7]

Working on his father's farm, Mao read voraciously[8] and developed a "political consciousness" from Zheng Guanying's booklet which lamented the deterioration of Chinese power and argued for the adoption of representative democracy.[9] Mao also read translations of works by Western authors including Adam Smith, Montesquieu, Jean-Jacques Rousseau, Charles Darwin, and Thomas Huxley.[10]: 34 Interested in history, Mao was inspired by the military prowess and nationalistic fervour of George Washington and Napoleon Bonaparte.[11] His political views were shaped by Gelaohui-led protests which erupted following a famine in Changsha, the capital of Hunan; Mao supported the protesters' demands, but the armed forces suppressed the dissenters and executed their leaders.[12] The famine spread to Shaoshan, where starving peasants seized his father's grain. He disapproved of their actions as morally wrong, but claimed sympathy for their situation.[13] At age 16, Mao moved to a higher primary school in nearby Dongshan,[14] where he was bullied for his peasant background.[15]

In 1911, Mao began middle school in Changsha.[16] Revolutionary sentiment was strong in the city, where there was widespread animosity towards Emperor Puyi's absolute monarchy and many were advocating republicanism. The republicans' figurehead was Sun Yat-sen, an American-educated Christian who led the Tongmenghui society.[17] In Changsha, Mao was influenced by Sun's newspaper, The People's Independence (Minli bao),[18] and called for Sun to become president in a school essay.[19] As a symbol of rebellion against the Manchu monarch, Mao and a friend cut off their queue pigtails, a sign of subservience to the emperor.[20]

Inspired by Sun's republicanism, the army rose up across southern China, sparking the Xinhai Revolution. Changsha's governor fled, leaving the city in republican control.[21] Supporting the revolution, Mao joined the rebel army as a private soldier, but was not involved in fighting or combat. The northern provinces remained loyal to the emperor, and hoping to avoid a civil war, Sun—proclaimed "provisional president" by his supporters—compromised with the monarchist general Yuan Shikai. The monarchy was abolished, creating the Republic of China, but the monarchist Yuan became president. With the revolution over, Mao resigned from the army in 1912, after six months as a soldier.[22] Around this time, Mao discovered socialism from a newspaper article; proceeding to read pamphlets by Jiang Kanghu, the student founder of the Chinese Socialist Party, Mao remained interested yet unconvinced by the idea.[23]

Fourth Normal School of Changsha: 1912–1919

Over the next few years, Mao Zedong enrolled and dropped out of a police academy, a soap-production school, a law school, an economics school, and the government-run Changsha Middle School.[24] Studying independently, he spent much time in Changsha's library, reading core works of classical liberalism such as Adam Smith's The Wealth of Nations and Montesquieu's The Spirit of the Laws, as well as the works of western scientists and philosophers such as Darwin, Mill, Rousseau, and Spencer.[25] Viewing himself as an intellectual, years later he admitted that at this time he thought himself better than working people.[26] He was inspired by Friedrich Paulsen, a neo-Kantian philosopher and educator whose emphasis on the achievement of a carefully defined goal as the highest value led Mao to believe that strong individuals were not bound by moral codes but should strive for a great goal.[27] His father saw no use in his son's intellectual pursuits, cut off his allowance and forced him to move into a hostel for the destitute.[28]

Mao wanted to become a teacher and enrolled at the Fourth Normal School of Changsha, which soon merged with the First Normal School of Hunan, widely seen as the best in Hunan.[29] Befriending Mao, professor Yang Changji urged him to read a radical newspaper, New Youth (Xin qingnian), the creation of his friend Chen Duxiu, a dean at Peking University. Although he was a supporter of Chinese nationalism, Chen argued that China must look to the west to cleanse itself of superstition and autocracy.[30] In his first school year, Mao befriended an older student, Xiao Zisheng; together they went on a walking tour of Hunan, begging and writing literary couplets to obtain food.[31]

A popular student, in 1915 Mao was elected secretary of the Students Society. He organised the Association for Student Self-Government and led protests against school rules.[32] Mao published his first article in New Youth in April 1917, instructing readers to increase their physical strength to serve the revolution.[33] He joined the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi (Chuan-shan Hsüeh-she), a revolutionary group founded by Changsha literati who wished to emulate the philosopher Wang Fuzhi.[34] In spring 1917, he was elected to command the students' volunteer army, set up to defend the school from marauding soldiers.[35] Increasingly interested in the techniques of war, he took a keen interest in World War I, and also began to develop a sense of solidarity with workers.[36] Mao undertook feats of physical endurance with Xiao Zisheng and Cai Hesen, and with other young revolutionaries they formed the Renovation of the People Study Society in April 1918 to debate Chen Duxiu's ideas. Desiring personal and societal transformation, the Society gained 70–80 members, many of whom would later join the Communist Party.[37] Mao graduated in June 1919, ranked third in the year.[38]

Early revolutionary activity

Beijing, anarchism, and Marxism: 1917–1919

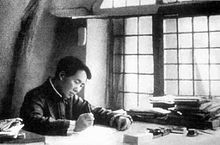

Mao moved to Beijing, where his mentor Yang Changji had taken a job at Peking University.[39] Yang thought Mao exceptionally "intelligent and handsome",[40] securing him a job as assistant to the university librarian Li Dazhao, who would become an early Chinese Communist.[41] Li authored a series of New Youth articles on the October Revolution in Russia, during which the Communist Bolshevik Party under the leadership of Vladimir Lenin had seized power. Lenin was an advocate of the socio-political theory of Marxism, first developed by the German sociologists Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, and Li's articles added Marxism to the doctrines in Chinese revolutionary movement.[42]

Becoming "more and more radical", Mao was initially influenced by Peter Kropotkin's anarchism, which was the most prominent radical doctrine of the day. Chinese anarchists, such as Cai Yuanpei, Chancellor of Peking University, called for complete social revolution in social relations, family structure, and women's equality, rather than the simple change in the form of government called for by earlier revolutionaries. He joined Li's Study Group and "developed rapidly toward Marxism" during the winter of 1919.[43] Paid a low wage, Mao lived in a cramped room with seven other Hunanese students, but believed that Beijing's beauty offered "vivid and living compensation".[44] A number of his friends took advantage of the anarchist-organised Mouvement Travail-Études to study in France, but Mao declined, perhaps because of an inability to learn languages.[45] Mao raised funds for the movement, however.[10]: 35

At the university, Mao was snubbed by other students due to his rural Hunanese accent and lowly position. He joined the university's Philosophy and Journalism Societies and attended lectures and seminars by the likes of Chen Duxiu, Hu Shih, and Qian Xuantong.[46] Mao's time in Beijing ended in the spring of 1919, when he travelled to Shanghai with friends who were preparing to leave for France.[47] He did not return to Shaoshan, where his mother was terminally ill. She died in October 1919 and her husband died in January 1920.[48]

New Culture and political protests: 1919–1920

On 4 May 1919, students in Beijing gathered at Tiananmen to protest the Chinese government's weak resistance to Japanese expansion in China. Patriots were outraged at the influence given to Japan in the Twenty-One Demands in 1915, the complicity of Duan Qirui's Beiyang government, and the betrayal of China in the Treaty of Versailles, wherein Japan was allowed to receive territories in Shandong which had been surrendered by Germany. These demonstrations ignited the nationwide May Fourth Movement and fuelled the New Culture Movement which blamed China's diplomatic defeats on social and cultural backwardness.[49]

