Gallo-Roman enclosure of Tours

The southern wall of the enclosure and the Petit-Cupidon tower in the background. | |

| |

| 47°23′42″N 0°41′40″E / 47.39500°N 0.69444°E | |

| Location | Tours, Touraine, Indre-et-Loire, France |

|---|---|

| Type | Fortified enclosure |

| Completion date | 4th century |

| Partially listed as MH (1927)[1] | |

The Gallo-Roman enclosure of Tours is a wall surrounding the city of Civitas Turonorum (the cathedral quarter of the current city of Tours) and was constructed during the Late Roman Empire. It is commonly referred to as the "castrum enclosure." Only the remaining Gallo-Roman construction in Tours is accessible to the public. The enclosure has been designated a historical monument since 1927.

The structure was erected in the early years of the 4th century in the northeastern sector of the open city that had been established during the High Empire era. This construction was undertaken in response to the prevailing insecurity experienced in Gaul during this period. Many other cities subsequently adopted similar defensive measures. However, the implementation of this particular structure was not carried out hastily. This enclosure, which had a perimeter of 1,245 meters, was constructed using recycled materials sourced from existing buildings. The structure was supported by the amphitheater of Tours, which was converted into a monumental gate in the south of the new city. Approximately fifteen towers reinforced it, and several gates and posterns pierced it. The Loire River bathed its northern wall. When Tours expanded and built new enclosures in the 12th century and two centuries later, the castrum wall served as the base for the eastern part of the new constructions.

The meticulous archaeological excavations conducted from 1974 to 1978 on the site of the Tours castle (referred to as "site 3" by archaeologists) were followed by exhaustive studies in the early 1980s. These studies were completed at the end of the 20th century and the beginning of the 21st century, providing a comprehensive understanding of the architectural features of the site. However, considerable uncertainty persists regarding the structuring of space within the Cité, the nine hectares enclosed by the enclosure, and the number and social characteristics of its residents. A hypothesis is emerging that sees the northern half of the space inhabited by "civilians", including representatives of the administrative authority, while the southern half was reserved for religious individuals around the episcopal pole. It seems reasonable to posit that the city of Tours of the Late Empire did not confine itself to this fortified enclosure. However, the organization of the space outside the walls remains shrouded in obscurity.

Geographical and historical context[edit]

Local constraints[edit]

At the beginning of the 3rd century, the city of Tours, founded in the first half of the 1st century AD, had already undergone significant changes. Like two-thirds of the cities in northern Gaul,[2] it gradually replaced its Latin name with that of its people, abandoning Caesarodunum for Civitas Turonorum.[3] The urban fabric appears to have gradually retreated from the city's periphery towards the Loire front, which was less susceptible to flooding and where the most densely populated area was already concentrated.[3] This modification of the urban envelope seems to be accompanied by a profound change in construction methods: In the elevation of the walls, masonry is replaced by wood and earth, which does not contribute to the preservation of remains and may partly explain the lack of archaeological information from this period.[Gal 1]

The reasons for this evolution, which was observed in most Roman cities in Gaul during Late antiquity, are not precisely known but are undoubtedly multiple. The Crisis of the Third Century of the Roman Empire led to a decline in economic activity[4] and disrupted the functioning of the administration. Local factors may also have played a role; it is likely that floods of the Loire, like those experienced by Tours at that time, contributed to this modification of the urbanized area.[5] Furthermore, Tours faced the problems of insecurity related to barbarian incursions, which began in 250 and invaded the northern provinces of Gaul from the Germanic limes.[6]

Consequently, the inhabitants were compelled to confront the novel circumstances of a city vulnerable to assaults, even as its infrastructure was gradually disintegrating or, at the very least, undergoing a radical transformation.[Gal 1] In the second half of the 3rd century, the inhabitants began fortifying the amphitheater and surrounding it with a ditch.[Gal 2] They then considered constructing an enclosure with a tightened perimeter that would house the administrative authorities of the city, serve as a refuge for the inhabitants in case of attack,[7] and ultimately consecrate the birth of a new city from an urbanistic point of view.[Gal 3]

Dating of the enclosure[edit]

|

Evolution of dating hypotheses for the castrum.

|

After formulating numerous hypotheses regarding the dating of the castrum, archaeologists and historians have reached a consensus that the structure was constructed for several years, or even two or three decades, in the first half of the 4th century.[Pro 1] This dating is corroborated by the construction techniques typical of this period, including the use of opus mixtum,[14] the resumption of activity around 370 of the High Empire baths located in its northwestern corner after their redevelopment following the construction of the enclosure,[Gal 4] and finally by the abandonment of a defensive ditch previously built on the same site and revealed on part of the perimeter of the amphitheater.[Wd 1][Pro 2]

Subsequently, between 364 and 388, Tours benefited from an administrative reorganization of the Roman Empire and was elevated to the rank of capital of the Third Lyonnaise.[LP 1][Note 1] This period also saw the development of Christianity, notably under the episcopate of Martin.[3] In 1979, Henri Galinié and Bernard Randoin proposed that the construction of the castrum may have been the cause or consequence of Tours' accession to the rank of provincial capital of the Roman province.[AST 1] However, if the first proposition cannot be affirmed or denied, the second is no longer acceptable, as the chronology now establishes the precedence of the urban plan modification over the status change.

The wall would be reused, except its western flank, in several successive enclosures of Tours. These include the extension of the Arcis enclosure from the 12th century (listed in the General inventory of cultural heritage in 1991)[15] and the 14th-century enclosure (listed in the General Inventory of Cultural Heritage in 1991),[16] called Clouaison de Jean le Bon.[Note 2] This continued use is responsible for the survival of the GalloRoman enclosure of Tours, despite significant modifications and restoration efforts.

Architecture[edit]

The enclosure in the Late Empire[edit]

Origin of materials[edit]

The construction of the enclosure employed a systematic recycling of materials, using large blocks, small retouched stones, and tiles. These materials were sourced from monuments and buildings situated outside the enclosure perimeter. The large blocks, capitals, frieze blocks, and columns were likely obtained from public monuments within the city. The total mass of large blocks used in the wall construction is estimated at 50,000 tons.[HT 1] The small stones and terracotta (tubuli,[Note 3] brick, or tile fragments) are believed to have originated from private houses situated close to the rampart.[Aud 2] Several funerary elements (stelae) discovered in the foundations provide clear evidence of borrowings from the necropolises of Caesarodunum.[Aud 3] The contributions of reused materials may even have a more distant geographical origin. During his visit to Tours, Emperor Constantine requested that the stones from Amboise, a city located 25 km from Tours, be used for the construction of the rampart.[AST 2] This massive reuse of old building materials is not an isolated case and does not imply an accidental abandonment of old buildings. Rather, it was common in the Roman Empire to program the recycling of old materials in new constructions.[17]

Foundations[edit]

The precise structure of the monument remains unknown, as no excavation has yet reached its base.[S3 1] The structure is composed of several courses of large recycled limestone blocks, including hard chalk or tuffeau stone, raw or sculpted blocks, capitals, column drums cut in half, and other materials. These blocks are stacked with tight joints in a trench at least 3 meters deep, with a width that far exceeds that of the wall in elevation. The upper level does not exceed that of the ancient ground, around 48.50 meters NGF. The ancient ground, at approximately 48.50 meters NGF, appears to be relatively consistent throughout the entire perimeter of the enclosure.[S3 1] At least six courses of large blocks have been identified on site 3, and it is not excluded that the base of the foundations, at least in this sector along the Loire, is established on wooden piles.[S3 2] While the exterior side of the foundations is aligned with the alignment of the wall of the enclosure, the interior side extends approximately 1.50 meters in the northwest corner, the only point of the enclosure where they have been accessible.[S3 3]

Curtain wall[edit]

The excavations conducted on Site 3 have enabled the identification of the internal structure of the wall. From the foundations, the curtain wall exhibits two distinct structural configurations.[S3 4] In the subsequent description, the numerals and letters in parentheses correspond to the markers illustrated in Figure I.

