Russell Caves

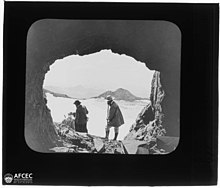

The Russell Caves are a group of seven caves that Count Henry Russell, a renowned Pyrenean mountaineer, had dug into the Vignemale massif in the French department of Hautes-Pyrénées, to serve as a shelter and holiday resort.

Exploring the Pyrenees since 1858, Count Russell spent many uncomfortable nights on the peaks he climbed. In the early 1880s, he decided to settle on a mountain and build a natural shelter for long stays at high altitude during the summer. He chose the Vignemale, the highest peak in the French Pyrenees. In 1881, a contractor from Gèdre drilled his first cave near the Cerbillona pass, the "Villa Russell", at an altitude of 3,205 meters. Six other caves were created up to 1893, at altitudes varying between 2,400 and 3,280 meters: the "Grotte des Guides", the "Grotte des Dames", the three "Bellevue caves" and the "Grotte Paradis".

In his caves, Henry Russell hosted sumptuous meals and welcomed numerous guests, all of whom praised the quality of his hospitality. By the end of the 19th century, the caves had become a must for Pyrenean visitors to the region, who left a testimonial in the visitors' book at the top of the Pique Longue. At the beginning of the 21st century, the retreat of the Ossoue glacier rendered some of these caves inaccessible.

Henry Russell, the Pyrenees and Vignemale[edit]

After climbing several Pyrenean peaks in the summer of 1858[1], Henry Russell turned his attention to exploring the range from 1861[2] onwards, becoming one of the leading figures in Pyrenean climbing.[3] That same year, on September 14, he climbed the Vignemale, the highest peak in the French Pyrenees, for the first time. From then on, he had a special relationship with this peak, making what is considered Europe's first major winter ascent on February 11, 1869, with guides Hippolyte and Henri Passet.[4]

A romantic, dreamy and contemplative character[5], he spent many nights on the summits, often uncomfortable and sometimes perilous, but which could also provide him with sublime moments, such as on August 26, 1880, at the summit of Vignemale.[6] Buried inside his lambskin rucksack, in a small ditch covered with stones, Henry Russell fell asleep only briefly due to the negative temperature, but he experienced one of the most beautiful moments of his life, amazed by the spectacle of the starry night as well as that of the sunrise.[6][7] This experience made him want to spend long periods of time at high altitude, and he realized that his age was making it difficult for him to keep up the mountain runs with a minimum of sleep and food. So he decided to settle on the Vignemale.[7]

The seven caves[edit]

The Russell villa (1881-1882)[edit]

For Henry Russell, "there is nothing uglier, more hideous and more repulsive than a house, in the midst of the eternal and sublime chaos of the mountains".[8] While he advocated living at high altitude, he did not accept construction, which he felt disfigured the mountain's wild appearance. Digging an artificial cave in the rock seemed the only option. His aim was to create a warm, dry shelter, without the need for a fire.[9]

In the summer of 1881, Henry Russell contacted Gèdre-based contractor Étienne Theil, who had built a shelter for him near Mont Perdu five years earlier.[10] He planned to cut a cave at an altitude of 3,205 meters on the flanks of the Cerbillona, near the Col de Cerbillona, at the top of the Ossoue glacier.[11] Once the contract had been signed, Theil and his workers began work in August, but progress was slow due to the hardness of the rock: after a few days, only a hole of around one cubic metre had been dug. Work was halted in early September, after a violent snowstorm had ransacked the workers' camp.[11] The following year, one of the workers, Justin Pontet, put forward the idea of setting up a forge near the site, to maintain the tools, which were rapidly becoming blunt. Work was completed on July 31, 1882, and the grotto was delivered to Count Russell the following day. With a capacity of 16 m3[11] , enclosed by a wall and a sheet metal door painted with minium[12], the grotto measures 3.1 meters long, 2.55 meters wide and just over 2 meters high. The cost of the work was 2,000 francs, including a 100-franc bonus for the workers.[11]

