Jansenism

You can help expand this article with text translated from the corresponding article in French. (November 2014) Click [show] for important translation instructions.

|

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Christian theology |

|---|

|

|

|

Jansenism was a 17th- and 18th-century theological movement within Roman Catholicism, primarily active in the Kingdom of France, which arose as an attempt to reconcile the theological concepts of free will and divine grace, in response to certain developments in the Roman Catholic Church, later developing political and philosophical aspects in opposition to royal absolutism.

The very definition of Jansenism proves problematic, since Jansenists have rarely assumed this appellation, instead considering themselves to be Roman Catholics. They do, however, possess some characteristic traits, such as the profession of the doctrine of divine grace associated with Augustine of Hippo, as not only necessary for good works and salvation, but also as negating and renewing human free will in order to effect salvation. The Jansenists were also distinguished by their moral rigorism and hostility towards the Jesuits and ultramontanism. From the end of the 17th century, this theological movement gained a political aspect, with the opponents of royal absolutism being largely identified with Jansenism.

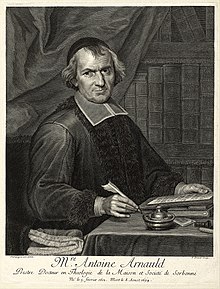

Jansenism began in the midst of the Counter-Reformation, and owes its name to the Dutch bishop of Ypres, Cornelius Jansen (1585-1638), the author of its foundational text, Augustinus, which was published posthumously in Leuven in 1640. The work was first popularised by Jansen's friend Abbot Jean du Vergier de Hauranne of Saint-Cyran-en-Brenne Abbey, and after Vergier's death in 1643, the movement was led by Antoine Arnauld. Augustinus was the culmination of controversies regarding grace dating back several decades, and coincided with the growing hostility of part of the Roman Catholic clergy towards the Jesuits. Jansen claimed to establish Augustine's true position on the subject, as opposed to the Jesuit view, which was said to give too great a role to free will in salvation.

Augustinus provoked lively debates, particularly in France, where five propositions, including the doctrines of limited atonement and irresistible grace, were extracted from the work and declared heretical by theologians hostile to Jansen.[1] These were condemned in 1653 by Pope Innocent X in the apostolic constitution Cum occasione. The defenders of Jansen responded by distinguishing between 'the law and the fact', arguing that the propositions were indeed heretical, but could not be found in Augustinus.

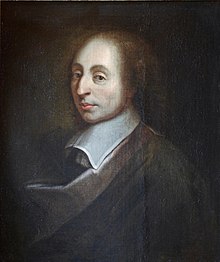

The Jansenists attacked Jesuit casuistry as laxity, in such works as the Lettres provinciales ('Provincial letters', fictional letters defending the Jansenist cause) by Blaise Pascal, which greatly affected French opinion on the matter. At the same time, the Port-Royal-des-Champs Abbey became a theological centre for the movement and a haven for writers including Vergier, Arnauld, Pascal, Pierre Nicole and Jean Racine, and Jansenism developed and gained popularity. In the late 17th century, Jansenists enjoyed a measure of peace under Pope Clement IX.

Nevertheless, Jansenism was opposed by many within the Roman Catholic hierarchy, especially the Jesuits. Although the Jansenists identified themselves only as rigorous followers of Augustine's teachings, Jesuits coined the term Jansenism to identify them as having Reformed leanings.[1] Jansenists were also considered enemies of the monarchy, and were very quickly targeted by royal power, with Louis XIV and his successors intensely persecuting them. The popes likewise demonstrated increasing severity towards them, notably with Clement XI abolishing the abbey of Port-Royal in 1708 and promulgating the bull Unigenitus in 1713, which further condemned Jansenist teachings.[2] This controversy did not end until Louis Antoine de Noailles, cardinal and archbishop of Paris, who had opposed the bull, signed it in 1728. In this context, Jansenism merged with the struggle against royal absolutism and ultramontanism during the 18th century. The clerics supporting the French Revolution and the Civil Constitution of the Clergy were thus largely Jansenists. However, Jansenism receded and disappeared in the 19th century, with the First Vatican Council declaring a definitive end to most of the debates which caused its initial appearance.

Definition[edit]

'A historical enigma' according to certain historians,[3] 'an adaptation to changing circumstances' according to others,[4] Jansenism had an evolution parallel to that of the Roman Catholic Church until the 19th century, without any uncontested unity to be found in it.

The term 'Jansenism' was rejected by those called 'Jansenists', who throughout history consistently proclaimed their unity with the Roman Catholic Church. Abbot Victor Carrière, precursor of contemporary studies of Jansenism, says the following.

There is perhaps no question more complicated than that of Jansenism. From the beginning, many of those who were rightly considered to be its legitimate representatives assert that it does not exist [...]. Moreover, in order to escape the condemnations of the Church, to disarm certain attacks and win new adherents, it has, depending on the circumstances, attenuated or even modified its fundamental theses. Thus, despite the countless works devoted to it, the history of Jansenism in its entirety still remains to be written today, since the spirit of polemic prevailed for two centuries.[5]

Jansenism is first of all a defence of Augustinian theology in a debate initiated by the Protestant Reformation and the Council of Trent,[6] then a concrete implementation of this Augustinianism. The struggle against ultramontanism and Papal authority gives it a Gallican character, which became an essential component of this movement. In the absolutist France of the 17th and 18th centuries, the fear of a transition from religious opposition to general opposition justified monarchical repression of Jansenism, and consequently, transformed the movement by giving it a political aspect marked by resistance to power and a defence of the parlements. In the 18th century, a diversity of 'Jansenisms' became more evident. In France, the participation of secular society in the movement revealed a miraculous and popular component involving figurism and the convulsionnaires. In northern Italy, the influence of the Austrian Enlightenment brought Jansenism closer to modernity. However in the 19th century, Jansenism was primarily a defence of the past and a struggle against modern developments in the Roman Catholic Church.

Augustin Gazier, historian of Jansenism and convinced Port-Royalist, attempts a minimal definition of the movement, removing the particularities to attribute a few common traits to all Jansenists: the subjection of one's whole life to a demanding form of Christianity, which gives a particular view of dogmatic theology, religious history and the Christian world. They harshly criticise developments in the church, but at the same time maintain an unshakeable loyalty to it.[7]

Taking a broader view, the estimation of Marie-José Michel is that the Jansenists occupy an empty space between the ultramontane project of Rome and the construction of Bourbon absolutism.

French Jansenism is a creation of Ancien Régime society [...]. Developed from an Augustinian background very firmly anchored in France, it unfolds in parallel with the two great projects of French absolutism and the Catholic reformation [the Counter-Reformation]. Its development by part of the French religious and secular elites gives it an immediate audience never reached by the other two systems. It is thus rooted in French mentalities, and it truly survives as long as its two enemies, that is to say until the French Revolution for one, and until the First Vatican Council for the other.[8]

We must not therefore therefore find in Jansenism a fixed theological doctrine defended by easily identifiable supporters claiming a system of thought, but rather the variable and diverse developments of part of French and European Roman Catholicism in the early modern period.

