Australia Day debate

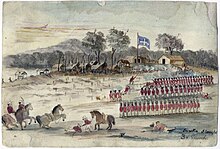

Australia Day is Australia's national day, marking the anniversary of Captain Arthur Phillip's First Fleet raising the British Union Jack at Sydney Cove in 1788. After the Federation of Australia on 1 January 1901, the official recognition and dates of Australia Day and its corresponding holidays emerged gradually and changed many times. Further alternations and alternatives have been proposed for debate, but not yet officially agreed or adopted.

Previously, Australia Day public holidays were held on different dates around Australia (such as a movable Monday or Friday for long weekends) with the first "Australia Day" being designated as Friday 30 July 1915 (as fundraising for World War I), and 26 January having been formerly recognised by different names (prior to 1946) as a regionally-specific date lacking national recognition (prior to 1935) and lacking official celebrations in the nation's own capital.[1][2][3][4][5][6][7]

There have also been proposals to institute a second day specifically for Indigenous Australians in addition to the existing date, which is often referred to as Invasion Day by opponents. Polling has shown a marked shift towards support for a change of date or second day of celebration since 2000, though around two thirds of respondents in recent years have supported the current date.[8] Various proposals for the name and date of a new holiday have been put forward.

Reasons for alternative dates

[edit]Both before the establishment of Australia Day as the national day of Australia, and in the years after its creation, several dates have been proposed for its celebration and, at various times, the possibility of moving Australia Day to an alternative date has been mooted. Some reasons put forward are that the current date, celebrating the foundation of the Colony of New South Wales, lacks national significance;[9] that the day falls during school holidays which limits the engagement of schoolchildren in the event;[9] and that it fails to encompass members of the Indigenous community and some others who perceive the day as commemorating the date of an invasion of their land.[9] Connected to this is the suggestion that moving the date would be seen as a significant symbolic act.[10]

Some Australians regard Australia Day as a symbol of the adverse impacts of British settlement on Australia's Indigenous peoples.[11]

In 1888, prior to the first centennial anniversary of the First Fleet landing on 26 January 1788, New South Wales premier Henry Parkes was asked about inclusion of Aboriginal people in the celebrations. He replied: "And remind them that we have robbed them?"[12]

Responses

[edit]Protests

[edit]

The celebrations in 1938 were accompanied by an Aboriginal Day of Mourning.[13] The Aboriginal Tent Embassy was established outside Old Parliament House, Canberra, on Australia Day in 1972, and celebrated 50 years of existence in 2022.[14]

A large gathering of Aboriginal people in Sydney in 1988 led an "Invasion Day" commemoration marking the loss of Indigenous culture.[13] Some Indigenous figures and others continue to label Australia Day as "Invasion Day", and protests occur almost every year, sometimes at Australia Day events.[15]

Thousands of people participate in protest marches in capital cities on Australia Day. Estimates for the 2018 protest in Melbourne ranged in the tens of thousands,[16][17][18][19] and around 80,000 in 2019, when rallies were also held across the country.[20]

Political responses

[edit]A move to change the date would have to be made by a combination of the Australian federal and state governments,[21] and has thus far lacked sufficient political and public support.

In 2001, Prime Minister John Howard stated that he acknowledged Aboriginal concerns with the date, but that it was nevertheless a significant day in Australia's history, and should therefore be retained.[22] In 2009, in response to Mick Dodson's suggestion to reopen the debate, prime minister Kevin Rudd refused to do so, and opposition leader Malcolm Turnbull agreed; however both supported the right of Australians to raise the issue. Also in that year, at state level, NSW premier Nathan Rees and Queensland premier Anna Bligh opposed a change.[23]

In 2018, prime minister Scott Morrison rejected moving Australia Day, proposing the addition of another day for Indigenous Australians instead. Frontbencher Ken Wyatt supported the proposal, suggesting establishing it on a day during NAIDOC Week in July.[24]

In January 2023, Queensland LNP MP Henry Pike drafted a bill that would keep Australia Day on 26 January.[25][26]

On Australia Day 2024, Prime Minister Anthony Albanese confirmed the date would not be changed any time soon. He did not suggest an alternative.

