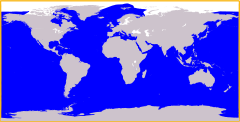

Cosmopolitan distribution

In biogeography, a cosmopolitan distribution is the range of a taxon that extends across most or all of the surface of the Earth, in appropriate habitats; most cosmopolitan species are known to be highly adaptable to a range of climatic and environmental conditions, though this is not always so. Killer whales (orcas) are among the most well-known cosmopolitan species on the planet, as they maintain several different resident and transient (migratory) populations in every major oceanic body on Earth, from the Arctic Circle to Antarctica and every coastal and open-water region in-between. Such a taxon (usually a species) is said to have a cosmopolitan distribution, or exhibit cosmopolitanism, as a species; another example, the rock dove (commonly referred to as a 'pigeon'), in addition to having been bred domestically for centuries, now occurs in most urban areas around the world.

The extreme opposite of a cosmopolitan species is an endemic (native) species, or one that is found only in a single geographical location. Endemism usually results in organisms with specific adaptations to one particular climate or region, and the species would likely face challenges if placed in a different environment. There are far more examples of endemic species than cosmopolitan species; one example being the snow leopard, a species found only in Central Asian mountain ranges, an environment to which the cats have adapted over millions of years.[1]

Qualification

[edit]The caveat "in appropriate habitat" is used to qualify the term "cosmopolitan distribution", excluding in most instances polar regions, extreme altitudes, oceans, deserts, or small, isolated islands.[2] For example, the housefly is highly cosmopolitan, yet is neither oceanic nor polar in its distribution.[3]

Related terms and concepts

[edit]The term pandemism also is in use, but not all authors are consistent in the sense in which they use the term; some speak of pandemism mainly in referring to diseases and pandemics, and some as a term intermediate between endemism and cosmopolitanism, in effect regarding pandemism as subcosmopolitanism. This means near cosmopolitanism, but with major gaps in the distribution, say, complete absence from Australia.[4][5] Terminology varies, and there is some debate whether the true opposite of endemism is pandemism or cosmopolitanism.[6]

Oceanic obstacles

[edit]A related concept in biogeography is that of oceanic cosmopolitanism and endemism. Rather than allow ubiquitous travel, the World Ocean is complicated by physical obstacles such as temperature gradients.[7] These prevent migration of tropical species between the Atlantic and Indian/Pacific oceans.[8] Conversely, the Northern marine regions and Southern Ocean are separated by the tropics, too warm for many species to traverse.

Ecological delimitation

[edit]Another aspect of cosmopolitanism is that of ecological limitations. A species that is apparently cosmopolitan because it occurs in all oceans might in fact occupy only littoral zones, or only particular ranges of depths, or only estuaries, for example. Analogously, terrestrial species might be present only in forests, or mountainous regions, or sandy arid regions or the like. Such distributions might be patchy, or extended, but narrow. Factors of such a nature are taken widely for granted, so they seldom are mentioned explicitly in mentioning cosmopolitan distributions.

Regional and temporal variation in populations

[edit]Cosmopolitanism of a particular species or variety should not be confused with cosmopolitanism of higher taxa. For example, the family Myrmeleontidae is cosmopolitan in the sense that every continent except Antarctica is home to some indigenous species within the Myrmeleontidae, but nonetheless no one species, nor even genus, of the Myrmeleontidae is cosmopolitan. Conversely, partly as a result of human introduction of unnatural apiculture to the New World, Apis mellifera probably is the only cosmopolitan member of its family; the rest of the family Apidae have modest distributions.

Even where a cosmopolitan population is recognised as a single species, such as indeed Apis mellifera, there generally will be variation between regional sub-populations. Such variation commonly is at the level of subspecies, varieties or morphs, whereas some variation is too slight or inconsistent for formal recognition.

For an example of subspecific variation, consider the East African lowland honey bee (Apis mellifera scutellata)—best known for being hybridized with various European subspecies of the western honey bee to create the so-called "African killer bee"—and the Cape bee, which is the subspecies Apis mellifera capensis; both of them are in the same cosmopolitan species Apis mellifera, but their ranges barely overlap.

Other cosmopolitan species, such as the house sparrow and osprey, present similar examples, but in yet other species there are less familiar complications: some migratory birds such as the Arctic tern occur from the Arctic to the Southern Ocean, but at any one season of the year they are likely to be largely in passage or concentrated at only one end of the range. Also, some such species breed only at one end of the range. Seen purely as an aspect of cosmopolitanism, such distributions could be seen as temporal, seasonal variations.