The heresy of 'Jansenism', as stated by subsequent Roman Catholic doctrine, lies in the denial of the role of free will in the acceptance and use of grace. Jansenism asserts that God's role in the infusion of grace cannot be resisted and does not require human assent. The Catechism of the Catholic Church states the Roman Catholic position that "God's free initiative demands man's free response"[9]—that is, humans freely assent or refuse God's gift of grace.

Origins[edit]

The question of grace in the post-Tridentine period[edit]

Jansenism originates from a theological school of thought within the framework of the Counter-Reformation, and appeared in the years following the Council of Trent, but draws from debates older than the council. Although Jansenism takes its name from Cornelius Jansen, it is attached to a long tradition of Augustinian thought.

Most of the debates contributing to Jansenism concern the relationship between divine grace (which God grants to man) and human freedom in the process of salvation. In the 5th century, the North African bishop Augustine of Hippo opposed the British monk Pelagius who maintained that man has, within himself, the strength to will the good and to practice virtue, and thus to carry out salvation; a position that reduces the importance of divine grace. Augustine rejected this and declared that God alone decides to whom he grants or withholds grace, which causes man to be saved. The good or evil actions of man (and thus, his will and his virtue) do not affect this process, since man's free will was lost as a result of the original sin of Adam. God acts upon man through efficacious grace, in such a way that he infallibly regenerates him, without destroying his will.[6] Man thus receives an irresistible and dominant desire for the good, which is infused into him by the action of efficacious grace.

Medieval theology, dominated by Augustinian thought, left little room for human freedom on the subject of grace. Thomas Aquinas, however, attempted to organise a system of thought around Augustinianism in order to reconcile grace and human freedom. He both affirmed the action of the divine in each action of man, and also the freedom of man.[6] The Scholastics of the 14th and 15th centuries moved away from Augustinianism towards a more optimistic view of human nature.[6]

The Reformation broke with Scholasticism,[6] with Martin Luther and John Calvin both taking Augustine as a reference but also representing radical views. For some Augustinians, it was only necessary to affirm the omnipotence of God against human freedom, as over-exalted in Pelagianism, whereas Luther and Calvin see grace (freely granted or withheld by God) as causing man to be saved. Man's free will is therefore totally denied.[10]

To counter the Reformation, the Roman Catholic Church in 1547 reaffirmed in the sixth session of the Council of Trent, the place of free will, without pronouncing on its relationship with grace.[6] Afterwards the Roman Catholic position was not entirely unified, with the Jesuit priest Diego Laynez defending a position that his detractors described as Pelagian.[6] In fact, the Jesuits restarted the debate, fearing that excessive Augustinianism would weaken the role of the Church in salvation and compromise the rejection of Protestantism.[6] In the wake of Renaissance humanism, certain Roman Catholics had a less pessimistic vision of man and sought to establish his place in the process of salvation by relying on Thomistic theology, which appeared to be a reasonable compromise between grace and free will.[6] It is in this context that Aquinas was proclaimed a Doctor of the Church in 1567.

Nevertheless, theological conflict increased from 1567, and in Leuven, the theologian Michel de Bay (Baius) was condemned by Pope Pius V for his denial of the reality of free will. In response to Baius, the Spanish Jesuit Luis de Molina, then teaching at the University of Évora, defended the existence of 'sufficient' grace, which provides man with the means of salvation, but only enters into him by the assent of his free will. This thesis was violently opposed by the Augustinians, which resulted in the Dicastery for the Doctrine of the Faith banning any publications on the problem of grace in 1611.[6]

The controversy was then concentrated in Leuven, where the Augustinian University of Leuven opposed the Jesuits.[6] In 1628, Cornelius Jansen, then a professor at the university, undertook the creation of a theological work aimed at resolving the problem of grace by synthesising Augustine's thought on the matter. This work, a manuscript of nearly 1,300 pages entitled Augustinus, was almost completed when Jansen died suddenly in an epidemic in 1638.[6] On his deathbed, he committed a manuscript to his chaplain, ordering him to consult with Libert Froidmont, a theology professor at Leuven, and Henricus Calenus, canon at the metropolitan church, and to publish the manuscript if they agreed it should be published, adding "If, however, the Holy See wishes any change, I am an obedient son, and I submit to that Church in which I have lived to my dying hour. This is my last wish."[11] Jansen affirmed in Augustinus that since the Fall of man, the human will is capable only of evil without divine help. Only efficacious grace can make him live according to the Spirit rather than the flesh, that is to say, according to the will of God rather than the will of man. This grace is irresistible and not granted to all men. Here Jansen agrees with Calvin's theory of predestination. The manuscript was published in 1640, expounding Augustine's system and forming the basis for the subsequent Jansenist controversy. The book consisted of three volumes:

- The first described the history of Pelagianism and Augustine's battle against it and against Semipelagianism;

- The second discussed the fall of man and original sin;

- The third denounced a "modern tendency" (unnamed by Jansen but clearly identifiable as Molinism) as Semipelagian.

In the first decade of the 17th century, Jansen established a fruitful collaboration with one of his classmates at the University of Leuven, the Baianist Jean du Vergier de Hauranne, later the abbot of Saint-Cyran-en-Brenne. Vergier was Jansen's patron for several years, getting Jansen a position as a tutor in Paris in 1606, after they completed their theological studies. Two years later, he got Jansen a position teaching at the bishop's college in Vergier's hometown of Bayonne. The two studied the Church Fathers together in Bayonne, with a special focus on the thought of Augustine, until both left Bayonne in 1617. The question of grace was not central to their works at that time.[6] Jansen returned to the University of Leuven, where he completed his doctorate in 1619 and was named professor of exegesis. Jansen and Vergier continued to correspond about Augustine, especially in regards to his teachings on grace. Upon the recommendation of King Philip IV of Spain, Jansen was consecrated as bishop of Ypres in 1636. It was only after the publication of Augustinus in 1638 that Vergier became the herald of the Augustinian theses, initially more out of loyalty to his late friend than out of personal conviction.

A form of French Augustinianism — Vergier and the Arnauds[edit]

Until then, grace was not frequently debated among French Roman Catholics, which was overshadowed by the devastating French Wars of Religion. The Jesuits were also banished from the kingdom between 1595 and 1603, so the Augustinian doctrine had no real opponents.