Local councils

[edit]In June 2017 the annual National General Assembly of the Australian Local Government Association voted by a slim majority for councils to consider how to lobby the federal government for a date change.[27] In August 2017 the council of the City of Yarra, in Melbourne, resolved unanimously that it would no longer hold citizenship ceremonies on 26 January and stop referring to it as Australia Day, instead holding an event acknowledging Aboriginal culture and history;[28] the City of Darebin soon followed suit. The federal government immediately deprived the councils of their powers to hold citizenship ceremonies.[29][30][31][32]

On 13 January 2019 prime minister Scott Morrison announced that, with effect from Australia Day 2020, all local councils would be required to hold citizenship ceremonies on and only on 26 January and 17 September.[33] The Inner West Council was the first local authority in Sydney to end Australia Day celebrations, from 2020,[34] while in February 2021 the City of Mitcham became the first local council in South Australia to officially oppose the date of Australia Day.[35]

Following the decision by Woolworths, Big W and Aldi not to stock extra items for Australia Day, Fairfield City Council in Sydney resolved to provide free Australia Day merchandise to residents.[36]

Commercial responses

[edit]In 2023, retail chain Kmart stopped selling Australia Day merchandise, as did Woolworths, Big W and Aldi in 2024,[37] with Woolworths citing a decline in demand and noting that it sells Australian flags all year round.[38] The decision by Woolworths caused some controversy, with opposition leader Peter Dutton calling for a boycott of Woolworths,[38] and vandalism to two stores in Brisbane.[39][40][41] The company's CEO noted that the company was not attempting to "cancel" the holiday.[42]

Other responses

[edit]Among those calling for change have been Tony Beddison, then chairman of the Australia Day Committee (Victoria), who argued for change and requested debate on the issue in 1999;[9] and Mick Dodson, Australian of the Year in 2009, who called for debate as to when Australia Day was held.[43]

In 2016, National Indigenous Television chose the name "Survival Day" as its preferred choice on the basis that it acknowledges the mixed nature of the day, saying that the term "recognises the invasion", but does not allow that to frame the entire story of the Aboriginal people.[44]

The anniversary is also termed by some as "Survival Day" and marked by events such as the Survival Day concert, first held in Sydney in 1992, celebrating the fact that the Indigenous people and culture have survived despite colonisation and discrimination.[45]

Suggested alternatives

[edit]Abolition

[edit]Some people call for the abolition of Australia Day altogether,[46][47][48] arguing that any day celebrating Australia celebrates colonisation and Indigenous genocide. Luke Pearson writes, “You want a day to celebrate Australia. I want an Australia that’s worth celebrating.”[49]

1 January (Federation of Australia)

[edit]

As early as 1957, 1 January was suggested as a possible alternative day, to commemorate the Federation of Australia.[50] In 1902, the year after Federation, 1 January was named "Commonwealth Day".[51] However, New Year's Day was already a public holiday, and Commonwealth Day did not gather much support.[51]

19 January (alternative federation date)

[edit]Proposed as an alternative because it is only one week earlier than Australia Day and "19/01" can represent the year of Federation.[52]

25 and 26 January (two national days)

[edit]The Two Australia Day campaign proposes that January 25 should be "First Australians Day" – a mourning for the last unspoiled day of Indigenous life – and that January 26 should be rebranded as "New Australians Day", a day to celebrate Australia's rich history of immigration.[53] This idea was first mooted by and activist Noel Pearson, as outlined in an essay published in the 2021 collection Mission.[54][page needed] Alan Kohler supported this proposal in his opinion piece published in The New Daily on 25 January 2023.[55]

3 March (Australia Act)

[edit]There has been support for an "independence day", 3 March, to represent the enacting of the Australia Act 1986.[56]

