Competitive eating

Competitive eating, or speed eating, is a sport in which participants compete against each other to eat large quantities of food, usually in a short time period. Contests are typically eight to ten minutes long, although some competitions can last up to thirty minutes, with the person consuming the most food being declared the winner. Competitive eating is most popular in the United States, Canada, and Japan, where organized professional eating contests often offer prizes, including cash.

History

[edit]Precursors

[edit]

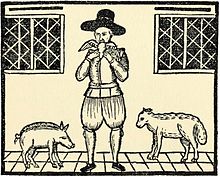

An early competitive eater was Nicholas Wood, the Great Eater of Kent, whose skill was featured in Iohn Taylor's 1630 pamphlet The great eater, of Kent, or Part of the admirable teeth and stomacks exploits of Nicholas Wood.[1] The pamphlet, which Taylor asserts is factually true, reports a series of Wood's stunts including eating a whole sheep raw in one sitting (excluding the wool, horns, and bones), 7 dozen rabbits in one meal, and nearly 400 pigeons in another meal.[2] He was a local celebrity in Kent and performed at fairs, festivals, and accepting eating challenges from wealthy patrons. He lost a wager on two occasions: once for being unable to finish ale-soaked bread, and another time at the home of Sir William Sedley, when he overate and fell into an 8-hour food coma; after he awakened, Sedley's servants put Wood in the stocks to shame him for his failure.[3]

19th century

[edit]

The first recorded pie eating contest took place in Toronto in 1878. It was organized as a charity fundraising event and won by Albert Piddington. It is not known how many pies were consumed. The prize was a "Handsomely Bound Book".[4] Following this, eating contests – particularly those involving pie – became popular across Canada and the United States, traditionally at county fairs.

There are some notable examples of early eating contestants, such as Joe McCarthy, who consumed 31 pies in a competition held at Charles Tanby's Saloon in 1897.[4] Frank Dotzler is also noteworthy after consuming "275 oysters, 8 & 1/8th pounds of steak, 12 rolls, and 3 large pies, all washed down with 11 cups of coffee" at an event organised by the Manhattan Fat Men's Club in 1909.[5]

Modern times

[edit]The recent surge in the popularity of competitive eating is due in large part to the development of the Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest, an annual holiday tradition that has been held on July 4 every year since 1916 at Coney Island. While the origins are debated, it is believed to have begun as a result of four immigrants who tried to eat as many hot dogs as possible to show off their patriotism.[6] In 2010, however, promoter Mortimer Matz admitted to having fabricated the legend of the 1916 start date with a man named Max Rosey in the early 1970s as part of a publicity stunt.[7] The legend grew over the years, to the point where The New York Times and other publications were known to have repeatedly listed 1916 as the inaugural year, although no evidence of the contest exists.[7] As Coney Island is often linked with recreational activities of the summer season, several early contests were held on other holidays associated with summer besides Independence Day; Memorial Day contests were scheduled for 1972,[8] 1975,[9] and 1978,[10] and a second 1972 event was held on Labor Day.[11]

The organisation of Major League Eating (MLE) in 1997 was also a key development in the increasing popularity.[12] The organisation is responsible for between 70 and 80 eating contests per year across North America, most notably Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest, which has aired on ESPN since 2003.[13]

As of 2023, the most successful male competitor is Joey Chestnut, who has won Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest a total of sixteen times since 2007. Chestnut also holds the record for most hot dogs consumed in the contest, with 76 in 2021.[14] The second most successful is Takeru Kobayashi, who won six consecutive titles from 2001 to 2006.[15] Both men hold multiple world records relating to eating, with Kobayashi holding 5,[16] and Chestnut 14.[17] Bob Shoudt "Notorious B.O.B." won the largest prize ever in a professional eating contest in the 2017 Philadelphia Wing Bowl - $50,000 in prizes (Hyundai Santa Fe, $10,000, ring and medallion).[18]

In 2011, Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest introduced a female-only tournament. The most successful competitor in this contest is Miki Sudo, with nine wins since 2014.[19] She is the reigning female champion as of 2023 and also holds the record for most hot dogs eaten by a female contestant, with 48.5.[20] She currently holds 3 world records.[21]

