David Winters (choreographer)

David Winters | |

|---|---|

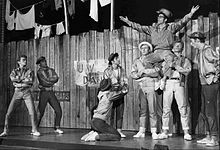

Winters in the 1960s | |

| Born | David Weizer April 5, 1939 London, England |

| Died | April 23, 2019 (aged 80) Fort Lauderdale, Florida, U.S. |

| Resting place | Mount Sinai Memorial Park Cemetery |

| Citizenship | United Kingdom United States |

| Occupations |

|

| Years active | 1954–2019 |

David Winters (April 5, 1939 – April 23, 2019) was an English-born American actor, dancer, choreographer, producer, distributor, director and screenwriter. At a young age, he acted in film and television projects such as Lux Video Theatre, Naked City; Mister Peepers, Rock, Rock, Rock, and Roogie's Bump. He received some attention in Broadway musicals for his roles in West Side Story (1957) and Gypsy (1959). In the film adaptation of West Side Story (1961) he was one of the few to be re-cast. It became the highest grossing motion picture of that year, and won 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.

Winters became a dance choreographer. On films, he choreographed several projects with Elvis Presley and Ann-Margret starting with Viva Las Vegas (1964). Other dance choreography credits include T.A.M.I. Show (1964), Send Me No Flowers (1964), Billie (1965), A Star Is Born (1976), etc. On television, he was frequently seen with his troupe on a variety of shows choreographing popular dances of the 1960s. At the Emmy Awards, for the television special Movin' with Nancy (1967), his choreography was nominated in the category Special Classification of Individual Achievements.

In the 1970s, Winters ran Winters-Rosen a production house, where he produced, directed, and choreographed television specials. Some of these credits are The Ann-Margret Show (1968), Ann-Margret: From Hollywood With Love (1969), Raquel! (1970), Once Upon a Wheel (1971), Timex All-Star Swing Festival (1972), etc. In films, he directed Alice Cooper: Welcome to My Nightmare (1976), The Last Horror Film (1982), Thrashin' (1986), etc. From the 1980s to the 1990s, Winters ran Action International Pictures where he would produce, distribute and sometime direct action oriented films. From the 2000s to his death in 2019, Winters continued to produce and direct.

Early life

[edit]Winters was born David Weizer in London, England, the son of Jewish parents Sadie and Samuel Weizer. His family relocated to the United States in 1953. He became a naturalized United States citizen in 1956.[1] Winters was interested in dancing at an early age.[2]

Career

[edit]Early 1950s-1967: Early roles, stage musicals, and dance choreography

[edit]At age 12, Winters was shining shoes to pay for dance classes afraid his mother would not approve. She eventually caught him and made a deal to make him stop: if he did his bar mitzvah, she would bring him to dance classes.[2] That same year, Winters was spotted by a talent agent while dancing in a Manhattan restaurant. From this point he began acting and dancing on television. By the age of 14 he had worked with Jackie Gleason, Martha Raye, Mindy Carson, Sarah Churchill, Wally Cox, George Jessel, Ella Raines, Paul Douglas, and Perry Como. He also was heard on radio plays with Donald Cook and Joseph Cotten. It led him to act in over 15 television shows during a span of 10 years, including Lux Video Theatre, Naked City, The Red Buttons Show, Mister Peepers, etc.[3]

In 1954, Winters acted in the film Roogie's Bump.[4] That year he performed in the first Broadway revival of On Your Toes, directed by George Abbott and choreographed by George Balanchine. It opened on October 11, 1954, at the 46th Street Theatre, where it ran for 64 performances.[5]

On November 23 of that year he acted in another Broadway play called Sandhog.[6] In the musical, Winters alongside Yuriko, Eliot Feld, Muriel Mannings, and Betty Ageloff played a group of kids. Paul Affelder of The Brooklyn Eagle praised all the performances, and found the kids talented.[7]

In 1956 he acted in Rock, Rock, Rock!.[8]

In 1957, he acted in Shinbone Alley. The Broadway production opened on April 13, 1957, at The Broadway Theatre and closed on May 25, 1957, after 49 performances.[9] Later that year, he played the role of Baby John in the original Broadway production of West Side Story.[10] Conceived, directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins, it ran for 732 performances before going on tour. The production was nominated for six Tony Awards including Best Musical.[11]