In Changsha, Mao had begun teaching history at the Xiuye Primary School[50] and organising protests against the pro-Duan Governor of Hunan Province, Zhang Jingyao, popularly known as "Zhang the Venomous" due to his corrupt and violent rule.[51] In late May, Mao co-founded the Hunanese Student Association with He Shuheng and Deng Zhongxia, organising a student strike for June and in July 1919 began production of a weekly radical magazine, Xiang River Review. Using vernacular language that would be understandable to the majority of China's populace, he advocated the need for a "Great Union of the Popular Masses", and strengthened trade unions able to wage non-violent revolution.[clarification needed] His ideas were not Marxist, but heavily influenced by Kropotkin's concept of mutual aid.[52]

Zhang banned the Student Association, but Mao continued publishing after assuming editorship of the liberal magazine New Hunan (Xin Hunan) and authored articles in popular local newspaper Ta Kung Pao. Several of these advocated feminist views, calling for the liberation of women in Chinese society; Mao was influenced by his forced arranged-marriage.[53] In fall 1919, Mao organized a seminar in Changsha studying economic and political issues, as well as ways to unite the people, the feasibility of socialism, and issues regarding Confucianism.[54] During this period, Mao involved himself in political work with manual laborers, setting up night schools and trade unions.[54] In December 1919, Mao helped organise a general strike in Hunan, securing some concessions, but Mao and other student leaders felt threatened by Zhang, and Mao returned to Beijing, visiting the terminally ill Yang Changji.[55] Mao found that his articles had achieved a level of fame among the revolutionary movement, and set about soliciting support in overthrowing Zhang.[56] Coming across newly translated Marxist literature by Thomas Kirkup, Karl Kautsky, and Marx and Engels—notably The Communist Manifesto—he came under their increasing influence, but was still eclectic in his views.[57]

Mao visited Tianjin, Jinan, and Qufu,[58] before moving to Shanghai, where he worked as a laundryman and met Chen Duxiu, noting that Chen's adoption of Marxism "deeply impressed me at what was probably a critical period in my life". In Shanghai, Mao met an old teacher of his, Yi Peiji, a revolutionary and member of the Kuomintang (KMT), or Chinese Nationalist Party, which was gaining increasing support and influence. Yi introduced Mao to General Tan Yankai, a senior KMT member who held the loyalty of troops stationed along the Hunanese border with Guangdong. Tan was plotting to overthrow Zhang, and Mao aided him by organising the Changsha students. In June 1920, Tan led his troops into Changsha, and Zhang fled. In the subsequent reorganisation of the provincial administration, Mao was appointed headmaster of the junior section of the First Normal School. Now receiving a large income, he married Yang Kaihui, daughter of Yang Changji, in the winter of 1920.[59][60]

Founding the Chinese Communist Party: 1921–1922

The Chinese Communist Party was founded by Chen Duxiu and Li Dazhao in the Shanghai French Concession in 1921 as a study society and informal network. Mao set up a Changsha branch, also establishing a branch of the Socialist Youth Corps and a Cultural Book Society which opened a bookstore to propagate revolutionary literature throughout Hunan.[61] He was involved in the movement for Hunan autonomy, in the hope that a Hunanese constitution would increase civil liberties and make his revolutionary activity easier. When the movement was successful in establishing provincial autonomy under a new warlord, Mao forgot his involvement.[62][clarification needed] By 1921, small Marxist groups existed in Shanghai, Beijing, Changsha, Wuhan, Guangzhou, and Jinan; it was decided to hold a central meeting, which began in Shanghai on 23 July 1921. The first session of the National Congress of the Chinese Communist Party was attended by 13 delegates, Mao included. After the authorities sent a police spy to the congress, the delegates moved to a boat on South Lake near Jiaxing, in Zhejiang, to escape detection. Although Soviet and Comintern delegates attended, the first congress ignored Lenin's advice to accept a temporary alliance between the Communists and the "bourgeois democrats" who also advocated national revolution; instead they stuck to the orthodox Marxist belief that only the urban proletariat could lead a socialist revolution.[63]

Mao was party secretary for Hunan stationed in Changsha, and to build the party there he followed a variety of tactics.[64] In August 1921, he founded the Self-Study University, through which readers could gain access to revolutionary literature, housed in the premises of the Society for the Study of Wang Fuzhi, a Qing dynasty Hunanese philosopher who had resisted the Manchus.[64] He joined the YMCA Mass Education Movement to fight illiteracy, though he edited the textbooks to include radical sentiments.[65] He continued organising workers to strike against the administration of Hunan Governor Zhao Hengti.[66] Yet labour issues remained central. The successful and famous Anyuan coal mines strikes (contrary to later Party historians) depended on both "proletarian" and "bourgeois" strategies. Liu Shaoqi and Li Lisan and Mao not only mobilised the miners, but formed schools and cooperatives and engaged local intellectuals, gentry, military officers, merchants, Red Gang dragon heads and even church clergy.[67] Mao's labour organizing work in the Anyuan mines also involved his wife Yang Kaihui, who worked for women's rights, including literacy and educational issues, in the nearby peasant communities.[68] Although Mao and Yang were not the originators of this political organizing method of combining labor organizing among male workers with a focus on women's rights issues in their communities, they were among the most effective at using this method.[68] Mao's political organizing success in the Anyuan mines resulted in Chen Duxiu inviting him to become a member of the Communist Party's Central Committee.[69]

Mao claimed that he missed the July 1922 Second Congress of the Communist Party in Shanghai because he lost the address. Adopting Lenin's advice, the delegates agreed to an alliance with the "bourgeois democrats" of the KMT for the good of the "national revolution". Communist Party members joined the KMT, hoping to push its politics leftward.[70] Mao enthusiastically agreed with this decision, arguing for an alliance across China's socio-economic classes, and eventually rose to become propaganda chief of the KMT.[60] Mao was a vocal anti-imperialist and in his writings he lambasted the governments of Japan, the UK and US, describing the latter as "the most murderous of hangmen".[71]

Collaboration with the Kuomintang: 1922–1927

At the Third Congress of the Communist Party in Shanghai in June 1923, the delegates reaffirmed their commitment to working with the KMT. Supporting this position, Mao was elected to the Party Committee, taking up residence in Shanghai.[72] At the First KMT Congress, held in Guangzhou in early 1924, Mao was elected an alternate member of the KMT Central Executive Committee, and put forward four resolutions to decentralise power to urban and rural bureaus. His enthusiastic support for the KMT earned him the suspicion of Li Li-san, his Hunan comrade.[73]

In late 1924, Mao returned to Shaoshan, perhaps to recuperate from an illness. He found that the peasantry were increasingly restless and some had seized land from wealthy landowners to found communes. This convinced him of the revolutionary potential of the peasantry, an idea advocated by the KMT leftists but not the Communists.[74] Mao and many of his colleagues also proposed the end of cooperation with the KMT, which was rejected by the Comintern representative Mikhail Borodin.[75] In the winter of 1925, Mao fled to Guangzhou after his revolutionary activities attracted the attention of Zhao's regional authorities.[76] There, he ran the 6th term of the KMT's Peasant Movement Training Institute from May to September 1926.[77][78] The Peasant Movement Training Institute under Mao trained cadre and prepared them for militant activity, taking them through military training exercises and getting them to study basic left-wing texts.[79]