Contest structure

[edit]Food

[edit]The type of food used in contests varies greatly, with each contest typically only using one type of food (e.g. a hot dog eating contest). Foods used in professional eating contests include hamburgers, hot dogs,[22] pies, pancakes, chicken wings, asparagus, stinging nettles, pizza, ribs, whole turkeys, among many other types of food. Foods can reflect local cultures, such as vegan hot dogs in Austin, Texas.[23]

Rules and overview of events

[edit]Competitive eating contests often adhere to an 8, 10, 12, or 15 minute time limit. Most contests are presided over by a master of ceremonies, whose job is to announce the competitors prior to the contest and keep the audience engaged throughout the contest with enthusiastic play-by-play commentary and amusing anecdotes. A countdown from 10 usually takes place at the end of the contest, with all eating coming to an end with the expiration of time.

Many professional contests also employ a series of judges, whose role is to enforce the contest rules and warn eaters about infractions. Judges will also be called upon to count or weigh each competitor's food and certify the results of the contest prior to the winner being announced.

Many eaters will attempt to put as much food in their mouths as possible during the final seconds of a contest, a practice known by professionals as "chipmunking".[24] If chipmunking is allowed in a contest, eaters are given a reasonable amount of time (typically less than two minutes) to swallow the food or risk a deduction from their final totals.

In many contests, eaters are allowed to dunk foods in water or other liquids in order to soften the food and make it easier to chew and swallow. Dunking typically takes place with foods involving a bun or other doughy parts. Professional contests often enforce a limit on the number of times competitors are allowed to dunk food.

Competitors are required to maintain a relatively clean eating surface throughout the contest. Excess debris after the contest results in a deduction from the eater's final totals.

If, at any point during or immediately after the contest, a competitor regurgitates any food, he or she will be disqualified. Vomiting, also known as a "reversal", or, as ESPN and the Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest call it, a "reversal of fortune", includes obvious signs of vomiting as well as any small amounts of food that may fall from the mouth deemed by judges to have come from the stomach. Small amounts of food already in the mouth prior to swallowing are excluded from this rule.

Training and preparation

[edit]Many professional competitive eaters undergo rigorous personal training in order to increase their stomach capacity and eating speed with various foods. Stomach elasticity is usually considered the key to eating success, and competitors commonly train by drinking large amounts of water over a short time to stretch out the stomach. Others combine the consumption of water with large quantities of low calorie foods such as vegetables or salads. Some eaters chew large amounts of gum in order to build jaw strength.[25] Perhaps paradoxically, maintaining a low body fat percentage is thought to be helpful in competitive eating; this is known as the belt of fat theory. One competitive eater told the New York Times that he credits his 100-pound weight loss to his training regimen, which includes gym workouts and being "health-conscious the other six days out of the week".[26]

For a marquee event like the Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest, some eaters, like current contest champion Joey Chestnut, will begin training several months before the event with personal time trials using the contest food.[27] Retired competitive eater Ed "Cookie" Jarvis trained by consuming entire heads of boiled cabbage followed by drinking up to two gallons of water every day for two weeks before a contest.[28] Due to the risks involved with training alone or without emergency medical supervision, the IFOCE actively discourages training of any sort.[29]

Organizations

[edit]All Pro Eating

[edit]All Pro Eating Competitive Eaters include Molly Schuyler, Eric "Silo" Dahl, Jamie "The Bear" McDonald and Stephanie "Xanadu" Torres (deceased).[30][31]

IFOCE

[edit]The International Federation of Competitive Eating (IFOCE) hosts nearly 50 "Major League Eating" events[32] across North America every year.

Other challenges

[edit]Eating contests sponsored by restaurants can involve a challenge to eat large or extraordinarily spicy food items, including giant steaks, hamburgers and curries in a set amount of time. Those who finish the item are often rewarded by getting the item for free, a T-shirt, and/or their addition to a wall of challenge victors. For example, Ward's House of Prime located in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, has a prime rib meat challenge. The current record is 360 ounces by Molly Schuyler in June 2017.[citation needed]

Various challenges of this type are featured in the Travel Channel reality show Man v. Food, which premiered in 2008.[citation needed]

This type of challenge was satirized in 1998 King of the Hill episode "And They Call It Bobby Love". The A.V. Club claimed that Bobby completing the steak eating contest to spite his vegetarian ex-girlfriend "remains one of the best scenes in the show's history."[33]

Televised contests

[edit]- The annual Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest, which has been held every Fourth of July since the 1970s,[34] is televised live on ESPN from Coney Island in the Brooklyn borough of New York City.