At the beginning of the 17th century, the principal religious movement was the French school of spirituality, mainly represented by the Oratory of Jesus founded in 1611 by Cardinal Pierre de Bérulle, a close friend of Vergier. The movement sought to put into practice a certain form of Augustinianism without focusing on the problem of grace as the Jansenists would later do. Its emphasis was to bring souls to a state of humility before God through the adoration of Christ as Saviour.[6] Although Bérulle interfered little in the debates on grace, the Oratory and the Jesuits still came into conflict, with Vergier taking part by publishing writings against the 'Molinists'.[6] Moreover, Bérulle, after having been the ally of Cardinal Richelieu, became his enemy when he realised Richelieu was not so much seeking the victory of Roman Catholicism in Europe, but rather seeking 'to construct a political synthesis which would ensure the universal supremacy of the French monarchy;'[6] placing himself in alignment with the royal jurists. When Bérulle died in 1629, Richelieu transferred his hostility towards Vergier,[6] mainly due to a theological debate regarding contrition, which had not been settled by the Council of Trent, that disinclined him to Vergier, making him, at least on this point, an ally of the Jesuits.

Vergier in his writings insisted on the necessity of a true 'inner conversion' (perfect contrition) for the salvation of a Christian; the only way, according to him, to be able to receive the sacraments of penance and the Eucharist. This process of inner conversion, called the praactice of 'renewals', is necessarily long and, once the state of conversion has been reached, the penitent must make the graces he has received bear fruit, preferably by leading a life of retreat.[6] This inner conversion is related to the doctrine of contrition in the remission of sins, that is, it was considered necessary to express love for God in order receive the sacraments. In opposition to Vergier, Richelieu in his book Instruction du chrétien ('Instruction of the Christian', 1619), along with the Jesuits, supported the thesis of attrition (imperfect contrition) that is, for them, the 'regret for sins based solely on the fear of hell' is sufficient for one to receive the sacraments.[6]

Around this time Vergier came into contact with the Arnaulds, a large family of the Parisian nobility. Putting into practice his Augustinian vision of salvation, he became the spiritual director of the abbey of Port-Royal-des-Champs and its abbess, Marie Angélique Arnauld.[6] In 1637, Antoine Le Maistre, nephew of Angélique Arnaud, retreated to Port-Royal fully immerse himself in the demanding spiritual practices he learned from Vergier.[6] He was thus the first of the Solitaires of Port-Royal, and his example would be followed by other pious men wishing to live in isolation. Vergier took particular care for the education of the youngest of the twenty children of the lawyer Antoine Arnauld, Antoine Arnauld le Grand, of whom he became the protector. A brilliant lawyer, Arnauld 'le Grand' became a priest and theologian at the Sorbonne in 1635. His talents as a lawyer would make him the spokesman for the Jansenists.

By allying with the Protestant princes against the Roman Catholic princes in the Thirty Years' War, Richelieu aroused the suspicion of the devout Jansenists, leading Vergier to openly condemn his foreign policy. For this reason he was imprisoned in the Bastille in May 1638.[6] The debate on the roles of contrition and attrition in salvation was also one of the motives of the imprisonment.[12] Vergier was not released until after Richelieu's death in 1642, and he died shortly thereafter, in 1643.

Having completed his thesis on Augustinianism, Arnauld, a brilliant orator, defended Augustinus and its author, Jansen. He would thus become the true herald and apologist for Jansenism in France. It was in Augustinus that emphasis was placed on the Augustinian theory of grace and predestination.[6]

Arnauld along with Pierre Nicole anonymously published the important textbook on logic Logique du Port-Royal ('Port-Royal Logic') in 1662.

The reception of Augustinus in France[edit]

Augustinus was first printed in France in 1641, then a second time in 1643. The debate regarding Augustinianism was introduced substantially into France by its publication.

The Oratorians and Dominicans welcomed the work, along with a large number of theologians at the Sorbonne. But the Jesuits immediately opposed it, who were supported by Cardinal Richelieu, and after his death in 1642, by Isaac Habert who attacked Jansen in his sermons at the Notre-Dame de Paris and by the Feuillant theologian Pierre de Saint-Joseph who published a Defensio sancti Augusti ('Defence of Saint Augustine') in 1643.

These first years were not favourable to the Augustinians; the archbishop of Paris, Jean-François de Gondi forbade the treatment of this subject in publications. The papal bull In eminenti, condemning the work as repeating previously condemned theses, was signed by Pope Urban VIII on the 6th of March, 1642, but thanks to the agitation of the Jansenists in the Parlement, its publication in France was delayed until January 1643.[13]

From 1640, the Jesuits condemned Jean du Vergier's practice of renewals, which, according to them, risked discouraging the faithful and therefore distancing them from the sacraments.[14] Antoine Arnauld responded to them in 1643 with De la fréquente communion ('Of frequent communion'),[15] in which he affirmed that this practice was only a return to the practices of the primitive Church. He also clearly explained the language of the practice. The work was approved by fifteen bishops and archbishops, as well as twenty-one theologians of the Sorbonne and was widely distributed except in Jesuit circles.[16]

In 1644, Antoine Arnauld published an Apologie pour Jansenius ('Apology for Jansenius') [17], then a Seconde apologie ('Second apology')[18] in the following year, and finally an Apologie pour M. de Saint-Cyran ('Apology for Saint-Cyran [Vergier]').[19]

Controversy and papal condemnation: 1640–1653[edit]

Augustinus was widely read in theological circles in France, Belgium, and the Netherlands in 1640, and a new edition quickly appeared in Paris under the approval of ten professors at the College of Sorbonne (the theological college of the University of Paris).

On August 1, 1642, however, the Holy Office issued a decree condemning Augustinus and forbidding its reading.[a] In 1642, Pope Urban VIII followed up with a papal bull entitled In eminenti, which condemned Augustinus because it was published in violation of the order that no works concerning grace should be published without the prior permission of the Holy See; and renewed the censures by Pope Pius V, in Ex omnibus afflictionibus in 1567, and Pope Gregory XIII, of several propositions of Baianism that were repeated in Augustinus.[b]

In 1602, Marie Angélique Arnauld became abbess of Port-Royal-des-Champs, a Cistercian convent in Magny-les-Hameaux. There, she reformed discipline after a conversion experience in 1608. In 1625, most of the nuns moved to Paris, forming the convent of Port-Royal de Paris, which from then on was commonly known simply as Port-Royal. In 1634, Vergier had become the spiritual adviser of Port-Royal-des-Champs and good friend of Angélique Arnauld; he convinced her of the rightness of Jansen's opinions. The two convents thus became major strongholds of Jansenism. Under Angélique Arnauld, later with Vergier's support, Port-Royal-des-Champs developed a series of elementary schools, known as the "Little Schools of Port-Royal" (Les Petites-Écoles de Port-Royal); the most famous product of these schools was the playwright Jean Racine.[22]

Through Angélique Arnauld, Vergier had met her brother, Antoine Arnauld, and brought him to accept Jansen's position in Augustinus. Following Vergier's death in 1643, Antoine Arnauld became the chief proponent of Jansenism. That same year he published De la fréquente Communion (On Frequent Communion), which presented Jansen's ideas in a way more accessible to the public (e.g., it was written in the vernacular, whereas Augustinus was written in Latin). The book focused on a related topic in the dispute between Jesuits and Jansenists. The Jesuits encouraged Roman Catholics, including those struggling with sin, to receive Holy Communion frequently, arguing that Christ instituted it as a means to holiness for sinners, and stating that the only requirement for receiving Communion (apart from baptism) was that the communicant is free of mortal sin at the time of reception. The Jansenists, in line with their deeply pessimistic theology, discouraged frequent Communion, arguing that a high degree of perfection, including purification from attachment to venial sin, was necessary before approaching the sacrament.