On May 21, 1959, he starred as Yonkers in the original production of Gypsy.[12] The show was produced by David Merrick and directed and choreographed by Jerome Robbins Critic Frank Rich has referred to it as one of the more influential stagings of a musical in American theatrical history.[13] The original production received eight Tony Award nominations, including Best Musical. It closed on March 25, 1961, after 702 performances and two previews.[14]

In 1960, he acted in the Broadway musical One More River.[15]

In 1961, he appeared as A-Rab in the movie version of West Side Story directed by Robert Wise and Jerome Robbins.[16] He and Carole D'Andrea, Jay Norman, Tommy Abbott, William Bramley and Tony Mordente were the only actors to have been cast in both the original Broadway show and the motion picture. The film was the highest grossing motion picture of that year, going on to win 10 Academy Awards, including Best Picture.[17]

During that time and moving forward to 1967, he acted regularly on television, he was seen in 77 Sunset Strip, Perry Mason, The Dick Powell Show, and more.[18][additional citation(s) needed]

On January 30, 1963, the play Billy Liar made its American premiere with Winters in the title role.[19] Margaret Harford of the Los Angeles Times liked the acting and said that Winters played the role with "coltish swagger".[20]

In 1964, he choreographed George Sidney's Viva Las Vegas starring Elvis Presley and Ann-Margret.[21] Ann-Margret, who was his student at the time, recommended him for the job.[22] That year Winters choreographed Norman Jewison's Send Me No Flowers,[23] Don Weis' Pajama Party,[24] and Steve Binder's T.A.M.I. Show.[25] T.A.M.I. Show would go on to be deemed "culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant" by the United States Library of Congress and selected for preservation in 2006 in the National Film Registry.[26] He also had a role in the film The New Intern.[27] On September 21, the variety show Shindig! premiered where Winters served as a choreographer.[28]

In 1965, he choreographed two musicals starring Elvis Presley: Boris Sagal's Girl Happy and Norman Taurog's Tickle Me.[29][30] He also choreographed two Ann-Margret films: Bus Riley's Back in Town and Kitten with a Whip.[31] Another choreographer credit was Don Weis' Billie.[32] That year, he started to perform on television with his troupe, named the David Winters Dancers.[33] That year, on the tv show Hullabaloo, he choreographed popular dances of the 1960s, including the Watusi, and originated the Freddy.[34][35]

In 1966, he co-produced and choreographed the Lucille Ball television special Lucy in London.[36][37] Also that year he acted in The Crazy-Quilt by John Korty,[38] and The David Winters Dancers also appeared in the television special MJ's.[39] Finally he choreographed two more Ann-Margret films Boris Sagal's Made in Paris,[40] and George Sidney's The Swinger.[41]

In 1967, Winters directed two episodes of the television show The Monkees.[42] He choreographed Elvis Presley in Easy Come, Easy Go.[43] With the David Winters Dancers, he appeared on the television special Go.[44] That year, he was an associate director for the Broadway play Of Love Remembered, directed by Burgess Meredith.[45] Also in 1967, for his choreography on the Nancy Sinatra television special Movin' with Nancy,[46] he received an Emmy nomination in the category Special Classification of Individual Achievements.[47]

1968 to 1986: Subsequent choreography, producing and directing

[edit]In 1968, he co-founded the production company Winters/Rosen which specialized in television specials.[48][49] He choreographed and directed The Ann-Margret Show.[50] That year, separately from Winters/Rosen, he choreographed and performed with his troupe on the television special Monte Carlo: C'est La Rose, hosted by Princess Grace Kelly.[51]

In 1969, Winters directed and choreographed Ann-Margret: From Hollywood With Love (for which Winters received an Emmy nomination for dance choreography).[52] Also that year, he produced and choreographed The Spring Thing.[53]

On April 26, 1970 CBS released Raquel Welch's first television special Raquel!, Winters produced, directed and choreographed.[54] On the day of the premiere, the show received a 51% share on the National ARB Ratings and an overnight New York Nielsen Rating of 58% share.[55]