When party leader Sun Yat-sen died in May 1925, he was succeeded by Chiang Kai-shek, who moved to marginalise the left-KMT and the Communists.[80] Mao nevertheless supported Chiang's National Revolutionary Army, who embarked on the Northern Expedition attack in 1926 on warlords.[81] In the wake of this expedition, peasants rose up, appropriating the land of the wealthy landowners, who were in many cases killed. Such uprisings angered senior KMT figures, who were themselves landowners, emphasising the growing class and ideological divide within the revolutionary movement.[82]

In March 1927, Mao appeared at the Third Plenum of the KMT Central Executive Committee in Wuhan, which sought to strip General Chiang of his power by appointing Wang Jingwei leader. There, Mao played an active role in the discussions regarding the peasant issue, defending a set of "Regulations for the Repression of Local Bullies and Bad Gentry", which advocated the death penalty or life imprisonment for anyone found guilty of counter-revolutionary activity, arguing that in a revolutionary situation, "peaceful methods cannot suffice".[83][84] In April 1927, Mao was appointed to the KMT's five-member Central Land Committee, urging peasants to refuse to pay rent. Mao led another group to put together a "Draft Resolution on the Land Question", which called for the confiscation of land belonging to "local bullies and bad gentry, corrupt officials, militarists and all counter-revolutionary elements in the villages". Proceeding to carry out a "Land Survey", he stated that anyone owning over 30 mou (four and a half acres), constituting 13% of the population, were uniformly counter-revolutionary. He accepted that there was great variation in revolutionary enthusiasm across the country, and that a flexible policy of land redistribution was necessary.[85] Presenting his conclusions at the Enlarged Land Committee meeting, many expressed reservations, some believing that it went too far, and others not far enough. Ultimately, his suggestions were only partially implemented.[86]

Civil War

Nanchang and Autumn Harvest Uprisings: 1927

Fresh from the success of the Northern Expedition against the warlords, Chiang turned on the Communists, who by now numbered in the tens of thousands across China. Chiang ignored the orders of the Wuhan-based left KMT government and marched on Shanghai, a city controlled by Communist militias. As the Communists awaited Chiang's arrival, he loosed the White Terror, massacring 5,000 with the aid of the Green Gang.[84][87] In Beijing, 19 leading Communists were killed by Zhang Zuolin.[88][89] That May, tens of thousands of Communists and those suspected of being communists were killed, and the CCP lost approximately 15,000 of its 25,000 members.[89]

The CCP continued supporting the Wuhan KMT government, a position Mao initially supported,[89] but by the time of the CCP's Fifth Congress he had changed his mind, deciding to stake all hope on the peasant militia.[90] The question was rendered moot when the Wuhan government expelled all Communists from the KMT on 15 July.[90] The CCP founded the Workers' and Peasants' Red Army of China, better known as the "Red Army", to battle Chiang. A battalion led by General Zhu De was ordered to take the city of Nanchang on 1 August 1927, in what became known as the Nanchang Uprising. They were initially successful, but were forced into retreat after five days, marching south to Shantou, and from there they were driven into the wilderness of Fujian.[90] Mao was appointed commander-in-chief of the Red Army and led four regiments against Changsha in the Autumn Harvest Uprising, in the hope of sparking peasant uprisings across Hunan. On the eve of the attack, Mao composed a poem—the earliest of his to survive—titled "Changsha". His plan was to attack the KMT-held city from three directions on 9 September, but the Fourth Regiment deserted to the KMT cause, attacking the Third Regiment. Mao's army made it to Changsha, but could not take it; by 15 September, he accepted defeat and with 1000 survivors marched east to the Jinggang Mountains of Jiangxi.[91]

Base in Jinggangshan: 1927–1928

革命不是請客吃飯,不是做文章,不是繪畫繡花,不能那樣雅緻,那樣從容不迫,文質彬彬,那樣溫良恭讓。革命是暴動,是一個階級推翻一個階級的暴烈的行動。

Revolution is not a dinner party, nor an essay, nor a painting, nor a piece of embroidery; it cannot be so refined, so leisurely and gentle, so temperate, kind, courteous, restrained and magnanimous. A revolution is an insurrection, an act of violence by which one class overthrows another.

— Mao, February 1927[92]

The CCP Central Committee, hiding in Shanghai, expelled Mao from their ranks and from the Hunan Provincial Committee, as punishment for his "military opportunism", for his focus on rural activity, and for being too lenient with "bad gentry". The more orthodox Communists especially regarded the peasants as backward and ridiculed Mao's idea of mobilizing them.[60] They nevertheless adopted three policies he had long championed: the immediate formation of workers' councils, the confiscation of all land without exemption, and the rejection of the KMT. Mao's response was to ignore them.[93] He established a base in Jinggangshan City, an area of the Jinggang Mountains, where he united five villages as a self-governing state, and supported the confiscation of land from rich landlords, who were "re-educated" and sometimes executed. He ensured that no massacres took place in the region, and pursued a more lenient approach than that advocated by the Central Committee.[94] In addition to land redistribution, Mao promoted literacy and non-hierarchical organizational relationships in Jinggangshan, transforming the area's social and economic life and attracted many local supporters.[95]

Mao proclaimed that "Even the lame, the deaf and the blind could all come in useful for the revolutionary struggle", he boosted the army's numbers,[96] incorporating two groups of bandits into his army, building a force of around 1,800 troops.[97] He laid down rules for his soldiers: prompt obedience to orders, all confiscations were to be turned over to the government, and nothing was to be confiscated from poorer peasants. In doing so, he moulded his men into a disciplined, efficient fighting force.[96]

敵進我退,

敵駐我騷,

敵疲我打,

敵退我追。

When the enemy advances, we retreat.

When the enemy rests, we harass him.

When the enemy avoids a battle, we attack.

When the enemy retreats, we advance.

In spring 1928, the Central Committee ordered Mao's troops to southern Hunan, hoping to spark peasant uprisings. Mao was skeptical, but complied. They reached Hunan, where they were attacked by the KMT and fled after heavy losses. Meanwhile, KMT troops had invaded Jinggangshan, leaving them without a base.[100] Wandering the countryside, Mao's forces came across a CCP regiment led by General Zhu De and Lin Biao; they united, and attempted to retake Jinggangshan. They were initially successful, but the KMT counter-attacked, and pushed the CCP back; over the next few weeks, they fought an entrenched guerrilla war in the mountains.[98][101] The Central Committee again ordered Mao to march to south Hunan, but he refused, and remained at his base. Contrastingly, Zhu complied, and led his armies away. Mao's troops fended the KMT off for 25 days while he left the camp at night to find reinforcements. He reunited with the decimated Zhu's army, and together they returned to Jinggangshan and retook the base. There they were joined by a defecting KMT regiment and Peng Dehuai's Fifth Red Army. In the mountainous area they were unable to grow enough crops to feed everyone, leading to food shortages throughout the winter.[102]

In 1928, Mao met and married He Zizhen, an 18-year-old revolutionary who would bear him six children.[103][104]