Other complications of cosmopolitanism on a planet too large for local populations to interbreed routinely with each other include genetic effects such as ring species, such as in the Larus gulls,[9] and the formation of clines such as in Drosophila.[10]

Examples

[edit]Cosmopolitan distributions can be observed both in extinct and extant species. For example, Lystrosaurus was cosmopolitan in the Early Triassic after the Permian-Triassic extinction event.[11]

In the modern world, the orca, the blue whale, and the great white shark all have cosmopolitan distribution, extending over most of the Earth's oceans. The wasp Copidosoma floridanum is another example, as it is found around the world. Other examples include humans, cats, dogs, the western honey bee, brown rats, the foliose lichen Parmelia sulcata, and the mollusc genus Mytilus.[12] The term can also apply to some diseases. It may result from a broad range of environmental tolerances[13][14] or from rapid dispersal compared to the time needed for speciation.[15]

See also

[edit]References

[edit]- ^ Z. Jack Tseng; Xiaoming Wang; Graham J. Slater; Gary T. Takeuchi; Qiang Li; Juan Liu; Guangpu Xie (2014). "Himalayan Fossils of the Oldest Known Pantherine Establish Ancient Origin of Big Cats". Proceedings: Biological Sciences. 281 (1774): 1–7. JSTOR 43600250.

- ^ Encyclopedia of Ecology and Environmental Management. John Wiley & Sons. 15 July 2009. p. 164. ISBN 978-1-4443-1324-6.

- ^ Richard C. Russell; Domenico Otranto; Richard L. Wall (2013). The Encyclopedia of Medical and Veterinary Entomology. CABI. p. 157. ISBN 978-1-78064-037-2.

- ^ Michael G. Simpson (19 July 2010). Plant Systematics. Academic Press. p. 720. ISBN 978-0-08-092208-9.

- ^ D. A. T. Harper; T. Servais (27 January 2014). Early Palaeozoic Biogeography and Palaeogeography. Geological Society of London. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-86239-373-8.

- ^ Eduardo H Rapoport (22 October 2013). Areography: Geographical Strategies of Species. Elsevier. p. 251. ISBN 978-1-4831-5277-6.

- ^ Waters, Jonathan M. (July 2008). "Marine biogeographical disjunction in temperate Australia: historical landbridge, contemporary currents, or both?". Diversity and Distributions. 14 (4): 692–700. Bibcode:2008DivDi..14..692W. doi:10.1111/j.1472-4642.2008.00481.x. ISSN 1366-9516.

- ^ Zarzyczny, Karolina M.; Rius, Marc; Williams, Suzanne T.; Fenberg, Phillip B. (March 2024). "The ecological and evolutionary consequences of tropicalisation" (PDF). Trends in Ecology & Evolution. 39 (3): 267–279. Bibcode:2024TEcoE..39..267Z. doi:10.1016/j.tree.2023.10.006. ISSN 0169-5347. PMID 38030539.

- ^ Werner Kunz (2 August 2013). Do Species Exist: Principles of Taxonomic Classification. Wiley. p. 211. ISBN 978-3-527-66426-9.

- ^ Costas B. Krimbas; Jeffrey R. Powell (21 August 1992). Drosophila Inversion Polymorphism. CRC Press. p. 23. ISBN 978-0-8493-6547-8.

- ^ Sahney, S.; Benton, M. J. (2008). "Recovery from the most profound mass extinction of all time". Proceedings of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences. 275 (1636): 759–65. doi:10.1098/rspb.2007.1370. PMC 2596898. PMID 18198148.

- ^ Ian F. Spellerberg; John William David Sawyer, eds. (1999). "Ecological patterns and types of species distribution". An Introduction to Applied Biogeography. Cambridge University Press. pp. 108–132. ISBN 978-0-521-45712-5.

- ^ S. Kustanowich (1963). "Distribution of planktonic foraminifera in surface sediments of the south-west Pacific". New Zealand Journal of Geology and Geophysics. 6 (4): 534–565. doi:10.1080/00288306.1963.10420065.

- ^ D. B. Williams (1971). "The distribution of marine dinoflagellates in relation to physical and chemical conditions". In B. M. Funnell; W. R. Riedel (eds.). The Micropalaeontology of Oceans: Proceedings of the Symposium held in Cambridge from 10 to 17 September 1967 under the title 'Micropalaeontology of Marine Bottom Sediments'. Cambridge University Press. pp. 91–95. ISBN 978-0-521-18748-0.

- ^ Judit Padisák (2005). "Phytoplankton". In Patrick E. O'Sullivan; Colin S. Reynolds (eds.). Limnology and Limnetic Ecology. The Lakes Handbook. Vol. 1. Wiley-Blackwell. pp. 251–308. ISBN 978-0-632-04797-0.

External links

[edit] The dictionary definition of cosmopolitan at Wiktionary

The dictionary definition of cosmopolitan at Wiktionary