In 1971, he produced and directed Once Upon a Wheel, a documentary on auto racing.[56] It is hosted and narrated by actor Paul Newman.[57] Winters said that at the time Newman had publicly stated he didn't want to do television and turned it down for this reason until he pitched his vision to him.[58] The project marked Newman's return to television after a decade long absence,[59] and his first time as the lead of a program.[60] During post-production, Winters said that Newman, who liked what he saw, gave him the idea to add some footage to sell it as a theatrical film worldwide.[61] Upon its release, the documentary generally received good reviews for its directing, pace, photography, music, and human interest stories.[62][63][64][65][66][67][68][69][70][71]

That same year, he was an executive producer for The 5th Dimension's television special The 5th Dimension Traveling Sunshine Show.[72][73]

In 1972, he produced, directed and choreographed the television special The Special London Bridge Special, starring Tom Jones, and Jennifer O'Neill.[74] That year, he produced Timex All-Star Swing Festival (which won the Peabody Award and a Christopher Award for Winters as its producer), a live concert with performances by jazz musicians Ella Fitzgerald, Duke Ellington, Dave Brubeck, Benny Goodman, Gene Krupa, etc.[75]

In 1973, he directed, choreographed and produced the television movie Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde, starring Kirk Douglas.[76] At the Emmy Awards it was nominated for outstanding achievement in makeup, costume design, and music direction.[77]

In 1975, Winters directed the Alice Cooper concert film Alice Cooper: Welcome to My Nightmare.[78] That same year, he produced the comedy Linda Lovelace for President.

In 1976, he choreographed Frank Pierson's A Star Is Born, starring Barbra Streisand.[79]

The following year he choreographed credits 22 episodes of TV show Donny & Marie.[citation needed] That year he also served as a creative consultant on Don Taylor's The Island of Dr. Moreau.[80]

In 1978, he choreographed Steve Binder's Star Wars Holiday Special.[81]

In 1979 Winters directed the tennis sport comedy Racquet, starring Bert Convy.[82] That same year, he choreographed Mark L. Lester's Roller Boogie.[83] Also in 1979, Diana Ross In Concert premiered on television, Winters conceived and directed the stage production.[84]

In 1980. Winters directed and choreographed the stage show Goosebumps.[85]

In 1981, he choreographed and was creative consultant for the Diana Ross television special Diana.[86]

In 1982, he produced, directed, wrote, and co-starred in the horror comedy The Last Horror Film, starring Joe Spinell and Caroline Munro.[87][88] It played in film festivals.[89] At the Sitges Film Festival it was part of their official selection, and won best cinematography.[90] At the Saturn Awards the film was nominated for Best International film and Mary Spinell was nominated for best supporting actress.[91]

In 1984 he directed the documentary That Was Rock, hosted by Chuck Berry,[92] and a television adaptation of Steadfast Tin Soldier.[93] Also that year he worked as an artistic adviser on the film Blame it on the Night.[94]

In 1985, he directed Girls of Rock & Roll.[95]

In 1986, Winters directed the sports film Thrashin', starring Josh Brolin, and Pamela Gidley. Set in Los Angeles, it's about Cory (Brolin), a teenage competitive skateboarder, and his romance with Chrissy (Gidley).[96] With a notable soundtrack, the film maintains a following.[citation needed] Prior to the casting of Brolin, Winters wanted Johnny Depp to play Cory.[97][98] That same year, directed the action film Mission Kill, with Robert Ginty.[99]

1987 to 2019: Later works

[edit]In 1987, Winters opened the production company, Action International Pictures. He hired director David A. Prior, with whom he would work regularly moving forward. That year they released Deadly Prey, Aerobicide, and Mankillers.[100][101][102]

In 1988, he directed the action film Rage to Kill starring James Ryan.[103] That year also saw the release of the space opera science fiction film Space Mutiny.[104] While being the credited director, Winters disowned the film. According to him, upon the first shooting day, he was informed that his father had passed. Being emotionally troubled and with a funeral to attend, Winters was unable to perform his duties and passed it on to his assistant director Neal Sundstorm. However, he was informed that the investors had agreed to the film only with Winters as its director, and could face litigation if he withdrew, hence the credit.[105] The film has the reputation of being an amusing ,unintentionally funny, and campy B-movie.[106][107][108] That year, Winters produced Dead End City,[109] Death Chase,[110] Night Wars,[111] and Phoenix The Warrior.[112]

