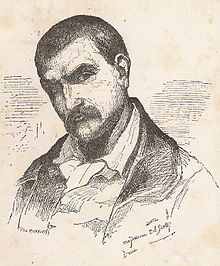

François Delsarte

François Alexandre Nicolas Chéri Delsarte (19 November 1811 – 20 July 1871) was a French singer, orator, and coach. Though he achieved some success as a composer, he is chiefly known as a teacher in singing and declamation (oratory).

Applied aesthetics

[edit]Delsarte was born in Solesmes, Nord. He became a pupil at the Paris Conservatory, was for a time a tenor in the Opéra Comique, and composed a few songs. While studying singing at the Conservatoire, he became unsatisfied with what he felt were arbitrary methods for teaching acting. He began to study how humans moved, behaved and responded to various emotional and real-life situations. By observing people in real life and in public places of all kinds, he discovered certain patterns of expression, eventually called the Science of Applied Aesthetics. This consisted of a thorough examination of voice, breath, movement dynamics, encompassing all of the expressive elements of the human body. His hope was to develop an exact science of the physical expression of emotions, but he died before he had achieved his goals.

Delsarte System

[edit]Delsarte coached preachers, painters, singers, composers, orators and actors in the bodily expression of emotions. His goal was to help clients connect their inner emotional experience with the use of gesture. Delsarte categorized ideas related to how emotions are expressed physically in the body into various rules, ‘laws’ or ‘principles.’ These laws were organized by Delsarte in charts and diagrams. Delsarte did not teach systematically but rather through inspiration of the moment, and left behind no publications on his lessons. In America, Delsarte's theories were developed into what became known as the (American) Delsarte System.

Influence and impact

[edit]

Delsarte's ideas were influential to the physical culture movement in the late 19th century.[1] Delsarte intended his work for the performing arts, including the theatre, and one of his many students (who also included orators and teachers) was Sarah Bernhardt.[1]

Delsarte never wrote a text explaining his method, and neither did his only protégé, the American actor Steele MacKaye, who brought his teacher's theories to America in lecture demonstrations he delivered in New York and Boston in 1871. However, MacKaye's student Genevieve Stebbins continued in their footsteps by developing a system of 'harmonic gymnastics',[1] and in 1886 she published a book building on the foundation of Delsarte's theories titled The Delsarte System of Expression, which became a major success with six editions (as well as numerous copycat publications). Stebbins also lectured extensively on Delsarte's theories, and displayed them (in conjunction with harmonic gymnastics) by statue-posing and performing so-called 'pantomimes' illustrating a poem, story or concept, thereby bringing Delsarte's work closer to dance.[1] According to a contemporary description, Stebbins's statue poses, spiralling from head to toe, would "flow gracefully onward from the simple to complex... commencing with a simple attitude, and continuing with a slow, rhythmic motion of every portion of the body."[2] Although she did not describe herself as a dancer, from 1890 at the latest she started to perform actual dances as well as poses.[2]

There was a renewed interest in Delsartism in the 1890s in Europe.[1] The principles of Delsarte were incorporated into expressionist dance and modern dance more generally through the influence of Isadora Duncan[a] and the Denishawn school of Ruth St. Denis and Ted Shawn.[1][3] While St. Denis claimed a performance by Stebbins inspired her to dance, Shawn consciously embodied the Delsarte System in his work (and his book Every Little Movement (1954) is a key English-language text on the subject).[3] As well as permeating the entire modern-dance movement in America,[4] Delsartian influence may also be felt in German Tanztheater, through the work of Rudolf Laban[b] and Mary Wigman.[1]

Ironically, it was the great success of the Delsarte System that was also its undoing. By the 1890s, it was being taught everywhere, and not always in accordance with the emotional basis that Delsarte originally had in mind. No certification was needed to teach a course with the name Delsarte attached, and the study regressed into empty posing with little emotional truth behind it. Stephen Wangh concludes, "it led others into stereotyped and melodramatic gesticulation, devoid of the very heart that Delsarte had sought to restore."[7]

Family

[edit]Delsarte was the uncle of composer Georges Bizet and grandfather of painter Thérèse Geraldy.