25 April (Anzac Day)

[edit]There has been a degree of support by some in recent years for making Anzac Day, 25 April, Australia's national day, including in 1999, by Anglican Archbishop of Brisbane Peter Hollingworth.[57][21] In 2001, following comments made during a review into the future of Anzac Day,[58] the idea of a merger was strongly opposed by Prime Minister John Howard and Opposition Leader Kim Beazley, who clarified his earlier position.[59]

8 May ("mate")

[edit]Starting 2017, there has been a partially humorous suggestion to move Australia Day to 8 May. This is primarily because of the homophonous quality between "May 8" and the Australian idiom "mate", but also because the opening of the first Federal Parliament was on 9 May.[60][61][62]

9 May (opening of Provisional Parliament House)

[edit]The date 9 May is also sometimes suggested, the date on which the first federal seat of parliament was opened in Melbourne in 1901, the date of the opening of the Provisional Parliament House in Canberra in 1927, and the date of the opening of the New Parliament House in 1988.[63] The date has, at various times, found support from former Queensland Premier Peter Beattie, Tony Beddison,[9] and Geoffrey Blainey.[64] However, the date has been seen by some as being too closely connected with Victoria,[65] and its location close to the start of winter has been described as an impediment.[63]

27 May (1967 referendum)

[edit]The anniversary of the 1967 referendum to amend the federal constitution has also been suggested.[10] The amendments enabled the federal parliament to legislate with regard to Indigenous Australians and allowed for Indigenous Australians to be included in the national census. The public vote in favour was 91%.

9 July (acceptance of the Constitution)

[edit]This is the date when Queen Victoria accepted the Constitution of Australia.[66]

1 September (Wattle Day)

[edit]Wattle Day is the first day of spring in the southern hemisphere. Australia's green and gold comes from the wattle, and it has symbolised Australia since the early 1800s. Wattle Day has been proposed as the new date for Australia Day since the 1990s and is supported by the National Wattle Day Association.[67][68]

8 September

[edit]This was the day Australia was first circumnavigated, by Matthew Flinders and Bungaree in 1803.[69]

17 September

[edit]On 17 September 1790, Governor Phillip decided not to punish Willemering despite being speared by him 10 days earlier, realising he had done so for kidnapping Bennelong, and met them with gifts which they accepted – some consider this to be the first of a series of relative friendship between the two groups.[70] Since 2001, this date is also considered Australian Citizenship Day,[71] and citizenship ceremonies are also held on that date as of 2020.[33]

24 October (Tenterfield Oration)

[edit]On 24 October 1889 Sir Henry Parkes, the "Father of Federation", gave his pivotal speech at Tenterfield in NSW, which set the course for federation.[72]

3 December (Eureka Stockade)

[edit]The Eureka Stockade on 3 December has had a long history as an alternative choice for Australia Day, having been proposed by The Bulletin in the 1880s.[73] The Eureka uprising occurred in 1854 during the Victorian gold rush, and saw a failed rebellion by the miners against the Victorian colonial government. Although the rebellion was crushed, it led to significant reforms, and has been described as being the birthplace of Australian democracy.[74] Supporters of the date have included senator Don Chipp and former Victorian Premier Steve Bracks.[9][75] However, the idea has been opposed by both hard-left unions and right-wing nationalist groups, both of whom claim symbolic attachment to the event,[74] and by some who see it as an essentially Victorian event.[65]

Polling

[edit]2000s

[edit]In 2004, a Newspoll poll that asked if the date of Australia Day should be moved to one that is not associated with European settlement found 79% of respondents favoured no change, 15% favoured change, and 6% were uncommitted.[76] Historian Geoffrey Blainey said in 2012 that he believed 26 January worked well as Australia Day and that it was at that time more successful than it had ever been.[77]

2010s

[edit]A January 2017 poll conducted by McNair yellowSquares for The Guardian found that 68% of Australians felt positive about Australia Day, 19% were indifferent and 7% had mixed feelings, with 6% feeling negative about Australia Day. Among Indigenous Australians, however, only 23% felt positive about Australia Day, 31% were negative and 30% had mixed feelings, with 54% favouring a change of date.[78] A September 2017 poll conducted by Essential Polling for The Guardian found that 54% were opposed to changing the date; 26% of Australians supported changing the date and 19% had no opinion.[79][80]