As soon as they received the cave, which was named "Villa Russell", its owner decided to spend three days there in the company of a young English mountaineer, Francis-Edward-Lister Swan, and three guides and porters, Henri Passet, Mathieu Haurine and Pierre Pujo.[11] On August 4, Jean Bazillac and Henri Brulle, completing a Pyrenean excursion to the Vignemale that had begun a few weeks earlier, made their way to Villa Russell, narrowly missing the Count and his guests, who had left the day before.[13] The following year, Henry Russell made several visits to his cave. The door, probably swept away by the winter weather, was finally found and reattached. Every evening, the Count climbed the Pique Longue to admire the sunset, in an unchanging ritual.[14]

In 1884, Henry Russell continued to refurbish his grotto. He installed the 35 kg stove given to him by Henri Vergez-Bellou, proprietor of the Hotel des Voyageurs in Gavarnie. For ten days in early August, more than 80 guests enjoyed the Count's hospitality, bringing him gifts of tea, Bordeaux wine, Madeira and Port. On August 11, the "Villa Russell", transformed into a chapel for the event, was blessed by priests from Lourdes, Héas and Saint-Savin, a consecration reported in regional newspapers.[15]

Grotte des Guides (1885) and Grotte des Dames (1886)[edit]

In 1885, as the "Villa Russell" was insufficient to accommodate both his friends and the guides and porters accompanying them, Henry Russell commissioned the same workers to dig a new grotto, known as the "Grotte des Guides", close to the first one. The work was completed on August 21.[16]

Russell further increased his accommodation capacity the following year with the construction of a third shelter, the "Grotte des Dames", built 4 meters above the previous ones, whose entrance was regularly blocked by the advancing Ossoue glacier.[16] He was very pleased with it: "my dear little grotte, that of the Ladies, the kindest, most gracious and warmest of all, the first to appear at the end of July, and the last to sink under the snow in October. This one is my greatest success: I'm very proud of it. Never in any weather have I seen a drop fall on it: and this time, in the flurries of snow and sleet that froze our fingers in front of the door, its atmosphere seemed oriental. If I said I found it almost too warm, in contrast to the air outside, I wouldn't be believed: so I'll just think it".[17]

Henry Russell sometimes organized lavish receptions. On August 6, 1888, his friends Roger de Monts and Jean Bazillac sent for a tent, beds, armchairs, books, lanterns, banners, Eskimo costumes and plenty of food. The tent was erected on the snow in front of the Russell villa, and given the name "Miranda villa". For three days, parties followed one another in an astonishing luxury at such an altitude.[18][19]

Shortly before his death, Russell entrusted the keys to his caves to another illustrious visitor, the poet Saint-John Perse.

The Bellevue caves and the Vignemale concession (1889-1990)[edit]

The rise of the Ossoue glacier makes access to the Cerbillona caves difficult. The Villa Russell and the Grotte des Guides were regularly buried under snow, so Henry Russell decided to build two new caves sheltered from the snow. He chose a site below the glacier, on the path leading to the hourquette d'Ossoue, at an altitude of 2,400 meters.[20] Offering superb views, they took the name "Bellevue caves" and became the Count's summer residence from 1889.[20] In 1890, a third, smaller cave without a door was built to store luggage and supplies.[21]

At the end of 1888, Henry Russell expressed his desire to become the owner of the Vignemale. He applied to the Barèges valley syndicate commission for a concession that would give him symbolic ownership of all the snow and rock above 2,300 meters, for a total of 200 hectares around the massif. On December 13, he also sent a letter to the prefect of the Hautes-Pyrénées, Charles Colomb.[22][23] Count Russell himself drew up a plan of the area concerned, within a line that runs from the summit of the Pique Longue to the hourquette d'Ossoue via the Petit Vignemale, then south-eastwards through the Bellevue caves to the Montferrat ridge, then back to the Pique Longue along the border.[22] Meeting on February 25, 1889, the syndicate commission, considering that this proposal could be beneficial for the development of tourism in the region, unanimously decided to accept Count Russell's offer. With the Prefect's approval, it granted him the concession of the massif for a period of 99 years, in exchange for the payment of a symbolic franc each year. It also authorized the Count to make any improvements he deemed necessary, and to establish trails or paths to facilitate access. The lease was officially granted on the following October 10.[22]