The faculty of the College of Sorbonne formally accepted the papal bull In eminenti in 1644, and Cardinal Jean François Paul de Gondi, archbishop of Paris, formally proscribed Augustinus; the work nevertheless continued to circulate.

The Jesuits then attacked the Jansenists, charging them with heresy similar to Calvinism.

Arnauld answered with Théologie morale des Jésuites ("Moral Theology of the Jesuits").[1]

The Jesuits then designated Nicolas Caussin (former confessor to Louis XIII) to write Réponse au libelle intitulé La Théologie morale des Jésuites ("Response to the libel titled Moral Theology of the Jesuits") in 1644. Another Jesuit response was Les Impostures et les ignorances du libelle intitulé: La Théologie Morale des Jésuites ("The impostures and ignorance of the libel titled Moral Theology of the Jesuits") by François Pinthereau, under the pseudonym of "abbé de Boisic", also in 1644.[23] Pinthereau also wrote a critical history of Jansenism, La Naissance du Jansénisme découverte à Monsieur le Chancelier ("The Birth of Jansenism Revealed to the Chancellor") in 1654.

During the 1640s, Vergier's nephew, Martin de Barcos, who was once a theology student under Jansen, wrote several works defending Vergier.

In 1649, Nicolas Cornet, syndic of the Sorbonne, frustrated by the continued circulation of Augustinus, drew up a list of five propositions from Augustinus and two propositions from De la fréquente Communion and asked the Sorbonne faculty to condemn the propositions. Before the faculty could do so, the Parliament of Paris intervened and forbade the faculty to consider the propositions. The faculty then submitted the propositions to the Assembly of the French clergy in 1650, which submitted the matter to Pope Innocent X. Eleven bishops opposed this and asked Innocent X to appoint a commission similar to the Congregatio de Auxiliis to resolve the situation. Innocent X agreed to the majority's request, but in an attempt to accommodate the view of the minority, appointed an advisory committee consisting of five cardinals and thirteen consultors to report on the situation. Over the next two years, this commission held 36 meetings including 10 presided by Innocent X.[11]

The supporters of Jansenism on the commission drew up a table with three heads: the first listed the Calvinist position (which were condemned as heretical), the second listed the Pelagian/Semipelagian position (as taught by the Molinists), and the third listed the correct Augustinian position (according to the Jansenists).

Jansenism's supporters suffered a decisive defeat when the apostolic constitution Cum occasione was promulgated by Innocent X in 1653, which condemned the following five propositions:

- That there are some commands of God that just persons cannot keep, no matter how hard they wish and strive, and they are not given the grace to enable them to keep these commands;

- That it is impossible for fallen persons to resist interior grace;

- That it is possible for human beings who lack free will to merit;

- That the Semipelagians were correct to teach that prevenient grace was necessary for all interior acts, including for faith, but were incorrect to teach that fallen humanity is free to accept or resist prevenient grace; and;

- That it is Semipelagian to say that Christ died for all.

Formulary controversy[edit]

Background: 1654–1664[edit]

Antoine Arnauld condemned the five propositions listed in Cum occasione. He contended that Augustinus did not argue in favor of the five propositions condemned as heretical in Cum occasione. Rather, he argued that Jansen intended his statements in Augustinus in the same sense that Augustine of Hippo had offered his opinions, and Arnauld argued that since Innocent X would certainly not have wished to condemn Augustine's opinions, Innocent X had not condemned Jansen's actual opinions.

Replying to Arnauld, in 1654, 38 French bishops condemned Arnauld's position to the pope. Opponents of Jansenism in the church refused absolution to Roger du Plessis, duc de Liancourt for his continued protection of the Jansenists. In response to this onslaught, Arnauld articulated a distinction as to how far the Church could bind the mind of a Catholic. He argued that there is a distinction between de jure and de facto: that a Catholic was obliged to accept the Church's opinion as to a matter of law (i.e., as to a matter of doctrine) but not as to a matter of fact. Arnauld argued that, while he agreed with the doctrine propounded in Cum occasione, he was not bound to accept the pope's determination of fact as to what doctrines were contained in Jansen's work.

In 1656, the theological faculty at the Sorbonne moved against Arnauld. This was the context in which Blaise Pascal wrote his famous Lettres provinciales in defense of Arnauld's position in the dispute at the Sorbonne, and denouncing the "relaxed morality" of Jesuitism (Unlike Arnauld, Pascal did not accede to Cum occasione but believed that the condemned doctrines were orthodox. Nevertheless, he emphasized Arnauld's distinction about matters of doctrine vs. matters of fact.) The Letters were also scathing in their critique of the casuistry of the Jesuits, echoing Arnauld's Théologie morale des Jésuites.

However, Pascal did not convince the Sorbonne's theological faculty, which voted 138–68 to degrade Arnauld together with 60 other theologians from the faculty. Later that year, the French Assembly of the Bishops voted to condemn Arnauld's distinction of the pope's ability to bind the mind of believers in matters of doctrine but not in matters of fact; they asked Pope Alexander VII to condemn Arnauld's proposition as heresy. Alexander VII responded, in the apostolic constitution Ad sanctam beati Petri sedem promulgated in 1656, that "We declare and define that the five propositions have been drawn from the book of Jansenius entitled Augustinus, and that they have been condemned in the sense of the same Jansenius and we once more condemn them as such."[11]

In 1657, relying on Ad sanctam beati Petri sedem, the French Assembly of the Clergy drew up a formula of faith condemning Jansenism and declared that subscription to the formula was obligatory. Many Jansenists remained firmly committed to Arnauld's proposition; they condemned the propositions in Cum occasione but disagreed that the propositions were contained in Augustinus. In retaliation, Gondi interdicted the convent of Port Royal from receiving the sacraments. In 1660, the elementary schools run by Port-Royal-des-Champs were closed by the bull, and in 1661, the monastery at Port-Royal-des-Champs was forbidden to accept new novices, which guaranteed the convent would eventually die out.

Formulary: 1664[edit]

Four bishops sided with Port-Royal,[c] arguing that the Assembly of the French clergy could not command French Catholics to subscribe to something that was not required by the pope. At the urging of several bishops, and at the personal insistence of King Louis XIV, Pope Alexander VII sent to France the apostolic constitution Regiminis Apostolici in 1664, which required, according to the Enchiridion symbolorum, "all ecclesiastical personnel and teachers" to subscribe to an included formulary, the Formula of Submission for the Jansenists.[24]: n. 2020

Formulary controversy: 1664–1669[edit]

The Formula of Submission for the Jansenists was the basis of the Formulary Controversy. Many Jansenists refused to sign it; while some did sign, they made it known that they were agreeing only to the doctrine (questions of law de jure), not the allegations asserted by the bull (questions of fact de facto). The latter category included the four Jansenist-leaning bishops, who communicated the bull to their flocks along with messages that maintained the distinction between doctrine and fact. This angered both Louis XIV and Alexander VII. Alexander VII commissioned nine French bishops to investigate the situation.