Jiangxi Soviet Republic of China: 1929–1934

In January 1929, Mao and Zhu evacuated the base with 2,000 men and a further 800 provided by Peng, and took their armies south, to the area around Tonggu and Xinfeng in Jiangxi.[105] The evacuation led to a drop in morale, and many troops became disobedient and began thieving; this worried Li Lisan and the Central Committee, who saw Mao's army as lumpenproletariat, that were unable to share in proletariat class consciousness.[106][107] In keeping with orthodox Marxist thought, Li believed that only the urban proletariat could lead a successful revolution, and saw little need for Mao's peasant guerrillas; he ordered Mao to disband his army into units to be sent out to spread the revolutionary message. Mao replied that while he concurred with Li's theoretical position, he would not disband his army nor abandon his base.[107][108] Both Li and Mao saw the Chinese revolution as the key to world revolution, believing that a CCP victory would spark the overthrow of global imperialism and capitalism. In this, they disagreed with the official line of the Soviet government and Comintern. Officials in Moscow desired greater control over the CCP and removed Li from power by calling him to Russia for an inquest into his errors.[109] They replaced him with Soviet-educated Chinese Communists, known as the "28 Bolsheviks", two of whom, Bo Gu and Zhang Wentian, took control of the Central Committee. Mao disagreed with the new leadership, believing they grasped little of the Chinese situation, and he soon emerged as their key rival.[110][111]

In February 1930, Mao created the Southwest Jiangxi Provincial Soviet Government in the region under his control.[112] In November, he suffered emotional trauma after his second wife Yang Kaihui and sister were captured and beheaded by KMT general He Jian.[113] Facing internal problems, members of the Jiangxi Soviet accused him of being too moderate, and hence anti-revolutionary. In December, they tried to overthrow Mao, resulting in the Futian incident, during which Mao's loyalists tortured many and executed between 2000 and 3000 dissenters.[114] The CCP Central Committee moved to Jiangxi which it saw as a secure area. In November, it proclaimed Jiangxi to be the Soviet Republic of China, an independent Communist-governed state. Although he was proclaimed Chairman of the Council of People's Commissars, Mao's power was diminished, as his control of the Red Army was allocated to Zhou Enlai. Meanwhile, Mao recovered from tuberculosis.[115]

The KMT armies adopted a policy of encirclement and annihilation of the Red armies. Outnumbered, Mao responded with guerrilla tactics influenced by the works of ancient military strategists like Sun Tzu, but Zhou and the new leadership followed a policy of open confrontation and conventional warfare. In doing so, the Red Army successfully defeated the first and second encirclements.[116][117] Angered at his armies' failure, Chiang Kai-shek personally arrived to lead the operation. He too faced setbacks and retreated to deal with the further Japanese incursions into China.[118] As a result of the KMT's change of focus to the defence of China against Japanese expansionism, the Red Army was able to expand its area of control, eventually encompassing a population of 3 million.[117] Mao proceeded with his land reform program. In November 1931 he announced the start of a "land verification project" which was expanded in June 1933. He also orchestrated education programs and implemented measures to increase female political participation.[119] Chiang viewed the Communists as a greater threat than the Japanese and returned to Jiangxi, where he initiated the fifth encirclement campaign, which involved the construction of a concrete and barbed wire "wall of fire" around the state, which was accompanied by aerial bombardment, to which Zhou's tactics proved ineffective. Trapped inside, morale among the Red Army dropped as food and medicine became scarce. The leadership decided to evacuate.[120]

Long March: 1934–1935

On 14 October 1934, the Red Army broke through the KMT line on the Jiangxi Soviet's south-west corner at Xinfeng with 85,000 soldiers and 15,000 party cadres and embarked on the "Long March". In order to make the escape, many of the wounded and the ill, as well as women and children, were left behind, defended by a group of guerrilla fighters whom the KMT massacred.[121] The 100,000 who escaped headed to southern Hunan, first crossing the Xiang River after heavy fighting,[122] and then the Wu River, in Guizhou where they took Zunyi in January 1935. Temporarily resting in the city, they held a conference; here, Mao was elected to a position of leadership, becoming Chairman of the Politburo, and de facto leader of both Party and Red Army, in part because his candidacy was supported by Soviet Premier Joseph Stalin. Insisting that they operate as a guerrilla force, he laid out a destination: the Shenshi Soviet in Shaanxi, Northern China, from where the Communists could focus on fighting the Japanese. Mao believed that in focusing on the anti-imperialist struggle, the Communists would earn the trust of the Chinese people, who in turn would renounce the KMT.[123]

From Zunyi, Mao led his troops to Loushan Pass, where they faced armed opposition but successfully crossed the river. Chiang flew into the area to lead his armies against Mao, but the Communists outmanoeuvred him and crossed the Jinsha River.[124] Faced with the more difficult task of crossing the Tatu River, they managed it by fighting a battle over the Luding Bridge in May, taking Luding.[125] In Moukung, Western Sichuan, they encountered the 50,000-strong CCP Fourth Front Army of Zhang Guotao (who had marched from the mountain ranges around Ma'anshan[126]), and together proceeded to Maoerhkai and then Gansu. Zhang and Mao disagreed over what to do; the latter wished to proceed to Shaanxi, while Zhang wanted to retreat west to Tibet or Sikkim, far from the KMT threat. It was agreed that they would go their separate ways, with Zhu De joining Zhang.[127] Mao's forces proceeded north, through hundreds of kilometres of grasslands, an area of quagmire where they were attacked by Manchu tribesman and where many soldiers succumbed to famine and disease.[128] Finally reaching Shaanxi, they fought off both the KMT and an Islamic cavalry militia before crossing the Min Mountains and Mount Liupan and reaching the Shenshi Soviet; only 7,000–8,000 had survived.[129] The Long March cemented Mao's status as the dominant figure in the party. In November 1935, he was named chairman of the Military Commission. From this point onward, Mao was the Communist Party's undisputed leader, even though he would not become party chairman until 1943.[130]

World War II

Mao's troops arrived at the Yan'an Soviet during October 1935 and settled in Bao'an, until spring 1936. While there, they developed links with local communities, redistributed and farmed the land, offered medical treatment, and began literacy programs.[131] Mao now commanded 15,000 soldiers, boosted by the arrival of He Long's men from Hunan and the armies of Zhu De and Zhang Guotao returned from Tibet.[132] In February 1936, they established the North West Anti-Japanese Red Army University in Yan'an, through which they trained increasing numbers of new recruits.[133] In January 1937, they began the "anti-Japanese expedition", that sent groups of guerrilla fighters into Japanese-controlled territory to undertake sporadic attacks.[134] In May 1937, a Communist Conference was held in Yan'an to discuss the situation.[135] Western reporters also arrived in the "Border Region" (as the Soviet had been renamed); most notable were Edgar Snow, who used his experiences as a basis for Red Star Over China, and Agnes Smedley, whose accounts brought international attention to Mao's cause.[136]

On the Long March, Mao's wife He Zizhen had been injured by a shrapnel wound to the head. She travelled to Moscow for medical treatment; Mao proceeded to divorce her and marry an actress, Jiang Qing.[137][138] He Zizhen was reportedly "dispatched to a mental asylum in Moscow to make room" for Qing.[139] Mao moved into a cave-house and spent much of his time reading, tending his garden and theorising.[140] He came to believe that the Red Army alone was unable to defeat the Japanese, and that a Communist-led "government of national defence" should be formed with the KMT and other "bourgeois nationalist" elements to achieve this goal.[141] Although despising Chiang Kai-shek as a "traitor to the nation",[142] on 5 May, he telegrammed the Military Council of the Nanjing National Government proposing a military alliance, a course of action advocated by Stalin.[143] Although Chiang intended to ignore Mao's message and continue the civil war, he was arrested by one of his own generals, Zhang Xueliang, in Xi'an, leading to the Xi'an Incident; Zhang forced Chiang to discuss the issue with the Communists, resulting in the formation of a United Front with concessions on both sides on 25 December 1937.[144]