In 1989, the action film Code Name Vengeance was released, with Winters directing and producing.[113] Robert Ginty played the lead.[114] Winters would go on to produce The Bounty Hunter (1989),[115] Order of Eagle (1989),[116] Future Force (1989),[117] Time Burst - The Final Alliance (1989),[118] Deadly Reactor (1989),[119] Hell on the Battleground (1989),[120] Jungle Assault (1989),[121] The Revenger (1990),[122] Fatal Skies (1990),[123] Future Zone (1990),[124] Deadly Dancer (1990),[125] Operation Warzone (1990),[126] Rapid Fire (1990),[127] The Shooters (1990),[128] The Final Sanction (1990),[129] Lock 'n' Load (1990),[130] Born Killer (1990),[131] Invasion Force (1990),[132] Firehead (1991),[133] Dark Rider (1991),[134] Raw Nerve (1991),[135] Maximum Breakout (1991),[136] Cop-Out (1991),[137] Presumed Guilty (1991),[138] The Last Ride (1991),[139] White Fury (1991),[140] Center of the Web (1992),[141] Armed for Action (1992),[142] Blood on the Badge (1992),[143] and Double Threat (1993).[144]

In 1993, AIP was re-branded as West Side Studios with the intent to take a mainstream direction. Under that banner, he produced Night Trap (1993),[145][146] Raw Justice (1994),[147] The Dangerous (1995),[148] and Codename: Silencer (1995).[149]

In 1999, Winters produced Rhythm & Blues.[150]

In 2002, he produced, directed, and co-starred the comedy film Welcome 2 Ibiza, which won the Bangkok Film Festival Audience Award.[151][89]

In 2003, he produced the horror film Devil's Harvest.[152]

In 2005, he produced period filmThe King Maker.[89]

In 2006, Winters acted in Kevin Connor's mini-series Blackbeard.[153]

In 2012, Winters acted in the art house film, Teddy Bear.[154]

In 2015, Dancin': It's On!, a dance film, premiered which Winters directed. For this project, he said he reconnected with his original passion for dancing.[155] The film stars winners and runners-up of the tv shows, So You Think You Can Dance, and Dancing with the Stars, with Witney Carson as its lead.[156]

In 2018, Winters released his memoir Tough Guys Do Dance.[157]

Death

[edit]Winters died on 23 April 2019 at the age of 80, from congestive heart failure.[158][159]

Personal life

[edit]Friends with rock singer Alice Cooper upon directing the Welcome to My Nightmare Tour in the mid 1970s, he hired ballerina Sheryl Goddard who became Cooper's wife.[160][161]

Winters lived with Linda Lovelace as her boyfriend following her divorce from her first husband. Their relationship lasted until 1976. She credited him for bringing culture in her life.[162]

Winters was married at least three times. He had a brother, a daughter, two sons, a stepson, and a granddaughter.[163]

Filmography

[edit]Awards and nominations

[edit]| Year | Award | Result | Category | Film or series |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1968 | Emmy Award | Nominated | Special Classification of Individual Achievements[164] | Movin' with Nancy |

| 1970 | Outstanding Achievement in Choreography[165] | Ann-Margret: From Hollywood with Love | ||

| 1971 | Best International Sports Documentary | Won | TV special[citation needed] | Once Upon a Wheel |

| World Television Festival Award | TV special[citation needed] | |||

| 1972 | Christopher Award | Won | TV special[citation needed] | Timex All Star Swing Festival (shared with Burt Rosen, Bernard Rothman, and Jack Wohl) |

| 2002 | Bangkok Film Festival | Won | Audience Award for Best Picture[citation needed] | Welcome 2 Ibiza |

| 2015 | WideScreen Film & Music Video Festival | Won | Best Director[156] | Dancin' It's On! |

Bibliography

[edit]- Winters, David (2018). Tough guys do dance. Pensacola, Florida: Indigo River Publishing. ISBN 978-1-948080-27-9.