Alexander VII died in 1667 before the commission concluded its investigation and his successor, Pope Clement IX, initially appeared willing to continue the investigation of the nine Jansenist-leaning bishops. However, in France, Jansenists conducted a campaign arguing that allowing a papal commission of this sort would be ceding the traditional liberties of the Gallican Church, thus playing on traditional French opposition to ultramontanism. They convinced one member of the cabinet (Lyonne) and nineteen bishops of their position, these bishops argued, in a letter to Clement IX, that the infallibility of the Church applied only to matters of revelation, and not to matters of fact. They asserted that this was the position of Caesar Baronius and Robert Bellarmine. They also argued, in a letter to Louis XIV, that allowing the investigation to continue would result in political discord.

Under these circumstances, the papal nuncio to France recommended that Clement IX accommodate the Jansenists. Clement agreed, and appointed César d'Estrées, bishop of Laon, as a mediator in the matter.[d] D'Estrées convinced the four bishops, Arnauld, Choart de Buzenval, Caulet, and Pavillon, to sign the Formula of Submission for the Jansenists (though it seems they may have believed that signing the formulary did not mean assent to the matters of fact it contained). The pope, initially happy that the four bishops had signed, became angry when he was informed that they had done so with reservations. Clement IX ordered his nuncio to conduct a new investigation. Reporting back, the nuncio declared: "they have condemned and caused to be condemned the five propositions with all manner of sincerity, without any exception or restriction whatever, in every sense in which the Church has condemned them". However, he reported that the four bishops continued to be evasive as to whether they agreed with the pope as to the matter of fact. In response, Clement IX appointed a commission of twelve cardinals to further investigate the matter.[11] This commission determined that the four bishops had signed the formula in a less than entirely sincere manner, but recommended that the matter should be dropped to forestall further divisions in the Church. The pope agreed and thus issued four briefs, declaring the four bishops' agreement to the formula was acceptable, thus instituting the "Peace of Clement IX" (1669–1701).

Case of Conscience and aftermath: 1701–1709[edit]

Although the Peace of Clement IX was a lull in the public theological controversy, several clergies remained attracted to Jansenism. Three major groups were:

- The duped Jansenists, who continued to profess the five propositions condemned in Cum occasione;

- The fins Jansénistes, who accepted the doctrine of Cum occasione but who continued to deny the infallibility of the Church in matters of fact;

- The quasi-Jansenists, who formally accepted both Cum occasione and the infallibility of the Church in matters of fact, but who nevertheless remained attracted to aspects of Jansenism, notably its stern morality, commitment to virtue, and its opposition to ultramontanism, which was also a political issue in France in the decades surrounding the 1682 Declaration of the clergy of France.

The quasi-Jansenists served as protectors of the "duped Jansenists" and the fins Jansénistes.

The tensions generated by the continuing presence of these elements in the French church came to a head in the Case of Conscience of 1701. The case involved the question of whether or not absolution should be given to a cleric who refused to affirm the infallibility of the Church in matters of fact (even though he did not preach against it but merely maintained a "respectful silence"). A provincial conference, consisting of forty theology professors from the Sorbonne, headed by Noël Alexandre, declared that the cleric should receive absolution.

The publication of this "Case of Conscience" provoked outrage among the anti-Jansenist elements in the Catholic Church. The decision given by the scholars was condemned by several French bishops; by Cardinal Louis Antoine de Noailles, archbishop of Paris; by the theological faculties at Leuven, Douai, and eventually Paris; and, finally, in 1703, by Pope Clement XI. The scholars who had signed the Case of Conscience now backed away, and all of the signatories withdrew their signatures and the theologian who had championed the result of the Case of Conscience, Nicolas Petitpied, was expelled from the Sorbonne.

Louis XIV and his grandson, Philip V of Spain, now asked the pope to issue a papal bull condemning the practice of maintaining a respectful silence as to the issue of the infallibility of the Church in matters of the dogmatic fact.

The pope obliged, issuing the apostolic constitution Vineam Domini Sabaoth, dated July 16, 1705. At the subsequent Assembly of the French Clergy, all those present, except P.-Jean-Fr. de Percin de Montgaillard, bishop of Saint-Pons, voted to accept Vineam Domini Sabaoth and Louis XIV promulgated it as binding law in France.

Louis also sought the dissolution of Port-Royal-des-Champs, the stronghold of Jansenist thought, and this was achieved in 1708 when the pope issued a bull dissolving Port-Royal-des-Champs. The remaining nuns were forcibly removed in 1709 and dispersed among various other French convents and the buildings were razed in 1709. The convent of Port-Royal Abbey, Paris, remained in existence until it was closed in the general dechristianisation of France during the French Revolution.

Case of Quesnel[edit]

Pasquier Quesnel had been a member of the Oratory of Jesus in Paris from 1657 until 1681, when he was expelled for Jansenism. He sought the protection of Pierre du Cambout de Coislin, bishop of Orléans, who harbored Quesnel for four years, at which point Quesnel joined Antoine Arnauld in Brussels, Flanders. In 1692, Quesnel published Réflexions morales sur le Nouveau Testament, a devotional guide to the New Testament that laid out the Jansenist position in strong terms. Following Arnauld's death in 1694, Quesnel was widely regarded as the leader of the Jansenists. In 1703, Quesnel was imprisoned by Humbertus Guilielmus de Precipiano, archbishop of Mechelen, but escaped several months later and lived in Amsterdam for the remainder of his life.

Réflexions morales did not initially arouse controversy; in fact, it was approved for publication by Félix Vialart de Herse, bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne, and recommended by Noailles. Neither Vialart nor Noailles appeared to have realized that the book had strongly Jansenist overtones, and had thought that they were simply approving a pious manual of devotion.[citation needed] However, in the years that followed, several bishops became aware of the book's Jansenist tendencies and issued condemnations: Joseph-Ignace de Foresta, bishop of Apt, in 1703; Charles-Béningne Hervé, bishop of Gap, in 1704; and both François-Joseph de Grammont, bishop of Besançon, and Édouard Bargedé, bishop of Nevers, in 1707. When the Holy Office drew the Réflexions morales to the attention of Clement XI, he issued the papal brief Universi dominici (1708), proscribing the book for "savoring of the Jansenist heresy"; as a result, in 1710, Jean-François de l'Escure de Valderil, bishop of Luçon, and Étienne de Champflour, bishop of La Rochelle, forbade the reading of the book in their dioceses.[11]

However, Noailles, who was now the cardinal archbishop of Paris was embarrassed and reluctant to condemn a book he had previously recommended and thus hesitated. As a result, Louis XIV asked the pope to settle the matter.[citation needed] The result was the apostolic constitution Unigenitus Dei Filius, promulgated by Pope Clement XI on September 8, 1713. It was written with the contribution of Gregorio Selleri, a lector at the College of Saint Thomas, the future Pontifical University of Saint Thomas Aquinas, Angelicum,[25] and later Master of the Sacred Palace, fostered the condemnation of Jansenism by condemning 101 propositions from the Réflexions morales of Quesnel as heretical, and as identical with propositions already condemned in the writings of Jansen.