The Japanese had taken both Shanghai and Nanjing—resulting in the Nanjing Massacre, an atrocity Mao never spoke of all his life—and was pushing the Kuomintang government inland to Chongqing.[145] The Japanese's brutality led to increasing numbers of Chinese joining the fight, and the Red Army grew from 50,000 to 500,000.[146][147] In August 1938, the Red Army formed the New Fourth Army and the Eighth Route Army, which were nominally under the command of Chiang's National Revolutionary Army.[148] In August 1940, the Red Army initiated the Hundred Regiments Offensive, in which 400,000 troops attacked the Japanese simultaneously in five provinces. It was a military success that resulted in the death of 20,000 Japanese, the disruption of railways and the loss of a coal mine.[147][149] From his base in Yan'an, Mao authored several texts for his troops, including Philosophy of Revolution, which offered an introduction to the Marxist theory of knowledge; Protracted Warfare, which dealt with guerrilla and mobile military tactics; and On New Democracy, which laid forward ideas for China's future.[150]

In 1944, the U.S. sent a special diplomatic envoy, called the Dixie Mission, to the Chinese Communist Party. The American soldiers who were sent to the mission were favourably impressed. The party seemed less corrupt, more unified, and more vigorous in its resistance to Japan than the Kuomintang. The soldiers confirmed to their superiors that the party was both strong and popular over a broad area.[151] In the end of the mission, the contacts which the U.S. developed with the Chinese Communist Party led to very little.[151] After the end of World War II, the U.S. continued their diplomatic and military assistance to Chiang Kai-shek and his KMT government forces against the People's Liberation Army (PLA) led by Mao Zedong during the civil war and abandoned the idea of a coalition government which would include the CCP.[152] Likewise, the Soviet Union gave support to Mao by occupying north-eastern China, and secretly giving it to the Chinese communists in March 1946.[153]

Leadership of China

Establishment of the People's Republic of China

In 1948, the People's Liberation Army starved out the Kuomintang forces occupying Changchun. At least 160,000 civilians are believed to have perished during the siege, which lasted from June until October. PLA lieutenant colonel Zhang Zhenglu, in his book White Snow, Red Blood, compared it to Hiroshima: "The casualties were about the same. Hiroshima took nine seconds; Changchun took five months."[154] On 21 January 1949, Kuomintang forces suffered great losses in decisive battles against Mao's forces.[155] In the early morning of 10 December 1949, PLA troops laid siege to Chongqing and Chengdu on mainland China, and Chiang Kai-shek fled from the mainland to Taiwan.[155][156]

Mao proclaimed the establishment of the People's Republic of China from the Gate of Heavenly Peace (Tian'anmen) on 1 October 1949, and later that week declared "The Chinese people have stood up" (中国人民从此站起来了).[157] Mao went to Moscow for talks in the winter of 1949–50. Mao initiated the talks which focused on the political and economic revolution in China, foreign policy, railways, naval bases, and Soviet economic and technical aid. The resulting treaty reflected Stalin's dominance and his willingness to help Mao.[158][159]

Following the Marxist-Leninist theory of vanguardism,[160] Mao believed that only the correct leadership of the Communist Party could advance China into socialism.[160] Conversely, Mao also believed that mass movements and mass criticism were necessary in order to check the bureaucracy.[160]

Korean War

Mao pushed the Party to organise campaigns to reform society and extend control. These campaigns were given urgency in October 1950, when the People's Volunteer Army was sent into the Korean War and fight as well as to reinforce the armed forces of North Korea, the Korean People's Army, which had been in full retreat. The United States placed a trade embargo on the People's Republic as a result of its involvement in the Korean War, lasting until Richard Nixon's improvements of relations. At least 180,000 Chinese troops died during the war.[161]

As the Chairman of the Central Military Commission (CMC), he was also the Supreme Commander in Chief of the PLA and the People's Republic and Chairman of the Party. Chinese troops in Korea were under the overall command of then newly installed Premier Zhou Enlai, with General Peng Dehuai as field commander and political commissar.[162]

Social reform

During the land reform campaigns, large numbers of landlords and rich peasants were beaten to death at mass meetings as land was taken from them and given to poorer peasants, which reduced economic inequality.[163][164] The Campaign to Suppress Counter-revolutionaries[165] targeted bureaucratic bourgeoisie, such as compradors, merchants and Kuomintang officials who were seen by the party as economic parasites or political enemies.[166] In 1976, the U.S. State Department estimated as many as a million were killed in the land reform, and 800,000 killed in the counter-revolutionary campaign.[167]

Mao himself claimed that a total of 700,000 people were killed in attacks on "counter-revolutionaries" during the years 1950–1952.[168] Because there was a policy to select "at least one landlord, and usually several, in virtually every village for public execution",[169] the number of deaths range between 2 million[169][170][165] and 5 million.[171][172] In addition, at least 1.5 million people,[173] perhaps as many as 4 to 6 million,[174] were sent to "reform through labour" camps where many perished.[174] Mao played a personal role in organising the mass repressions and established a system of execution quotas,[175] which were often exceeded.[165] He defended these killings as necessary for the securing of power.[176]

The government is credited with eradicating both consumption and production of opium during the 1950s.[177][178] Ten million addicts were forced into compulsory treatment, dealers were executed, and opium-producing regions were planted with new crops. Remaining opium production shifted south of the Chinese border into the Golden Triangle region.[178]

Three-anti and Five-anti Campaigns

Starting in 1951, Mao initiated movements to rid urban areas of corruption, the Three-anti and Five-anti Campaigns. Whereas the three-anti campaign was a focused purge of government, industrial and party officials, the five-anti campaign set its sights slightly broader, targeting capitalist elements in general.[179] Workers denounced their bosses, spouses turned on their spouses, and children informed on their parents; the victims were often humiliated at struggle sessions, where a targeted person would be verbally and physically abused until they confessed to crimes. Mao insisted that minor offenders be criticised and reformed or sent to labour camps, "while the worst among them should be shot". These campaigns took several hundred thousand additional lives, the vast majority via suicide.[180]

In Shanghai, suicide by jumping from tall buildings became so commonplace that residents avoided walking on the pavement near skyscrapers for fear that suicides might land on them.[181] Some biographers have pointed out that driving those perceived as enemies to suicide was a common tactic during the Mao-era. In his biography of Mao, Philip Short notes that Mao gave explicit instructions in the Yan'an Rectification Movement that "no cadre is to be killed" but in practice allowed security chief Kang Sheng to drive opponents to suicide and that "this pattern was repeated throughout his leadership of the People's Republic".[182]

Five-year plans

Following the consolidation of power, Mao launched the first five-year plan (1953–1958), which emphasised rapid industrial development. Within industry, iron and steel, electric power, coal, heavy engineering, building materials, and basic chemicals were prioritised with the aim of constructing large and highly capital-intensive plants. Many of these plants were built with Soviet assistance and heavy industry grew rapidly.[183] Agriculture, industry and trade was organised as worker cooperatives.[184] This period marked the beginning of China's rapid industrialisation and it resulted in an enormous success.[185]