- The annual Krystal Square Off hamburger eating contest has been televised on ESPN.

- In 2002, the Fox Network aired a two-hour competitive eating contest called the Glutton Bowl.

- Spike TV (now the Paramount Network) broadcast several IFOCE-sanctioned competitive eating competitions as part of its "MLE Chowdown" series.

Criticism and dangers

[edit]One criticism of competitive eating is the message that the gluttonous sport sends as obesity levels rise among Americans,[35] and the example it sets for youth.[36] In China, eating contests have been criticized for their promotion of food waste and "celebration of gluttony" in a time of rising of childhood obesity;[37] China passed a law in 2021 which banned competitive eating competitions and "mukbang" binge-eating videos in an effort to combat food waste, with offenders facing fines of up to 100,000 Yuan.[38][39]

Psychiatrist and eating disorder specialist Kim Dennis has stated that "somebody eating 70 hot dogs in 10 minutes is self-abuse to some extent" and warned that competitive eating carries "risks with regards to development of an eating disorder for people who had any sort of genetic predisposition to have one".[40] Competitive eater Patrick Bertoletti has compared competitive eating itself to an eating disorder, stating "It's like controlled bulimia. It's bulimia where you get paid for it. It's me trading on an eating disorder for money."[41]

Dangers

[edit]Negative health effects of competitive eating include delayed stomach emptying, aspiration pneumonia, perforation of the stomach, Boerhaave syndrome, and obesity.[42]

Other medical professionals contend that binge eating can cause stomach perforations in those with ulcers and gulping large quantities of water during training can lead to water intoxication, a condition caused by diluted electrolytes in the blood.[22] Long term effects of delayed stomach emptying include chronic indigestion, nausea and vomiting.[22]

Discomfort following an event is common with nausea, heartburn, abdominal cramping, and diarrhea.[43] People may also use laxatives or force themselves to vomit following the event, with associated risks.[43] Retired competitive eater Don "Moses" Lerman said that he would "stretch [his] stomach until it causes internal bleeding" in competitions.[44]

Deaths

[edit]Most deaths in competitive eating competitions have occurred from choking.[43]

- In October 2012, a 32-year-old man choked to death while competitively eating live roaches and worms.[45]

- In July 2013, a 64-year-old Australian man, Bruce Holland, died after choking during a pie eating contest.[46][47][48]

- On July 4, 2014, a 47-year-old competitive eater choked to death during a hot dog eating contest.[49]

- On March 11, 2016, a 45-year-old Indonesian man choked to death in a KFC speed-eating competition organized by an outside firm.[50][51]

- At a Sacred Heart University event on April 2, 2017, a 20-year-old female student choked to death during a pancake eating contest.[52][53]

- On August 13, 2019, a 41-year-old man choked to death after competing in an amateur taco eating competition at a Fresno Grizzlies baseball game.[54][55]

- On January 26, 2020, a woman died in Hervey Bay, Queensland after choking in a lamington-eating contest on Australia Day.[56][57][58][59]

- On October 17, 2021, Madie Nicpon, a 20-year-old Tufts University student, died after choking and falling unconscious during a hot dog eating contest.[60][61][62][63]

- On February 25, 2023, a 38-year-old woman died after choking in a pancake-eating contest on Maslenitsa.[64]

- On October 7, 2023, Natalie Buss, 37, from the village of Beddau in Wales, choked to death after taking part in a charity competition which involved fitting as many marshmallows in her mouth as possible.[65]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Taylor, Iohn (1630). The great eater, of Kent, or Part of the admirable teeth and stomacks exploits of Nicholas Wood, of Harrisom in the county of Kent His excessiue manner of eating without manners, in strange and true manner described, by Iohn Taylor.

{{cite book}}:|work=ignored (help) - ^ Felton, Bruce (2003). What Were They Thinking?: Really Bad Ideas Throughout History. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-1-59921-696-6.

- ^ Grundhauser, Eric (2017-07-11). "Competitive Eating Was Even More Gluttonous and Disgusting in the 17th Century". Atlas Obscura. Retrieved 2022-12-30.