Those Jansenists who accepted Unigenitus Dei Filius became known as Acceptants.

After examining the 101 propositions condemned by Unigenitus Dei Filius, Noailles determined that as set out in Unigenitus Dei Filius and apart from their context in the Réflexions morales, some of the propositions condemned by Unigenitus Dei Filius were in fact orthodox. He, therefore, refused to accept the apostolic constitution and instead sought clarifications from the pope.

In the midst of this dispute, Louis XIV died in 1715, and the government of France was taken over by Philippe II, Duke of Orléans, regent for the five-year-old Louis XV of France. Unlike Louis XIV, who had stood solidly behind Unigenitus Dei Filius, Philippe II expressed ambivalence during the Régence period. With the change in political mood, three theological faculties that had previously voted to accept Unigenitus Dei Filius – Paris, Nantes, and Reims – voted to rescind their acceptance.

In 1717, four French bishops attempted to appeal Unigenitus Dei Filius to a general council; the bishops were joined by hundreds of French priests, monks, and nuns, and were supported by the parlements. In 1718, Clement XI responded vigorously to this challenge to his authority by issuing the bull Pastoralis officii by which he excommunicated everyone who had called for an appeal to a general council. Far from disarming the French clergy, many of whom were now advocating conciliarism, the clergy who had appealed Unigenitus Dei Filius to a general council, now appealed Pastoralis officii to a general council as well. In total, one cardinal, 18 bishops, and 3,000 clergy of France supported an appeal to a general council. However, the majority of clergy in France (four cardinals, 100 bishops, 100,000 clergymen) stood by the pope. The schism carried on for some time, and it was not until 1728 that Louis Antoine de Noailles submitted to the pope and signed Unigenitus Dei Filius.

Factionalism[edit]

Jansenism persisted in France for many years but split "into antagonistic factions" in the late 1720s.

One faction developed from the convulsionnaires of Saint-Médard, who were religious pilgrims who went into frenzied religious ecstasy at the grave of François de Pâris, a Jansenist deacon in the parish cemetery of Saint-Médard in Paris. The connection between the larger French Jansenist movement and the smaller, more radical convulsionnaire phenomenon is difficult to state with precision. Brian Strayer noted, in Suffering Saints, almost all convulsionnaires were Jansenists, but very few Jansenists embraced the convulsionnaire phenomenon.[26]: 236

"The format of their seances changed perceptibly after 1732," according to Strayer. "Instead of emphasizing prayer, singing, and healing miracles, believers now participated in 'spiritual marriages' (which occasionally bore earthly children), encouraged violent convulsions [...] and indulged in the secours (erotic and violent forms of torture), all of which reveals how neurotic the movement was becoming." The movement descended into brutal cruelties that "clearly had sexual overtones" in their practices of penance and mortification of the flesh. In 1735 the parlements regained jurisdiction over the convulsionary movement, which changed into an underground movement of clandestine sects. The next year "an alleged plot" by convulsionnaire revolutionaries to overthrow the parlements and assassinate Louis XV was thwarted. The "Augustinian convulsionnaires" were then absconded from Paris to avoid police surveillance. This "further split the Jansenist movement."[26]: 257–265

According to Strayer, by 1741 the leadership was "dead, exiled, or imprisoned," and the movement was divided into three groups. The police role increased and the parlements role decreased "in the social control of Jansenism" but cells continued engaging in seances, torture,[e] and apocalyptic and treasonous rhetoric. By 1755 there were fewer than 800 convulsionnaires in France. In 1762 the parlements criminalized some of their practices "as 'potentially dangerous' to human life."[26]: 266–269, 272 The last crucifixion was documented in 1788.[26]: 282

Jansenists continued to publish anti-Jesuit propaganda through their magazine Nouvelles ecclésiastiques and played a central role in plotting and promoting the expulsion of the Jesuits from France in 1762–64.[27]

In the Spanish Netherlands and the Dutch Republic[edit]

This section needs additional citations for verification. (September 2022) |

As noted by Jonathan Israel[28] Jansenism initially had strong support in the Spanish Netherlands, where Jansen himself had been active, supported by such major figures of the Church Hierarchy as Jacobus Boon, Archbishop of Mechelen and Antonie Triest, Bishop of Ghent. Though the Church in the Spanish Netherlands eventually took up persecution of Jansenism – with Jansenist clergy being replaced by their opponents and the monument to Jansen in the Cathedral of Ypres being symbolically demolished in 1656 – the Spanish authorities were less zealous in this persecution than the French ones.

Where Jansenism persisted longest as a major force among Catholics was in the Dutch Republic, where Jansenism was actively encouraged and supported by the Republic's authorities. Jansenist refugees from France and the Spanish Netherlands were made welcome, increasing the Jansenist influence among Dutch Catholics. Politically, the Dutch Jansenists were more inclined than other Catholics to reach accommodation with the Protestant authorities and sought to make themselves independent of Papal control. Moreover, theologically the Jansenist doctrines were considered to be closer to the dominant Dutch Calvinism. Indeed, Dutch Jansenism (sometimes called "Quesnelism" after Pasquier Quesnel, who emerged as a major proponent of Jansenism in the 1690s) was accused by its opponents of being "Crypto-Calvinism within the Church". The controversy between Jansenists and anti-Jansenists (the latter naturally led by the Jesuits) increasingly tore up the Dutch Catholic Church in the late 17th and early 18th century – with the authorities of the Dutch Republic actively involved on the one side and the Papacy and Kings of France, Spain, Portugal, and Poland – on the other. Moreover, some Dutch Catholics seeking greater independence from Papal control were identified as being "Jansenists", even if not necessarily adhering to the theological doctrines of Jansenism.

Things came to an open split in April 1723, with the adherents of what would come to be known as the Old Catholic Church breaking away and appointing one of their numbers, the Amsterdammer Cornelis Steenhoven, as Archbishop of Utrecht to rival the Archbishop recognized by the Pope. Throughout the 18th century, these two rival Catholic Churches were active in competition. The question of whether, and to what degree, this breakaway Church was Jansenist was highly controversial – the Jesuits having a clear polemical interest in emphasizing its identification as such.

In the 19th century, Jansenists were part of the abolition societies in France. The Janists had criticized Jesuit missions in the New World and advocated for liberation.