Despite being initially sympathetic towards the reformist government of Imre Nagy, Mao feared the "reactionary restoration" in Hungary as the Hungarian Revolution of 1956 continued and became more hardline. Mao opposed the withdrawal of Soviet troops by asking Liu Shaoqi to inform the Soviet representatives to use military intervention against "Western imperialist-backed" protestors and Nagy's government. However, it was unclear to what degree Mao's stance played a role in Nikita Khrushchev's decision to invade Hungary. It was also unclear if China was forced to conform to the Soviet position due to economic concerns and China's poor power projections compared to the USSR. Despite his disagreements with Moscow's hegemony in the Eastern Bloc, Mao viewed the integrity of the international communist movement as more important than the national autonomy of the countries in the Soviet sphere of influence. The Hungarian crisis also influenced Mao's Hundred Flowers Campaign. Mao decided to soften his stance on Chinese intelligentsia and allow them to express their social dissatisfaction and criticisms of the errors of the government. Mao wanted to use this movement to prevent a similar uprising in China. However, as people in China began to criticize the CCP's policies and Mao's leadership following the Hundred Flowers Campaign, Mao cracked down the movement he initiated and compared it to the "counter-revolutionary" Hungarian Revolution.[186]

During the Hundred Flowers Campaign, Mao indicated his supposed willingness to consider different opinions about how China should be governed. Given the freedom to express themselves, liberal and intellectual Chinese began opposing the Communist Party and questioning its leadership. This was initially tolerated and encouraged. After a few months, Mao's government reversed its policy and persecuted those who had criticised the party, totalling perhaps 500,000,[187] as well as those who were merely alleged to have been critical, in what is called the Anti-Rightist Movement. The movement led to the persecution of at least 550,000 people, mostly intellectuals and dissidents.[188] Li Zhisui, Mao's physician, suggested that Mao had initially seen the policy as a way of weakening opposition to him within the party and that he was surprised by the extent of criticism and the fact that it came to be directed at his own leadership.[189]

Military projects

United States President Dwight D. Eisenhower's threats during the First Taiwan Strait Crisis to use nuclear weapons against military targets in Fujian province prompted Mao to begin China's nuclear program.[190]: 89–90 Under Mao's Two Bombs, One Satellite program, China developed the atomic and hydrogen bombs in record time[quantify] and launched a satellite a few years after the Soviet Union launched Sputnik.[191]: 218

Project 523[192] is a 1967 military project to find antimalarial medications.[193] It addressed malaria, an important threat in the Vietnam War. Zhou Enlai convinced Mao Zedong to start the mass project "to keep [the] allies' troops combat-ready", as the meeting minutes put it. The one for investigating traditional Chinese medicine discovered and led to the development of a class of new antimalarial drugs called artemisinins.[194]

Great Leap Forward

In January 1958, Mao launched the Great Leap Forward, to turn China from an agrarian nation to an industrialised one.[195] The relatively small agricultural collectives that had been formed were merged into far larger people's communes, and many peasants were ordered to work on infrastructure projects and on the production of iron and steel. Some private food production was banned, and livestock and farm implements were brought under collective ownership.[196]

The effect of the diversion of labour to steel production and infrastructure projects, and cyclical natural disasters led to an approximately 15% drop in grain production in 1959 followed by a further 10% decline in 1960 and no recovery in 1961.[197]

To win favour with their superiors and avoid being purged, each layer in the party exaggerated the amount of grain produced under them. Based upon the falsely reported success, party cadres were ordered to requisition a high amount of that fictitious harvest. The result, compounded in some areas by drought and in others by floods, was that farmers were left with little food and many millions starved to death in the Great Chinese Famine. The people of urban areas were given food stamps each month, but the people of rural areas were expected to grow their own crops and give some of the crops back to the government. The death count in rural parts of China surpassed the deaths in the urban centers.[198] The famine was a direct cause of the death of some 30 million Chinese peasants between 1959 and 1962.[199] Many children became malnourished.[197]

In late autumn 1958, Mao condemned the practices used during Great Leap Forward such as forcing peasants to do labour without enough food or rest which resulted in epidemics and starvation. He also acknowledged that anti-rightist campaigns were a major cause of "production at the expense of livelihood." He refused to abandon the Great Leap Forward, but he did demand that they be confronted. After the July 1959 clash at Lushan Conference with Peng Dehuai, Mao launched a new anti-rightist campaign along with the radical policies that he previously abandoned. It wasn't until the spring of 1960, that Mao would again express concern about abnormal deaths and other abuses, but he did not move to stop them. Bernstein concludes that the Chairman "wilfully ignored the lessons of the first radical phase for the sake of achieving extreme ideological and developmental goals".[200]

Mao stepped down as President of China on 27 April 1959; he retained other top positions such as Chairman of the Communist Party and of the Central Military Commission.[201] The Presidency was transferred to Liu Shaoqi.[201] Mao eventually abandoned the policy in 1962.[202] Liu Shaoqi and Deng Xiaoping rescued the economy by disbanding the people's communes, introducing elements of private control of peasant smallholdings and importing grain from Canada and Australia to mitigate the worst effects of famine.[203]

At the Lushan Conference in July/August 1959, several ministers expressed concern that the Great Leap Forward had not proved as successful as planned. The most direct of these was Minister of Defence Peng Dehuai. Following Peng's criticism of the Great Leap Forward, Mao made a purge of Peng and his supporters, stifling criticism of the Great Leap policies. A campaign was launched and resulted in party members and ordinary peasants being sent to prison labour camps. Years later the CCP would conclude that as many as six million people were wrongly punished in the campaign.[204]

Split from Soviet Union

The Sino-Soviet split resulted in Nikita Khrushchev's withdrawal of Soviet technical experts and aid from the country. The split concerned the leadership of world communism. The USSR had a network of Communist parties it supported; China now created its own rival network to battle it out.[205] Lorenz M. Lüthi writes: "The Sino-Soviet split was one of the key events of the Cold War, equal in importance to the construction of the Berlin Wall, the Cuban Missile Crisis, the Second Vietnam War, and Sino-American rapprochement. The split helped to determine the framework of the Second Cold War in general, and influenced the course of the Second Vietnam War in particular."[206]

The split resulted from Khrushchev's more moderate Soviet leadership after the death of Stalin in March 1953. Only Albania openly sided with China, thereby forming an alliance between the two countries. Warned that the Soviets had nuclear weapons, Mao minimised the threat.[207] Struggle against Soviet revisionism and U.S. imperialism was an important aspect of Mao's attempt to direct the revolution in the right direction.[208]

In the late 1950s, Mao wrote reading notes responding to the Soviet Book Political Economy: A Textbook and essays (A Critique of Soviet Economics) responding to Stalin's Economic Problems of Socialism in the USSR.[209]: 51 These texts reflect Mao's views that the USSR was becoming alienated from the masses and distorting socialist development.[209]: 51