References

[edit]This article incorporates text from a publication now in the public domain: Gilman, D. C.; Peck, H. T.; Colby, F. M., eds. (1905). New International Encyclopedia (1st ed.). New York: Dodd, Mead. {{cite encyclopedia}}: Missing or empty |title= (help)

- ^ a b c d e f g h Thomas, Helen (1995). Dance, Modernity, and Culture: Explorations in the Sociology of Dance. Psychology Press. pp. 48–52. ISBN 978-0-415-08793-3.

- ^ a b Ruyter, Nancy Lee Chalfa (1996). "The Delsarte Heritage". Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research. 14 (1): 62–74. doi:10.2307/1290825. ISSN 0264-2875. JSTOR 1290825.

- ^ a b c Legg, Joshua (2011). Introduction to Modern Dance Techniques. Princeton Book Company. pp. 1–4, 8–12. ISBN 978-0-87127-325-3.

- ^ Reynolds, Nancy; McCormick, Malcolm (2003). No Fixed Points: Dance in the Twentieth Century. Yale University Press. p. 11. ISBN 978-0-300-09366-7.

- ^ Hodgson, John (2016) [2001]. Mastering Movement: The Life and Work of Rudolf Laban. Routledge [Methuen Drama]. pp. 64–67. ISBN 978-1-135-86086-8.

- ^ Preston-Dunlop, Valerie (2008). Rudolf Laban: An Extraordinary Life. London: Dance Books. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-1-85273-124-3.

- ^ Wangh, Stephen. (2000). An Acrobat of the Heart: A Physical Approach to Acting Inspired by the Work of Jerzy Grotowski. New York: Vintage Books. p. 32. ISBN 0-375-70672-0

Notes

[edit]- ^ Duncan's official denial of any familiarity with Desarte's work failed to convince her biographers as plausible: for example, in an interview of 1898 she extolled his mastery of the principles of flexibility and bodily lightness, and her aesthetic pronouncements on the "inner man" in relation to the body closely echoed Delsarte's own.[3]

- ^ Laban is said to have acknowledged the stimulus of Delsarte's work and appears to have studied what he loosely referred to as "Delsarte mime" while in Paris between 1900 and 1908;[5] the evolution of his own movement theory seems to reflect familiarity with Delsartian ideas.[6]

Further reading

[edit]- Franck Waille, Christophe Damour (dir.), François Delsarte, une recherche sans fin, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2015.

- Ted Shawn, Every Little Movement: A Book about François Delsarte, 1954

- Franck Waille (dir.), Trois décennies de recherches européennes sur François Delsarte, Paris, L'Harmattan, 2011.

- Alain Porte, François Delsarte, une anthologie, Paris, IPMC, 1992.

- Williams, Joe, A Brief History of Delsarte

- Franck Waille, Corps, arts et spiritualité chez François Delsarte (1811–1871). Des interactions dynamiques, PhD in history, Lyon, Université Lyon 3, 2009, 1032 pages + CDROM of annexes (manuscripts, interview of Joe Williams, video reconstitutions of body exercises) (the last and longer chapter of this thesis concerns Delsarte training for the body).

- Nancy Lee Chalfa Ruyter, "The Delsarte Heritage," Dance Research: The Journal of the Society for Dance Research, 14, no. 1 (Summer, 1996), pp. 62–74.

- Delsarte system of expression, by Genevieve Stebbins; public-domain, online version on Internet Archive.

- Eleanor Georgen, The Delsarte system of physical culture (1893) (Internet Archive)

- Carolina W. Le Farve. (1894). Physical Culture Founded on Delsartean Principles. New York: Fowler & Wells.

- Edward B. Warman. Gestures and Attitudes: Exposition of the Delsarte Philosophy of Expression, Practical and Theoretical, 1892.