Legacy[edit]

Unigenitus Dei Filius marks the official end of toleration of Jansenism in the Church in France, though quasi-Jansenists would occasionally stir in the following decades. By the mid-18th century, Jansenism proper had totally lost its battle to be a viable theological position within Catholicism. However, certain ideas tinged with Jansenism remained in circulation for much longer; in particular, the Jansenist idea that Holy Communion should be received very infrequently, and that reception required much more than freedom from mortal sin, remained influential until finally condemned by Pope Pius X, who endorsed frequent communion, as long as the communicant was free of mortal sin, in the early 20th century.

In 1677, a pro-Baianism faction from the theological faculty at Louvain submitted 116 propositions of moral laxity for censure to Pope Innocent XI, who selected 65 propositions from the submission and "limited himself to condemning the deviations of moral doctrine."[24]: p. 466 On the other hand, Pascal's criticism of the Jesuits also led Innocent XI to condemn,[citation needed] through the Holy Office, those 65 propositions in 1679,[24]: nn. 2101–2167 [f] "without naming the probabilism prevalent in Jesuit circles."[29] Those 65 propositions were taken chiefly from the writings of the Jesuits Antonio Escobar y Mendoza and Francisco Suarez.[according to whom?] All 65 propositions were censured and prohibited "as at least scandalous and pernicious in practice."[24]: n. 2167

At the pseudo-Synod of Pistoia, a proposition of Jansenist inspiration, to radically reform the Latin liturgy of the Roman Catholic Church, was passed. This proposition along with the entire Synod of Pistoia was condemned by Pius VI's bull Auctorem Fidei several years later.[30]

Jansenism was a factor in the formation of the independent Old Catholic Church of the Netherlands from 1702 to 1723, and is said to continue to live on in some Ultrajectine traditions, but this proposition began with accusations from the Jesuits.[according to whom?]

In Quebec, Canada, in the 1960s, many people rejected the Church, and many of its institutions were secularized. This process was justified frequently by charges that the Church in Quebec was "Jansenist".[citation needed] For instance, Paul-Emile Borduas' 1948 manifesto Le Refus global accused the Church in Quebec as being the result of a "Jansenist colony".[failed verification – see discussion][31]

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The decree was powerless in France since the tribunal was unrecognized by the law.[20][21]

- ^ In eminenti was, for a time, treated as invalid because of an alleged ambiguity about the date of its publication. Jansenists attempted to prevent the reception of In eminenti, both in Flanders and in France. They pretended that it could not be genuine, since the document attested to be promulgated at Rome on March 6, 1641, whereas the copy sent to Brussels by the Nuncio at Cologne was dated in 1642. In reality, the difference between the Old Style and New Style dates was because two calendars were in use.[20]

- ^ Antoine and Angélique Arnauld's brother, Henri Arnauld, bishop of Angers; Nicolas Choart de Buzenval, bishop of Beauvais; François-Étienne Caulet, bishop of Pamiers; and Nicolas Pavillon, bishop of Alet.

- ^ Two bishops who had signed the letter to the pope, Louis Henri de Pardaillan de Gondrin, archbishop of Sens, and Félix Vialart de Herse, bishop of Châlons-sur-Marne, assisted d'Estrées.

- ^ For example, Strayer related a case documented in 1757 where a woman was "beat [...] with garden spades, iron chains, hammers, and brooms [...] jabbed [...] with swords, pelted [...] with stones, buried [...] alive, [...] crucified." In another case documented in 1757, a woman "was cut with a knife numerous times" causing gangrene.[26]: 269

- ^ The Holy Office decree that censured 65 propositions of moral doctrine is dated March 2, 1679.[24]: p. 466 The Holy Office previously censured 45 propositions of moral doctrine between two decrees dated September 24, 1665, and March 18, 1666.[24]: nn. 2021–2065 According to Denzinger, the propositions submitted, by both the University of Louvain and the University of Paris, were "frequently taken out of context and sometimes expanded by elements that are not found in the original, so that most often one must speak of fictitious authors."[24]: p. 459 The censure was that the 45 propositions were "at the very least scandalous."[24]: n. 2065

References[edit]

- ^ a b c Carraud, Vincent (21 January 2008) [20 June 2007]. "Le jansénisme" [Jansenism]. Bibliothèque électronique de Port-Royal (lecture) (in French). Société des Amis de Port-Royal. ISSN 1776-0755. Archived from the original on 11 November 2008.

- ^ Toon Quaghebeur, "The Reception of Unigenitus in the Faculty of Theology at Louvain, 1713-1719", Catholic Historical Review 93/2 (2007), pp. 265-299.

- ^ Chantin, Jean-Pierre (1996). Le Jansénisme. Entre hérésie imaginaire et résistance catholique [Jansenism. Between imaginary heresy and Catholic resistance.] (in French). Paris: Cerf. pp. introduction.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Taveneaux, René (1985). La Vie quotidienne des jansénistes aux XVIIe et XVIIIe siècles [The daily life of Jansenists in the 17th and 18th centuries] (in French). Hachette. pp. introduction.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Carrière, Abbé Victor (1936). Introduction aux études d'histoire ecclésiastique locale, tome 3 [Introduction to local ecclesiastical history studies, vol. 3] (in French). Paris. p. 513.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) CS1 maint: location missing publisher (link) - ^ a b c d e f g h i j k l m n o p q r s t u v w Cognet, Louis (1967). Le Jansénisme [Jansenism] (in French). PUF. p. 33. ISBN 978-2-13-038900-2.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Gazier, Augustin. Histoire générale du mouvement janséniste, tome 2, chapitre 29 [General history of the Jansenist movement, vol. 2, ch. 29] (in French).

- ^ Michel, Marie-José (2000). Jansénisme et Paris ; 1640 - 1730 [Jansenism and Paris: 1640-1730] (in French). Klincksieck. p. 453.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Catholic Church (2003). Catechism of the Catholic Church. Doubleday. n. 2002. ISBN 0-385-50819-0.

- ^ Chantin, Jean-Pierre (1996). Le Jansénisme. Entre hérésie imaginaire et résistance catholique [Jansenism. Between imaginary heresy and Catholic resistance.] (in French). Cerf. p. 10.

- ^ a b c d e

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Forget, Jacques (1910). "Jansenius and Jansenism". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

One or more of the preceding sentences incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Forget, Jacques (1910). "Jansenius and Jansenism". In Herbermann, Charles (ed.). Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 8. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ Pascal, Blaise (2004). Ferreyrolles, Gérard; Sellier, Philippe (eds.). Les provincials; Pensées; [et opuscules divers]. Paris: Livre de Poche. pp. 430–431. ISBN 2253132772.

- ^ Hildesheimer, Françoise (1992). Le Jansénisme [Jansenism] (in French). Desclée de Brouwer. p. 21.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Chantin, Jean-Pierre (1996). Le Jansénisme. Entre hérésie imaginaire et résistance catholique [Jansenism. Between imaginary heresy and Catholic resistance.] (in French). Cerf. p. 16.