The initial course above the foundations comprises substantial blocks whose structural configuration is analogous to that of the foundations, albeit with a chamfered outer row (on average 0.30 meters). This initial course is surmounted by a series of rows of large blocks across the entire width of the wall (5), collectively forming the base (S) of the curtain wall.

Above the base, the elevation (E) is composed of two small walls constructed of rubble masonry with pink mortar (2) interspersed at variable intervals with courses of bricks across their entire width (3). Once completed, the outer face of the wall will be faced with small rectangular limestone stones cemented with pink mortar (1). These two small walls, with a width of 0.40 to 0.60 meters, form two formwork panels whose gap is filled with rubble composed of irregularly shaped stones, assembled with white mortar (4). The two small walls, with a width of 0.40 to 0.60 meters, are formed by rectangular limestone stones cemented with pink mortar (1). These walls serve as formwork panels, with the gap between them filled with rubble composed of irregularly shaped stones, assembled with white mortar (4). Upon completion of the curtain wall, only the outer facing in opus mixtum, a dominant feature in Gallo-Roman constructions of the Late Empire, is visible.[7] Due to its continued use until the early 17th century, the castrum has undergone numerous repairs, except for its quickly leveled western face. The opus mixtum, replaced by other types of masonry, is now only visible in a few places. The holes observed at regular intervals are those created by scaffolding and not formwork key positions.[Wd 2]

The width of the wall is relatively consistent, ranging from 4.20 to 4.90 meters, including the facings. It appears to have been constructed in a series of vertical sections, including a tower and the section of curtain wall leading to the next tower. At an undetermined date, the curtain wall was partially leveled over its entire perimeter. However, by examining the level of the tower windows that accompany it and the level of its leveling, and comparing these data with the enclosures of other cities, it is possible to attribute to the wall an initial height of approximately 8.10 meters, excluding the crenellation. This crenellation, which is likely to have existed, has left no remains; its height is estimated at 1.80 meters above the walkway.[S3 5] The mode of access to the walkway is not known. However, a structure still present in the southeastern corner of the enclosure and included in the Museum of Fine Arts could be interpreted as a staircase built into the thickness of the wall and leading to the southwestern corner tower.[S3 6]

The towers[edit]

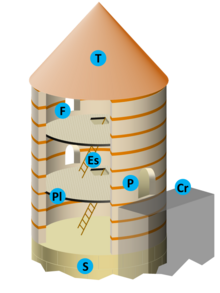

The structural composition of the towers is analogous to that of the wall. The following description employs the letters in parentheses to correspond with the markers illustrated in Figure II.

The foundation (S) is composed of substantial reused blocks. The upper levels feature a combination of opus sectile and opus mixtum masonry. The interior is hollow, comprising three floors separated by intermediate floors (Pl). Access to the tower was likely at the intermediate floor level through a door (P) opening onto the rampart walkway (Cr) at the top of the curtain wall. The other floors were accessed via ladders or internal staircases (Es). The lower floor of the tower was likely windowless, while the other floors were equipped with windows (F).[Aud 4] Previous reconstructions imagined a solid structure up to the height of the current first floor.[Wd 3]

The towers are almost all circular, with an external diameter of 9 meters. They extend beyond the enclosure to allow for unobstructed circulation on the walkway. The corner towers have their diameter increased to 11 meters.[Gal 5]

The initial comprehensive investigation of the enclosure, conducted in the early 1980s, revealed the existence of 25 towers along the wall on its four sides, in addition to those along the wall of the amphitheater bastion.[Wd 3] This figure has been revised downward. It can be reasonably assumed that the amphitheater did not receive additional fortification during its integration into the castrum. Its high wall and massive structure did not justify such an addition. Furthermore, the traces of towers discovered by Jason Wood are more likely remnants of towers built in the Middle Ages during repairs made to the amphitheater.[Lef 1] The northern part of the enclosure, bordered by the Loire, could also be devoid of watchtowers. Furthermore, the number and location of towers on the eastern and western sides of the castrum have been re-evaluated. The available studies conducted in 2014 indicate that the enclosure likely had only 12 circular towers at the time of its construction, including four corner towers, plus four polygonal towers flanking the western and eastern gates. This arrangement is similar to that found in Le Mans and Die. The recent discovery of one of these polygonal towers, previously thought to be circular, has prompted a re-examination of the location of the gates.[Gal 5]

Considering the number of floors that must have existed, the towers are estimated to have reached a height of 16 meters, which is twice that of the curtain wall. Concerning the roofing of the structures, the conical roof (T) of the surviving corner tower, which underwent significant restoration in the 19th century, represents one potential configuration. An alternative hypothesis is that the roof was single-sloped.[S3 1]

Access to the enclosure[edit]

Two posterns have been identified through the examination of their remains. The so-called southeast postern is situated to the east of the amphitheater bastion. Measuring 3.20 meters in width externally and 3.85 meters in height, its floor paving is marked with two ruts in which the wheels of passing carts fit.[Note 6] It was modified on several occasions during the Middle Ages. The road exiting the city through this postern led southeast,[Aud 1] but within the enclosure, there is no evidence to suggest whether it was connected to the street network.[Lef 2] The northwest postern, known as Turnus' Tomb, is located in the northwest corner of the enclosure.[Pro 3] Its former lintel, made of a decorated block,[Note 7] was dismantled in the 19th century for preservation. This structure was probably erected during the construction of the enclosure, as it is only 2.30 meters in height. Over the centuries, it has undergone numerous modifications. It has frequently been walled up and then reopened, and it does not appear to be connected to a hypothetical street network inside the castrum. Instead, it seems to have been reserved for the exclusive service of the successive buildings in the northwest corner.[S3 5]