Third Front

After the Great Leap Forward, China's leadership slowed the pace of industrialization.[210]: 3 It invested more on in China's coastal regions and focused on the production of consumer goods.[210]: 3 Preliminary drafts of the Third Five Year Plan contained no provision for developing large scale industry in China's interior.[210]: 29 After an April 1964 General Staff report concluded that the concentration of China's industry in its major coastal cities made it vulnerable to attack by foreign powers, Mao argued for the development of basic industry and national defense industry in protected locations in China's interior.[210]: 4, 54 Although other key leaders did not initially support the idea, the 2 August 1964 Gulf of Tonkin incident increased fears of a potential invasion by the United States and crystallized support for Mao's industrialization proposal, which came to be known as the Third Front.[210]: 7 Following the Gulf of Tonkin incident, Mao's own concerns of invasion by the United States increased.[211]: 100 He wrote to central cadres, "A war is going to break out. I need to reconsider my actions" and pushed even harder for the creation of the Third Front.[211]: 100

The secretive Third Front construction involved massive projects including extensive railroad infrastructure like the Chengdu–Kunming line,[210]: 153–164 aerospace industry including satellite launch facilities,[210]: 218–219 and steel production industry including Panzhihua Iron and Steel.[210]: 9

Development of the Third Front slowed in 1966, but accelerated again after the Sino-Soviet border conflict at Zhenbao Island, which increased the perceived risk of Soviet Invasion.[210]: 12, 150 Third Front construction again decreased after United States President Richard Nixon's 1972 visit to China and the resulting rapprochement between the United States and China.[210]: 225–229 When Reform and Opening up began after Mao's death, China began to gradually wind down Third Front projects.[212]: 180 The Third Front distributed physical and human capital around the country, ultimately decreased regional disparities and created favorable conditions for later market development.[212]: 177–182

Great Proletarian Cultural Revolution

During the early 1960s, Mao became concerned with the nature of post-1959 China. He saw that the old ruling elite was replaced by a new one. He was concerned that those in power were becoming estranged from the people they were to serve. Mao believed that a revolution of culture would unseat and unsettle the "ruling class" and keep China in a state of "continuous revolution" that, theoretically, would serve the interests of the majority, rather than a tiny and privileged elite.[213]

The Cultural Revolution led to the destruction of much of China's traditional cultural heritage and the imprisonment of many Chinese citizens, as well as the creation of chaos in the country. Millions of lives were ruined, as the Cultural Revolution pierced into Chinese life. It is estimated that hundreds of thousands of people, perhaps millions, perished in the violence of the Cultural Revolution.[214] This included prominent figures such as Liu Shaoqi.[215][216][217]

It was during this period that Mao chose Lin Biao to become his successor. Lin was later officially named as Mao's successor. By 1971, a divide between the two men had become apparent. Lin Biao died on 13 September 1971, in a plane crash over the air space of Mongolia, presumably as he fled China, probably anticipating his arrest. The CCP declared that Lin was planning to depose Mao and posthumously expelled Lin from the party. At this time, Mao lost trust in many of the top CCP figures. The highest-ranking Soviet Bloc intelligence defector, Lt. Gen. Ion Mihai Pacepa claimed he had a conversation with Nicolae Ceaușescu, who told him about a plot to kill Mao with the help of Lin Biao organised by the KGB.[218]

In 1969, Mao declared the Cultural Revolution to be over. Various historians mark the end of the Cultural Revolution in 1976, following Mao's death and the arrest of the Gang of Four.[219] The Central Committee in 1981 officially declared the Cultural Revolution a "severe setback" for the PRC.[220]

An estimate of around 400,000 deaths is a widely accepted minimum figure, according to Maurice Meisner.[221] MacFarquhar and Schoenhals assert that in rural China alone some 36 million people were persecuted, of whom between 750,000 and 1.5 million were killed, with roughly the same number permanently injured.[222]

State visits

| Country | Date | Host |

|---|---|---|

| 16 December 1949 | Joseph Stalin | |

| 2–19 November 1957 | Nikita Khrushchev |

During his leadership, Mao traveled outside China, which were state visits to the Soviet Union. His first visit abroad was in December 1949 to celebrate the 70th birthday of Joseph Stalin in Moscow, which was also attended by East German Deputy Chairman of the Council of Ministers Walter Ulbricht and Mongolian communist General Secretary Yumjaagiin Tsedenbal.[223] The second visit to Moscow in November 1957 was a two-week state visit of which the highlights included Mao's attendance at the 40th anniversary (Ruby Jubilee) celebrations of the October Revolution (he attended the annual military parade of the Moscow Garrison on Red Square as well as a banquet in the Moscow Kremlin) and the International Meeting of Communist and Workers Parties, where he met with other communist leaders.[224]

Death and aftermath

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Mao's health declined in his last years, probably aggravated by his chain-smoking.[225] It became a state secret that he suffered from multiple lung and heart ailments during his later years.[226] There are unconfirmed reports that he possibly had Parkinson's disease[227][228] in addition to amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ALS), also known as Lou Gehrig's disease.[229] He suffered two major heart attacks, one in March and another in July, then a third on 5 September, rendering him an invalid. He died nearly four days later, on 9 September 1976, at the age of 82. The Communist Party delayed the announcement of his death until 16:00, when a national radio broadcast announced the news and appealed for party unity.[228]

Mao's embalmed body, draped in the CCP flag, lay in state at the Great Hall of the People for one week.[230] One million Chinese filed past to pay their final respects, many displaying sadness, while foreigners watched on television.[231][232] Mao's official portrait hung on the wall with a banner reading: "Carry on the cause left by Chairman Mao and carry on the cause of proletarian revolution to the end".[230] On 17 September, the body was taken in a minibus to the 305 Hospital, where his internal organs were preserved in formaldehyde.[230]

On 18 September, guns, sirens, whistles and horns across China were simultaneously blown and a mandatory three-minute silence was observed.[233] Tiananmen Square was packed with millions of people and a military band played "The Internationale". Hua Guofeng concluded the service with a 20-minute-long eulogy atop Tiananmen Gate.[234] Despite Mao's request to be cremated, his body was later permanently put on display in the Mausoleum of Mao Zedong, in order for the Chinese nation to pay its respects.[235]

On 27 June 1981, the communist party's Central Committee adopted the Resolution on Certain Questions in the History of Our Party since the Founding of the People's Republic of China, which assessed the legacy of the Mao era and the party's priorities going forward.[236]: 166 The Resolution describes setbacks during the period 1957 to 1964 (although it generally affirms this period) and major mistakes beginning in 1965, attributing Mao's errors to individualist tendencies which arose when he departed from the collective view of the leadership.[236]: 167 Regarding Mao's legacy, the Resolution concludes Mao's contributions to the Chinese Revolution far outweigh his mistakes.[237]: 445

Legacy

Mao has been regarded as one of the most important and influential individuals in the 20th century.[238][239] He has also been described as a political intellect, theorist, military strategist, poet, and visionary.[240] He was credited and praised for driving imperialism out of China,[241] having unified China and for ending the previous decades of civil war. He has also been credited with having improved the status of women in China and for improving literacy and education.[177][242][243][244] In December 2013, a poll from the state-run Global Times indicated that roughly 85% of the 1,045 respondents surveyed felt that Mao's achievements outweighed his mistakes.[245] It has been said in China that Mao was 70 percent right and 30 percent wrong.[10]: 55 [237]: 445

His policies resulted in the deaths of tens of millions of people in China during his reign,[246][247][248] done through starvation, persecution, prison labour in laogai, and mass executions.[182][246] Mao rarely gave direct instruction for peoples' physical elimination.[249] According to Philip Short, the overwhelming majority of those killed by Mao's policies were unintended casualties of famine, while the other three or four million, in Mao's view, were necessary victims in the struggle to transform China.[250] Mao's China has been described as an autocratic and totalitarian regime responsible for mass repression.[251][252][253][254][255] Mao was accused as one of the great tyrants of the twentieth century.[256][257][182][246] He was frequently likened to the First Emperor of a unified China, Qin Shi Huang.[258][259][260][257][b]