Paradis grotto (1892-1893)[edit]

Despite the satisfaction of owning the massif, Henry Russell regretted the low altitude of his last caves. So he came up with the idea of a seventh and final shelter. In the summer of 1892, he began construction of the "Paradise Cave" at an altitude of 3,280 meters, 18 meters below the summit of Pique Longue. Due to the hardness of the rock and the storms that regularly hit the summit, the work was extremely difficult. In six weeks, the workers could only extract 8 m3 of rock. The work was resumed in the summer of 1893, this time using dynamite. Henry Russell was the first private individual in France to be authorized to use this type of explosive, reserved for mines and quarries or for military use.[24]

In twenty days, the cave's capacity was increased to 16 m3. Like the first Cerbillona caves, the new shelter was blessed by the parish priest of Gèdre, Pascal Carrère.[24] In the years that followed, Henry Russell was a regular visitor to his caves, and was responsible for their upkeep. In 1894, he made his twenty-fifth ascent of the Vignemale, celebrating what he called his "silver wedding" with the summit, in the company of his friend Bertrand de Lassus and guides Henri Passet, Mathieu Haurine and François Bernat-Salles.[25] He bid farewell to the Vignemale in 1904, after making his thirty-third and final ascent of the summit on August 8, 1904. During this final seventeen-day stay on his beloved mountain, he observed the spectacular melting of the Ossoue glacier and had a small, three-meter-high square tower built to rectify the summit's altitude by raising it above 3,300 meters. His first two attempts, in previous years, had not withstood the elements.[26][27]

Receptions in the caves[edit]

Henry Russell, who himself had an enormous appetite and was described as "a voluptuous friend of good food" by mountain writer Henry Spont[28], ensured that his guests lacked for nothing during their stay in the Vignemale caves. Everyone agreed on the quality of his welcome, as evidenced by the many messages left in the visitors' book at the top of the Pique Longue.[29] To welcome his guests, the Count systematically provides hot beverages such as soup, tea, chocolate, coffee or punch-brûlant, as well as numerous canned solid foods. His guides regularly made the journey to the villages below to provide supplies.[29] One of them, Mathieu Haurine, became the Count's regular cook during these stays.[30]

At Vignemale, Henry Russell organized "some feasts worthy of Lucullus", in the words of his biographer Monique Dollin du Fresnel. Among the dishes he offers his guests are fricandeau à l'oseille, bœuf à la mode, veal, mutton and Scottish herring, all washed down with a few bottles of wine. These meals ended "in the aromatic smoke of Oriental tobaccos"[29], with the Count taking up the habit of smoking a cigar after dinner, as he regularly did at the top of the mountains he had just climbed, as the climax of the ascent.[31] Henri Brulle, one of the Count's most frequent guests, writes in his memoirs of the value of these agapes: "Meticulous preparations were made for stays in his caves. The question of supplies was a serious one, for the troglodyte squire had a big appetite and loved to entertain. And what a kitchen he had! [...] Invitations were issued in series, combined with impeccable tact, making for charming and unforgettable get-togethers. Who, moreover, among us, the privileged, would not affirm that those nights were the best of his life[32]?"

Henry Russell himself evokes the splendor of these gastronomic meals at high altitude in an article entitled "L'Avenir du Vignemale", published in the Gazette de Cauterets on August 5, 1886. In it, he humorously imagines the discovery of the caves a thousand years later by a geologist and his students[33]:

"The Professor, in white tie, eyes upwards, in a long black frock coat (if one is still wearing one), and in a masterly tone: "in these places everything speaks to us of the sea: everything recalls it. There was a very stormy gulf here: these caves were dug by the sea: see the traces of the waves. Then, as the sea level dropped, the caves left on the shore were inhabited by dreadful troglodytes (perhaps by dreadful brigands...), who, as you can see, lived on the edge of the ocean, since there are pieces of petrified lobster, traces of herring, a few traces of sardine everywhere" [...] Excuse me, sir, but here's a trout bone, a fish that can only live in fresh water!!!! [...] Second pupil: "Sir, here are some quail remains and chicken bones!!!"[34]

The caves since Russell's death[edit]