The existence of two gates is certain, although no remains have been verified as of 2014. The northern gate is a recent discovery. In 2000, archaeologists found that the castrum was served by a wooden bridge crossing the Loire at the level of the Île Aucard (many piles in place were found in the riverbed during low water). This bridge ended in the middle of the northern wall, in alignment with the main axis of the amphitheater.[18] This discovery, in conjunction with the interpretation of geophysical survey results by apparent resistivity[Note 8] in the same area, suggests the potential existence of a gate at this point in the wall.[19] It appears that this gate was already depicted around 1780 by the actor and illustrator Pierre Beaumesnil, who was commissioned by the Academy of Inscriptions and Letters to reproduce ancient monuments in France, including those in Tours. One of his drawings shows the upper arch of a walled-up and almost completely buried gate, located precisely where the northern gate of the Gallo-Roman enclosure might be.[Gal 6] The entire structure, comprising the bridge, the gate providing access to the Cité, and the fortified castrum setup, appears to function as a lock, allowing complete control over the river crossing.[Gal 7] No other bridge seems to exist on the Loire in the Late Empire, several kilometers upstream or downstream.[Aud 5] Contrary to previous assumptions, the vomitoria were not walled up during the integration of the amphitheater into the fortified enclosure. Instead, the three western, southern, and eastern vomitoria, which were kept outside the walled perimeter, were converted into monumental access gates to the enclosure. Moreover, the ancient road passing through the amphitheater's small axis was preserved outside the castrum after its construction.[Gal 8]

The existence of two main gates on the eastern and western sides is almost certain, and they probably faced each other.[Aud 6] However, no confirmed trace of these gates has been found. In the History of the Franks (Book X, 31), Gregory of Tours makes the following reference to them:

Now, while he was entering through one gate, Armentius, who had died, was being carried out through another.[20]

In this account, Gregory describes the return of Bishop Brice to Tours after seven years of exile in Rome and his entry into the city through the eastern gate (heading towards Rome) while his replacement has just died and his body leaves the city through the western gate to be buried in Saint Martin's basilica. The location of these gates on the lateral sides of the castrum is still a matter of debate. Until the 1980s, it was assumed that the gates were relocated to the north from the median of the lateral walls (Hypothesis A in Figure III), thus continuing the decumanus of the High Empire city that would have crossed the castrum.[Aud 6][Wd 4] However, the discovery of the polygonal tower mentioned previously challenges this proposal. This tower, a model known for flanking the gates of enclosures in the Late Empire, is located further south on the eastern face. Another tower facing the gate on the same wall likely exists, as well as a symmetrical group of two towers on the western flank.[Gal 5] The second hypothesis proposes that the road linking the towers, which passes further south in the castrum, would divide the enclosed space into two roughly equal northern and southern parts. This indicates a complete restructuring of the street network in this part of the city.[Gal 3]

Evolution during the Early Middle Ages[edit]

Following the construction of the Arcis enclosure, likely in the 12th century,[21] it is plausible that the castrum no longer exists as an independent architectural entity but rather as a component of a larger complex. Modifications made to it from the 12th century onwards, within the context of the enlargement of the enclosures of Tours, will not be addressed here.

In the mid-9th century, France was subjected to a series of raids by the Normans. The first attack occurred in the Loire Valley and particularly in Tours on 8 November 853. The last attack took place on 30 June 903. According to tradition, the attackers of the Cité were driven away by the sight of Martin's casket, displayed atop the ramparts.[22] In response to this threat to his kingdom, Charles the Bald, as recorded in the annals of Saint-Bertin, requested in 869 that the walls of several cities in northern France, including Tours, be repaired. This request was probably made in the context of a rapid repair program for the enclosure of the castrum in Tours.[Lef 3]

The restoration of the enclosure[edit]

An excavation conducted at the base of the amphitheater between 1978 and 1982, behind the Departmental Archives building,[Gal 9] revealed that the facade wall of the amphitheater, likely in a state of disrepair, had partially collapsed between the 5th and 7th centuries. The resulting breach was only temporarily repaired, possibly during the repair campaigns ordered by Charles the Bald. The blocks, some of which were sculpted, were likely derived from an ancient structure that had survived until that point within the castrum. This structure was probably a basilica.[Gal 10] These blocks were used for this purpose. At approximately the same time and in the same area, at least two towers were constructed against the facade of the amphitheater. The remains of one of these towers are still visible.[Lef 1] During the study of the castrum conducted in 1981, these towers were mistakenly described as ancient and contemporary with the construction of the enclosure. It can be reasonably assumed that the repairs to the enclosure were completed in 877, as this was the date by which the relics of Saint Martin had been brought back to safety inside the castrum.[Gal 11]

This site is the only one where repairs to the enclosure are confirmed and dated to the Early Middle Ages as of 2014. In other locations on the perimeter of the enclosure, they have not been identified, either because no study has been conducted or because, as in Site 3, the leveling of the wall has removed its elevation along with any possible traces of restoration.[S3 4]

Digging a defensive ditch[edit]

The repair of the amphitheater facade was accompanied by the digging of a defensive ditch, the location of which was identified only at the site of the Departmental Archives. However, it may have surrounded the castrum, except to the north, where it was unnecessary due to the presence of the Loire. The ditch was filled with stagnant water (thus probably without direct or permanent communication with the river) and dug about 15 meters from the outer face of the amphitheater wall. Its dimensions are poorly known, as its banks have been leveled. It was gradually filled in to disappear in the 11th century.[Gal 11]

The Cité: A new plan for a new town[edit]

Location and layout[edit]

The enclosure's generally good state of preservation has allowed for the layout to be well known in broad terms. This is notably due to the works of General de Courtigis, who was tasked in 1853 with inventorying all Gallo-Roman remains in Tours for the Archaeological Society of Touraine.

The castrum enclosure was established in the northeastern part of the High Empire city, integrating the amphitheater into its structure. This integration benefits from the favorable topographical features that had dictated the choice of the amphitheater's location. The amphitheater is situated on an alluvial eminence, which culminates a few meters above the general level of the ancient city. This elevation limits the effects of Loire floods.[Gal 12]

The southern face of the castrum is rectilinear, except for the southern half-ellipse of the amphitheater, which forms a bastion. At this level, the curtain wall abuts the amphitheater facade, with the north-south axis passing precisely through the median of the southern wall of the enclosure. The layout and organization of the enclosure appear to have been designed based on the presence of the amphitheater and are structured around it.[Gal 3] Late antique enclosures that integrated an amphitheater into their fortification system are relatively common in Gaul. Examples include Trier and Périgueux.[23] However, no situation has yet been encountered where the integration is as complete and where the plan of the newly walled city is so conditioned by the presence of the monument.[Gal 3]

The east and west walls converge at an oblique angle beyond the right angle, extending from Lavoisier Street to the east and the Petit-Cupidon and Port-Feu-Hugon streets to the west. The southwest angle of the enclosure may have been opened to deviate from the western part of the wall and thus save part of the High Empire thermal complex, located northwest of the enclosure, which was threatened by the construction of the castrum.[S3 3]

To the north, the enclosure, now separated from the Loire by André-Malraux quay, follows the ancient riverbank as closely as possible. This explains why it is not perfectly rectilinear in its eastern part.[S3 3] It serves as the base for the Governor's residence along its entire length and the Tours castle (north gable wall of the Mars Pavilion) for modern buildings.