China's population grew from around 550 million to over 900 million under his rule.[261][262] Mao's insurgency strategies continue to be used by insurgents, and his political ideology continues to be embraced by many Communist organisations around the world.[263]

In China

In mainland China, Mao is respected by a great number of the general population. Mao is credited for raising the average life expectancy from 35 in 1949 to 63 by 1975, bringing "unity and stability to a country that had been plagued by civil wars and foreign invasions", and laying the foundation for China to "become the equal of the great global powers".[264] He is lauded for carrying out massive land reform, promoting the status of women, improving popular literacy, and positively "transform(ing) Chinese society beyond recognition."[264] Mao has been credited for boosting literacy (only 20% of the population could read in 1949, compared to 65.5% thirty years later), doubling life expectancy, a near doubling of the population, and developing China's industry and infrastructure, paving the way for its position as a world power.[265][243][244]

Opposition to Mao can lead to censorship or professional repercussions in mainland China,[266] and is often done in private settings.[267] When a video of Bi Fujian, a television host, insulting Mao at a private dinner in 2015 went viral, Bi garnered the support of Weibo users, with 80% of them saying in a poll that Bi should not apologize amidst backlash from state affiliates.[268][269] Chinese citizens are aware of Mao's mistakes, but many see Mao as a national hero. He is seen as someone who successfully liberated the country from Japanese occupation and from Western imperialist exploitation dating back to the Opium Wars.[270] Between 2015 and 2018, The Washington Post interviewed 70 people in China about the Maoist era. A "sizable proportion" lauded the era's simplicity, attributing to it the "clear meaning" of life and minimal inequality; they contended that the "spiritual life" was rich. The interviewees simultaneously acknowledged the poor "material life" and other negative experiences under Mao.[270]

On 25 December 2008, China opened the Mao Zedong Square to visitors in his home town of central Hunan Province to mark the 115th anniversary of his birth.[271]

Former party official Su Shachi has opined that "he was a great historical criminal, but he was also a great force for good."[272] In a similar vein, journalist Liu Binyan has described Mao as "both monster and a genius."[272] Li Rui, Mao's personal secretary and Communist Party comrade, opined that "Mao's way of thinking and governing was terrifying. He put no value on human life. The deaths of others meant nothing to him."[273]

Chen Yun remarked "Had Mao died in 1956, his achievements would have been immortal. Had he died in 1966, he would still have been a great man but flawed. But he died in 1976. Alas, what can one say?"[274] Deng Xiaoping said "I should remind you that Chairman Mao dedicated most of his life to China, that he saved the party and the revolution in their most critical moments, that, in short, his contribution was so great that, without him, the Chinese people would have had a much harder time finding the right path out of the darkness. We also shouldn't forget that it was Chairman Mao who combined the teachings of Marx and Lenin with the realities of Chinese history—that it was he who applied those principles, creatively, not only to politics but to philosophy, art, literature, and military strategy."[275]

Outside China

| External videos | |

|---|---|

Philip Short said that the overwhelming majority of the deaths under Mao were unintended consequences of famine.[250] Short stated that landlord class were not exterminated as a people due to Mao's belief in redemption through thought reform,[250] and compared Mao with 19th-century Chinese reformers who challenged China's traditional beliefs in the era of China's clashes with Western colonial powers. Short writes that "Mao's tragedy and his grandeur were that he remained to the end in thrall to his own revolutionary dreams. ... He freed China from the straitjacket of its Confucian past, but the bright Red future he promised turned out to be a sterile purgatory."[250]

Alexander V. Pantsov and Steven I. Levine, in their biography, asserted that Mao was both "a successful creator and ultimately an evil destroyer" but also argued that he was a complicated figure who should not be lionised as a saint or reduced to a demon, as he "indeed tried his best to bring about prosperity and gain international respect for his country."[276] They also remarked on Mao's legacy: "A talented Chinese politician, an historian, a poet and philosopher, an all-powerful dictator and energetic organizer, a skillful diplomat and utopian socialist, the head of the most populous state, resting on his laurels, but at the same time an indefatigable revolutionary who sincerely attempted to refashion the way of life and consciousness of millions of people, a hero of national revolution and a bloody social reformer—this is how Mao goes down in history. The scale of his life was too grand to be reduced to a single meaning." Mao's English interpreter Sidney Rittenberg wrote in his memoir that whilst Mao "was a great leader in history", he was also "a great criminal because, not that he wanted to, not that he intended to, but in fact, his wild fantasies led to the deaths of tens of millions of people."[277]

The United States placed a trade embargo on the People's Republic as a result of its involvement in the Korean War, until Richard Nixon decided that developing relations with the PRC would be useful.[278] The television series Biography stated: "[Mao] turned China from a feudal backwater into one of the most powerful countries in the World. ... The Chinese system he overthrew was backward and corrupt; few would argue the fact that he dragged China into the 20th century. But at a cost in human lives that is staggering."[272] Professor Jeffrey Wasserstrom compares China's relationship to Mao to Americans' remembrance of Andrew Jackson; both countries regard the leaders in a positive light, despite their respective roles in devastating policies. Jackson forcibly moved Native Americans through the Trail of Tears, resulting in thousands of deaths, while Mao was at the helm.[279][c]

John King Fairbank remarked, "The simple facts of Mao's career seem incredible: in a vast land of 400 million people, at age 28, with a dozen others, to found a party and in the next fifty years to win power, organize, and remold the people and reshape the land—history records no greater achievement. Alexander, Caesar, Charlemagne, all the kings of Europe, Napoleon, Bismarck, Lenin—no predecessor can equal Mao Tse-tung's scope of accomplishment, for no other country was ever so ancient and so big as China."[280] In China: A New History, Fairbank and Goldman assessed Mao's legacy: "Future historians may conclude that Mao's role was to try to destroy the age-old bifurcation of China between a small educated ruling stratum and the vast mass of common people. We do not yet know how far he succeeded. The economy was developing, but it was left to his successors to create a new political structure."[281]

Stuart R. Schram said "Eternal rebel, refusing to be bound by the laws of God or man, nature or Marxism, he led his people for three decades in pursuit of a vision initially noble, which turned increasingly into a mirage, and then into a nightmare. Was he a Faust or Prometheus, attempting the impossible for the sake of humanity, or a despot of unbridled ambition, drunk with his own power and his own cleverness?"[282] Schram also said "I agree with the current Chinese view that Mao's merits outweighed his faults, but it is not easy to put a figure on the positive and negative aspects. How does one weigh, for example, the good fortune of hundreds of millions of peasants in getting land against the execution, in the course of land reform and the 'Campaign against Counter-Revolutionaries,' or in other contexts, of millions, some of whom certainly deserved to die, but others of whom undoubtedly did not? How does one balance the achievements in economic development during the first Five-Year Plan, or during the whole twenty-seven years of Mao's leadership after 1949, against the starvation which came in the wake of the misguided enthusiasm of the Great Leap Forward, or the bloody shambles of the Cultural Revolution?" Schram added, "In the last analysis, however, I am more interested in the potential future impact of his thought than in sending Mao as an individual to Heaven or to Hell."[283]