A poll conducted by progressive public policy think tank The Australia Institute in 2018 found that 56% do not mind what day it is held.[81] The same poll found that 49% believe that the date should not be on a date that is offensive to Indigenous Australians, but only 37% believed the current date was offensive.[82]

Prior to Australia Day 2019, the conservative public policy think tank Institute of Public Affairs (IPA) published the results of a poll in which 75% of Australians wanted the date to stay, while the new nationalist Advance Australia Party's poll had support at 71%. Both groups asked questions about pride in being Australian prior to the headline question.[80]

The Social Research Centre, a subsidiary of the Australian National University, also released a report in January 2019.[66] Their survey found that, when respondents know that 26 January is the anniversary of the arrival of the First Fleet at Port Jackson, 70% believe it is the best date for Australia Day, and 27% believe it is not. The report includes demographic factors which affect people's response, such as age, level of education, and state or territory of residence. Those who did not support 26 January as the best date then indicated their support for an alternative date. The three most supported dates were 27 May, 1 January and 8 May.[citation needed]

2020s

[edit]Polling by Essential Media since 2015 suggests that the number of people celebrating Australia Day is declining, indicating a shift in attitudes. In 2019, 40% celebrated the day; in 2020, 34%, and in 2021 it was down to 29% of over 1000 people surveyed. In 2021, 53% said that they were treating the day as just a public holiday.[83]

An IPA poll commissioned in December 2020 and published in January 2021 showed that support for changing the date had remained a minority position.[84][85][86][87] In January 2021, an Essential poll reported that 53% supported a separate day to recognise Indigenous Australians; however only 18% of these thought that it should replace Australia Day. A poll by Ipsos for The Age / The Sydney Morning Herald reported in January 2021 that 28% were in support of changing the date, 24% were neutral and 48% did not support changing the date. 49% believed that the date would change within the next decade and 41% believed that selecting a new date would improve the lives of Indigenous Australians. Results were split by demographic factors, with age being a significant factor. 47% of people aged 18–24 supported changing the date, compared to only 19% among those aged 55 years or older. Individuals who voted for the Greens were most likely to support the date change at 67%, followed by Labor voters at 31% and Coalition voters at 23%.[88]

A January 2022 IPA poll found 65% were opposed to changing the date, including 47% of 18–24 year olds, with 15% of the general population and 25% of 18–24 year olds in favour of changing it.[89] However an Essential poll around the same time reported growing support for a change of date or an additional day of celebration for Indigenous Australians, at nearly 60%.[90]

A January 2023 Roy Morgan poll found that 64% said that 26 January should be known as "Australia Day". A majority of respondents under 35 favoured "Invasion Day", as did a majority of Greens supporters. Support for the name "Australia Day" was up across every age group compared to the year prior, with support for the name up by eight percentage points among respondents aged 18–24. Majorities of men, women, capital city residents, country residents, Coalition and Labor supporters and respondents in each state favoured "Australia Day".[91]

References

[edit]- ^ "Australia Day". National Library of Australia. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "The many different dates we've celebrated Australia Day". SBS Voices. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Australia Day Indigenous reactions". www.aph.gov.au. 25 January 2018. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Seeing Australia Day through Indigenous eyes". CoAct. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Bongiorno, Frank (21 January 2018). "Why Australia Day survives, despite revealing a nation's rifts and wounds". The Conversation. Retrieved 23 January 2022.

- ^ Jones, Benjamin T. (25 January 2023). "Australia Day wasn't always January 26, but it was always an issue". The Conversation. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ "Public and Bank Holidays Amendment Act 1992 (WA)" (PDF). Government of Western Australia Department of Justice Parliamentary Counsel's Office. 17 June 1992. Retrieved 25 January 2024.

- ^ Aubrey, Sophie (22 January 2023). "Is the fate of Australia Day heading only in one direction?". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 29 January 2023.