The layout of the enclosure, as proposed in 2014, is not significantly different from that presented in the 1855 plan, except for the addition of access points and towers. The resulting configuration of the castrum encompasses an area of 9 hectares, with a perimeter of 1,245 meters.[Gal 8]

The geometric layout of the enclosure, which is an almost rectangular trapezoid, is barely disturbed by topographical constraints. Furthermore, the presence of the amphitheater that structures the castrum around it suggests that the enclosure was carefully planned. This is evidenced by the fact that it is "closer to that which presided over the establishment of legionary camps than to that of the majority of urban enclosures in Gaul of the same period."[S3 3] Furthermore, this evidence supports the argument that the construction was not hastily undertaken, contrary to the hypotheses that have been proposed until recently, which viewed the Late Empire enclosures as hastily constructed in response to persistent insecurity.[17]

A proposed reconstruction of the castrum (3D animation), posted on the website of the National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP), depicts the general architectural layout of the enclosure and its structural integration with the amphitheater.[24]

Life in the Cité[edit]

Similarly, the examination of the modes of occupation of the Cité, the area circumscribed by the castrum walls, will be limited to the ancient and early medieval periods, for the same reasons that the study of the enclosure's repairs was limited to those periods. As of 2014, the available knowledge in this area remains fragmentary, based mainly on a few rare written sources (historical texts, charters, deeds of donation, or land exchanges), the results of excavations on site 3, and an archaeological survey at Paul-Louis-Courier High School. Additionally, the area northeast of the cathedral apse (under the responsibility of Anne-Marie Jouquand, INRAP, as part of a high school expansion project)[Lef 4] and Bastien Lefebvre's work on the evolution of buildings within the old amphitheater's footprint were investigated.[25]

The disparate and fragmentary nature of the available evidence precludes the possibility of constructing a comprehensive picture of life in the Cité at any given moment in Late Antiquity or the Early Middle Ages.[AST 1] Nevertheless, it is clear that religious authority, in the form of the bishop, was consistently present there, even if, as was the case with Martin, the bishop did not always reside there.[26] It is possible that representatives of administrative or political authority, at a level yet to be defined, resided there before the counts of Anjou in the 11th century.[S3 7]

The road network[edit]

It is uncertain whether roads were constructed within the enclosure at the time of its construction. However, a north-south road probably connected the north vomitorium of the amphitheater to the gate in the middle of the north curtain wall of the enclosure. Similarly, it is permissible to imagine a circulation axis connecting the eastern and western gates of the castrum, assuming these exits existed and their locations were fixed. These hypotheses suggest that the Cité would have been crisscrossed by two roads intersecting at right angles in its center, dividing its space into four roughly equal quadrants.[Gal 3] However, the two confirmed posterns do not appear to connect to this sketch of a road network.[Lef 2][S3 5]

Religious buildings[edit]

The works of Gregory of Tours[Gal 13] and early medieval charters have permitted the approximate location of religious buildings within the enclosure to be determined, although the buildings themselves have not been archaeologically identified.

The first cathedral of Tours is traditionally attributed to Lidorius, the first bishop of the city between 337 and 370. It seems likely that this ecclesia prima was located at the site of the current cathedral,[LP 2] with its entrance facing east and situated opposite the wall. The presence of a baptistery in the vicinity, possibly to the north of the cathedral, has not been confirmed but seems a reasonable assumption.[LP 3] Eustochius, bishop of Tours from 442 to 458 or 459, is believed to have constructed a church dedicated to Saints Gervais and Protais, located south of the cathedral.[LP 4] Ommatius completed the cathedral group between 552 and 556 with a basilica dedicated to Saint Mary and Saint John the Baptist. This building was only completed between 529 and 547 and could be located north of the cathedral.[LP 3] The location of the bishop's residence is not defined.[Lef 5] The disadvantage of physically distancing the bishop and his seat from the predominantly extramural Christian population was offset by the official status granted to the bishop since Constantine's reforms in 324, which required the main religious buildings to be located within the Cité.[Aud 7]

A diploma dated 919 attests to the existence, near the northeast corner of the castrum, in the second half of the 9th century, of a church (potentially located at the site of the current Saint-Libert Chapel) and a postern in the wall. However, these two structures have not been archaeologically confirmed as of 2014.[27]

In the northeast corner of the enclosure, around 875, a structure that would later become the Basilica of Saint-Martin-de-la-Bazoche provided shelter for the relics of Saint Martin once the Cité walls were repaired.[28]

Civil buildings[edit]

The northwestern part of the castrum has been the subject of extensive study, and the history of the area, at least in terms of its architectural remains, appears to be relatively well-documented. The High Empire public baths, which were in use before the construction of the enclosure, ceased to function during the wall's erection. The partially amputated and reorganized structures resumed their activity for a few decades at the end of the 4th century before being partly converted into housing. The rest of the bath buildings were replaced by built structures where masonry partially gave way to earth. Subsequently, during a period with no clear evidence of occupation, the 7th century, there was, towards the mid-8th century, an enclosure with an ill-defined function indicating a partition of space within the Cité. Construction resumed at the beginning of the ninth century.[S3 8]

In the center of the Cité, preliminary excavations conducted before the construction activities at Paul-Louis Courier High School revealed evidence of domestic habitation, including a silo and a cesspit, which date back to the 9th century.[Lef 6]

The inhabitants of the Cité[edit]

The "archives of the soil" offer only limited insight into the number and nature of the inhabitants of the Cité. A few subtle clues provide only tentative indications about the population of the castrum.

Site 3 appears to have been reserved throughout Late Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages for inhabitants belonging to some form of social or political elite, whose precise nature is yet to be defined. However, their status seems evident. This hypothesis is based on the continuity of the public status of the buildings that preceded (High Empire baths) and followed (the 11th-century count's residence) during this period.[S3 7]

In the Late Empire or early Early Middle Ages, populations of foreign origin (perhaps auxiliary troops) may have resided in the castrum for an extended period. This is indicated by the presence of fibulae in the Cité or its immediate vicinity,[Gal 14] as well as hand-shaped ceramics typical of the late 4th and 5th centuries.[Note 9] These artifacts are believed to have been locally produced and may be attributed to populations of foreign origin who were living in a degraded economic environment.[Gal 15] Another potential clue is the discovery of a significant number of horse bones in a 3rd-century ditch that was filled in the following century. This observation reflects the dietary habits of Germanic populations during that era.[Gal 16]

Bastien Lefebvre's work does not contribute to our understanding of the evolution of the amphitheater during the Early Middle Ages. It does not provide answers to questions regarding the modes of occupation of the amphitheater's footprint and the population of this neighborhood.[Lef 6]

However, a schematic overview of the period from the 4th century to the 10th century reveals that the northern half of the Cité was occupied by a secular population, with representatives of administrative authority at the forefront. In contrast, the southern part appears to have been devoted to religious figures, centered around the bishop.[AST 3]

The environment of the Late Empire Cité[edit]