- ^ Arnaud, Antoine (1643). De la fréquente Communion ou les sentimens des Pères, des papes et des Conciles, touchant l'usage des sacremens de pénitence et d'Eucharistie, sont fidèlement exposez, par M. A. Arnauld prestre Docteur [Of frequent communion or the views of the Fathers, popes and councils, touching the usage of the sacraments of penance and the Eucharist, faithfully exposited by Mr. A. Arnaud priest and theologian.] (in French). Paris: A. Vitré. p. 790.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Hildesheimer, Françoise (1992). Le Jansénisme [Jansenism] (in French). Desclée de Brouwer. p. 21.

- ^ Arnaud, Antoine (1644). Apologie de Monsieur Jansenius evesque d'Ipre & de la doctrine de S. Augustin, expliquée dans son livre, intitulé, Augustinus. Contre trois sermons de Monsieur Habert, theologal de Paris, prononcez dans Nostre-Dame, le premier & le dernier dimanche de l'advent 1642. & le dimanche de la septuagesime 1643 [Apology of Mr. Jansenius, bishop of Ypres & the doctrine of St. Augustine, explained in his book titled 'Augustinus'. Against three sermons of Mr. Habert, theologian of Paris, pronounced in Notre-Dame, the first and the last Sunday of Advent 1642 and the Sunday of the Septuagesima 1643.] (in French). s.l.s.n.

- ^ Arnauld, Antoine (1645). Seconde Apologie pour Monsieur Jansenius, évesque d'Ipre, & pour la doctrine de S. Augustin expliquée dans son livre intitulé « Augustinus » : contre la Response que Monsieur Habert, théologal de Paris, a faite à la première Apologie, & qu'il a intitulée « La Défense de la foy de l'Eglise, &c » [Second apology for Mr. Jansenius, bishop of Ypres, & for the doctrine of St. Augustine explained in his book titled 'Augustinus': against the response that Mr. Habert, theologian of Paris, made to the first apology, & which was entitled 'The Defence of the faith and the Church, etc.'] (in French). s.l.s.n.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ Arnauld, Antoine (1644). Apologie pour feu M. l'Abbé de Saint-Cyran, contre l'extrait d'une information prétendue que l'on fit courir contre luy l'an 1638, et que les Jésuites ont fait imprimer depuis quelques mois, à la teste d'un libelle intitulé : Sommaire de la théologie de l'abbé de Saint-Cyran et du sieur Arnauld [Apology for the late Abbey of Saint-Cyran, against the extract of certain alleged material that was circulated against him in the year 1638, and which the Jesuits printed several months ago, at the head of a libelle entitled: 'Summary of the theology of the abbey of Saint-Cyran and of Sir Arnauld'.] (in French) (1st ed.). s.l.s.n.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: date and year (link) - ^ a b Jervis, Lady Marian (1872). Tales of the boyhood of great painters. T. Nelson and Sons. pp. 386–387. Retrieved 23 March 2022.

- ^ Jervis 1872, p. 386–387.

- ^ "Jansenism: a movement of great influence". Musée protestant.

- ^ Abbé de Boisic (pseud. of Pinthereau, François) (1644). Les impostures et les ignorances du libelle, intitulé: la théologie morale des Jésuites (in French). [s.l.]: [s.n.] OCLC 493191187.

- ^ a b c d e f g h Denzinger, Heinrich; Hünermann, Peter; et al., eds. (2012). "Compendium of Creeds, Definitions, and Declarations on Matters of Faith and Morals". Enchiridion symbolorum: a compendium of creeds, definitions and declarations of the Catholic Church (43rd ed.). San Francisco: Ignatius Press. ISBN 978-0898707465.

- ^ Miranda, Salvador (ed.). "Selleri, O.P., Gregorio". The Cardinals of the Holy Roman Church. Florida International University Libraries. Archived from the original on 2 May 2005. Retrieved 5 February 2012.

- ^ a b c d e Strayer, Brian E. (2008). Suffering Saints: Jansenists and Convulsionnaires in France, 1640–1799. Brighton, UK: Sussex Academic Press. ISBN 9781845195168.

- ^ Dale Van Kley, The Jansenists and the Expulsion of the Jesuits from France 1757–1765

- ^ Jonathan Israel, "The Dutch Republic, Its Rise, Greatness and Fall", Clarendon Press, Oxford, 1995, pp. 649-653, 1034-1047)

- ^ Kelly, John N. D.; Walsh, Michael J. (2010). "Innocent XI, Bl". A dictionary of popes. Oxford paperback reference (2nd ed.). Oxford [u.a.]: Oxford University Press. pp. 290–291. ISBN 9780199295814.

- ^ Herbermann, Charles, ed. (1911). . Catholic Encyclopedia. Vol. 12. New York: Robert Appleton Company.

- ^ "Refus Global by Paul-Émile Borduas". Archived from the original on 25 March 2015. Retrieved 13 June 2015.

Further reading[edit]

- Abercrombie, Nigel (1936). The Origins of Jansenism. Oxford Studies in Modern Languages and Literature. Oxford: Clarendon Press. OCLC 599986225.

- Hamscher, Albert N. (1977). "The Parlement of Paris and the Social Interpretation of Early French Jansenism". Catholic Historical Review. 63 (3). Catholic University of America Press: 392–410. ISSN 0008-8080. JSTOR 25020157.

- Doyle, William (1999). Jansenism--Catholic Resistance to Authority from the Reformation to the French Revolution. Studies in European History. New York: St. Martin's Press. ISBN 9780312226763.

- Hudson, David (1984). "The 'Nouvelles Ecclésiastiques', Jansenism, and Conciliarism, 1717-1735". Catholic Historical Review. 70 (3). Catholic University of America Press: 389–406. ISSN 0008-8080. JSTOR 25021866.

- Ogg, David. Europe in the 17th Century (8th ed. 1960): 323-364.

- Schmaltz, Tad M. (January 1999). "What has Cartesianism to do with Jansenism?". Journal of the History of Ideas. 60 (1). University of Pennsylvania Press: 37–56. doi:10.1353/jhi.1999.0009. ISSN 0022-5037. JSTOR 3653999. S2CID 170706121.

- Van Kley, Dale (Fall 2006). "The Rejuvenation and Rejection of Jansenism in History and Historiography: Recent Literature on Eighteenth-century Jansenism in French". French Historical Studies. 29 (4). Duke University Press: 649–684. doi:10.1215/00161071-2006-016. ISSN 0016-1071.

- Strayer, E. Brain, Suffering Saints: Jensenits and Convulsionaries in France, 1640–1799 (Eastborne, Sussex Academic Press, 2008)

- Crichton. D. J., Saints or Sinners?: Jansenism and Jansenisers in Seventeenth Century France (Dublin, Veritas Publications, 1996)

- Swann Julian, Politics and the Parliament of Paris under Louis XV 1754–1774 (Cambridge, Cambridge University Press, 1995)

- Doyle William, Jansenism: Catholic Resistance to Authority from the Reformation to the French Revolution: Studies in European History (Basingstoke, Macmillan Press Ltd, 2000)