- ^ a b "Roundtable | Pie Fight". Lapham's Quarterly. 22 November 2016. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Johnson, Adrienne Rose (August 1, 2016). "The Art of Competitive Eating". Gastronomica. 16 (3): 111–114. doi:10.1525/gfc.2016.16.3.111. ISSN 1529-3262.

- ^ Suddath, Claire (July 3, 2008). "A Brief History Of Competitive Eating". Time. ISSN 0040-781X. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ a b "No, He Did Not Invent the Publicity Stunt" by Sam Roberts, New York Times, August 18, 2010". The New York Times. August 18, 2010.

- ^ Robert D. McFadden (May 28, 1972). "Yesterday Was for Traveling, Strolling, Eating and Relaxing". New York Times.

- ^ Howard Thompson (May 26, 1975). "Going Out Guide". New York Times (p. 6).

- ^ "Two share prize". Ellensburg (Wash.) Daily Record (p. 11). May 31, 1978.

- ^ "105-Pound Girl Eats 12 Hot Dogs to Win Contest". St. Joseph (Mo.) News-Press (sec. A, p. 2). September 3, 1972.

- ^ "About us". majorleagueeating.com. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "The Rise of Major League Eating, America's New Favorite Pastime". Grandstand Central. July 25, 2019. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Joey Chestnut Sets New Record With 13th Hot Dog Eating Contest Win". NPR.org. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ Belson, Ken (July 5, 2007). "The Winner and New Champion, With 66 Hot Dogs (Published 2007)". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "World Record Holders and Breakers - Takeru Kobayashi". www.recordholdersrepublic.co.uk. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "World Record Holders and Breakers - Joey Chestnut". www.recordholdersrepublic.co.uk. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Notorious B.O.B. Wins Wing Bowl 25, Wingette of the Year is a shocker".

- ^ Desk, Sport (4 July 2020). "Miki Sudo sets women's record, wins seventh Nathan's Hot Dog Eating Contest | ESPN". The Global Herald. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

{{cite web}}:|last=has generic name (help) - ^ "Hot Dog Eating Contest Hall of Fame | Nathan's Famous". nathansfamous.com. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ "Miki Sudo's RecordSetter World Record Profile". recordsetter.com. Retrieved November 26, 2020.

- ^ a b c "Competitive Eating: How Safe Is It?". Webmd.com. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ "Scenes from a Vegan hot dog eating contest". 15 November 2013. Retrieved November 17, 2013.

- ^ Force Fed Archived 2007-05-22 at the Wayback Machine Creative Loafing blog May 9, 2007. Retrieved on June 30, 2009.

- ^ Eating champs to chow down at Everett wingding by Brian Alexander

- ^ Jinich, Pati (2024-07-01). "The Century-Long Saga of the Caesar Salad". The New York Times. Retrieved 2024-12-01.

- ^ Dworkin, Andy. "Champion competitive eater shares his training, victory" The Oregonian online. July 15, 2008. Retrieved on June 28, 2009.

- ^ Gullapalli, Diya. "You Have to Be in Good Shape To Eat 4.21 Hot Dogs a Minute" The Wall Street Journal. August 15, 2002. Retrieved on June 28, 2007.

- ^ "Major League Eating & International Federation of Competitive Eating". Ifoce.com. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ "All Pro Eating Promotions". Archived from the original on December 3, 2019. Retrieved February 6, 2017.

- ^ "'A little powerhouse:' Eaters remember Torres". Las Cruces Sun-News. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ "Major League Eating & International Federation of Competitive Eating". Ifoce.com. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ Koski, Genevieve (July 3, 2013). "10 Episodes That Made King of the Hill One of the Most Human Cartoons Ever". The A.V. Club. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved September 6, 2020.

- ^ Roberts, Sam (August 18, 2010). "Mortimer Matz, Press Agent Extraordinaire". The New York Times.

- ^ "Some find competitive eating hard to swallow." NBC News. November 21, 2007. Retrieved on July 4, 2009

- ^ Vasel, Kathryn. "Competitive Eating Contests Bring in the Dough Archived 2010-01-25 at the Wayback Machine." FoxBusiness.com. January 31, 2008. Retrieved on July 4, 2009.