If it is agreed that the castrum housed the administrative and religious authorities of the city, it remains to be defined what city this was. Until the 1980s, some archaeologists and historians believed that all traces of habitation had practically disappeared outside the walls. This was due to the fear that these buildings could be used as forward posts by potential assailants,[Wd 5] and that the open antique city had given way to ruins and agriculture.[HT 2] This working hypothesis was not unique to Tours but was formulated for many cities in Gaul at the same time. It was mainly based on the presence in archaeological strata of a poorly understood feature, the dark earth, attributed to the abandonment of former urbanized areas.[29] Despite the need for further advances to better understand this black earth, it is now accepted, even by those who envisioned a return to nature in ancient cities, that it reflects a persistent human presence but with totally renewed lifestyles.[30]

The establishment of Christianity in Tours constituted a pivotal moment in the city's history, influencing the urban landscape beyond the walls of the Cité.[HT 3][Gal 17] In the 4th century, Lidorius initiated the construction of a basilica approximately 1 km west of the Cité.[LP 5] Additionally, in 397, Martin was laid to rest in a Late Empire necropolis situated a few hundred meters southeast of this basilica.[Gal 18] His tomb was accompanied in the 5th century by a basilica in his honor, which preceded the urban development of this area in the Middle Ages. Some rare civil buildings are attested in the Late Empire between these basilicas and the Cité, such as the site of Saint-Pierre-le-Puellier,[Aud 8] and a dwelling closer to the current city center, equipped with a bathhouse in the 3rd century.[Gal 17] Outside of these few archaeologically verified markers, there is no evidence to suggest otherwise. However, merchants and artisans were probably established in the vicinity of the castrum to meet the needs of the intra-muros population.[Aud 9]

The lack of knowledge of the history of Antiquity and the Early Middle Ages in Tours can be largely attributed to two factors directly related to the constraints of urban archaeology. The thickness of the archaeological strata reaches 8.5 meters in the most ancient and densely populated areas, namely along the Loire.[Gal 19] It is relatively straightforward to comprehend the practical difficulty of conducting excavations or even surveys at such depth on generally quite small surfaces. The excavated area represents only a small fraction of the ancient urbanized space, ranging from 0.6 to 1.5% depending on the historical period under consideration. Given this low representativeness, it is inadvisable to extrapolate the obtained results.[Gal 20]

The appearance of this provincial Roman capital in 2014 remains largely unknown. It is situated between a castrum of a few hectares that could only house a limited number of inhabitants[HT 4] and a suburbium whose occupation modes are still in question.[Gal 17]

Studies and remains[edit]

Main studies on the castrum[edit]

In 1784, actor and draughtsman Pierre Beaumesnil published, at the behest of the Academy of Inscriptions and Letters, the collection Antiquités et Monuments de la Touraine (1784). This document reproduces several drawings of the 4th-century wall, including the north face, where a gate, subsequently lost but rediscovered in the early 2000s through geophysical prospecting methods, is visible.[Gal 6]

The Archaeological Society of Touraine (SAT), established in 1840 in a period of considerable interest in archaeology[31][Note 10] at the national level, played a pivotal role in mapping the enclosure. At the beginning of the 19th century, the prominence of the amphitheater was considered a medieval addition.[Wd 6] An 1841 plan of the castrum showed a strictly rectilinear south face, which ignored the amphitheater bastion. However, members of the commission, created in 1853 to inventory the ancient remains of Tours, led by General de Courtigis,[Note 11] discovered that in the cathedral district cellars, they were not exploring the remains of monumental baths[32] as they had previously thought, but those of an amphitheater.[Gal 21] As a result of these discoveries, the enclosure plan could be corrected as early as 1855.

In 1938, Baron Henry Auvray published the results of his observations on the remains of ancient Touraine in the SAT bulletins under the title La Touraine gallo-romaine. The Late Empire enclosure was the subject of considerable attention, with Auvray collating previous discoveries associated with it and supplementing them with his observations in the form of a "promenade" along the rampart.[33]

From 1974 to 1978, Site 3, i.e., the northwest corner of the 4th-century enclosure, was subject to five excavation campaigns of approximately ten weeks each. The High Empire baths and their evolution in the Late Empire, the initial structures of the Early Middle Ages, and subsequently, the 11th-century Tours castle, underwent continuous modification until their destruction at the turn of the 19th century. These modifications were studied in detail at Site 3. It is also on Site 3 that knowledge about the structure of the Late Empire enclosure is most precise, as even the foundations were (partially) accessible. Although the results of this long excavation have been partially published on several occasions, the final report was not published until June 2014.[34] The delay between excavation and publication was used to perfect the analysis of the collected data thanks to computer tools, nonexistent forty years earlier.[S3 9]

In 1978, a project to expand the Departmental Archives building presented the opportunity to conduct excavations at the foot of the castrum wall, in the southeast curvilinear part of the amphitheater. The results of these excavations, conducted from 1978 to 1982, led to a rewriting of the history of the amphitheater's integration into the fortified enclosure and its evolution during the Early Middle Ages. This subject was published in the journal Tours antique et médiéval.[35][36]

In 1980, archaeologist Jason Wood conducted a comprehensive investigation of the castrum. Published in 1983,[37] this study remains the sole comprehensive examination of the Late Empire enclosure to date, although subsequent works have challenged some of its conclusions.

In 1983, Luce Pietri published a doctoral thesis entitled La ville de Tours du IVe au VIe siècle. Naissance d'une cité chrétienne. The thesis examines the role of Christianization and its actors (including Martin) in the topographical and historical genesis of the city. It is based on existing archaeological data and historical text analysis. Among other things, the thesis proposes an organizational scheme for the episcopal group within the Cité.[38]

In 2003, archaeologist Jacques Seigne undertook a reexamination of all the data from previous archaeological studies concerning the Late Empire's enclosure. He supplemented this with more recent work (2003: discovery of ancient bridges, 2005: new perspective on the history of the amphitheater) to update the knowledge about the castrum. His work has been published, with several chapters in Tours Antique et Médiéval dedicated to it.[3]

In 2008, in his doctoral thesis in archaeology, Bastien Lefebvre examined the evolution of the canonical district of Tours, which encompasses a portion of the city built on the ruins of the amphitheater. Over the centuries, the district has undergone significant changes. Although the castrum was not the primary focus of his research, Lefebvre described the repairs made to the amphitheater integrated into the ancient enclosure in the 9th century and sought to clarify the land use modalities during the Early Middle Ages in the part of the city within the amphitheater's footprint.[1]

Remnants of the enclosure[edit]

The Late Empire's enclosure of Tours has been partially designated as a historic monument since 1927, with the designation of a registered building.[1] The enclosure's significant remains are still visible in the open air[Note 12] (the numbers in parentheses refer to the captions of the photographs below or the markers locating these remains in Figure IV).

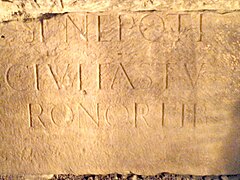

The foundations can be accessed in the cellars of the Musée des Beaux-Arts (former archbishopric), place François-Sicard, as well as in neighboring cellars. Among the reused elements, one can see sculpted blocks (7), sawn columns (8), two engraved blocks celebrating "the free city of the Turoni": CIVITAS TVRONORVM LIBERA (9 and 10), and a square capital (11).