References

[edit]- ^ "David Winters profile". Filmreference.com. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- ^ a b "Choreographer David Winters Opens Up About His New Film And His Love Of Fort Lauderdale". Fort Lauderdale Daily. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ "Flatbush boy, gaining fame on tv, is still a kid at home". The Brooklyn Daily Eagle. March 4, 1954. p. 7.

- ^ "Roogie's Bump | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "On Your Toes Broadway @ 46th Street Theatre – Tickets and Discounts". Playbill. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ "Sandhog Broadway @ Phoenix Theatre – Tickets and Discounts". Playbill. Retrieved April 23, 2019.

- ^ Affelder, Paul (December 5, 1954). "Music used generously in 'Sandhog' at the Phoenix". The Brooklyn Eagle. p. 30.

- ^ "Rock, Rock, Rock | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Shinbone Alley Broadway @ Broadway Theatre – Tickets and Discounts". Playbill. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ "Sondheim.com – Putting it together since 1994". www.sondheim.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ " West Side Story Broadway" IBDB.com, accessed October 15, 2016

- ^ "Sondheim.com – Putting it together since 1994". www.sondheim.com. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ Rich, Frank (November 17, 1989) The Hot Seat: Theater Criticism for The New York Times, 1980–1993. Random House. 1998. ISBN 0-679-45300-8.

- ^ Naden, Corinne J. (February 1, 2011). The Golden Age of American Musical Theatre: 1943–1965. Scarecrow Press. p. 81. ISBN 978-0-8108-7734-4.

- ^ "One More River Broadway @ Ambassador Theatre – Tickets and Discounts". Playbill. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Williams, Whitney (September 27, 1961). "West Side Story". Variety. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Grant, Barry Keith (2012). The Hollywood Film Musical. Wiley-Blackwell. p. 100. ISBN 9781405182539.

- ^ "Perry Mason | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ "Tickets on sale for 'Liar'". Los Angeles Evening Citizen News. January 23, 1963. pp. C-3.

- ^ Harford, Margaret (February 1, 1963). "'Billy Liar' in the U.S. bow at Stage Society". Los Angeles Times. pp. Part IV - 7.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Wakin, Daniel J. (May 24, 2019). "What They Left Behind: Legacies of the Recently Departed". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on June 25, 2023. Retrieved May 27, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved August 2, 2021.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Librarian of Congress Adds Home Movie, Silent Films and Hollywood Classics to Film Preservation List". Library of Congress, Washington, D.C. 20540 USA. Archived from the original on July 13, 2023. Retrieved July 13, 2023.

- ^ "The New Interns | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ "Today's Channel Check". Cincinnati Enquirer. September 21, 1964.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "Sons Of Three Famous Stars On 'Hullabaloo'". The Daily Times. Vol. LXI. February 6, 1965.

- ^ Crosby, Joan (April 11, 1965). "The 'Watusi' Has A Choreographer?". Santa Cruz Sentinel.

- ^ Smith, Gary (July 21, 1965). "All The Hullaballoo To Return". The Salina Journal.

- ^ Binder, Steve (2011). The Lucy Show The Official fifth season (DVD). Paramount. Event occurs at Lucy in London. ISBN 1-4157-5767-4. 097368207448.

- ^ "Lucy's 'London' Is Fun Special". Hartford Courant. Vol. CXXIX. October 23, 1966.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ "Television Log". Independent. Vol. 28. January 28, 1966.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "David Winters | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 19, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ "National TV Debut". The Argus. Vol. VIIII. April 18, 1967.

- ^ "Of Love Remembered Broadway @ ANTA Theatre – Tickets and Discounts". Playbill. Retrieved April 24, 2019.

- ^ Movin' with Nancy (DVD). Image Entertainment. 2000. 4895033723509.

- ^ "Movin' With Nancy". Television Academy. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ "Award-winning Producer Burt Rosen Dies". Television Academy. Retrieved October 7, 2018.

- ^ "TEC, TV Packager Enter Tie". Billboard. April 26, 1969.

- ^ Jones, Paul (December 1, 1968). "Goodies Aplenty On Tube Sunday". The Atlanta Constitution. Vol. 19.

- ^ "Princess Grace and the Weather". The Times. Vol. 68. February 24, 1968.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (June 6, 2013). Television Specials: 5,336 Entertainment Programs, 1936–2012, 2d ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1240-9.