- ^ a b c d e f Ballantine, Derek (5 December 1999). "Australia Day 'should be changed'". Sunday Tasmanian. Hobart. p. 6.

- ^ a b Nicholson, Rod (25 January 2009). "Ron Barassi wants an Australia Day we can all enjoy". Herald Sun. Melbourne. Archived from the original on 3 July 2009. Retrieved 29 December 2009.

- ^ Narushima, Yuko (23 January 2010). "Obey the law at least, Abbott tells migrants". The Sydney Morning Herald.

- ^ Wahlquist, Calla (19 January 2018). "What our leaders say about Australia Day – and where did it start, anyway?". Guardian Australia. Retrieved 5 June 2019.

- ^ a b Tippet, Gary (25 January 2009). "90 years apart and bonded by a nation". Melbourne: Australia Day Council of New South Wales. Archived from the original on 31 January 2009. Retrieved 25 January 2009.

- ^ Wellington, Shahni (23 January 2022). "Indigenous activism heads online as the Aboriginal Tent Embassy celebrates 50 years". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 22 November 2022.

- ^ "Reconciliation can start on Australia Day". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. 29 January 2007. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 18 December 2008.

- ^ "Invasion Day marked by thousands of protesters calling for equal rights, change of date". ABC News. 27 January 2018. Retrieved 30 January 2018.

- ^ "Australia Day 2018: Thousands turn out for protest in Melbourne CBD". Herald Sun. 26 January 2018. Retrieved 28 January 2018.

- ^ Knaus, Christopher; Wahlquist, Calla (26 January 2018). "'Abolish Australia Day': Invasion Day marches draw tens of thousands of protesters". The Guardian. Retrieved 27 January 2018.

- ^ "Invasion Day rally 2019: where to find marches and protests across Australia". The Guardian. 25 January 2019. Retrieved 25 January 2019.

- ^ Truu, Maani (26 January 2019). "Tens of thousands attend 'Invasion Day' rallies across Australia". SBS News. Archived from the original on 26 January 2019. Retrieved 26 January 2019.

- ^ a b Day, Mark (9 December 1999). "Time for a birthday with real meaning". Daily Telegraph. Sydney. p. 11.

- ^ Rodda, Rachel (27 January 2001). "Nation's birthday debate rekindled". Daily Telegraph. Sydney. p. 7.

- ^ "Rudd says 'no' to Australia Day date change". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 January 2009. Archived from the original on 13 December 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2009.

- ^ "Scott Morrison suggests new Indigenous national day instead of moving Australia Day". ABC News. 24 September 2018. Retrieved 5 March 2022.

- ^ "Liberal MP wants Australia Day to be protected by law which would mean a plebiscite to change the date". 10 play. 16 January 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Australia Day Bill 2023". Parliament of Australia. 2023. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

Introduced and read a first time 27 Mar 2023

- ^ "Local councils across country push for Australia Day date change". The Guardian. 21 June 2017. Retrieved 21 June 2017.

- ^ "Melbourne's Yarra council votes unanimously to move Australia Day citizenship ceremonies". Sydney Morning Herald. 16 August 2017. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Cowie, Tom (16 August 2017). "Yarra council stripped of citizenship power after cancelling Australia Day celebrations". The Age. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Wahlquist, Calla (16 August 2017). "Yarra council stripped of citizenship ceremony powers after Australia Day changes". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ Daley, Paul (16 August 2017). "Turnbull is wrong – Australia Day and its history aren't 'complex' for Indigenous people". The Guardian. Retrieved 16 August 2017.

- ^ "Darebin council stripped of citizenship ceremony after controversial Australia Day vote". ABC News. 22 August 2017. Retrieved 24 August 2017.

- ^ a b Zhou, Naaman (13 January 2019). "Scott Morrison to force councils to hold citizenship ceremonies on Australia Day". The Guardian. Retrieved 13 January 2019.

- ^ McNab, Heather (13 November 2019). "'The right thing to do': Sydney council drops Australia Day celebrations". Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 14 November 2019.

- ^ "'Mitcham Council backs mayor's push to join 'change the date of Australia Day' movement". The Advertiser. 3 March 2021. Retrieved 5 March 2021.