Two posterns remain visible, one in the southeast in the Jardin des Vikings, with intact flooring (1), and one in the northwest on Quai André-Malraux (2).

Several towers survive in the city, including the corner tower "de l’Archevêché" in the southwest, within a dependency of the Musée des Beaux-Arts, place François-Sicard. This tower was heavily restored in the early 20th century, but its original height is likely to have been respected (3). The tower "du Petit-Cupidon" in the southeast on Rue du Petit-Cupidon,[39] though named for a 17th-century tradition placing it at the site of a Roman temple dedicated to Cupid,[AST 4] is truncated at the height of the curtain wall. It was provided with a balustrade at an undetermined time (Wd 3).[Wd 3] In addition, the remains of three other towers can be discerned: the curved base of the first can be observed in the masonry elevation of the southern tower of the cathedral, while the bases of the other two are located at the entrance to the Psalette cloister and the northwest corner of the castrum (site 3).

Portions of the rampart are visible at the entrance to Rue Fleury, on the south side, where the internal structure of the wall is revealed. Additionally, sections are visible adjacent to the north tower of Saint-Gatien Cathedral on the west face. Further sections are found at the intersection of Rue des Maures and Quai André-Malraux, as well as near Chapelle Saint-Libert on Quai André-Malraux for the northern part.

A significant portion of the curtain wall remains intact. The longest section is located in "Jardin des Vikings" on Rue des Ursulines, extending from the amphitheater to the tower of Petit-Cupidon. This stretch includes a breach attributed to the Normans during their 903 raid attempt to capture Tours[39] (4). The wall is preserved nearly to its full height, from the reused large stone foundations (5) up to the top of the curtain wall. However, the original opus mixtum is only visible in places due to successive renovations. Behind buildings on Rue du Petit-Cupidon and Rue du Port Feu-Hugon, interior courtyards bounded on the west by the wall allow views of curtain sections where small stonework is well-preserved. On the northern side, the foundations of the north wall of Chapelle Saint-Libert (12) and the Logis des Gouverneurs on Quai André-Malraux (6) are formed by the wall itself. Further west, another curtain section forming the base of Tours castle links to the northwest postern and corner tower.

- Aerial remains of the enclosure of the castrum of Tours

-

Photo 1: South-east postern.

-

Photo 2: North-western postern.

-

Photo 3: Archbishop's Tower.

-

Photo 4: Normand breach.

-

Photo 5: Large boulder base.

-

Photo 6: Courtine.

- Subterranean remains of the enclosure of the castrum of Tours

-

Photo 7: Sculpted fill blocks.

-

Photo 8: Replacement columns.

-

Photo 9: Engraved block from the free city of Turons.[Note 13]

-

Photo 10: Engraved block from the free city of Turons.[Note 14]

-

Photo 11: Replacement capital.

See also[edit]

Notes[edit]

- ^ The IIIe Lyonnaise included Touraine, Anjou, Maine, and Brittany.

- ^ By letters patent dated March 1356, King John II "the Good" authorized the inhabitants of Tours to continue the construction of a new enclosure intended to unite the various urban nuclei that would constitute the late medieval city (Chevalier 1985, pp. 107–108).

- ^ Tubuli were terracotta pipes that channel hot air or smoke in ancient baths.

- ^ This drawing is as faithful a transcription as possible of the description of the curtain wall based on available archaeological data.

- ^ This drawing is as faithful a transcription as possible of the description of the towers of the enclosure based on available archaeological data, except for the details of interior fittings, masonry, window placements, and roof nature, which are only suggestions.

- ^ These grooves could be traces of stone wear from wheel passage or, conversely, intentionally cut into slabs to guide wheels.

- ^ This decorated lintel has long been interpreted in popular tradition as the sarcophagus of Turnus, a Trojan considered the founder of Tours; Turnus is a legendary figure and the lintel is a solid block (Audin 2002, p. 9).

- ^ Resistivity surveying uses variations in soil electrical resistance to highlight heterogeneities.

- ^ According to Cécile Bébien, hand-modelled ceramics were abandoned during the first three centuries AD in favor of turned ceramics. Its reappearance is considered a "chronological marker" of the 4th or early 5th century (Galinié 2007, p. 222: L'usage de la céramique modelée).

- ^ Following Bonaparte's Egyptian campaign between 1798 and 1801, interest in Egyptian, but also Roman, antiquities had led to the creation of numerous learned societies in the field of archaeology.

- ^ General de Courtigis was then in command of the division quartered in a barracks near the Tours castle.

- ^ Other known ancient remains of Tours (amphitheater, temple, domus, baths, traffic routes) are buried in the ground or in private cellars.

- ^ Text completed with inscription: CIVITAS TV(RONORVM) LIBERA.

- ^ Text completed with inscription: (...)SI NEPOTI CIVITAS TVRONOR(VM) LIB(ERA).

References[edit]

- Tours à l'époque gallo-romaine (2002)

- ^ a b Audin 2002, pp. 96–97: Le rempart du castrum

- ^ Audin 2002, p. 92: Le rempart du castrum

- ^ Audin 2002, p. 71: Deux nécropoles aux portes de la ville

- ^ Audin 2002, pp. 94–95: Le rempart du castrum

- ^ Audin 2002, p. 89: Le rempart du castrum

- ^ a b Audin 2002, pp. 95–96: Le rempart du castrum

- ^ Audin 2002, pp. 103–104: Tours, cité chrétienne

- ^ Audin 2002, pp. 83 & 85: Caesarodunum au Bas-Empire

- ^ Audin 2002, p. 99: Le rempart du castrum

- Histoire de Tours (1985)

- ^ Chevalier 1985, pp. 14–15: Genèse du paysage urbain

- ^ Chevalier 1985, p. 20: IVe-VIIIe siècle, un centre politique et spirituel sans vie urbaine

- ^ Chevalier 1985, pp. 49–50: La cité chrétienne

- ^ Chevalier 1985, p. 19: IVe-VIIIe siècle, un centre politique et spirituel sans vie urbaine

- Les archives du sol à Tours: survie et avenir de l’archéologie de la ville (1979)

- ^ a b Galinié & Randoin 1979, p. 22: Tours au Bas-Empire

- ^ Galinié & Randoin 1979, p. 20: Tours au Bas-Empire

- ^ Galinié & Randoin 1979, p. 32: Tours du IXe au XIe siècle

- ^ Galinié & Randoin 1979, p. 18: Tours des origines au IIIe siècle

- Tours antique et médiéval. Lieux de vie, temps de le ville. 40 ans d'archéologie urbaine (2007)

- ^ a b Galinié 2007, pp. 17–18: Préambule historique et archéologique

- ^ Galinié 2007, pp. 238–246: Les trois temps de l'amphithéâtre antique

- ^ a b c d e Galinié 2007, pp. 359–361: La fortification de la ville au ive siècle : un nouveau plan d'urbanisme