- ^ Terrace, Vincent (June 6, 2013). Television Specials: 5,336 Entertainment Programs, 1936–2012, 2d ed. McFarland. ISBN 978-1-4766-1240-9.

- ^ Brown, Les (1971). ""Raquel!"". Television: The Business Behind the Box. Harcourt Brace Jovanovich. p. 187, 188. ISBN 978-0-15-688440-2.

- ^ Thomas, Bryan (September 5, 2015). "Happy Birthday today to Raquel Welch: Her 1970 primetime TV special will melt your mind!". Nightlife. Archived from the original on April 11, 2019. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Ingle, Zachary; Sutera, David M. (2013). Identity and Myth in Sports Documentaries: Critical Essays. Rowman & Littlefield. p. 170. ISBN 978-0-8108-8789-3.

- ^ Shull, Richard K. (April 17, 1971). "Teaches Stars to Drive". The Ithaca Journal.

- ^ Winters, David (2018). Tough guys do dance. Pensacola, Florida: Indigo River Publishing. pp. 2582–2670. ISBN 978-1-948080-27-9.

- ^ "'Once upon a wheel' Newman hosts program exploring facets of racings". Press-Telegram. 20: Tele-Vues: Five. April 18, 1971.

- ^ "'Once Upon a Wheel' is a first". The Town Talk. LXXXIX: Section B: Eleven. April 18, 1971.

- ^ Winters, David (2018). Tough guys do dance. Pensacola, Florida: Indigo River Publishing. pp. 2582–2670. ISBN 978-1-948080-27-9.

- ^ Gross, Ben (April 19, 1971). "The Diana Ross special tops weekend TV shows". Daily News. 52: 35.

- ^ Lowry, Cynthia (April 19, 1971). "'Once Upon a Wheel' is successful effort". Pottsville Republican. CLXXI: 19.

- ^ Anderson, Jack (April 20, 1971). "Auto race special exciting". The Miami Herald: 4–B.

- ^ Harris, Harry (April 19, 1971). "Diana Ross is supreme making people laugh". The Philadelphia Inquirer. 284: 15.

- ^ Bishop, Jerry (April 28, 1971). "Why can't Tv movie people tell the story of racing as it is?". Longview Daily News: 47.

- ^ Coffey, Jerry (April 20, 1970). "Southwest of 1914-15 setting for two shows". Forth Worth Star-Telegram: 6–A.

- ^ Hopkins, Tom (April 19, 1971). "ABC uses special as giant promotions". Dayton Daily News. 94: 52.

- ^ Greene, Jerry (April 20, 1971). "Tv Capture racing drama". Florida Today: 1C.

- ^ Newton, Dwight (April 19, 1971). "A career in crescendo". San Francisco Examiner: 19.

- ^ Dubrow, Rick (April 19, 1971). "Diana Ross, a complete act". The Windsor Star: 22.

- ^ The 5th Dimension Travelling Sunshine Show (DVD). V.I.E.W. Video. ISBN 0-8030-2323-5. 2323.

- ^ "It's Time to Take the 5th". Alexandria Daily Town Talk. Vol. LXXXIX.

- ^ Ellis, Lucy; Sutherland, Bryony (2000). Tom Jones: close up. London: Omnibus Press. ISBN 978-0-7119-7549-1.

- ^ "All-Star Swing Festival (1977) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Musical Version of Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde Stars Kirk Douglas". The Mexia Daily News. Vol. 74. April 3, 1973.

- ^ "Dr. Jekyll and Mr. Hyde". Television Academy. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ "Welcome To My Nightmare: Review". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "A Star Is Born | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Binder, Steve (1978). Star Wars Holiday Special (VHS). CBS FOX. OOP-O9.

- ^ "Racquet | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Roller Boogie | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Diana Ross In Concert (Laserdisc). Pioneer Artists. 1984. PA-84-070.

- ^ "TGIF The Great Index to Fun". The San Francisco Examiner. August 22, 1980. pp. E2.