- ^ "China's single children rapidly becoming overweight". www.telegraph.co.uk. 22 June 2011. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ "New food-waste law hard to stomach for China's binge-eating internet stars". South China Morning Post. 2020-12-31. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ Sheldon, Marissa (2021-05-11). "China Passes Law to Prevent Food Waste, Increase Food Security". NYC Food Policy Center (Hunter College). Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ Peter, Josh. "Inside the disturbing dangers of competitive eating". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ "Competitive Eater Patrick Bertoletti on hot dogs, vomit, and cold hard cash". The A.V. Club. 8 July 2014. Retrieved 2022-03-01.

- ^ Lim, TZ; Rajaguru, K; Lee, CL (June 2018). "The Perils of Competitive Speed Eating!". Gastroenterology. 154 (8): 2030–2032. doi:10.1053/j.gastro.2017.08.060. PMID 28870531.

- ^ a b c Albala, Ken (2015). The SAGE Encyclopedia of Food Issues. SAGE Publications. p. 275. ISBN 9781506317304.

- ^ "Professional Pigs". ABC News. Retrieved 9 August 2021.

- ^ "Man Choked to Death After Roach-Eating Contest". Nbcmiami.com. November 27, 2012. Retrieved June 16, 2014.

- ^ "Man dies during pie eating contest". The Guardian. July 18, 2013.

- ^ "Australian man dies during pub pie-eating competition". The Daily Telegraph.

- ^ "Australian man dies after eating chilli pie in pub pie eating contest". The Independent. July 19, 2013.

- ^ "Man Dies at South Dakota Hot Dog Eating Contest". The New York Times. July 7, 2014. Retrieved July 7, 2014.

- ^ "Contestant dies after choking on colonel's chicken during KFC's Rp 5 billion eating competition | Coconuts". coconuts.co/. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "Peserta Lomba Makan Ayam Tewas: Freedi Terkenal Sebagai Sosok yang Pintar | Kabar24". Bisnis.com (in Indonesian). 2016-03-13. Retrieved 2022-03-19.

- ^ "University Mourns Sorority Sister Who Died As A Result Of A Pancake-eating Contest".

- ^ Swerdloff, Alex (April 4, 2017). "Eating Competitions Killed Two People This Past Weekend". Vice. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Fresno man dies after competing in taco eating contest at Grizzlies baseball game". Fresno Bee. 2019. Retrieved August 14, 2019.

- ^ "Man dies after taco-eating contest in California". The Guardian. August 15, 2019. Retrieved November 6, 2019.

- ^ "Woman chokes to death during cake eating competition, witness says she "shoveled the lamington into her mouth with no restraint"". Newsweek. January 26, 2020.

- ^ Bedo, Stephanie (January 26, 2020). "Video emerges from fatal Aus Day contest". The Cairns Post.

- ^ "Woman dies during Australia Day lamington-eating competition". adelaidenow. January 26, 2020.

- ^ "Subscribe to The Chronicle". www.thechronicle.com.au.

- ^ Haggerty, Nancy. "Tufts lacrosse player Madie Nicpon, 20, dies after accident at hot dog eating contest". USA TODAY. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ Richardson, Rhondella (2021-10-20). "Local college student-athlete chokes to death during eating contest for charity". WCVB. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ "Student from NY dies after choking during hot dog eating contest". FOX 5 NY. 2021-10-21. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ Wong, Wilson (21 October 2021). "Tufts University lacrosse player dies after choking during hot dog eating contest, authorities say". NBC News. Retrieved 2021-10-22.

- ^ "Россиянка подавилась во время конкурса по поеданию блинов и умерла". NTV Russia (in Russian). 2023-02-26. Retrieved 2023-02-26.

- ^ "Natalie Buss choked in Beddau RFC marshmallow eating contest". BBC News. 18 October 2023.

Further reading

[edit]- Eat This Book (2006)

- Horsemen of the Esophagus (2006)

- A Short History of the American Stomach (2008, Frederick Kaufman)

- Clemens Berger: Die Wettesser. Roman, Skarabäus 2007 (The Competitive Eaters. A Novel)

External links

[edit]- EatFeats - competitive eating blog, database & calendar eatfeats.com

- All Pro Eating Promotions Archived 2010-07-14 at the Wayback Machine CompetitiveEaters.com