- ^ Segaert, Anthony (15 January 2024). "The Sydney council that's stepping in to offer Australia Day paraphernalia". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "Second big supermarket axes Australia Day merchandise". news.com.au. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ a b "Woolworths and Big W Australia Day decision prompts Peter Dutton to call for boycott". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 12 January 2024. Retrieved 12 January 2024.

- ^ "Two Woolworths stores defaced over Australia Day merchandise". news.com.au. 16 January 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "Second Brisbane Woolworths targeted with graffiti after supermarket announced it would stop selling Australia Day merchandise". 7news. 15 January 2024. Retrieved 16 January 2024.

- ^ "Brisbane Woolworths store vandalised with graffiti amid Australia Day merchandise controversy". Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 15 January 2024. Retrieved 15 January 2024.

- ^ "How Woolworths will serve our customers this Australia Day". Woolworths Group. Retrieved 25 July 2024.

- ^ "Dodson wants debate on Australia Day date change". ABC News. Australian Broadcasting Corporation. 26 January 2009. Archived from the original on 14 December 2009. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ Marlow, Karina (20 January 2016). "Australia Day, Invasion Day, Survival Day: What's in a name?". NITV. Retrieved 4 May 2023.

- ^ "Significant Aboriginal Events in Sydney". Sydney City Council website. Archived from the original on 4 February 2007. Retrieved 29 January 2007.

- ^ Frost, Natasha (27 January 2023). "Is Australia Day Approaching a Tipping Point?". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Vrajlal, Alicia (25 January 2023). "Changing The Date 'Doesn't Take Away The Pain' — So What Can Be Done About January 26?". www.refinery29.com. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Stonehouse, Greta (25 January 2023). "Protesters declare 'Australia Day is dead' as thousands attend rallies across the country". ABC News. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ Pearson, Luke (14 January 2019). "Why I no longer support #changethedate – IndigenousX". indigenousx.com.au. Retrieved 28 June 2023.

- ^ "*Ø* Wilson's Almanac free daily ezine". Wilson's Almanac. Archived from the original on 25 January 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ a b Hirst, John (26 January 2008). "Australia Day in question". The Age. Melbourne, Australia. Archived from the original on 13 January 2009. Retrieved 20 December 2008.

- ^ Macfarlane, Ian (26 January 2017). "Australia Day: let's shift it for a truly national celebration". The Australian. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- ^ "Home". Australia Day. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

- ^ Person, Noel (2021). Mission: Essays, Speeches and Ideas. Black. ISBN 9781743822050.

Linking 25 January and 26 January would be a noble compromise between the old and the new. It would bring together honour and empathy, remembrance and celebration

- ^ "Australia Day – let's make it a two-day festival". The New Daily. 26 January 2023. Retrieved 7 January 2024.

January 26 is the day when ancient Australia became modern Australia, but by including January 25 we would be recognising the ancient at the same time as our own history as new arrivals, and those who are still arriving.

- ^ "We only became independent of Britain on this day in 1986". The Australian. 3 March 2011.

- ^ Ballantyne, Derek (5 December 2009). "DUMP IT! – Australia Day boss says date divides the nation". The Sunday Mail. Brisbane. p. 1.

- ^ Stewart, Cameron (14 April 2001). "Anzac rethink enrages diggers". Weekend Australian. Sydney. p. 1.

- ^ "Anzac Day merger idea gets shot down". Hobart Mercury. Hobart. 26 April 2001. p. 1.

- ^ "Change the date: When should Australia Day be held?". News.com.au. 26 January 2017. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ Williams, Emma (12 January 2017). "Comedian has most Aussie solution for controversial Australia Day date". The Courier-Mail. Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ "May8 – The New Australia Day Mate!". Retrieved 25 January 2018.

- ^ a b "Day for all Australians". The Sydney Morning Herald. 26 January 2002.

- ^ Hudson, Fiona (10 May 2001). "Call to shift Australia Day". Hobart Mercury.