- ^ NilesNL69 (February 12, 2016), Diana Ross 1981 TV-Special, retrieved May 14, 2019

{{citation}}: CS1 maint: numeric names: authors list (link) - ^ "Last Horror Film, The (1984) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "[Blu-ray Review] 'The Last Horror Film' is a Good Movie with a Bad Blu-ray – Bloody Disgusting". bloody-disgusting.com. January 12, 2016. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved October 3, 2018.

- ^ a b c "David Winters". Dance Mogul Magazine. July 1, 2012. Archived from the original on May 11, 2019. Retrieved May 11, 2019.

- ^ "Festival Archives - Sitges Film Festival - Festival Internacional de Cinema Fantàstic de Catalunya". sitgesfilmfestival.com. Archived from the original on August 15, 2020. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Cotter, Robert Michael "Bobb" (January 10, 2014). Caroline Munro, First Lady of Fantasy: A Complete Annotated Record of Film and Television Appearances. McFarland. ISBN 9780786491520.

- ^ Winters, David (1982). That Was Rock (VHS). Musik Media. M 434.

- ^ The Steadfast Tin Soldier (VHS). Video Treasures. 1988. ISBN 1-55529-315-8. 013132907802.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 29, 2019.

- ^ Winters, David (1985). Girls of Rock & Roll (VHS). Playboy. 0-1313-29370-3-8.

- ^ "AFI|Catalog". catalog.afi.com. Retrieved April 20, 2019.

- ^ Winters, David (1986). "Audio Commentary Track", Thrashin, DVD, MGM Home Video

- ^ Tyner, Adam (August 5, 1993). "Thrashin'". Retrieved September 29, 2008.

... something [which the cast] found so astonishing that they apparently called Depp's girlfriend in the middle of the commentary to find out if it's actually true.

- ^ "Mission Kill | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Mankillers Blu-ray". Blu-ray.com. September 13, 2016. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ "Bluray Movie Editions with David A. Prior (3)". Blu-ray.com. Retrieved December 25, 2016.

- ^ "Direct-to-Video Pioneer DAVID A. PRIOR – The Career Restrospective [sic]". We Are Movie Geeks. September 12, 2018. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ "Rage to Kill (1988) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Recent movies". The Philadelphia Inquirer. Vol. 320. April 6, 1989.

- ^ Winters, David (2018). Tough guys do dance. Pensacola, Florida: Indigo River Publishing. pp. 4348–4411. ISBN 978-1-948080-27-9.

- ^ Reagan, Danny (March 31, 1989). "Two from AIP, and a very weird one from Vestron". Abilene Reporter-News: 2C.

- ^ Mayo, Mike (April 26, 1989). "A foursome of farces from the far side". The Roanoke Times: Extra: 1.

- ^ Lounges, Tom (May 5, 1989). "Aliens, lasers stir excitement in science fiction release". The Times: C-6.

- ^ "Dead End City (1988) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Death Chase (1988) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Night Wars (1988) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Phoenix the Warrior (1988) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Code Name Vengeance (1989)". BFI. Archived from the original on April 27, 2019. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Winters, David (1989). Codename Vengeance (DVD). UK: Moonstone. 5 030462 012490.

- ^ "Bounty Hunter, The (1989) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Order of the Eagle (VHS). AIP Home Video. 1989. # A-7006.

- ^ "Future Force (1989) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Time Burst - The Final Alliance (1989) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Deadly Reactor (1989) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Hell on the Battleground (1989) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Jungle Assault (1989) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ The Revenger (VHS). AIP Home Video. 1990. # 7023.

- ^ Fatal Skies (VHS). AIP Home Video. 1990. # 7050.

- ^ "Future Zone (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Deadly Dancer (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ "Operation Warzone (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Rapid Fire (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Shooters, The (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Final Sanction, The (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Lock 'n' Load (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Born Killer (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Invasion Force (1990) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 7, 2019.

- ^ "Firehead | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Dark Rider (VHS). 20:20 Vision. 1991. NVT 13992.

- ^ Prouty (March 29, 1994). Variety TV REV 1991–92 17. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-0-8240-3796-3.

- ^ Maximum Breakout (VHS). AIP Home Video. 1991. 05276975623.

- ^ Cop-Out (VHS). US: AIP Home Video. 1991. # 7794.