After Count Russell's death, a bronze plaque by Bordeaux sculptor Gaston Leroux was affixed above the entrance to the Paradis Caves in 1913.[35] The Russell Caves continue to be visited by many climbers who seek shelter here.[36] However, since the beginning of the 21st century, the rapid melting of the Ossoue glacier has prevented level access to the Cerbillona caves. In 2017, glaciologist Pierre René uncovered one of the gates that closed the entrance, which had disappeared under the glacier at the end of the 19th century, when it was still growing in size.[37]

In 2021, an association, in partnership with the Parc National des Pyrénées, restored the sundial that Count Russell had placed on the side of one of Bellevue's caves.[38]

In 1987, cartoonist Jean-Claude Pertuzé climbed to the summit of the Vignemale to write and draw, in twenty-four hours, Le jour du Vignemale, a portfolio of 32 plates published by Editions Loubatières. In 2011, a new colorized version was published under the title Vignemale, l'autre jour.[39]

See also[edit]

References[edit]

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 79-89)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 157)

- ^ Lasserre-Vergne (2021, p. 77-83)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 181)

- ^ Lasserre-Vergne (2021, p. 25-29)

- ^ a b Lasserre-Vergne (2021, p. 61-65)

- ^ a b Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 202-203)

- ^ Russell, Henry. Histoire et vicissitudes de mes grottes du Vignemale (in French). Imprimerie Vignancour. p. 7.

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 203-204)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 187-189)

- ^ a b c d e Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 204-206)

- ^ Lasserre-Vergne (2021, p. 91)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 207)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 207-209)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 209-212)

- ^ a b Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 213-214)

- ^ Russell, Henry. "Ma vingtième ascension au Vignemale". Revue des Pyrénées et de la France méridionale (in French). 3: 273–280.

- ^ Escudier, Jean (1976). "La villa Miranda". Pyrénées (in French) (108): 366–371.

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 222)

- ^ a b Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 218-219)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 232)

- ^ a b c Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 228-230)

- ^ Cadart, Charles (1943). La Concession Russell du Vignemale (in French). Imprimerie Bière. p. 24.

- ^ a b Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 230-231)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 231-233)

- ^ Lasserre-Vergne (2021, p. 97-98)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 352)

- ^ Spont, Henry (1914). Les Pyrénées, les stations pyrénéennes, la vie en haute montagne (in French). Perrin.

- ^ a b c Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 210-215)

- ^ Lasserre-Vergne (2021, p. 67)

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 160-165)

- ^ Brulle, Henri (2006). Ascensions : Alpes, Pyrénées et autres lieux (in French). PyréMonde. p. 199. ISBN 2-84618-265-5.

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 214-215)

- ^ Russell, Henry. "L'Avenir du Vignemale". La Gazette de Cauterets (in French).

- ^ Dollin du Fresnel (2009, p. 388-395)

- ^ "Grotte Paradis". pyrénées-refuges.com.

- ^ Barréjot, Andy (2017). "Vignemale: la fonte du glacier révèle des secrets plus que centenaires". La Dépêche du Midi (in French).

- ^ Barréjot, Andy (2021). "Vignemale : Les grottes de Russell retrouvent leur cadran". La Nouvelle République des Pyrénées.

- ^ "Décès de Jean-Claude Pertuzé, auteur de BD et illustrateur". ActuaLitté (in French). 2020.

Bibliography[edit]

- Beraldi, Henri (1904). Cent ans aux Pyrénées (in French). Réédition par Les Amis du Livre Pyrénéen.

- Dollin du Fresnel, Monique (2009). Henry Russell (1834-1909) : Une vie pour les Pyrénées (in French). Éditions Sud Ouest. ISBN 978-2-87901-924-6.

- Lasserre-Vergne, Anne (2021). Henry Russell : montagnard des Pyrénées. Petite Histoire (in French). Cairn. ISBN 978-2-35068-984-5.

- Pérès, Marcel (2009). Henry Russell et ses Grottes : Le Fou du Vignemale. L'empreinte du temps (in French). Presses universitaires de Grenoble. ISBN 9782706115226.

- Pertuzé, Jean-Claude (1987). Le Jour du Vignemale (in French). Loubatières.