- ^ a b Turner, Jeff (26 January 2000). "Divided on our national day". The Advertiser. Adelaide. p. 19.

- ^ a b "Barbeques and black armbands | Social Research Centre". www.srcentre.com.au. Retrieved 5 January 2021.

- ^ Robin, Libby (2007). How a Continent Created a Nation. University of New South Wales Press. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-86840-891-0.

- ^ Searle, Suzette. "Australia Day – our day needs a new date" (PDF). wattleday.asn.au. Wattle Association Inc. Archived (PDF) from the original on 26 November 2021. Retrieved 26 November 2021.

- ^ Daley, Paul (19 June 2022). "Should the circumnavigation of Australia be marked as foundation day? Ted Egan thinks so | Paul Daley". Guardian Australia.

- ^ Admin (25 January 2020). "Here's a date that Governor Phillip and Bennelong might call Australia Day". ASGMWP. Retrieved 25 September 2023.

- ^ "Australian Citizenship Day, 17 September". Immigration and citizenship Website. Retrieved 29 September 2023.

- ^ Williams, Warwick (21 January 2015). "October 24 significant". The Canberra Times. Archived from the original on 20 August 2018.

- ^ Hirst, John (26 January 2008). "Australia Day in question". The Age. Melbourne. Retrieved 26 December 2009.

- ^ a b Macgregor, Duncan; Leigh, Andrew; Madden, David; Tynan, Peter (29 November 2004). "Time to reclaim this legend as our driving force". The Sydney Morning Herald. p. 15.

- ^ "Our day 'parochial'". Daily Telegraph. Sydney. 6 December 1999. p. 15.

- ^ "Newspoll" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 11 May 2011. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ "?". Herald Sun. Archived from the original on 30 December 2012. Retrieved 15 October 2010.

- ^ Gabrielle Chan (26 January 2017). "Most Indigenous Australians want date and name of Australia Day changed, poll finds". The Guardian. Retrieved 26 January 2017.

- ^ Murphy, Katherine (5 September 2017). "Most voters want Australia Day to stay on 26 January – Guardian Essential poll". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ a b Taylor, Josh (16 January 2019). "Should Australia #ChangeTheDate? Polls Vary Depending On What Is Asked". BuzzFeed. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Borys, Stephanie (18 January 2018). "Australia Day: Most Australians don't mind what date it's held, according to new poll". ABC. Retrieved 18 January 2018.

- ^ "Australia Day poll: While many believe date shouldn't offend, many ignore significance of Jan 26". NITV. 18 January 2018. Retrieved 27 January 2019.

- ^ Foster, Ally (20 January 2021). "Australia Day poll shows how attitudes to changing the date have shifted". NewsComAu. Nationwide News Pty Limited. Retrieved 21 January 2021.

- ^ "Ipsos Australia Day Poll Report". Ipsos. 24 January 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Poll – Mainstream Australians Continue To Support Australia Day On 26 January". Institute of Public Affairs. 17 January 2021. Retrieved 22 March 2021.

- ^ "Australia Day Poll" (PDF). January 2021.

This poll of 1,038 Australians was commissioned by the Institute of Public Affairs. Data for this poll was collected by marketing research firm Dynata between 11–13 December 2020.

- ^ Topsfield, Jewel (24 January 2021). "Not going to solve anything: Why some Australians don't want a date change". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 2 March 2021.

- ^ Topsfield, Jewel (24 January 2021). "Almost half oppose campaign to change Australia Day: poll". The Sydney Morning Herald. Retrieved 26 January 2021.

- ^ "New Poll: Majority Of Australians Support Australia Day On 26 January". IPA – The Voice For Freedom. 16 January 2022. Retrieved 26 January 2022.

- ^ "Guardian Essential poll reveals growing support for changing the date of Australia Day". The Guardian. 25 January 2022. Retrieved 28 February 2022.

- ^ "Nearly two-thirds of Australians (64%) say January 26 should be known as 'Australia Day', virtually unchanged on a year ago". Roy Morgan. 24 January 2023. Retrieved 29 January 2023.