- ^ "New On Video". Austin American-Statesman. January 6, 1991. p. 87.

- ^ "The Video Guide". Dayton Daily News. Vol. 115.

- ^ Prior, David A. (1991). White Fury (VHS). AIP Home Video. # 7055.

- ^ "Center Of The Web | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Armed For Action | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Blood On The Badge | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Double Threat | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Klein, Richard (February 26, 1993). "AIP renamed West Side Studios". Variety. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ "Mardi Gras For The Devil | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "Raw Justice | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ "The Dangerous | TV Guide". TVGuide.com. Retrieved April 10, 2019.

- ^ Grove, David (September 15, 2016). Jan-Michael Vincent: Edge of Greatness. BearManor Media.

- ^ "Rhythm & Blues (1999) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved May 8, 2019.

- ^ "Welcome 2 Ibiza (2002) - Overview - TCM.com". Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- ^ Dark Heaven/ Devils Harvest - Double Feature (DVD). 2005. 02157555405.

- ^ Marill, Alvin H. (October 11, 2010). Movies Made for Television: 2005–2009. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7659-0.

- ^ Dargis, Manohla (August 21, 2012). "'Teddy Bear,' With the Danish Bodybuilder Kim Kold". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Archived from the original on April 8, 2019. Retrieved April 8, 2019.

- ^ Simmons, Tony. "At long last, 'Dancin' to shine on local screens". Panama City News Herald. Archived from the original on April 9, 2019. Retrieved April 9, 2019.

- ^ a b Dancin' It's On! (DVD). Hannover House. 2014. HH4468.

- ^ Winters, David (June 11, 2018). Tough Guys Do Dance. Indigo River Publishing. ISBN 978-1-948080-27-9.

- ^ "The Original A-Rab, Director/Choreographer/Producer David Winters Has Passed On – Times Square Chronicles". April 24, 2019. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Wild, Stephanie. "Dancer and Choreographer David Winters Dies at Age 80". BroadwayWorld.com. Retrieved May 17, 2019.

- ^ Blabbermouth (April 25, 2019). "ALICE COOPER Pays Tribute To 'Welcome To My Nightmare' Concert Film Director DAVID WINTERS". BLABBERMOUTH.NET. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "Apr 23, 2019: David Winters, 'West Side Story' Actor and Rock Choreographer, Dies". Best Classic Bands. August 4, 2015. Retrieved November 3, 2023.

- ^ "Linda Lovelace dies in car crash". UPI. April 23, 2002. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ Sandomir, Richard (May 3, 2019). "David Winters, Energetic Dancer Turned Choreographer, Dies at 80". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved May 16, 2019.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners: Television Academy". Emmys.com. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

- ^ "Nominees/Winners: Television Academy". Emmys.com. Academy of Television Arts & Sciences. Retrieved April 26, 2019.

Works cited

[edit]- Rich, Frank (1989). The Hot Seat: Theater Criticism for The New York Times, 1980–1993. Random House. 1998. ISBN 978-0-679-45300-0

- Naden, Corinne J. (2011). The Golden Age of American Musical Theatre: 1943–1965. Scarecrow Press. ISBN 978-0-8108-7734-4

- Grant, Barry Keith (2012). The Hollywood Film Musical. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-1-4051-8253-9

- Ingle, Zachary; Sutera, David M. (2013). Identity and Myth in Sports Documentaries: Critical Essays. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-8108-8789-3

- Winters, David (2018). Tough guys do dance. Pensacola, Florida: Indigo River Publishing. ISBN 978-1-948080-27-9.

External links

[edit]- 1939 births

- 2019 deaths

- American male child actors

- American choreographers

- American male dancers

- American male film actors

- Jewish American male actors

- Film directors from Los Angeles

- American film producers

- American male screenwriters

- American male television actors

- American television directors

- American television producers

- Burials at Mount Sinai Memorial Park Cemetery

- English male child actors

- English choreographers

- English male dancers

- English male film actors

- English film directors

- English film producers

- English male musical theatre actors

- English male screenwriters

- English male television actors

- English television directors

- English television producers

- English-language film directors

- English emigrants to the United States

- English Jews

- Male actors from London

- 20th-century English businesspeople

- 21st-century American Jews