- ^ a b Galinié 2007, p. 255: La fortification de la ville au Bas-Empire, de l'amphithéâtre forteresse au castrum

- ^ a b c Galinié 2007, pp. 251–253: La fortification de la ville au Bas-Empire, de l'amphithéâtre forteresse au castrum

- ^ a b Galinié 2007, pp. 250–251: Les antiquités de Tours au xviiie siècle d'après Beaumesnil

- ^ Galinié 2007, p. 238: Les ponts antiques sur la Loire

- ^ a b Galinié 2007, p. 249: La fortification de la ville au Bas-Empire, de l'amphithéâtre forteresse au castrum

- ^ Galinié 2007, pp. 83–90: La fouille du site des « Archives » rue des Ursulines

- ^ Galinié 2007, pp. 330–332: Des monuments révélés

- ^ a b Galinié 2007, p. 89: La fouille du site des « Archives » rue des Ursulines

- ^ Galinié 2007, p. 241: Une montille à l'origine de l'amphithéâtre

- ^ Galinié 2007, pp. 285–286: Les édifices chrétiens d'après Grégoire de Tours

- ^ Galinié 2007, p. 222: Les quelques insignes militaires

- ^ Galinié 2007, p. 222: L'usage de la céramique modelée

- ^ Galinié 2007, p. 221: La consommation de cheval dans la Cité

- ^ a b c Galinié 2007, pp. 355–356: La ville close, la Cité ; l'espace urbain vers 400

- ^ Galinié 2007, pp. 373–374: Les vivants et leurs morts du premier au douzième siècle : de l'éloignement à l'insertion

- ^ Galinié 2007, pp. 43–44: L'évaluation du potentiel archéologique

- ^ Galinié 2007, pp. 41–42: La connaissance archéologique de la ville

- ^ Galinié 2007, p. 239: La découverte de l'amphithéâtre au 19e siècle

- Des Thermes de l'Est de Caesarodunum au Tours castle: le site 3 (2014)

- ^ a b c Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, p. 45: L'architecture de l'enceinte urbaine du ive siècle

- ^ Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, p. 116: Le mur de l'enceinte urbaine du ive siècle. Étude architecturale

- ^ a b c d Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, p. 44: L'architecture de l'enceinte urbaine du ive siècle

- ^ a b Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, pp. 115–116: Le mur de l'enceinte urbaine du ive siècle. Étude architecturale

- ^ a b c Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, p. 117: Le mur de l'enceinte urbaine du ive siècle. Étude architecturale

- ^ Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, pp. 47–48: L'architecture de l'enceinte urbaine du ive siècle

- ^ a b Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, pp. 55–57: La présence de l'élite, bâtiments, enclos, objets, vers 450-vers 1050

- ^ Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, pp. 47–53: La présence de l'élite, bâtiments, enclos, objets, vers 450-vers 1050

- ^ Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014, p. 10: Préface

- La formation d’un tissu urbain dans la Cité de Tours: du site de l’amphithéâtre antique au quartier canonial (5th–18th s.) (2008)

- ^ a b Lefebvre 2008, pp. 206–207: La restauration du rempart au ixe siècle

- ^ a b Lefebvre 2008, p. 241: La trame viaire

- ^ Lefebvre 2008, p. 206: La restauration du rempart au ixe siècle

- ^ Lefebvre 2008, p. 88: Le site au début du haut Moyen ge

- ^ Lefebvre 2008, p. 75: L'espace urbain du Haut Moyen ge

- ^ a b Lefebvre 2008, p. 89: Le site au milieu du ixe siècle

- La ville de Tours du 4th au 6th century. Naissance d'une cité chrétienne (1983)

- ^ Pietri 1983, pp. 12–14: La civitas Turonorum au iiie et au ive siècle

- ^ Pietri 1983, pp. 354–355: L'ecclesia

- ^ a b Pietri 1983, p. 362: L'ecclesia sanctae Mariae Virginis ac sancii Johannis Baptistae

- ^ Pietri 1983, p. 356: L'ecclesia sanctorum Gervasii et Protasii

- ^ Pietri 1983, pp. 368–372:La basilica Sancti Litorii

- Carte archéologique de la Gaule – l'Indre-et Loire-37 (1988)

- ^ Provost 1988, pp. 96–97: L'enceinte gallo-romaine

- ^ Provost 1988, p. 96: L'enceinte gallo-romaine

- ^ Provost 1988, p. 95: L'enceinte gallo-romaine

- Le castrum de Tours, étude architecturale du rempart du Bas-Empire (1983)

- Other references:

- ^ a b c "Enceinte romaine". Notice No. IA00071353, on the open heritage platform, Mérimée database, French Ministry of Culture. (in French). Archived from the original on 5 February 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Duby 1980, p. 110: D'Auguste au vie siècle : transformation dans le réseau des cités

- ^ a b c d Cherpitel, Thierry (2010). "De Caesarodunum à Tours – 2000 ans d'histoire urbaine" (PDF). National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) (in French). Archived from the original on 11 August 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Alföldi, André (1938). "La grande crise du monde romain au iiie siècle". L'Antiquité classique (in French). 7 (1): 7. doi:10.3406/antiq.1938.3063.

- ^ "À Tours, 2000 ans d'aménagement des bords de Loire". National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) (in French). 2011. Archived from the original on 9 December 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Duby 1980, pp. 409–410: Duby, Invasions du iiie siècle ; trésors monétaires et incendies

- ^ a b Duval, Paul-Marie (1989). "Travaux sur la Gaule (1946–1986) : Problèmes concernant les villes gallo-romaines du Bas-Empire". Publications de l'École Française de Rome (in French). 116 (1). École Française de Rome: 1049–1053. Archived from the original on 6 March 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ de la Sauvagère, Félix le Royer (1776). Recueil de dissertations ou Recherches historiques et critiques... (in French). Paris: Vve Duchesne. pp. 39–40.

- ^ Chalmel, Jean-Louis (1828). Histoire de la Touraine depuis la conquête des gaules par les Romains jusqu'à l'année 1790 (in French). Paris. p. 68.

- ^ Champoiseau, Noël (1831). Essai sur les ruines romaines qui existent encore à Tours et dans les environs (in French). Tours: Annales de la Société d'agriculture, de sciences, d'arts et de belles-lettres du département d'Indre-et-Loire. pp. 164–177.

- ^ Loizeau de Grandmaison, Charles (1859). "Notes sur la construction de l'enceinte antique de Tours". Mémoires de la Société archéologique de Touraine (in French) (11): 232–235.

- ^ Mabille, Émile (1862). "Notice sur les divisions territoriales et la topographie de l'ancienne province de Touraine (premier article)". Bibliothèque de l'École des Chartes (in French). 23: 331. doi:10.3406/bec.1862.445822.

- ^ Ranjard 1986, p. 8: L'histoire de Tours

- ^ Bedon, Chevallier & Pinon 1988, pp. 106–107: L'histoire de Tours

- ^ "Notice no IA00071382". Open heritage platform, Mérimée database, French Ministry of Culture. (in French). Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Notice no IA00071360". Open heritage platform, Mérimée database, French Ministry of Culture. (in French). Archived from the original on 4 February 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ a b Coulon 2006, pp. 21–22: Les enceintes urbaines

- ^ Neury, Patrick; Seigne, Jacques (2003). "Deux ponts antiques (?) à Tours". Revue archéologique du Centre de la France (in French). 42: 227–234. doi:10.3406/racf.2003.2940. Archived from the original on 5 March 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Seigne, Jacques; Kermorvant, Alain (2001). "Une porte (?) sur le rempart méridional du castrum de Tours". Revue archéologique du Centre de la France (in French). 40: 291–295. doi:10.3406/racf.2001.2883. Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ de Tours, Grégoire (1999). Histoire des Francs (in French). Vol. II. Paris: Les belles Lettres. p. 317. ISBN 2-251-34047-5.

- ^ Mabire la Caille, Claire (1985). "Contribution à l'étude du rempart des Arcis à tours". Bulletin de la Société archéologique de Touraine (in French). XLI: 136.

- ^ Croubois, Claude (1986). L'indre-et-Loire – La Touraine, des origines à nos jours. L’histoire par les documents (in French). Saint-Jean-d’Angely: Bordessoules. pp. 130–132. ISBN 2-903-50409-1.

- ^ Bedon, Chevallier & Pinon 1988, pp. 104–105: Les enceintes du Bas-Empire

- ^ "Le castrum du Bas-Empire". National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) (in French). Archived from the original on 24 September 2015. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Lefebvre 2008

- ^ Lorans, Élisabeth; Creissen, Thomas (2014). Marmoutier, un grand monastère ligérien (Antiquité – xixe siècle). Patrimoines en région Centre (in French). Orléans: French Ministry of Culture. p. 11. ISSN 2271-2895.

- ^ "Historique de la chapelle Saint-Libert". Société archéologique de Touraine (SAT) website (in French). Archived from the original on 25 September 2015. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Mabire la Caille, Claire (1988). Évolution topographique de la Cité de Tours des origines jusqu'au xviiie siècle (in French). Tours: Université François-Rabelais. p. 105.

- ^ Galinié, Henri (2004). "L'expression « terres noires », un concept d'attente" (PDF). Les petits cahiers d'Anatole (in French) (3).

- ^ Cammas, Cécilia; Borderie, Quentin; Desachy, Bruno; Augry, Stéphane. "L'approche géoarchéologique de l'urbain" (PDF). National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) (in French). p. 90. Archived from the original on 4 September 2014. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Historique de La Société Archéologique de Touraine". Société archéologique de Touraine (in French). Archived from the original on 5 July 2015. Retrieved 6 July 2015.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ "Notice no PA00098240". Open heritage platform, Mérimée database, French Ministry of Culture. (in French). Archived from the original on 30 October 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Auvray 1938

- ^ Galinié, Husi & Motteau 2014

- ^ Galinié 2007

- ^ "Atlas archéologique / Tours / Amphithéâtre antique". National Institute for Preventive Archaeological Research (INRAP) (in French). Archived from the original on 10 December 2017. Retrieved 3 November 2014.

{{cite web}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - ^ Wood 1983

- ^ Pietri 1983

- ^ a b Ranjard 1986, p. 53: Les quartiers nord-est

Bibliography[edit]

Books on the archaeology or history of Tours[edit]

- Audin, Pierre (2002). Tours à l'époque gallo-romaine (in French). Saint-Cyr-sur-Loire: Alan Sutton. ISBN 2-842-53748-3.

- Auvray, Henry (1938). "La Touraine gallo-romaine ; l'enceinte gallo-romaine". Bulletin de la Société Archéologique de Touraine (in French). XXVII: 179–204. Archived from the original on 8 January 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite journal}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Chevalier, Bernard (1985). Histoire de Tours. Univers de la France et des pays francophones (in French). Toulouse: Privat. ISBN 2-708-98224-9.

- Galinié, Henri; Randoin, Bernard (1979). Les archives du sol à Tours : survie et avenir de l'archéologie de la ville (in French). Tours: La Simarre.

- Galinié, Henri (2007). ours antique et médiéval. Lieux de vie, temps de la ville. 40 ans d'archéologie urbaine, 30e supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France (RACF), numéro spécial de la collection Recherches sur Tours (in French). Tours: FERACF. ISBN 978-2-91327-215-6.

- Galinié, Henri; Husi, Philippe; Motteau, James (2014). Des Thermes de l'Est de Caesarodunum au Château de Tours : le site 3 : 50e supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France (RACF). Recherches sur Tours 9 (in French). Tours: FERACF. ISBN 978-2-913-27236-1. Archived from the original on 15 May 2023. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Lefebvre, Bastien (2008). La formation d'un tissu urbain dans la Cité de Tours : du site de l'amphithéâtre antique au quartier canonial (5e-18e s.) (Thesis). Tours: Université François-Rabelais. Archived from the original on 7 October 2022. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite thesis}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Pietri, Luce (1983). La ville de Tours du ive au vie siècle. Naissance d'une cité chrétienne. Collection de l'École française de Rome, 69 (in French). Rome: École française de Rome. ISBN 2-728-30065-8. Archived from the original on 6 June 2024. Retrieved 2 July 2024.

{{cite book}}: CS1 maint: bot: original URL status unknown (link) - Provost, Michel (1988). Carte archéologique de la Gaule – l'Indre-et Loire-37 (in French). Paris: Académie des Sciences et Belles-Lettres. ISBN 2-87754-002-2.

- Ranjard, Robert (1986). La Touraine archéologique : guide du touriste en Indre-et-Loire (in French). Mayenne: Imprimerie de la Manutention. ISBN 2-855-54017-8.

- Riou, Samuel; Dufaÿ, Bruno (2016). Le site de la chapelle Saint-Libert dans la cité de Tours, Mémoire LXXIII de la Société archéologique de Touraine - 61e supplément à la Revue archéologique du centre de la France (in French). Tours: FERACF. ISBN 978-2-91327-247-7.

- Wood, Jason (1983). Le castrum de Tours, étude architecturale du rempart du Bas-Empire. Recherches sur Tours (in French). Vol. 2. Translated by Randoin, Bernard. Joué-lès-Tours: La Simarre.

Books devoted in whole or in part to architecture and town planning in the Roman Empire[edit]

- Bedon, Robert; Chevallier, Raymond; Pinon, Pierre (1988). Architecture et urbanisme en Gaule romaine : l'architecture et la ville. Les Hespérides (in French). Vol. 1. Errance. ISBN 2-903-44279-7.

- Coulon, Gérard (2006). Les Gallo-Romains. Civilisations et cultures (in French). Paris: Errance. ISBN 2-877-72331-3.

- Duby, Georges (1980). Histoire de la France urbaine, vol. 1 : La ville antique, des origines au ixe siècle (in French). Paris: Le Seuil. ISBN 2-020-05590-2.

External links[edit]

- Architectural resource: Mérimée